Anetoderma and Other Atrophic Disorders of the Skin: Introduction

|

Anetoderma

The lesions in anetoderma usually occur in young adults between the ages of 15 and 30 years and more frequently in women than men. Anetoderma is rare, but the incidence is unknown. Several hundred cases have been reported.1–4

The pathogenesis of anetoderma is unknown. The key defect is damage to the dermal elastic fibers. Anetoderma may be considered to be unusual scars, because scars also have decreased elastic tissue. The loss of dermal elastin could be the result of an impaired turnover of elastin caused by either increased destruction or decreased synthesis of elastic fibers.

All types of anetoderma are characterized by a circumscribed loss of normal skin elasticity. The characteristic lesions are flaccid circumscribed areas of slack skin with the impression of loss of dermal substance forming depressions, wrinkling, or sac-like protrusions (Fig. 67-1). These atrophic, skin-colored, or blue–white lesions are 5–30 mm in diameter. The number varies from a few to hundreds. The skin surface can be wrinkled, thinned, and often depigmented, and a central depression may be seen. Coalescence of smaller lesions can give rise to larger herniations. The examining finger sinks without resistance into a distinct pit with sharp borders as if into a hernia ring (buttonhole sign). The protrusion reappears as soon as the pressure from the finger is removed.4

The most common sites for these asymptomatic lesions are the chest, back, neck, and upper extremities. They usually develop in young adults, and new lesions often continue to form for many years as the older lesions fail to resolve.

Primary anetoderma occurs when there is no underlying associated skin disease (i.e., it arises on clinically normal skin). It is historically subdivided into two types: (1) those with preceding inflammatory lesions, mainly erythema (the Jadassohn–Pellizzari type), and (2) those without preceding inflammatory lesions (the Schweninger–Buzzi type). This classification is only of historical interest, because the two types of lesions can coexist in the same patient; the prognosis and the histopathology are also the same.4

True secondary anetoderma implies that the characteristic atrophic lesion has appeared in the exact same site as a previous specific pathology; the most common causes are probably acne and varicella. Numerous and heterogeneous dermatoses have been associated with secondary anetoderma, namely syphilis, Lyme disease, molluscum contagiosum, pilomatricomas, juvenile xanthogranuloma, xanthomas, granuloma annulare, leprosy, discoid lupus, sarcoidosis, and lichen planus, to mention only a few. Anetoderma has also been described in premature infants and, in some cases, it may have been related to the use of cutaneous monitoring leads or adhesives.5 Both types may be associated with an underlying disease, mainly antiphospholipid syndrome6 and human immunodeficiency virus. Although most cases are sporadic, rare cases of familial anetoderma have been recently described and are usually not associated with preexisting lesions.7

In routinely stained sections, the collagen fibers within the dermis of affected skin appear normal. Perivascular lymphocytes are often present in all types of anetoderma and do not correlate with clinical inflammatory findings.8

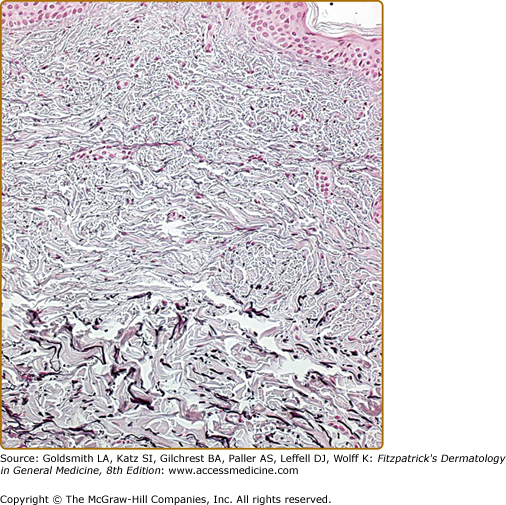

The predominant defect as revealed by elastic tissue stains is a focal partial or complete loss of elastic tissue in the papillary and/or midreticular dermis. There are usually some residual abnormal, irregular, and fragmented elastic fibers (Fig. 67-2).9 Presumably, the weakening of the elastic network leads to flaccidity and herniation. Direct immunofluorescence sometimes shows linear or granular deposits of immunoglobulins and complement along the dermal–epidermal junction or around the dermal blood vessels in affected skin.10 Electron microscopy demonstrates that the elastic fibers are fragmented and irregular in appearance and occasionally can be engulfed by macrophages.

Anetoderma must be differentiated from other disorders of elastic tissue as well as atrophies of the connective tissue (Box 67-1).

ELEVATED | DEPRESSED |

|---|---|

Secondary anetoderma Acne scars Keloids Nevus lipomatosus superficialis Papular elastorrhexis Connective tissue nevi | Secondary anetoderma Glucocorticoid-induced atrophy Acne scars |

Keloids form nodules that are much firmer on palpation. A history of trauma is often elicited, and the pathology is very distinct.

Glucocorticoid-induced atrophy occurs most commonly over the triceps or buttocks at sites where injections are usually given. Clinically, the lesions resemble atrophoderma. History is obviously most helpful in making the diagnosis. On histopathology, polarization may show the steroid crystals in the dermis.

Nevus lipomatosus superficialis of Hoffman and Zurhelle presents as a clustered group of soft, skin-colored to yellow nodules usually on the lower trunk and buttocks and present since birth. Histology shows ectopic mature lipocytes located in the dermis.

