Antihistamines: Introduction

|

Histamine is a low-molecular-weight amine derived from l-histidine that is produced throughout the body. By means of four known types of receptors, histamine affects cellular growth and proliferation, modulates inflammation, and acts as a neurotransmitter. Both H1 and H2 histamine receptors are widely expressed. H1 receptors are found on neurons, smooth muscle, epithelium and endothelium, and multiple other cell types. H2 receptors are located in the gastric mucosa parietal cells, smooth muscle, epithelium and endothelium, heart, and other cell types as well. H3 and H4 receptors have more limited expression. H3 receptors are found primarily on histaminergic neurons, whereas H4 receptors are highly expressed in bone marrow and on peripheral hematopoietic cells.

H1 Antihistamines

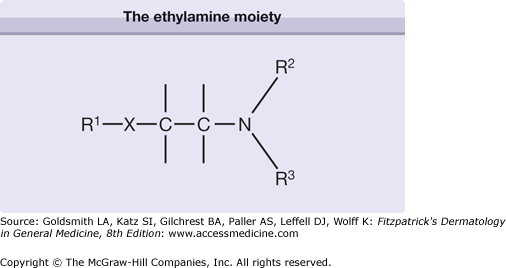

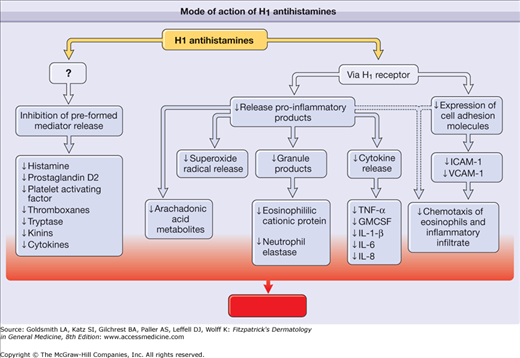

H1 antihistamines are inverse agonists that reversibly bind and stabilize the inactive form of the H1 receptor, thereby favoring the inactive state1 (Box 229-1). The backbone structure of H1 antihistamines is depicted in Fig. 229-1. By means of the H1 receptor, H1 antihistamines decrease production of proinflammatory cytokines, expression of cell adhesion molecules, and chemotaxis of eosinophils and other cells (Fig. 229-2).2 H1 antihistamines may also decrease mediator release from mast cells and basophils through inhibition of calcium ion channels. In addition to having antihistamine actions, first-generation H1 antihistamines can also act on muscarinic, α-adrenergic, and serotonin receptors and cardiac ion channels. Some of the more serious adverse effects associated with first-generation H1 antihistamines, such as urinary retention, hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmias, are mediated through these other receptors. The first-generation antihistamines are divided into six groups on the basis of chemical structure: (1) ethylenediamines, (2) ethanolamines, (3) alkylamines, (4) phenothiazines, (5) piperazines, and (6) piperidines3 (see Fig. 229-1). The presence of multiple aromatic or heterocyclic rings and alkyl substituents enhances the lipophilicity of these compounds, which allows penetration of the blood-brain barrier.

|

Figure 229-2

Mode of action of H1 antihistamines. By means of the H1 receptor, H1 antihistamines inhibit the release of preformed mediators and decrease the production of proinflammatory cytokines, the expression of cell adhesion molecules, and chemotaxis of eosinophils and other cells. ↓ = decreased; GMCSF = granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; ICAM-1 = intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 = interleukin-1β, interleukin 6, interleukin 8; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; VCAM-1 = vascular cellular adhesion molecule 1.

Many of the low-sedating or second-generation H1 antihistamines are chemically derived from first-generation agents.2 For example, cetirizine is a metabolite of hydroxyzine. The second-generation H1 antihistamines bind noncompetitively to the H1 receptor. They are not easily displaced by histamine, dissociate slowly, and have a longer duration of action than first-generation H1 antihistamines.3 Due to the selectivity of second-generation drugs for the H1 receptor and their reduced lipophilicity, these drugs are far less likely to cause sedation and have different safety profiles than the first-generation drugs.

Some low-sedating H1-type antihistamines affect the trafficking of cells in the skin and other tissues, presumably by modulating the release of inflammatory mediators and the expression of adhesion molecules. In a skin chamber challenge model, cetirizine administration reduced eosinophil influx after allergen challenge. This effect seems to be specific to cutaneous allergic responses, because similar studies involving nasal challenges have not shown any decrease in eosinophil accumulation in nasal secretions. In vitro, cetirizine inhibits eosinophil, monocyte, and T-lymphocyte chemotaxis to N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine and platelet-activating factor.4 H1 antihistamines may also modulate the expression of cellular adhesion molecules such as antigen-induced intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, and endothelium, and influence the release of inflammatory mediators from leukocytes.5 Desloratadine and emedastine were found to inhibit platelet-activating factor-induced eosinophil chemotaxis, tumor necrosis factor-α-induced eosinophil adhesion, and spontaneous and phorbol myristate-induced superoxide generation.6,7

After oral administration, effects of sedating H1 antihistamine can be observed within 30 minutes to 1 hour and generally persist for 4–6 hours, although the effects of some agents may last for 24 hours and longer.8 For example, after oral administration of a single dose, the serum half-lives of brompheniramine, chlorpheniramine, and hydroxyzine exceed 20 hours in adults. H1 antihistamines are metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme 3A4, forming glucuronides before excretion in urine.

The potency and relative concentration in the skin of H1 antihistamines can be compared by their inhibition of the cutaneous wheal-and-erythema response to histamine injected cutaneously. In placebo-controlled, double-blind studies, no evidence of tolerance or tachyphylaxis was demonstrated in suppression of skin test reactivity over a 3-month period.2 Suppression of skin test reactivity may be observed for up to 7 days after discontinuation of a regularly used sedating H1 antihistamine.

Oral sedating H1-type antihistamines are typically administered in divided doses at intervals of 4–8 hours (see Section “Dosing Regimens”), although once-daily dosing may suffice for agents with longer serum half-lives. Topical formulations for dermatologic use are available, although these preparations tend to be less effective and are associated with the development of delayed contact reactions.

Most low-sedating, or second-generation, H1 antihistamines are administered once or twice daily and achieve peak plasma concentrations within two half-lives, although this interval can vary among different drugs and individuals. These drugs generally achieve higher concentrations in the skin than their first-generation counterparts, and a single dose can suppress the wheal and erythema reaction from 1–24 hours.9–12 Regular use prolongs this effect; for example, 6 days of daily cetirizine use results in 7 days of suppression of the wheal and erythema response.

Terfenadine, astemizole, loratadine, acrivastine, mizolastine, ebastine, and oxatomide are metabolized in the liver via the hepatic enzyme CYP 3A4. Cetirizine, fexofenadine, levocabastine, desloratadine, and levocetirizine undergo minimal hepatic metabolism, which reduces the likelihood of interactions with other drugs.8

In healthy adults, cetirizine and levocetirizine reach peak concentrations around 1 hour after administration, with an elimination half-life of approximately 8 hours.13 Lower dosages are used in patients with impaired renal or hepatic function. Fexofenadine generally reaches peak concentration at 2–3 hours, with an elimination half-life of 14 hours.13 Dosage adjustment is recommended for patients with decreased creatinine clearance, including the elderly; however, patients with hepatic disease do not require dosage adjustment because fexofenadine undergoes almost no hepatic metabolism.13 Loratadine’s half-life ranges on average from 8–24 hours, depending on hepatic function. Ebastine, which is metabolized to form its carboxylic acid metabolite, carebastine, has a half-life of 15 hours.13 The dosage should be adjusted in patients with impaired renal function. Pharmacogenetics may also influence drug metabolism and clearance. In a series of pharmacokinetic studies, approximately 7% of all subjects and 20% of African-Americans were slow metabolizers of desloratadine.14 Comparable differences may exist for other H1 antihistamines.

|

H1 antihistamines are used to treat pruritus of various etiologies, urticaria, and angioedema (Box 229-2). In particular, H1 antihistamines appear to be effective in treating physical urticarias and dermatographism, in addition to chronic idiopathic urticaria. They are not as effective in treating hereditary and acquired angioedema syndromes and urticarial vasculitis. Few well-controlled, blinded studies of the first-generation H1-type drugs exist. The general tendency for most chronic urticarias to improve with time and the difficulty in making quantitative assessment of the condition further complicate clinical studies. Comparative studies of the groups of H1-type antihistamines have shown them to be of equal efficacy.2 If an agent from one therapeutic group of H1-type antihistamines proves ineffective, then a trial with an agent from another group may be initiated. In several double-blind, placebo-controlled, or parallel studies, the low sedating H1-type antihistamines terfenadine, astemizole, cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, desloratadine, acrivastine, mizolastine, azelastine, ebastine, and oxatomide were superior to placebo in the treatment of urticaria and angioedema.15–20 Trials comparing different second-generation antihistamines with one another have not shown any one agent to be consistently superior, although cetirizine and levocetirizine have overall fared best in comparative trials.2,15,21–24

Both sedating and low-sedating H1 antihistamines are used to treat pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis, although their efficacy has not been proved by rigorous clinical trials. In the 18-month Early Treatment of the Atopic Child study, cetirizine afforded a steroid-sparing benefit to children with the most severe atopic dermatitis, but no consistent benefit was observed in children with more moderate disease.25 A meta-analysis of 16 studies conducted from 1966 through 1999 does not indicate a major role for either first- or second-generation H1 antihistamines in the treatment of atopic dermatitis, although no randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies are included in this analysis.26

H1 antihistamines are commonly used to treat cutaneous and systemic mastocytosis, although large comparative treatment trials are not available.27 One early double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated the efficacy of H1 and H2 antihistamines in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis.28 In a later small trial, azelastine compared favorably with chlorpheniramine in the suppression of pruritus in patients with mastocytosis.29

Pruritus associated with other conditions, such as allergic contact dermatitis and other forms of eczematous dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic mastocytosis, mosquito bites, infestations, and pruritus secondary to underlying medical disorders or idiopathic pruritus, also may be relieved by H1 antihistamines, although controlled trials do not exist.30 In these conditions, the sedative effects of the first-generation agents may be advantageous, permitting more restful sleep. H1 antihistamines are also used as pretreatment before certain procedures for patients with a history of radiocontrast media and transfusion reactions.

The dosing regimens for H1 antihistamines are shown in Table 229-1. Doses of second generation antihistamines as high as four times the recommended dosage have been advocated in international guidelines on chronic urticaria31,32 However, the limited number of published studies evaluating this approach have not demonstrated a clear increase in efficacy.33

Drug | Formulation | Dosage | Conditions Requiring Dosage Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

First-generation H1 | |||

Chlorpheniramine | 2-, 4-, 8-, 12-mg tablet 2 mg/5 mL syrup | Adult: 4 mg tid, qid; 8–12 mg bid Age 6–11 years: 2 mg q4–6h | Hepatic impairment |

Cyproheptadine | 4-mg tablet | Adult: 4 mg tid, qid | Hepatic impairment |

2 mg/5 mL syrup | Age 7–14 years: 4 mg bid, tid | ||

Diphenhydramine | 25-, 50-mg tablet 12.5 mg/5 mL syrup 50 mg/15 mL syrup 6.25 mg/5 mL syrup 12.5 mg/5 mL syrup | Adult: 25–50 mg q4–6h Age 6–12 years: 12.5–25 mg q4–6h Age <6 years: 6.25–12.5 mg q4–6h | Hepatic impairment |

Hydroxyzine | 10-, 25-, 50-, 100-mg tablet 10 mg/5 mL syrup | Age ≥6 years: 25–50 mg q6–8h or qhs Age <6 years: 25–50 mg qd | Hepatic impairment |

Tripelennamine | 25-, 50-, 100-mg tablets | Adult: 25–50 mg q4–6h | Hepatic impairment |

Second-generation H1 antihistamines | |||

Acrivastinea | 8-mg tablet | Adult: 8 mg tid | Renal impairment |

Azelastine | 2-mg tabletb 0.1% nasal spray | Adult: 2–4 mg bid Age 6–12 years: 1–2 mg bid 2 sprays/nostril bid | Renal and hepatic impairment |

Cetirizine | 5-, 10-mg tablet 5 mg/mL syrup | Age ≥6 years: 5–10 mg qd Age 2–6 years: 5 mg qd Age 6 months–2 years: 2.5 mg qd | Renal and hepatic impairment |

Desloratadine | 2.5-, 5-mg tablet 5 mg/mL syrup | Age ≥12 years: 5 mg qd Age 6–12 years: 2.5 mg qd Age 1–6 years: 1.25 mg qd Age 6–12 months: 1 mg qd | Renal and hepatic impairment |

Ebastineb | 10-mg tablet | Age ≥6 years: 10–20 mg qd Age 6–12 years: 5 mg qd Age 2–5 years: 2.5 mg qd | Renal impairment |

Fexofenadine | 30-, 60-, 120-, 180-mg tablet | Age ≥12 years: 60 mg qd, bid; 120–180 mg qd Age 6–12 years: 30 mg qd, bid | Renal impairment |

Levocetirizine | 5-mg tablet | Age ≥6 years: 5 mg qd | Renal and hepatic impairment |

Loratadine | 10-mg tablet 5 mg/mL suspension | Age ≥6 years: 10 mg qd Age 2–9 years: 5 mg qd | Renal and hepatic impairment |

Mizolastineb | 10-mg tablet | Adult: 10 mg qd | Hepatic impairment |

The H1 antihistamines are considered first-line therapy in the treatment of chronic idiopathic and physical urticarias and may be useful in treating other conditions in which histamine-driven pruritus is a major feature. The lowest effective dosage is preferred to minimize dose-related side effects, such as sedation. After several days of therapy, the dosage may be increased and titrated. Occasionally, gradual escalation of dosing permits the development of tolerance to sedation, which allows higher dosages to be used to treat certain conditions, such as refractory chronic urticaria. Ingestion of the medication with food may alleviate any gastrointestinal discomfort, although patients should be advised to avoid taking fexofenadine with antacids, which can interfere with drug absorption. Individuals with comorbid conditions, such as renal or hepatic disease, may require lower dosages due to impaired metabolism of these drugs. Certain special patient populations, including children, the elderly, and pregnant or breastfeeding women, may also need dosage adjustments (see Section “Special Patient Populations”). Some situations may call for more careful assessment of H1 antihistamine therapy2 (Box 229-3).

|

Therapeutic endpoints are evaluated by observation of clinical signs and symptoms (e.g., severity of pruritus; wheal number, size, and frequency). As for drug toxicity, no particular monitoring beyond the usual surveillance for adverse effects is required in most cases. Certain individuals, such as patients with impaired metabolism or other comorbid conditions and those taking other medications, may require closer monitoring and counseling regarding the use of H1 antihistamines. Because of reports of hepatotoxicity, some sources recommend periodic liver transaminase evaluation when cyproheptadine is used.34

Adverse effects are listed in Box 229-4. Sedation is the most commonly reported problem, primarily with first-generation H1 antihistamines.2,3,8 The sedative effect is more pronounced with the ethanolamine and phenothiazine groups and is less marked with the alkylamine group. The sedative effect may diminish after a few days of continual use of H1-type antihistamines. If tolerance to sedation does not occur, an agent from another group should be tried. The use of H1-type antihistamines has been associated with an increase in occupational injuries and automobile accidents.35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree