Appendage Tumors and Hamartomas of the Skin: Introduction

|

Classification and Pathogenesis

Appendageal tumors of the skin comprise a wide spectrum of benign and malignant neoplasms that exhibit morphological differentiation toward one or more adnexal structures in normal skin. The classification and diagnosis of appendageal tumors is challenging due to the wide variety of tumor types, complicated nomenclature, and numerous classification systems that categorize these neoplasms.1–8 Traditionally, cutaneous adnexal tumors are classified into four groups according to differentiation toward follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, and eccrine structures. These adnexal tumors can be further classified by a gradient of decreasing differentiation into three groups: hyperplasias and hamartomas, benign neoplasms, and malignant neoplasms (Table 119-1). This classification is similar to the approach of the World Health Organization International Histological Classification of tumor monographs.4 The hyperplasias are characterized by an increased number of normal cells in a normal arrangement. Hamartomas are described as an abnormal arrangement of normal tissue. Benign neoplasms lack the potential to metastasize, whereas malignant tumors have the ability to cause local destruction and to metastasize to lymph nodes and viscera.

Sebaceous | Apocrine | Eccrine | Follicular |

|---|---|---|---|

Hamartomas, Hyperplasias, and Cysts | |||

|

|

|

|

Benign Neoplasms | |||

|

|

|

|

Malignant Neoplasms | |||

|

|

|

|

While adnexal tumors are classified based on differentiation, often a tumor is not easily classified into one group because the lesion exhibits histologic features of two or more adnexal cell lines. Since adnexal tumors originate from pluripotent stem cells in the epidermis and its appendages, neoplastic cells may aberrantly express one or more lines of appendageal differentiation. The ultimate histologic characteristics of a tumor are related to the activation of molecular pathways responsible for forming the normal mature adnexal structure, in conjunction with tumor genetics, local vascularity, and microenvironment.4

During embryogenesis, the eccrine apparatus develops separately from the folliculosebaceous-apocrine apparatus. Eccrine glands develop directly from the embryonic epidermis during the third to fifth months of fetal development. Hair follicles also arise directly from the epidermis during the third to fourth months of fetal life. Follicular development differs from eccrine development because mesenchymal cells, which serve as precursors of the follicular papilla, descend into the dermis with the developing epidermal elements. Sebaceous and apocrine glands and ducts begin as secondary structures from the bulges along the hair follicle. Clinically, as predicted by embryogenesis, follicular, sebaceous, and apocrine tumors coincide in the same individuals, whereas eccrine tumors are unrelated.8

Cytogenetics and molecular studies have further elucidated the pathogenesis of certain adnexal tumors. Mutations in p53 have been detected in some adnexal tumors, suggesting an etiologic role for ultraviolet light.9 Germ-line mutations have been reported in various genodermatoses, suggesting a role for these genes in the pathogenesis of certain adnexal tumors. For instance, mutations in the patched (PTCH) genes have been demonstrated in follicular tumors in patients with the basal cell nevus syndrome.10 Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN have been identified in patients with Cowden’s syndrome.11 Microsatellite instability and mutations in MSH2, MLH1, and MSH6 mismatch repair genes have been detected in patients with Muir–Torre syndrome.12 Technologies such as cDNA microarrays, microRNA microarrays, and proteomic studies may lead to the elucidation of additional molecular markers useful in classifying these neoplasms.

Differential Diagnosis

Clinically, appendageal tumors are indistinctive, and often present as flesh-colored papules or nodules. Lesions may be solitary or multiple. The anatomic distribution of these lesions corresponds to the normal location of the adnexal structure from which the neoplasms originates. When patients present with multiple lesions, a characteristic anatomic distribution, autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and association with visceral abnormalities may be observed. Often, appendageal tumors serve as a marker for genetic syndromes. While most lesions are benign, a malignant counterpart exists for most tumors, and it is often associated with a poor outcome.

The most important tool for diagnosing and classifying appendageal tumors is histopathology. The histopathology of the adnexal tumor can be interpreted by comparing its microscopic features to the histology of normal cutaneous appendages. Follicular tumors show a range of morphologic features that recapitulate specific portions of normal hair and the hair follicle such as the infundibulum, isthmus, stem, and bulb. The finding of matrical cells reflects differentiation toward follicular bulbs. Trichohyalin granules and blue–gray corneocytes indicate differentiation toward the inner root sheath. Differentiation toward the outer root sheath is manifested by the presence of either clear columnar cells aligned in a palisade at the bulb, subtly cornified cells with pink cytoplasm at the stem, or fully cornified cells with red cytoplasm, which corresponds to trichilemmal keratinization at the level of the isthmus. Sebaceous tumors reveal areas with sebocytes distinguished by a vacuolated cytoplasm, scalloped nuclei, and tubular structures. Ductal differentiation characterizes apocrine and eccrine tumors. Features of apocrine glands such as decapitation secretion are seen in ductal structures of apocrine neoplasms, whereas a flattened ductal epithelium distinguishes eccrine neoplasms.4

Immunohistochemical analysis has traditionally been of little value in definitively diagnosing adnexal tumors given the significant overlap of immunohistochemical features between apocrine tumors with ductal differentiation and certain visceral malignancies.

Determination of whether an appendageal neoplasm is benign or malignant requires assessment of architectural and cytomorphologic characteristics. Great care is necessary when applying traditional morphologic criteria of malignancy such as asymmetry, poor circumscription, and presence of epithelial aggregations with prominent atypia and mitotic activity. Some malignant aggressive adnexal neoplasms have deceptively bland microscopic appearance. Furthermore, there are certain neoplasms whose malignant potential is not always predictable on histologic grounds alone.

Treatment

A diagnostic biopsy of a suspicious lesion yielding a correct diagnosis is the initial step in appropriate management of patients with appendageal skin tumors. A number of tumor-related and patient-related factors influence the choice of treatment. Tumor-related factors include the type, size, and anatomic location. Patient-related factors include life expectancy, comorbid conditions, and cosmetic concerns.

Specific treatment of benign appendageal tumors is sometimes unnecessary. In some cases, removal of the tumor is indicated for cosmetic reasons only. The treatment of choice for the majority of benign appendageal tumors is surgical excision. A variety of superficial ablative techniques such as electrodessication and curettage and cryotherapy have proven to be effective in selected patients. A number of other alternative treatment options, including the use of systemic retinoids, lasers, and photodynamic therapy have also been advocated for use in some cases; however, most do not have sufficient data for universal application.

Treatment of malignant appendageal tumors aims mainly at eradication of the cancer, preservation or restoration of normal function, and cosmesis. High-risk patients with tumors known to recur or metastasize most frequently require wide local excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, and/or radiotherapy. Notably, sentinel lymph node biopsy is sometimes valuable in staging of patients with eccrine and apocrine carcinomas.

Sebaceous Neoplasms

Sebaceous tumors consist of a wide spectrum of neoplasms from hamartomas, hyperplasias, and benign lesions to highly aggressive malignant tumors. Sebaceous neoplasms, with the exception of sebaceous hyperplasia, are relatively rare compared to the other appendageal tumors. Sebaceous lesions are associated with two systemic syndromes: Muir–Torre syndrome and the epidermal nevus syndrome.

Sebaceous glands develop from the hair sheath, and are located near hair follicles, apocrine ducts, and arrector pili muscles. Sebaceous glands are located in all hair bearing regions of the body, and are most abundant in the head and neck region.13 Ectopic sebaceous glands are common and considered a normal variant. Fordyce spots are located on the vermilion border of the lip and labia minora, Tysons glands on the prepuce and mucosa of the penis, and Montgomery tubercles on the female areola.14

Terminology regarding sebaceous neoplasms remains controversial. The term sebaceous adenoma has been applied to superficial benign sebaceous neoplasms with predominantly mature sebocytes, whereas sebaceous epithelioma and sebaceoma have been used to describe lesions consisting of primarily germinative seboblasts. Others have used the term sebaceoma to describe benign sebaceous proliferations deep in the dermis as opposed to the more superficial sebaceous adenoma.15 In this chapter, the term sebaceous adenoma is used to encompass superficial and deep sebaceous proliferations with varying degrees of sebocyte maturity.

Nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, described in 1895, is a benign hamartoma with epidermal, follicular, and apocrine elements.16 It occurs in 3/1,000 neonates.14

Nevus sebaceous is postulated to develop due to genetic mosaicism in stem cells that expand in the lines of Blaschko. The human papilloma virus (HPV) has been detected in nevus sebaceous tissue, with evidence of viral integration of HPV DNA into genomic DNA.17 These results suggest that maternal transmission of HPV DNA to fetal ectodermal cells could result in epigenomic mosaicism and subsequent cutaneous changes. In familial cases, a paradominant mode of transmission has been suggested.18 Loss of heterozygosity of the patched gene has also been demonstrated in some nevus sebaceous lesions.19

Nevus sebaceous presents as a well-demarcated, yellow–orange, alopecic, verrucous plaque that ranges in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. It most commonly occurs on the scalp (59.3%), but can also occur on the face (32.6%), preauricular area (3.8%), and neck (3.2%).20 It is usually solitary and linear or crescentic, and is distributed in the lines of Blaschko.21

Mehregan and Pinkus described three stages in the clinical and histological evolution of a nevus sebaceous.22 The lesion is slightly raised and barely discernible at birth. The initial stage is characterized by papillomatous epithelial hyperplasia and underdeveloped hair follicles. The second stage commences at puberty and is associated with remarkable sebaceous gland development, epidermal verrucous hyperplasia, and the maturation of apocrine glands. Clinically, this correlates with progressive thickening and development of a pebbly verrucous surface. The final stage involves the development of benign and malignant neoplasms within the nevus sebaceous.

Several neoplasms have been described arising within a nevus sebaceous.20,23 The most common benign neoplasm to occur in nevus sebaceous is trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Trichoblastomas, seen in about 5% of nevus sebaceous, presents with new pigmented papules or nodules. The development of basal cell carcinoma is seen in less than 1% of lesions. Other tumors reported to develop in nevus sebaceous include nodular hidradenoma, syringoma, trichilemmoma, proliferating trichilemmal cyst, squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, apocrine carcinoma, and eccrine poroma.24

In early nevus sebaceous, the epidermis is acanthotic and papillomatous. The sebaceous gland is underdeveloped and decreased in number, leading to difficult diagnosis. The presence of immature hair follicles that resemble the embryonic stage of hair follicles can aid diagnosis in early lesions. At puberty, the epidermis is papillomatous, verrucous, and hyperplastic. Abundant sebaceous glands and vellus hairs are noted in the superficial dermis. Apocrine glands are seen in two-thirds of patients at puberty.22,25

The risk of malignancy in nevus sebaceous is quite low, with the incidence of basal cell carcinoma at 1%. The risk of malignancy increases with age with the majority of studies indicating that children are unlikely to develop malignant tumors.23

Nevus sebaceous is associated with the linear nevus sebaceous syndrome, a subset of the epidermal nevus syndrome. Also known as Schimmelpenning Syndrome, this syndrome is characterized by linear nevus sebaceous, mental retardation, seizures, ophthalmic, skeletal, cardiovascular, and urologic defects. Appropriate work-up in these patients includes electroencephalogram, cerebral computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, skeletal survey, analysis of renal and liver function, and calcium and phosphate levels.26

Treatment is primarily cosmetic, and surgical excision to adipose or galea is the treatment of choice. Given the low risk of malignancy, many advocate that observation until adolescence is warranted as opposed to early excision. For facial lesions, consideration should be given to excision during childhood when scarring is minimal. Other treatment modalities including photodynamic therapy, carbon dioxide laser resurfacing, and dermabrasion have been advocated. However, since they fail to completely eradicate the lesion, there is a risk of recurrence or development of new tumors.27–29

Sebaceous hyperplasia, a benign enlargement of the sebaceous lobule around a follicular infundibulum, is a common lesion especially in patients with significant sun exposure. The age of onset is 40, with males more commonly affected than females. Prevalence increases with time.21

The cause of sebaceous hyperplasia is unknown. Although it is seen in individuals with extensive sun exposure, studies do not show an association with solar elastosis or skin type.30 Sebaceous hyperplasia is associated with renal transplantation and chronic immunosuppression with cyclosporine.31,32 Ten percent to 15% of patients on cyclosporine develop sebaceous hyperplasia, which can occur several years after starting the medication, and may affect ectopic locations such as the oral mucosa. Other associations include chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, corticosteroids, Muir–Torre syndrome, pachydermoperiostosis, and X-chromosomal ectodermal dysplasia.33

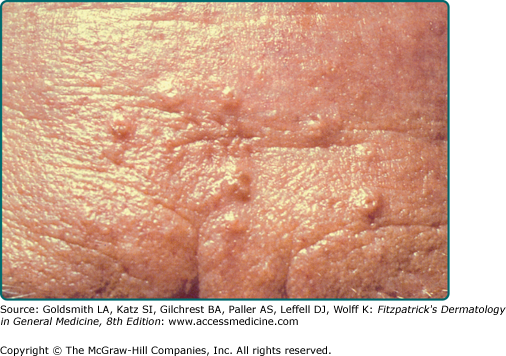

Sebaceous hyperplasia presents as solitary or multiple small ∼3 mm yellow or flesh-colored telangiectatic papules with a central dell on the central face (Fig. 119-1A).21 Nonfacial locations such as the neck, chest, areola, vulva, and penis have also been described.34–36 Atypical presentations include giant or linear lesions, diffuse growths, and juxtaclavicular beaded lines.21,36 Some reports have described sebaceous hyperplasia developing over neurofibromas, melanocytic nevi, verruca vulgaris, and acrochordons.37 Premature or functional familial sebaceous hyperplasia occurs in adolescence and is typified by thick diffuse plaque-like lesions on the face, chest, and upper back.38 Clinically, sebaceous hyperplasia can resemble basal cell carcinoma, and biopsy is performed to rule out malignancy. Dermoscopy can facilitate diagnosis of sebaceous hyperplasia, and reveals a yellow papule with telangiectasias and a central crater.39

Sebaceous hyperplasia reveals large mature sebaceous lobules clustered around discrete, often dilated, infundibula located in the upper dermis.

The most common variant, the senile variant, is associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer in renal transplant patients.31 Sebaceous hyperplasia may be associated with Muir–Torre syndrome, although it does not serve as a marker for the syndrome, given its high prevalence in the population.40

Treatment of sebaceous hyperplasia is for cosmetic purposes. The following destructive modalities have been shown to be effective: excision, cryotherapy, electrodessication and curettage, electrocautery, photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid, and laser therapy with the argon, carbon dioxide, pulse dye, and 1,450 nm diode lasers. These can be associated with scarring, hypopigmention, bleeding, and recurrence.21,33 Isotretinoin has been shown to be effective, but lesions recur rapidly after the medication is continued.33

Sebaceous adenomas are rare benign tumors that typically present on the head and neck of elderly individuals.41 These tumors serve as a marker for Muir–Torre syndrome.40

As a marker of the Muir–Torre syndrome, these lesions demonstrate microsatellite instability and mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2, MLH1, and MSH6.12

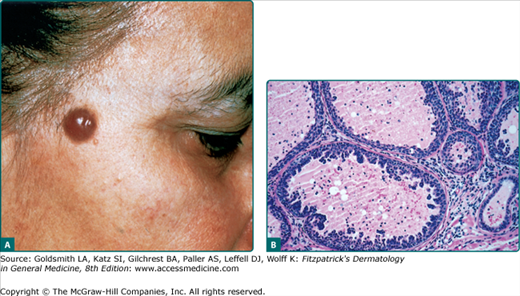

A sebaceous adenoma usually presents as a smooth, well-circumscribed, slow-growing pink, flesh-colored, or yellow papule or nodule measuring less than 0.5 cm (Fig. 119-2A). The most common location is the head (70%), followed by the neck, trunk, and legs (30%). Lesions may bleed, ulcerate, and cause pain.42

Sebaceous adenomas reveal multiple well-circumscribed sebaceous lobules. Each lobule has two cell populations: peripheral basaloid germinative cells and mature lipid-filled vacuolated sebocytes in the center of the lobule. Usually, mature sebocytes outnumber the undifferentiated germinative cells (Fig. 119-2B). These lesions lack atypia, necrosis, and invasive growth, which differentiate them from sebaceous carcinoma. Mitoses can be seen in the germinative layers, and is not necessarily indicative of malignancy.4

Sebaceous adenomas are the most common neoplasm associated with Muir–Torre syndrome, occurring in 68% of patients. In these patients, lesions tend to occur on the trunk. There are no reports of metastases from these neoplasms.26

The treatment of choice is complete surgical excision. Persistence or recurrences are common. Mohs micrographic surgery may be beneficial for conservation of the nipple.21 Cryosurgery may be useful in the treatment of some patients.

Work-up for Muir–Torre syndrome should be initiated in patients with a sebaceous adenoma.

Sebaceous carcinoma is a rare aggressive neoplasm that typically presents on the eyelids of elderly individuals. It represents 1%–5.5% of all eyelid malignancies.43 The mean age of onset is 63 years, although it has been reported in children.44 While women and Asians were previously thought to have a higher incidence, an analysis of 1,349 cases in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database revealed a slight male predisposition and no Asian predominance.45 Other risk factors include previous irradiation, genetic predisposition for the Muir–Torre syndrome, and immunosuppression with renal transplantation or HIV.45

Most sebaceous carcinomas develop de novo, although they can also originate from benign sebaceous neoplasms. These tumors are also associated with the Muir–Torre syndrome and may demonstrate microsatellite instability in DNA mismatch repair genes.26

The most common clinical presentation is a painless, slowly enlarging, subcutaneous nodule.45 Other clinical presentations mimic chalazion, blepharoconjunctivitis, and basal cell carcinoma, leading to delays in diagnosis.

The most common location is the eyelid, with upper eyelid involvement more frequent than lower eyelid involvement.46 These tumors develop from the meibomian glands and glands of Zeis. Extraocular lesions present as firm, yellow, ulcerated, or bleeding nodules on the head and neck, and less commonly, on the trunk, feet, external genitals, and oral mucosa.

Sebaceous carcinoma is characterized by asymmetric, irregular sebaceous lobules centered in the dermis. Lesions are classified as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated, based on varying degrees of differentiation. Four patterns are recognized: lobular, comedocarcinoma, papillary, and mixed. Tumor cells show remarkable variation in nuclear shape and size, pleomorphism, hyperchromatism, and mitotic activity. Tumors may extend into the subcutaneous fat or muscle.21

Sebaceous carcinoma is highly aggressive, with a potential for nodal and distant metastases. Recurrence after excision is common. Ocular lesions have a recurrence rate of 11%–30% with distant metastases occurring in up to 25% of patients. Extraocular sebaceous carcinoma is associated with a 29% recurrence rate, and 21% metastatic rate.45 It was previously believed that ocular tumors were more aggressive than extraocular tumors, but this has been challenged, with many reports of metastatic extraocular disease.47,48 The most common site of metastasis is regional lymph nodes, but there are reports of metastases extending to the liver, small bowel, urinary tract, lung, and brain.49

Mortality rates range from 9% to 50%.21 Overall 5-year survival rates for ocular versus extraocular disease is 75.2% and 68%, respectively.45 Negative prognostic signs include upper and lower lid involvement, lymphovascular invasion, multicentric disease, size larger than 1 cm, poorly differentiated tumors, and pagetoid spread.45

The standard treatment has been wide local excision with 5–6 mm margins. However, this has been associated with high recurrence rates of 36% and a 5-year mortality rate of 18%.21 Studies have shown that Mohs micrographic surgery may be more effective with recurrence rates of 12%.46 Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been advocated by some authors, although there are minimal studies in this area.23 Orbital exenteration is recommended for extensive orbital or bulbar conjunctival disease. Radiation has not been shown to be effective.

In 1967, Muir and Torre independently described a syndrome of sebaceous cutaneous neoplasms, keratoacanthomas, and internal malignancy.50,51 The occurrence of Muir–Torre syndrome in patients with an identified sebaceous neoplasm has been reported as high as 42%, and patients present with sebaceous neoplasm at a mean age of 63.26

Muir–Torre syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. It occurs due to inactivating germ-line mutations in the DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2, MLH1, and MSH6, leading to microsatellite instability.12 MSH2 is the most commonly mutated gene.52 Muir–Torre syndrome is considered a phenotypic variant of the Lynch Syndrome, or hereditary nonpolyposis coli cancer family syndrome, which is also associated with defects in the DNA mismatch repair system.

Muir–Torre syndrome is characterized by sebaceous neoplasms, keratoacanthomas, internal malignancies, and personal or family history of Muir–Torre syndrome. Internal malignancy usually precedes cutaneous lesions in 59% of patients. However, up to 32% of cases report the development of a sebaceous neoplasm occurring prior to visceral malignancy.26 The sebaceous adenoma is the most specific marker for Muir–Torre syndrome, occurring in 68% of cases, but sebaceous hyperplasia, cystic sebaceous neoplasms, and sebaceous carcinoma can also be seen.26 Extrafacial sites are more common in Muir–Torre syndrome than the typical central facial location for sebaceous neoplasms.40

The most common visceral malignancy is colon cancer, followed by genitourinary cancers, breast cancer, and hematologic disorders. MSH2 mutations are associated with a higher risk of colon cancer, whereas MSH6 mutations are associated with increased endometrial cancer.53

Histopathology is consistent with that of the sebaceous neoplasm present in the individual. Other diagnostic methods include immunohistochemical staining for mismatch repair genes, which has been supported as a sensitive, rapid, inexpensive, convenient method for screening patients with suspected Muir–Torre syndrome.54 Gene sequencing confirms the diagnosis. Sebaceous neoplasms and keratoacanthomas in Muir–Torre syndrome are now included in the tumors to be tested for microsatellite instability via genotyping.12

Visceral tumors tend to behave less aggressively in Muir–Torre syndrome than in sporadic tumors, with a longer median survival in patients with Muir–Torre syndrome for the same tumor types.12 Aggressive cancer surveillance with colonoscopy and urinary cytology should be performed in these patients. Genetic counseling should also be provided.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for cutaneous lesions. Clinically involved nodes should also be removed. Low dose isotretinoin has been effective.26

Apocrine Neoplasms

Sweat gland neoplasms have traditionally been divided into apocrine tumors and eccrine tumors. However, the distinction between these can be quite difficult due to numerous terms applied to the same histological entity, overlap between classic apocrine and pure eccrine features, and the coexistence of both tissue types in hamartomas or mixed tumors.

The anatomic distribution of apocrine tumors reflects that of the normal location of glands producing apocrine secretion. Therefore, these lesions are generally confined to the head and neck, axilla, genitals, and perianal skin. Additional sites include the umbilicus, eyelid (Moll’s glands), areola, and external auditory meatus.6

Apocrine tumors are generally benign, although they possess the ability to degenerate into malignant lesions. An adnexal carcinoma developing from its benign counterpart generally has a history of explosive enlargement of a stable longstanding plaque or nodule. Adnexal carcinomas that develop de novo are more difficult to diagnose clinically, and require histopathologic evaluation. Features such as asymmetry, lack of circumscription, and infiltrative growth pattern support a malignant diagnosis. Histologically, these must be differentiated from cutaneous metastases from breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Malignant adnexal tumors rarely metastasize, and treatment of choice is often Mohs micrographic surgery or local excision.

Histopathologically, apocrine lesions are characterized by cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, eccentric basally located nuclei, and decapitation secretion in the luminal cells. Cells contain periodic acid Schiff (PAS) positive diastase resistant granules. The luminal cells are also reactive to Carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), while the secretory cells are positive for low molecular weight cytokeratin and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15).6

Apocrine hidrocystomas are relatively common cystic lesions that present in middle-aged or elderly individuals. There is a slight female predilection.55,56

Apocrine hidrocystomas arise from a benign proliferation of apocrine glands.

The cystic lesions typically present as solitary, smooth, translucent, flesh-colored or bluish, 1–3 mm papules on the head or neck, particularly in the periorbital region (Fig. 119-3A). Rare presentations include multiple lesions, giant tumors, and childhood onset.57 Apocrine hidrocystomas have been reported to appear within nevus sebaceus.23,55

Multiple lesions on the bilateral upper and lower eyelid margins are seen in Schopf–Schulz–Passarge syndrome, an ectodermal dysplasia characterized chiefly by multiple eyelid apocrine hidrocystomas, palmoplantar keratoderma, hypodontia, hypotrichosis, and nail dystrophy. While an autosomal recessive inheritance has been suggested, it can also be sporadic.58,59

On histologic examination, there is a unilocular or multilocular cyst located in the dermis. The epithelial lining consists of a single or double layer of cuboidal–columnar epithelium lying adjacent to an outer myoepithelial layer. Decapitation secretion is notable. Prominent papillations protruding into the lumen are seen in some cases (Fig. 119-3B).55

Lesions tend to be asyptomatic, and enlarge until a certain size is attained.

The treatment of choice for solitary lesions is surgical excision. Multiple lesions can be treated with electrodessication and curettage, carbon dioxide or pulsed dye lasers, local application of trichloroacetic acid, topical atropine, or botulinum toxin.60–63

Apocrine nevus is a rare hamartoma consisting of a proliferation of normal appearing apocrine glands in the dermis.

There are two clinical variants of apocrine nevus. A pure apocrine nevus is quite rare, and presents as a unilateral or bilateral, soft, lobulated, dermal mass in the axilla or scalp.1 A more common variant occurs as a part of a nevus sebaceus. Cases of apocrine nevus occurring as multiple papules on the chest have been reported.64

There are numerous, discrete, closely spaced tubular structures in the dermis and/or subcutaneous fat. The tubules are lined with typical apocrine glandular epithelium and contain a homogenous vacuolated pink secretion. An apocrine nevus that develops within a nevus sebaceous is usually deeper in the dermis and can coexist with syringocystadenoma papilliferum or trichoblastoma.23

The treatment of choice is surgical excision.

Apocrine fibroadenoma is a rare cutaneous apocrine neoplasm that occurs primarily in women younger than 25 years of age.1,65

Apocrine fibroadenoma is considered analogous to fibroadenoma of the breast.65 The etiology is unclear. Some feel that it most likely results from a proliferation of ectopic mammary tissue in response to excessive circulating estradiol over progesterone, whereas others believe it is derived from apocrine tissue.

Apocrine fibroadenoma typically presents as single or multiple firm, rubbery, smooth, mobile, painless nodules up to 2 cm in diameter. It most commonly occurs in the axilla, vulva, and perianal region.65

Histopathology reveals a variably hyalinized stroma surrounding a proliferation of ductal structures with decapitation secretion.

The treatment of choice is complete surgical excision.

Erosive adenomatosis, also known as adenoma of the nipple or florid papillomatosis, is a rare benign neoplasm of breast lactiferous ducts. The peak incidence is in women in the fifth decade, although it has been reported in males and children.66

The tumor derives from terminal lactiferous ducts and subareolar breast tissue.

The classic presentation of erosive adenomatosis is with a unilateral erythematous, eroded, crusted papule on the nipple of middle-aged females. Ulceration and serosanguinous discharge may also occur. The lesion is usually asymptomatic, but patients may complain of irritation, burning, pain, and pruritus. Secretion may vary during the menstrual cycle.67 Clinically, the lesion is often indistinguishable from Paget’s disease. Other entities in the differential diagnosis include allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and infection.

Microscopically, erosive adenomatosis reveals a nonencapsulated endophytic proliferation of tubular structures in the dermis with a verrucous or ulcerated surface. Some of the tubular structures exhibit cystic dilations with discrete papillations. The tubules are lined by an inner apocrine secretory epithelium and an outer myoepithelial layer. Differentiating the histologic pattern from intraductal carcinoma of the breast is important. A lack of atypia and necrosis support the diagnosis of erosive adenomatosis.

Studies have not supported a strong association with breast adenocarcinoma or fibrocystic disease of the breast.66

Surgical excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are effective treatment choices. Traditionally, complete excision involved removal of the entire nipple and underlying tissue. However, this treatment is associated with recurrence and significant deformation of the cosmetically and functionally sensitive nipple requiring reconstruction.68,69 More recently, Mohs micrographic surgery has been an effective treatment, with a lower recurrence rate, and minimal deformation. Unique reconstructive techniques, including closure with a purse-string suture, have been employed after Mohs micrographic surgery.70

Hidradenoma papilliferum, also known as papillary hidradenoma, is a relatively uncommon benign neoplasm most commonly presenting in females between the ages of 30 and 49 years.1,71

This benign neoplasm develops from the anogenital apocrine glands.

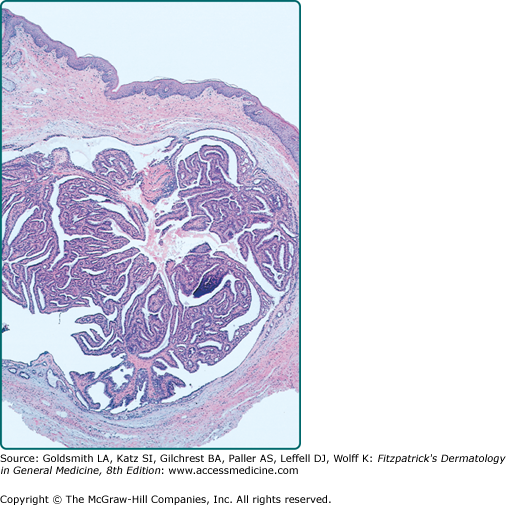

The lesion typically presents as a small, unilateral, asymptomatic, flesh-colored nodule on the female vulva. There are reports of ectopic or nonanogenital lesions on the head and neck, where it presents as a subcutaneous nodule, tumor, or cyst. Lesions have been reported on the eyelid, external auditory canal, lip, and nasal ala.72 Hidradenoma papilliferum has also been reported to develop within a nevus sebaceous.23

On histopathology, there is a well-circumscribed dermal nodule that is partly solid or solid-cystic. It lacks an epidermal connection. The nodule consists of an anastomosing pattern of numerous glandular structures and papillary folds. The lumina are made of a double layer of cells: an inner layer of secretory cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, and an outer layer of cuboidal myoepithelial cells (Fig. 119-4). Hidradenocarcinoma papilliferum is notable for high cellularity and asymmetry.

Hidradenoma papilliferum usually follows a benign course. Malignant transformation into hidradenocarcinoma papilliferum has been reported. It presents as a small, solitary, ulcerated nodule in the anogenital region, and rarely in the axilla. Patients may complain of slight pain or brown watery discharge. Fatal metastases, initially involving regional lymph nodes, have been described. Lesions have been seen in association with extramammary Paget’s disease.1,73

A fatal metastasizing squamous cell carcinoma arising in a hidradenoma papilliferum has also been reported.74 There are also rare cases of ductal carcinoma in situ arising in hidradenoma papilliferum.75

The treatment of choice is surgical excision. In the case of perianal tumors, consultation with colorectal surgery is recommended to preserve anal sphincter function. Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be of value in patients with hidradenocarcinoma papilliferum.

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a rare benign adnexal neoplasm that presents in young adults. Fifty percent are present at birth or early childhood, and an additional 15%–20% develop before puberty.76,77

The derivation of syringocystadenoma papilliferum is unclear, with evidence supporting both apocrine and eccrine origin. Forty percent of lesions develop within a nevus sebaceous.78 Some studies show that mutations in the tumor suppressors, PTCH and p16, may play a role in the evolution of syringocystadenoma papilliferum.79

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, firm, pink papule or plaque measuring 1–3 cm. A small fistula draining clear, bloody, or malodorous fluid may develop (Fig. 119-5A). At puberty, the lesion often grows and becomes increasingly papillated and hyperkeratotic. The most common location is the scalp.80 Rare presentations include unusual locations such as the trunk, arms, or vulva, and multiple or linearly arranged cutaneous nodules.

The lesion has been seen in conjunction with a wide variety of other adnexal tumors including nevus sebaceous, apocrine nevus, tubular apocrine adenoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, clear cell syringoma, eccrine nevus, verrucous carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma.80 This tumor has also been noted in a patient with focal dermal hypoplasia due to a novel PORCN mutation. Additional apocrine neoplasms seen in this genetic condition include apocrine nevi and apocrine hidrocystomas.81

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum presents with papillomatous epidermal invaginations lined with a double layer epithelium composed of basilar cuboidal cells and an inner columnar layer of secretory cells (Fig. 119-5B). A plasma cell rich infiltrate is also characteristic. There is typically a connection between the epithelial invagination and adjacent glands in the dermis.

The malignant counterpart, syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum, is characterized by asymmetry, poor circumscription, extension to the deep subcutaneous tissue, and increases in cellularity, cellular atypia, and mitoses.

Basal cell carcinoma has been reported to occur in as high as 9% of cases, although this has not been corroborated by others.76,78 Malignant degeneration into syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum has been reported, with signs of malignant behavior including rapid growth, ulceration, pain, and pruritus.82,83 There is a low risk of regional lymph node metastases, while distant metastases have not been reported.

Complete surgical excision is recommended given the malignant potential of syringocystadenoma papilliferum, although the benefit of prophylactic excision is unclear. In anatomic areas unfavorable for excision or grafting, carbon dioxide laser may be an alternative option.84 For syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum, excision and Mohs micrographic surgery have been effective treatment options.82

Cylindromas are benign neoplasms that are more common in females and typically present in the third decade.1,85

Cylindromas are thought to originate from apocrine glands although some support an eccrine or follicular origin.86 Multiple cylindromas are seen in Brooke–Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition with variable penetrance and expressivity, that presents with multiple cylindromas, eccrine spiradenomas, and trichoepitheliomas. Inactivating germ-line mutations or loss of heterozygosity in the tumor suppressor gene CYLD result in this disfiguring condition.87 CYLD encodes a ubiquitin hydrolase implicated in the negative regulation of cell proliferation through the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway. Mutations in CYLD cause an increased expression of NF-κB, and lead to apoptotic resistance and development of tumors seen in Brooke–Spiegler syndrome.88 Some also believe that ultraviolet radiation may play a role given that the most common presentation is on sun-exposed areas such as the face and scalp.

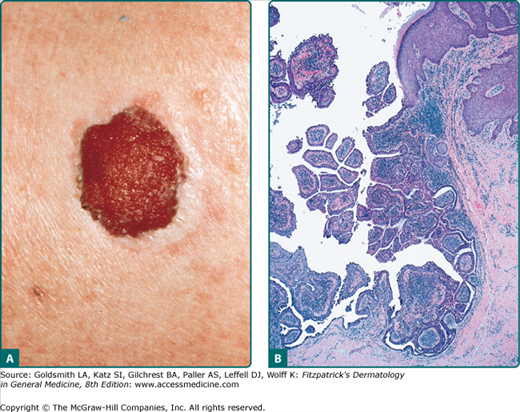

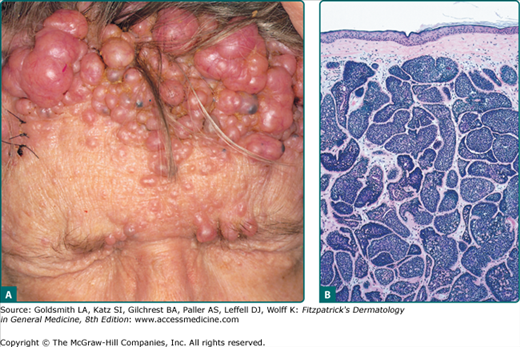

Cylindromas most commonly present as slow growing, pink, firm, smooth, alopecic, painful nodules ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 6 cm on the scalp. When multiple lesions coalesce on the scalp forming a confluent mass, the term “turban tumors” has been applied (Fig. 119-6A). While they can present as solitary lesions, the familial variant typically manifests with numerous tumors. Aside from pain, conductive deafness and sexual dysfunction have been reported in periauricular and pubic lesions.86

Patients with Brooke–Spiegler syndrome present with cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, spiradenomas, sebaceous nevi, basal cell carcinoma and milia.89 Incidental associations with cylindroma include polycystosis of the lungs and kidneys, cervical, breast, and parotid carcinomas, and multiple fibromas.89

Cylindromas are characterized by dermal aggregates of large epithelial cells with abundant cytoplasm in the center and small basaloid cells in the periphery. The nodules are lined by thick basement membrane-like material, and arranged in a classic jigsaw puzzle pattern (Fig. 119-6B).90

Patients with Brooke–Spiegler syndrome are at risk for basal cell carcinomas, tumors of the salivary glands, and parotid adenomas.91 Malignant degeneration of cylindromas into cylindrocarcinoma has been reported. Malignant transformation more commonly occurs in cases of multiple tumors, females, and in middle-aged to elderly patients.92 Clinical signs include pink to blue discoloration, ulceration, rapid growth, and bleeding. These are highly aggressive tumors with potential for local destructive growth, metastases, and recurrence.92,93 Metastases to the lymph nodes, stomach, thyroid, liver, lung, and bones have been reported.

The treatment of choice for a cylindroma is surgical excision. In the case of multiple confluent tumors on the scalp, this can pose a challenge. Entire scalp excision carries the risk of significant blood loss requiring a blood transfusion and skin graft failure.85 Alternative treatments include electrosurgery, dermabrasion, carbon dioxide laser, cryotherapy, and radiotherapy.85,94 New insights into the role of CYLD in the NF-κB pathway has lead to the use of topical salicylic acid in cylindromatosis, with some reports showing complete remission after 6 months.95

Apocrine adenocarcinoma comprises a rare group of cutaneous adenocarcinomas that show apocrine differentiation. It most commonly presents in middle-aged to elderly males.96

The lesion usually arises de novo; however, there are reports of it developing in association with apocrine adenoma, cylindroma, nevus sebaceus, extramammary Paget’s disease, and accessory nipple.96,97

There is significant variation in the clinicopathologic presentation of apocrine adenocarcinoma. It generally presents as an indolent, slow-growing, rubbery, solid to cystic nodule or tumor ranging in size from 1.5 to 8 cm. The color varies from red to purple, and ulceration may be present.98 There are rare presentations that can mimic cellulitis.99 The most common location is the axilla followed by the anogenital skin, regions of high apocrine gland density.98 Less frequent locations include the scalp, forehead, eyelid, upper lip, chest, nipple, and finger.96 Patients may complain of pain, restricted range of motion, ulceration, and purulence.96 Clinically, cutaneous metastases from breast and gastrointestinal cancers must be considered.

Histopathologically, apocrine adenocarcinoma presents with a dermal and/or subcutaneous non encapsulated tumor with infiltrative margins. The carcinoma is composed of large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei, mitotic figures, and decapitation secretion. The epithelial component shows variable papillary, cribiform or trabecular, and solid patterns.100–102 Signet ring cells and pagetoid spread have been reported.100

Apocrine adenocarcinoma is a locally invasive neoplasm with potential for regional lymph node metastases. Despite its aggressive behavior, mortality is relatively low.98,100 Local recurrence after wide local excision has been reported at 27.5%.96 Over 40% of reported cases presented with nodal metastases at initial diagnosis. Distant metastases to the lungs, bones, brain, and parotid gland have been reported.96

The treatment of choice is wide local excision with clear margins. Some believe that there is a role for sentinel lymph node biopsy and nodal dissection given the high rate of regional nodal metastases.96 Adjunctive chemotherapy and radiation have been used. In some cases, the presence of steroid receptors in the tumor has lead to the use of tamoxifen.100

Eccrine Tumors

Eccrine glands are widely distributed in the skin. Therefore, eccrine tumors have a wider anatomic distribution than apocrine tumors. Histologically, eccrine tumors comprise a large spectrum of lesions with differentiation toward various portions of the normal eccrine apparatus, including intraepidermal (acrosyringium), dermal, and secretory ducts. The distinguishing feature is the tendency to form lumina with flattened epithelium. Distinction from apocrine tumors is not always straightforward, as decapitation secretion can be observed in certain tumors traditionally classified as “eccrine.” Similar to apocrine tumors, eccrine tumors are typically benign, but possess the ability to degenerate into malignant lesions.

Eccrine hidrocystomas are common lesions found in middle-aged to elderly patients, predominantly in females.103

Eccrine hidrocystoma is a benign proliferation of eccrine glands.

There are two clinical variants of eccrine hidrocystoma. Robinson first described multiple eccrine hidrocystomas in 1893.104 The solitary type was first reported by Chernosky and Smith in 1973.105 The lesions are typically translucent, skin-colored or blue, dome-shaped, cystic papules on the head and neck. Multiple lesions clustered in the periorbital region may be a sign of ectodermal dysplasia.103 Multiple lesions have also been associated with warm climates, hyperhidrosis, and Graves disease.106

The cyst lining is a double layer of flattened epithelium lacking decapitation secretion. Eosinophilic contents may be seen.

Eccrine hidrocystoma follows a benign course.

Solitary lesions can be surgically excised. Destructive methods such as electrodessication, curettage, laser ablation, and pulsed dye laser therapy have been employed but are often associated with scarring. Botulinum toxin injections have been used with success.103

Eccrine nevi, first described in 1976, encompass a variety of rare benign eccrine hamartomas that appear in childhood and adolescence.107 Some lesions may be congenital, whereas others present at advanced ages.108

Eccrine nevi originate from eccrine glands. Several distinct forms exist. The two main subtypes are the rare pure eccrine nevus and the common eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Other presentations include the mucinous eccrine nevus and porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN).109

The clinical presentation of eccrine hamartomas is variable depending on the subtype. Pure eccrine nevi classically present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, hyperhidrotic plaque with little to no epidermal change. Hyperhidrotic episodes are triggered by temperature, stress, and exercise. The most common location is the forearm (50%) followed by the back and trunk.109,110 Rare presentations include hyperpigmented patches, linear lesions, centrally depressed plaques, and scaly borders.110

Eccrine angiomatous hamartomas (EAH) are more common and are often present at birth. They present with a solitary or multiple flesh-colored, red, or blue–brown nodules or plaques on the extremities, especially the legs. EAH can be painful.109

Mucinous eccrine nevi are extremely rare lesions that present with nodules or plaques with hyperhidrosis.109,111 Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN) is a rare disorder of keratinization involving the intraepidermal eccrine duct or acrosyringium.112 PEODDN presents with congenital punctuate keratoses on the hands and feet, and has been associated with deafness, developmental delay, seizures, scoliosis, anhidrosis, alopecia, onychodysplasia, and palmoplantar involvement.113 Lesions are typically linear and follow the lines of Blaschko.

There are rare reports of coexistence with other cutaneous lesions such as clear cell syringoma and neurofibromatosis I.114

There is an increase in the number or size of normal eccrine glands. EAH also shows an increase in the number of capillaries. Mucinous eccrine nevi are characterized by large mucin deposits surrounding eccrine glands. PEODDN demonstrates parakeratotic coronoid lamellae over the eccrine ostia.109

These lesions are benign. Indications for treatment include pain and excessive hyperhidrosis.

The treatment of choice is surgical excision. Often, the lesions are quite large and surgery is not feasible. Alternative therapies include aluminum chloride, systemic and topical anticholinergic agents, clonazepam, antidepressants, and botulinum toxin injections.108 PEODDN has been treated with the carbon dioxide laser and topical retinoids.115

Syringomas are common benign neoplasms most frequently seen in adult females. There is an increased frequency in Down’s syndrome, with 18% of patients exhibiting this cutaneous sign. An increased frequency has also been observed in Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers Danlos, and Nicolas balus syndrome. An eruptive form most commonly presents in adolescent females. The clear cell variant has been linked to diabetes.116

Syringomas derive from the intradermal eccrine duct or acrosyringium. Local factors, including ductal obstruction by keratin plugs leading to ductal proliferation, may play a role in pathogenesis.117,118 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear. It has been hypothesized that these eruptive lesions demonstrate reactive eccrine gland proliferation following an inflammatory condition.119