Papular elastorrhexis is an acquired disorder characterized by white, firm nonfollicular papules measuring 1–3 mm, evenly scattered on the chest, abdomen, and back. It usually appears in adolescence or early adulthood. The pathology demonstrates focal degeneration of elastic fibers and normal collagen. There are no associated extracutaneous abnormalities. This is believed by some authors to be a variant of connective tissue nevi11 or an abortive form of the Buschke–Ollendorff syndrome,12 whereas others think that these represent papular acne scars.13 They are differentiated from anetoderma by being firm noncompressible lesions.

Middermal elastolysis (MDE) usually consists of larger areas with diffuse wrinkling without herniation and with elastolysis limited to the middermis (See below).

There is no regularly effective treatment. In secondary anetoderma, appropriate treatment of the inflammatory underlying condition might prevent new lesions. In patients with limited lesions that are cosmetically objectionable, surgical excision may be useful. Various therapeutic modalities have been tried but with no improvement of existing atrophic lesions, including intralesional injections of triamcinolone and systemic administration of aspirin, dapsone, phenytoin, penicillin G (benzylpenicillin), and vitamin E. Some authors have reported improvement with hydroxychloroquine.

Other Atrophic Disorders of the Skin

MDE is a rare acquired disorder of elastic tissue. It is characterized by patches and plaques of diffuse, fine, wrinkled skin, most often located on the trunk, neck, and arms. In 1977, Shelley and Wood reported the first case of “wrinkles due to idiopathic loss of middermal elastic tissue.”14 Since then, fewer than 100 cases have been reported. The vast majority of patients are Caucasian women between the ages of 30 and 50 years.15,16

The pathogenesis of this acquired elastic tissue degeneration is still unknown. Ultraviolet (UV) exposure has been postulated to be a major contributing factor in the degeneration of elastic fibers,17 including narrowband UVB.18 Other possible mechanisms include defects in the synthesis of elastic fibers, autoimmunity against elastic fibers, and damage to elastic fibers through the release of elastase by inflammatory cells or fibroblasts. More recent data suggest that inflammatory processes and an altered balance between matrix metalloproteinase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases are possibly involved in the pathogenesis of MDE.19

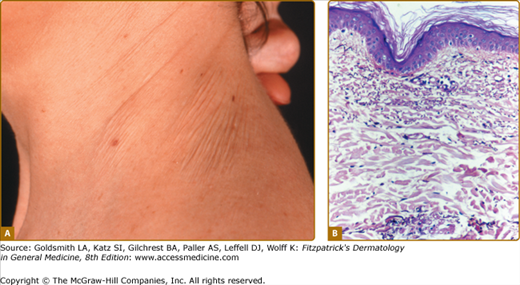

MDE is characterized by asymptomatic, well-demarcated, or diffuse areas of fine wrinkling (Fig. 67-3A). Rarely, erythematous patches, telangiectasias, or a reticular variant can be seen. Discrete perifollicular papules can be seen in some cases, leaving the hair follicle itself as an indented center. Lesions are typically found on the trunk, neck, and upper extremities. They are chronic and give the skin a prematurely aged appearance. There is usually no history of a preceding inflammatory dermatosis, but some patients report mild-to-moderate erythema. There is no associated systemic involvement.

Figure 67-3

Middermal elastolysis. A. Well-circumscribed area of fine wrinkling on the neck of a middle-aged woman. (Used with permission from Richard Dubuc, MD.) B. Histology of middermal elastolysis. Note selective loss of elastic fibers in the middermis. Normal elastic tissue is preserved in the superficial papillary dermis and in the reticular dermis (Weigert’s stain). (Used with permission from Danielle Bouffard, MD.)

The pathology shows a normal epidermis and, occasionally, a mild perivascular infiltrate in the dermis. The characteristic histology is seen on elastic tissue stains and reveals a selective band-like loss of elastic fibers in the middermis (see Fig. 67-3B). There is preservation of normal elastic tissue in the superficial papillary dermis above, in the reticular dermis below, and along adjacent hair follicles. Electron microscopy studies have shown phagocytosis of normal as well as degenerated elastic fiber tissue by macrophages.20

MDE must be differentiated from the other common disorders of elastic tissue.

Solar elastosis differs by its onset in an older age group, location in only sun-exposed areas, yellowish color, and coarser wrinkling, as well as by hyperplasia and abnormalities of elastic fibers and basophilic degeneration of the collagen in the papillary dermis.

Anetoderma is characterized clinically by smaller soft macules and papules instead of diffuse wrinkling, and histologically by elastolysis that can occur in any layer of the dermis.

Perifollicular elastolysis differs by a selective and almost complete loss of elastic fibers surrounding hair follicles compared with preservation of elastic fibers around follicles in MDE. Elastase-producing Staphylococcus epidermidis was found in the hair follicles and is the presumed etiology of this condition.21

Postinflammatory elastolysis and cutis laxa were originally described in young girls of African descent. An inflammatory phase, consisting of indurated plaques or urticaria, malaise, and fever, preceded the diffuse wrinkling, atrophy, and severe disfigurement. Insect bites may be the trigger for the initial inflammatory lesions.22

Treatment

There is no known effective treatment for MDE. Sunscreens, colchicine, and topical retinoic acid have been tried without good success.15,16

Striae are very common and usually develop between the ages of 5 and 50 years.

They occur about twice as frequently in women as in men. They commonly develop during puberty, with an overall incidence of 25%–35%,23,24 or during pregnancy, with an incidence of 77%.25

The factors leading to the development of striae have not been fully elucidated. Striae distensae are the results of breaks in the connective tissue, resulting in dermal atrophy. Many factors, including hormones (particularly corticosteroids), mechanical stress, and genetic predisposition, appear to play a role.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree