Keywords

Apremilast, Plaque psoriasis, Phosphodiesterase 4, Psoriatic arthritis

Key points

- •

Apremilast is the first small molecule phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

- •

Apremilast, in contrast to biologics, is not injectable, and its label does not require monitoring or screening for tuberculosis.

- •

Apremilast is the first selective PDE4 inhibitor that is US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis.

- •

Apremilast has a favorable safety profile so far, and it can be used in patients with comorbidities that preclude use of other systemic medications.

Introduction

Apremilast, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014, is the first phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved to treat psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Biologics have revolutionized the treatment of psoriasis. They are more effective and safer than the oral options previously available. Biologics may not be the preferred systemic psoriasis treatment for every patient, however, because side effects include injection site reactions, upper respiratory tract infections, infusion reactions, and risk of reactivation of tuberculosis. They may also be limited by their high cost as well as their need to be injected as the route of administration. Nevertheless, patient adherence to biologics used in psoriasis may be as low as 33%. Some patients prefer an oral medication; 1 study found 93% of patients chose oral medication administration over injectable agents, assuming equal drug efficacy.

Apremilast may be a good choice for patients who prefer a relatively safe oral treatment, and for patients in whom other therapies are contraindicated or become ineffective, such as those who develop antidrug antibodies against certain biologics. It is taken at home and offers the potential for better adherence for patients who may not be able to readily return to clinic for scheduled injections. It is an acceptable therapy for patients with certain medical comorbidities, especially renal, hepatic, or hematologic, where some biologics or traditional systemic psoriasis therapies may be contraindicated. It is also an acceptable therapy for patients with compromised immunity, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In addition, apremilast can be safely combined with several systemic psoriasis treatments for greater efficacy.

Apremilast is being tested for treatment of other diseases. Currently, there are clinical trials testing apremilast in patients affected by cutaneous lupus, lichen planus, cutaneous sarcoidosis, atopic dermatitis, ankylosing spondylitis, prostatitis, vulvodynia, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Behcet disease, and rosacea, because these diseases are thought to be affected to some degree by the same pathways apremilast acts on.

Mechanism of action

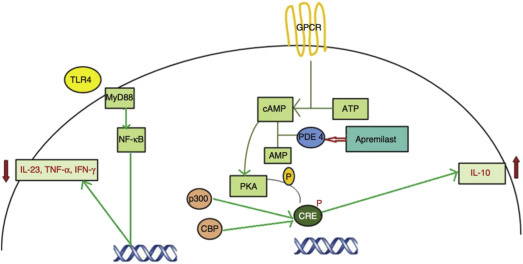

Apremilast is a selective inhibitor of PDE4. Phosphodiesterases facilitate the breakdown of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP). Thus, by blocking PDE4, intracellular cAMP levels increase, reducing proinflammatory mediators, such as interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-17, and IL-23. Increasing cAMP levels also increase anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 ( Fig. 7.1 ). Specifically, the increased intracellular accumulation of cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphorylates the cAMP-response element binding protein, which suppresses the transcription of numerous proinflammatory cytokines, exerting an overall anti-inflammatory effect. The increased cAMP downregulates myeloid dendritic cells as well as T helper 1 and T helper 2 immune responses. This downregulation decreases immune cell infiltration in the epidermis and dermis of psoriatic lesions and causes a reduction in gene expression of numerous cytokines (IL-12/IL-23p40, IL-22, IL-8, β-defensin 4, myxovirus resistance protein 1, IL-17A, and IL-23p19). The systemic effects of PDE4 inhibition may lead to some of the side effects seen with apremilast, such as weight loss. In contrast to TNF-α inhibitors, such as infliximab or adalimumab, which bind directly to TNF-α, PDE4 inhibitors inhibit TNF-α production at the level of gene expression and do not completely suppress TNF-α levels; this leads to a decrease of proinflammatory mediators, but not complete inhibition.

Efficacy

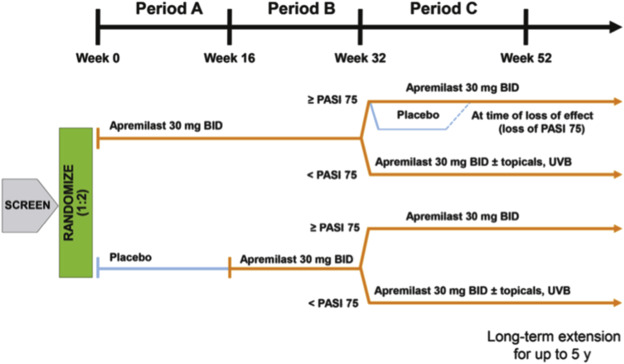

The efficacy of apremilast on plaque psoriasis has been tested in 2 separate phase 3 trials. ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 included 1257 patients 18 years of age or older with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Moderate-to-severe plaque disease was defined by body surface area involvement of 10% or greater; static Physicians’ Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 3 or greater (moderate or severe disease); Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score 12 or greater; and candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Both studies assessed the proportion of patients who achieved PASI-75 at week 16 and those who achieved an sPGA score of either 0 (cleared disease) or 1 (minimal disease) at week 16. In the ESTEEM 1 trial, a total of 844 patients were studied over 52 weeks, divided into 3 periods. Period A looked at apremilast 30 mg twice daily versus placebo from 0 to 16 weeks; patients were randomized 2:1, apremilast:placebo. Period B ranged from week 16 to 32 and replaced the initial placebo with apremilast. Period C rerandomized patients who started with apremilast initially and showed a PASI-75 or greater at week 32 to placebo or apremilast ( Fig. 7.2 ). At 16 weeks, more patients who received apremilast achieved a PASI-75 compared with placebo (33.1% vs 5.3%, respectively; P <.001). Furthermore, more patients who received apremilast (21.7%) achieved an sPGA score of 0 or 1 compared with placebo (3.9%). Achieved response rates were maintained well at week 32. Long-term efficacy was reported as the percentage of patients who were still on drug. Of the 844 original patients randomized, 314 patients that had received at least 1 dose of apremilast discontinued the study by week 52, with 124 patients citing “lack of efficacy” as the reason for discontinuing. When determining long-term efficacy rates, those with PASI-75 out of the only the remaining patients in the study were used in calculating reported PASI-75 rates, which yielded a higher efficacy rate than would have been reported if all patients who started on drug were included in the denominator. In ESTEEM 1, of all the patients exposed to apremilast at any period of the study, including those who discontinued the study, 18.7% were at PASI-75 at week 52.

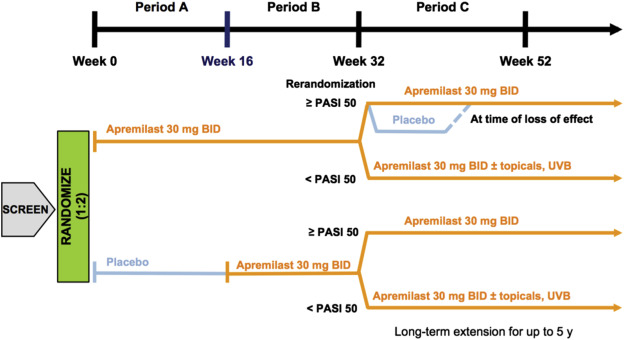

In the ESTEEM 2 trial, a total of 411 patients were studied. Patients were initially randomized 2:1, apremilast:placebo, and at week 16, all patients were switched to apremilast. At week 32, patients were evaluated for PASI-50 or greater, and patients who met these criteria were randomized 1:1 to receive apremilast or placebo ( Fig. 7.3 ). At week 16, more patients who received apremilast achieved a PASI-75 compared with placebo (28.8% vs 5.8%). In addition, more patients who received apremilast achieved an sPGA of clear or almost clear compared with placebo (20.4% vs 4.4%, respectively; P <.001). The response was sustained over 52 weeks without significant adverse effects ( Table 7.1 ). As with ESTEEM 1, the long-term results from the ESTEEM 2 study were reported based only on the subjects remaining in the study. Of the original 411 randomized patients, 115 that had received at least 1 dose of the drug discontinued the study before 1 year. Of the 115 patients that discontinued, 47 cited “lack of efficacy” as the reason.

| Clinical Response | ESTEEM-1 | ESTEEM-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo, N (%) (N = 282) | Apremilast 30 mg Twice Daily, N (%) (N = 562) | Placebo, N (%) (N = 137) | Apremilast 30 mg Twice Daily, N (%) (N = 274) | |

| PASI-75 | 15 (5.3) | 186 (33.1) | 8 (5.8) | 79 (28.8) |

| sPGA of clear or almost clear | 11 (3.9) | 122 (21.7) | 6 (4.4) | 56 (20.4) |

Apremilast has been retrospectively studied in combination with multiple systemic psoriasis treatments, including narrowband (NB)-UV-B, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, or ustekinumab. Efficacy was greater with apremilast combination therapy than with either treatment modality alone. It was slightly less effective than etanercept 50 mg in clearing psoriasis, as measured by PASI-75 response at 16 weeks. In an ongoing phase III trial comparing apremilast to etanercept and placebo, 48% of etanercept patients and 40% of apremilast patients achieved PASI-75 at week 16. The higher efficacy rate in this study (40%) than in the ESTEEM trials may be due to a less severe population because these patients were biologically naïve (whereas in ESTEEM, many of the subjects had previously failed biological treatment). A single case report combining apremilast and adalimumab resulted in an almost clearing of severe, biologic-resistant plaque psoriasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree