1 Anatomy of the head and neck

Synopsis

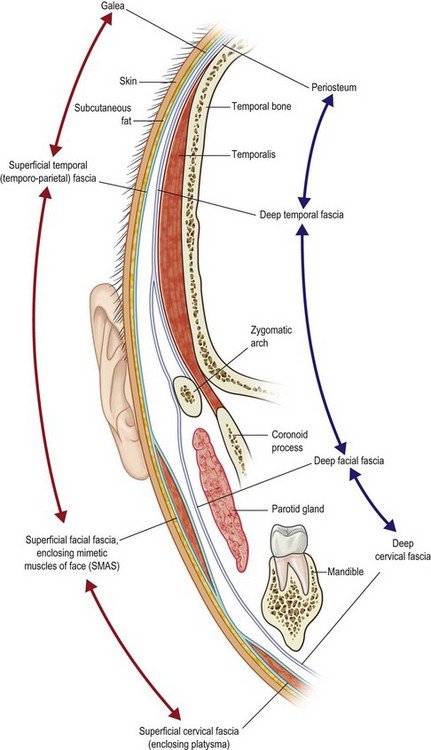

The superficial fascial layer of the face and neck is formed of the superficial cervical fascia (enclosing the platysma), the superficial facial fascia (also referred to as the SMAS), the superficial temporal fascia (often called the temporoparietal fasica), and the galea.

The superficial fascial layer of the face and neck is formed of the superficial cervical fascia (enclosing the platysma), the superficial facial fascia (also referred to as the SMAS), the superficial temporal fascia (often called the temporoparietal fasica), and the galea.

The deep fascial layer of the face and neck is formed of the deep cervical fascia (or the general investing fascia of the neck), the deep facial fascia (also known as the parotidomasseteric fascia), and the deep temporal fascia. The deep temporal fascia is continuous with the periosteum of the skull.

The deep fascial layer of the face and neck is formed of the deep cervical fascia (or the general investing fascia of the neck), the deep facial fascia (also known as the parotidomasseteric fascia), and the deep temporal fascia. The deep temporal fascia is continuous with the periosteum of the skull.

The deep temporal fascia splits into two layers at the level of the superior orbital rim. The two layers insert into the superficial and deep surfaces of the zygomatic arch.

The deep temporal fascia splits into two layers at the level of the superior orbital rim. The two layers insert into the superficial and deep surfaces of the zygomatic arch.

The facial nerve is initially deep to the deep fascia, eventually penetrating it towards the superficial fascia. The fat and connective tissue filling the space between the superficial temporal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is a subject of significant debate. Its importance stems from the temporal branch of the facial nerve crossing from deep to superficial in this layer.

The facial nerve is initially deep to the deep fascia, eventually penetrating it towards the superficial fascia. The fat and connective tissue filling the space between the superficial temporal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is a subject of significant debate. Its importance stems from the temporal branch of the facial nerve crossing from deep to superficial in this layer.

Most surgeons believe that it is the superficial temporal fat pad that fills this space. Others believe there is a distinct fascial layer in this region, named the parotidomasseteric fascia.

Most surgeons believe that it is the superficial temporal fat pad that fills this space. Others believe there is a distinct fascial layer in this region, named the parotidomasseteric fascia.

The facial nerve is at significant risk of injury in the area right above the zygomatic arch.

The facial nerve is at significant risk of injury in the area right above the zygomatic arch.

Pitanguy’s line is an accurate description of the course of the largest and more significant branch of the temporal division of the facial nerve.

Pitanguy’s line is an accurate description of the course of the largest and more significant branch of the temporal division of the facial nerve.

The marginal mandibular nerve can be located above or below the level of the mandible. It is usually located between the platysma and the deep cervical fascia, and is always superficial to the facial vessels.

The marginal mandibular nerve can be located above or below the level of the mandible. It is usually located between the platysma and the deep cervical fascia, and is always superficial to the facial vessels.

There are multiple fat pads in the face. They can be superficial to the SMAS, between the SMAS and the deep fascia, or deep to the deep fascia.

There are multiple fat pads in the face. They can be superficial to the SMAS, between the SMAS and the deep fascia, or deep to the deep fascia.

Knowledge of the sensory nerves is important, especially with our current understanding of their role in migraine headaches.

Knowledge of the sensory nerves is important, especially with our current understanding of their role in migraine headaches.

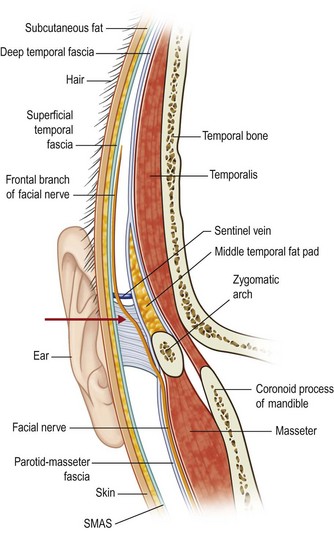

The fascial planes of the head and neck and the facial nerve

A peculiar feature of the anatomy of the head and neck is the concentric arrangement of the facial soft tissues in layers. These layers have different names and characteristics from one area of the head and neck to the other, but they maintain their continuity across boundaries (Fig. 1.1). Unfortunately, inconsistent nomenclature has been used to describe these layers leading to significant confusion among readers. The facial nerve usually passes in defined planes in between these layers, crossing from one layer to the other only in specific well described zones. Knowledge of these planes and their relation to the facial nerve is vital if plastic surgeons are to safely access the soft tissues and bony structures of the head and neck.1,2 In the following discussion, we will not only describe the anatomy and nomenclature of these layers as mostly agreed upon, but also try to elucidate the sources of deliberation and confusion in describing this crucial anatomy.3

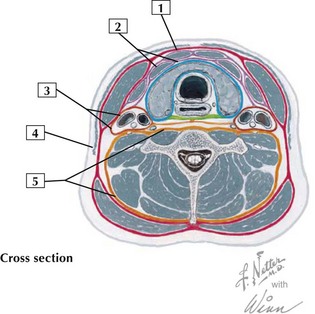

The neck, cheek (lower face), temple and the scalp are arbitrarily divided by the lower border of the mandible, the zygomatic arch and the temporal line, respectively. In general, there are two layers of fascia, a superficial and deep, which cover these regions and extend over other structures, such as the eyelid and the nose (Fig. 1.1).

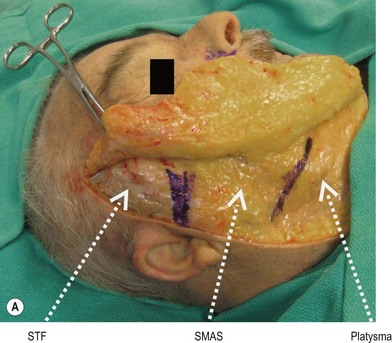

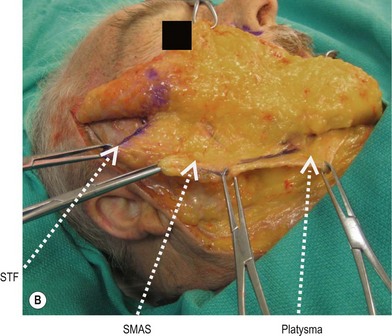

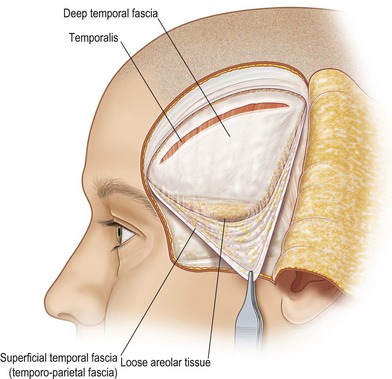

The superficial layer of fascia is formed by the superficial cervical fascia (platysma), the superficial facial fascia (SMAS), the superficial temporal fascia (temporoparietal fascia) and the galea aponeurotica (Figs 1.1, 1.2). To be more precise, this superficial fascia splits to enclose many of the facial muscles. This is a consistent pattern seen all over the head and neck region; e.g. the superficial cervical fascia splits into a deep and superficial layer to enclose the platysma, the superficial facial fascia splits to enclose the midfacial muscles, and the galea splits to enclose the frontalis. The two layers of the superficial fascia then rejoin at the other end of the muscle, before splitting again to enclose the next muscle and so on.

The deep layer of fascia is formed by the deep cervical fascia, the deep facial fascia (parotidomasseteric fascia), the deep temporal fascia and the periosteum. This layer is superficial to the muscles of mastication, the salivary glands and the main neurovascular structures (Figs 1.1, 1.2). Over bony areas, such as the skull and the zygomatic arch, this deep fascia is inseparable from the periosteum.

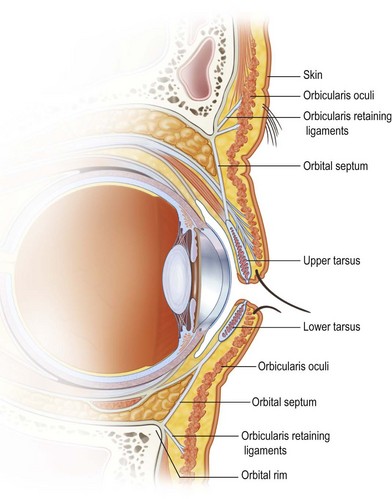

The facial fat pads are localized collection of fat present deep to the superficial layer of fascia. These are separate anatomically and histologically from the subcutaneous fat present between the skin and the superficial fascia. These fat pads include the superficial temporal fat pad, the galeal fat pad, suborbicularis oculi fat pad (SOOF), the retro-orbicularis oculi fat pad (ROOF), and the preseptal fat of the eyelids. Deep to the deep fascia are several other fat pads; the deep temporal fat pads, the buccal fat pads, and the postseptal fat pads of the eyelids.4

The fascia in the face

The first layer the surgeon encounters in the face deep to the skin and its associated subcutaneous fat is the SMAS (Superficial Musculo-Aponeurotic System) (Figs 1.1, 1.2).5 The SMAS varies in thickness and composition between individuals and from one area to another, and it can be fatty, fibrous, or muscular.6 The muscles of facial expression, e.g. orbicularis oculi, oris, zygomaticus major and minor, frontalis, platysma are enclosed by (or form part of) the SMAS. The SMAS is often referred to as the superficial facial fascia. In reality, the superficial facial fascia covers the superficial and deep surfaces of the muscles. However, these layers are hard to separate intraoperatively (except in certain areas such as the neck). Dissection superficial to the superficial facial fascia (just under the skin) will generally avoid injury to the underlying facial nerve. However, such dissection can compromise the blood supply of the overlying skin flaps. Often, the surgeon can safely maintain this superficial fascia in the lower face and neck (whether it is the platysma or the SMAS) with the skin, allowing a secure double layer closure and maintaining skin vascularity (e.g. during a neck dissection). In the anterior (medial) face, the facial nerve branches become more superficial just under or within the SMAS layer.

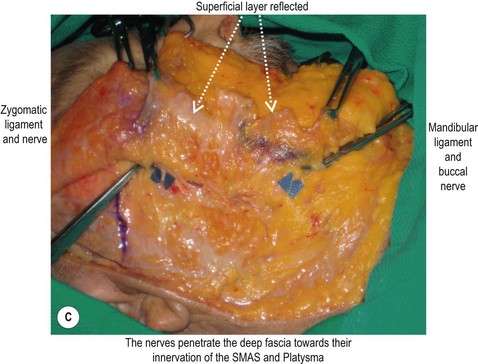

The next layer in the face is the deep facial fascia, which is also known as the parotidomasseteric fascia (Figs 1.1, 1.2). Over the parotid gland, this layer is adherent to the capsule of the gland. The facial nerve is initially (i.e. right after is exits the parotid gland) deep to the deep facial fascia. Most of the muscles of facial expression are superficial to the planes of the nerve. The nerve branches pierce the deep fascia to innervate the muscles from their deep surface, with the exception of the mentalis, levator anguli oris and the buccinators (Fig. 1.2). These three muscles are deep to the facial nerve and are thus innervated on their superficial surface.

The fascia in the temporal region

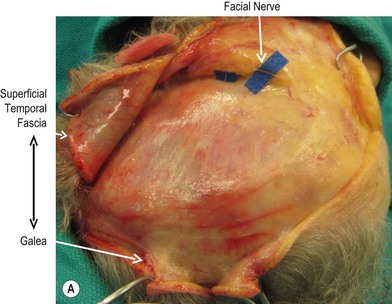

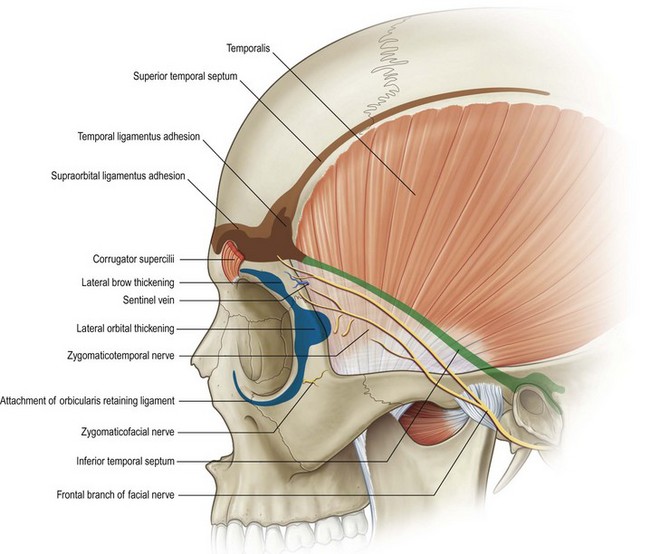

The cheek and lower face are separated from the temporal region by the zygomatic arch. There are two layers of fascia in the temporal region (below the skull temporal lines); the superficial temporal fascia (also known as the temporoparietal fascia, TPF) and the deep temporal fascia (Figs 1.3, 1.4A).7–9 The deep temporal fascia lies on the superficial surface of the temporalis muscle. Between the superficial and deep temporal fascia is a loose areolar plane that is relatively avascular and easily dissected. However, the frontal branch of the facial nerve is within or directly beneath the superficial temporal fascia (Fig. 1.4A).5 Therefore, dissection in this plane should be strictly on the deep temporal fascia, which can be identified by its bright white color and sturdy texture. To ensure that the surgeon is in the right plane, he can attempt to grasp the areolar tissues over the deep temporal fascia using an Adson forceps; if in the right plane, one will not catch any tissue. Once deep enough and right on the deep temporal fascia, dissection can proceed quickly using a periosteal elevator hugging the tough deep temporal fascia (Fig. 1.5).

In the region right above the zygomatic arch the space between the superficial TPF and the deep temporal fascia (sometimes referred to as the subaponeurotic space) and the fat/fascia it contains is both a debatable and an important subject (Fig. 1.4). Its importance stems from the facial nerve crossing this space from deep to superficial right above the zygomatic arch. A third layer of fascia has been described in this space (between the superficial and deep layers), and is referred to as the parotido-temporal fascia, the subgaleal fascia, or the innominate fascia.10,11 The term “fascial layer” is used loosely, as there is no general consensus as to how thick connective tissue must be before it can be considered a “fascial layer”. What some authors refer to as “loose connective tissue” may be called a “fascial layer” or a “fat pad” by others. Our own cadaver dissection showed that this third fascial layer could often be identified. It extends for a short distance above and below the arch. Directly superficial to the arch, the facial nerve is deep to this layer, piercing it to become more superficial 1–2 cm cephalad to the arch (see below).

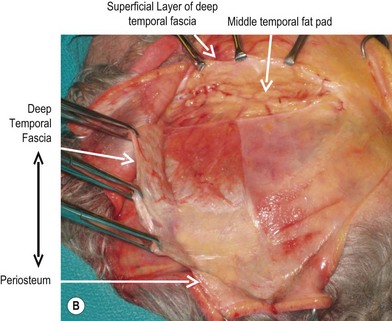

Above the zygomatic arch and at the same horizontal level as the superior orbital rim, the deep temporal fascia splits into two layers; the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia (sometimes referred to as the middle temporal fascia, intermediate fascia, or the innominate fascia) and the deep layer of the deep temporal fascia (Fig. 1.3).7 The deep and superficial layers of the deep temporal fascia attach to the superficial and deep surfaces of the zygomatic arch. There are three fat pads in this region.7,12 The superficial fat pad is located between the superficial temporal fascia and superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia, and as described above, is analogous with the parotido-temporal fascia, subgaleal fascia, and/or the loose connective tissue between the superficial and deep temporal fascia. The middle fat pad is located directly above the zygomatic arch between the superficial and deep layers of the deep temporal fascia. Finally, the deep fat pad (also know as the buccal fat pad) is deep to the deep layer of the deep temporal fascia, superficial to the temporalis muscles and extends deep to the zygomatic arch. It is considered an extension of the buccal fat pad.

Most of the controversy in describing the fascial layers in the temporal region arises from confusing the superficial temporal fascia with the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia. This is very significant since the facial nerve is deep to or within the former and superficial to the latter. The second baffling point is the location of the deep temporal fascia superficial to the temporalis muscle. There is another fascial layer on the deep surface of the muscle; this is not the deep temporal fascia and is of little significance from a surgical standpoint. The final controversy is what exactly is the innominate fascia? This term is often used to describe the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia above the arch. Other surgeons reserve the term to the areolar tissue between the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia and the superficial temporal fascia (i.e., the innominate fascia can be synonymous with the parotidotemporal fascia or subgaleal fascia or the superfical temporal fat pad).13

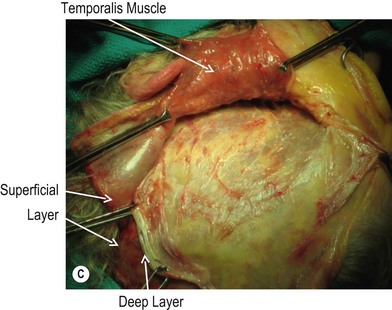

The plane of dissection in the temporal region depends on the goal of the surgery (Fig. 1.4). In general, the surgeon should avoid the superficial temporal fascia as it harbors the frontal branch of the facial nerve. During surgery to expose the orbital rims and the forehead musculature, the dissection plane is between the superficial temporal fascia and deep temporal fascia (Fig. 1.4A). To expose the arch, the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is divided and dissection proceeds between it and the middle fat pad (the superficial layer of deep temporal fascia will act as an extra layer protecting the nerve) (Fig. 1.4B). Finally, when a coronal approach is used, but the arch does not need to be exposed, dissection can proceed deep to the temporalis muscles, elevating them with the coronal flap (Fig. 1.4B). Using this avascular plane avoids potential traction or injury to the frontal nerve, and ensures good aesthetic results as it prevents possible fat atrophy or retraction of the temporalis muscle.

While the fascial layers in the temporal region are well described, there is more debate and variability of the anatomy of the fascial layers and the facial nerve directly superficial to the arch.12,14,15 The superficial facial fascia (SMAS) is continuous with the TPF, but it is not clear if the deep facial and deep temporal fasciae are continuous to each other or attach and arise from the periosteum of the arch separately. In addition, the thickness of the soft tissues from the periosteum to skin is minimal and the tissues are tightly adherent, making identification of the facial planes and the facial nerve hazardous in this region.16 The frontal branch of the facial nerve pierces the deep temporal fascia to become more superficial near the vicinity of the upper border of the arch, and this area constitutes one of the danger zones of the face (see below).

The fascia in the neck

The nomenclature used to describe the different fascial layers in the neck also creates significant confusion. There are two different fascias in the neck: the superficial and the deep (Figs 1.3, 1.6). The latter is composed of three different layers: (1) the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, also known the general investing layer of deep cervical fascia; (2) the middle layer, commonly named the pretracheal fascia; and (3) the deep layer, or the prevertebral fascia (Figs 1.3, 1.6). The pretracheal fascia encircles the trachea, thyroid and the oesophagus, while the prevertebral fascia encloses the prevertebral muscles and forms the floor of the posterior triangle of the neck. For practical purposes, it is the superficial cervical fascia and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia that the plastic surgeon encounters.17,18

The superficial cervical fascia encloses the platysma muscle and is closely associated with the subcutaneous adipose tissue. The platysma muscle and its surrounding superficial cervical fascia represent the continuation of the SMAS into the neck. In general, when skin flaps are raised in the neck, the platysma muscle is maintained with the skin to enhance its blood supply (e.g. during neck dissections). However, in necklifts the skin is raised off the platysma to allow platysmal shaping and skin redraping. Tissue expanders placed in the neck could be placed either deep or superficial to the platysma. Placing them superficially will create thinner flaps that are more suitable for facial resurfacing, while placing them deeper allows a more secure coverage of the expander.19,20

Retaining ligaments and adhesions of the face

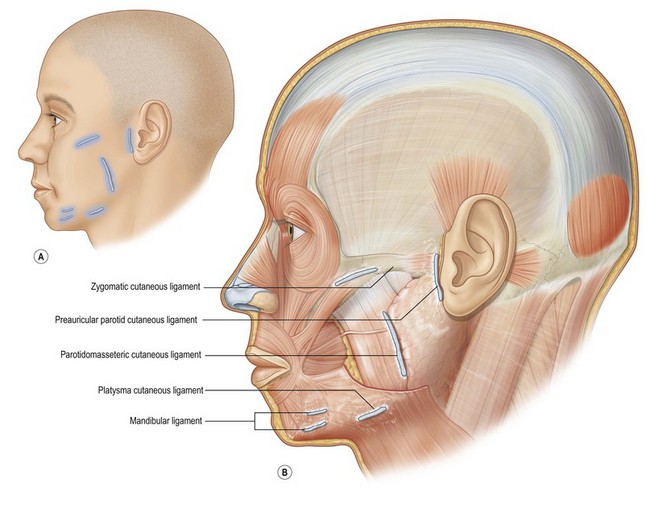

Various terms have been used to describe these ligamentous attachments. Moss et al. classified them into ligaments (connecting deep fascia/periosteum to the dermis), adhesions (fibrous attachments between the deep and the superficial fascia), and septi (fibrous wall between layers).21

In the periorbital and temporal region, various ligaments and adhesions have been described with numerous names given to each (Fig. 1.7). Along the skull temporal line lies temporal line of fusion, also know as the superior temporal septum.21 This represents the coalition of the temporal fascia with the skull periosteum. These adhesions end as the temporal ligamentous adhesions (TLA) at the lateral third of the eyebrow. The TLA measure approximately 20 mm in height and 15 mm in width, and begins 10 mm cephalad to the superior orbital rim. Both the temporal line of fusion and the TLA are sometimes referred to collectively as temporal adhesions. The inferior temporal septum extends posteriorly and inferiorly from the TLA on the surface of the deep temporal fascia towards the upper border of the zygoma. The supraorbital ligamentous adhesions extend from the TLA medially along the eyebrow.

The orbicularis retaining ligament (ORL) lies along the superior, lateral and inferior rims of the orbit, extending from the periosteum just outside the orbital rim to the deep surface of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Fig. 1.8).22,23 This ligament serves to anchor the orbicularis oculi muscle to the orbital rims. The orbicularis oculi muscle attaches directly to the bone from the anterior lacrimal crest to the level of the medial limbus. At this level the ORL replaces the bony origin of the muscle, continuing laterally around the orbit. Initially short, it reaches its maximum length centrally near the lateral limbus.24 It then begins to diminish in length laterally, until it finally blends with the lateral orbital thickening (LOT). The LOT is a condensation of the superficial and deep fascia on the frontal process of the zygoma and the adjacent deep temporal fascia. The ORL and the orbital septum both attach to the arcus marginalis, a thickening of the periosteum of the orbital rims.23 The ORL is also referred to as the periorbital septum and, in its inferior portion, as the orbitomalar ligament. The ORL ligament attaches to the undersurface of the orbicularis oculi muscle at the junction of the pretarsal and orbital parts.

In the midface, the retaining ligaments have been divided into direct, or osteocutaneous ligaments, and indirect ligaments. Direct ligaments run directly from the periosteum to the dermis, and include the zygomatic and mandibular ligaments. Indirect ligaments represent a coalescence between the superficial and deep fascia, and include the parotid and the masseteric cutaneus ligaments (Fig. 1.9, and see Fig. 1.2C). The retaining ligaments indirectly fix the mobile skin and its intimately related superficial fascia (SMAS), to the relatively immobile deep fascia and underlying structures (masseter and parotid).

Fig. 1.9 The retaining ligaments of the face.

(Reproduced with permission from Gray’s Anatomy 40e, Standring S (ed), Churchill Livingstone, London, 2008.)

The zygomatic and the masseteric ligaments together form and inverted L, with the angle of the L formed by the major zygomatic ligaments (Fig. 1.9, and see Fig. 1.2C). These ligaments are typically around 3 mm wide and are located 4.5 cm in front of the tragus and 5–9 mm behind the zygomaticus minor muscle.25–28 Anterior to this main ligament are multiple other bundles that form the horizontal limb of the inverted L. The vertical limb of the L is formed by the masseteric ligaments, which are stronger near their upper end (at the zygomatic ligaments), and extend along the entire anterior border of the masseter as far as the mandibular border.5,29 The parotid ligaments, also referred to as preauricular ligaments, represent another area of firm adherence between the superficial and deep fascia.25,27,28 The mandibular ligaments originate from the parasymphysial region of the mandible around 1 cm above the lower mandibular border.27,28 There are several descriptions of other retaining ligaments in the face, most notably the mandibular septum and the orbital retaining septum.30,23

The prezygomatic space

The prezygomatic space is a glide plane space overlying the body of the zygoma, deep to the orbicularis oculi and the suborbicularis fat (Fig. 1.8).31 Its floor is formed by a fascial layer covering the body of the zygoma and the lip elevator muscle (namely the zygomaticus major, zygomaticus minor and the levator labii superioris). This fascial layer extends caudally over the muscles, gradually becoming thinner and allowing the muscle to be more discernible. The superior boundary of the prezygomatic space is the orbicularis retaining ligament, which separates it from the preseptal space. The more rigid inferior boundary is formed by the reflection of the fascia covering the floor as it curves superficially to blend with the fascia on the undersurface of the orbicularis oculi. This inferior boundary is further reinforced by the zygomatic retaining ligaments. Medially, the space is closed by the origins of the levator labii and the orbicular oculi muscle from the medial orbital rim. Finally, the lateral boundary is formed superiorly by the LOT over the frontal process of the zygoma and more inferiorly by the zygomatic ligaments.32 The facial nerve branches cross in the roof of (i.e. superficial to) this space. The only structure traversing the pre zygomatic space is the zygomatico facial nerve, emerging from its foramen located just caudal to ORL.

The malar fat pad

This is a subcutaneous pad of fat superficial to the SMAS (which encloses the orbicularis oculi) in the cheek.33 This pad is triangular in shape, with its base at the nasolabial crease and its apex more laterally towards the body of the zygoma. Elevation of the malar fat pad is important for facial rejuvenation and in facial palsy.

The buccal fat pad

The buccal fat pad is an underappreciated factor in post traumatic facial deformities and senile aging, and is frequently overlooked as a flap or graft donor site.34,35 Senile laxity of the fascia allows the fat to prolapse laterally, contributing to the square appearance of the face.36 With many traumatic injuries the fat herniates, either superficially, towards the oral mucosa, or even into the maxillary sinus.24,37–39 This fat is anatomically and histologically distinct from the subcutaneous fat. It is voluminous in infants to prevent indrawing of the cheek during suckling, and gradually decreases in size with age.40 It functions to fill the glide planes between the muscles of mastication.

It is usually described as being formed of a central body and four extensions, the buccal, pterygoid and superficial and deep temporal. The body is located on the periosteum of the posterior maxilla (surrounding the branches of the internal maxillary artery) overlying the buccinator muscle and extends forwards in the vestibule of the mouth to the level of the maxillary second molar. The buccal extension is the most superficial, extending along the anterior border of the masseter around the parotid duct. Both the body and the buccal extension are superficial to the buccinator and deep to the deep facial fascia (parotido-masseteric fascia), and are intimately related to the facial nerve branches and the parotid duct. The buccal extension is in the same plane as the facial artery, which marks its anterior boundary. The pterygoid extension passes backwards and downwards deep to the mandibular ramus to surround the pterygoid muscles. The deep temporal extension passes superiorly between the temporalis and the zygomatic arch. The superficial temporal extension is actually totally separate from the main body, and lies between the two layers of the temporal fascia above the zygomatic arch.41

The facial nerve

During most facial plastic surgeries, whether congenital, reconstructive or aesthetic, there are one or more branches of the facial nerve that are at risk for injury. Although there is abundant literature on the anatomy of the facial nerve branches, the majority of publications describe two-dimensional anatomy, depicting the trajectory of the nerve and its surface anatomy in relation to anatomic landpoints (see Fig. 1.3).9,16,42–49 However, it is the third dimension, the depth of the facial nerve in relation to the layers of the face that is most relevant to the practicing surgeon. In spite of the significant variability in the branching patterns, the facial nerve consistently passes in defined planes, crossing from one plane to another in certain zones.1 It is in these “danger zones” that dissection should be avoided or done carefully. In the rest of the face, the dissection can proceed relatively quickly by adhering to a certain plane, either superficial or deep to the plane of the nerve.

1. If the tragal cartilage is followed to its deep end, it terminates in a point. The nerve is 1 cm deep and inferior to this “tragal pointer”. There is an avascular plane right on the anterior surface of the tragus that allows a safe and quick dissection to this tragal pointer.

2. By following the posterior belly of the digastric posteriorly, the nerve is found passing laterally immediately deep to the upper border of the posterior end of the muscle.

3. If the anterior border of the mastoid process is traced superiorly, if forms an angle with the tympanic bone. The nerve bisects the angle formed between these two bones (at the tympanomastoid suture).

4. By feeling the styloid process in between the mastoid bone and the posterior border of the mandible. The nerve is just lateral to this process.

5. By following the terminal branches of the nerve proximally.

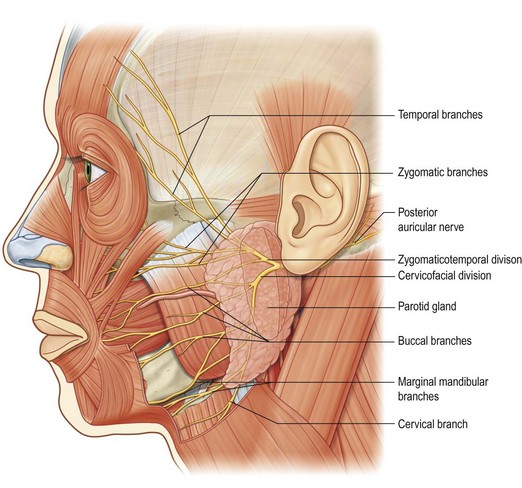

The nerve passes forwards and downwards to pierce the parotid gland. In the parotid gland the nerve divides into the zygomaticotemporal and the cervicofacial divisions, which in turn divide into the five terminal branches of the facial nerve: frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical (Fig. 1.10). However, the zygomatic and buccal branches show significant variability in their location and branching patterns as well as a significant overlap in the muscles they innervate – they are sometimes grouped together and referred to as “zygomaticobuccal”. The temporal and the mandibular branches are perhaps at the highest risk for iatrogenic injury, especially that the muscles they innervate show little if any cross innervation, making injury to these branches much more noticeable.

Frontal (temporal) branch

This consists of 3–4 branches that innervate the orbicularis oculi muscle, the corrugators and the frontalis muscle. Several anatomic landmarks are used to describe their surface anatomy. The most common description is Pitanguy’s line; extending from 0.5 cm below the tragus to a point 1 cm above the lateral edge of the eyebrow (or 1 cm lateral to the lateral canthus).50,9 Ramirez described the nerve as crossing the zygomatic arch 4 cm behind the lateral canthus.51 However, other surgeons describe the area spanning the middle two thirds of the arch as the territory of the nerve. Gosain et al. found frontal nerve branches are found at the lower border of the zygomatic arch between 10 mm anterior to external auditory meatus and 19 mm posterior to the lateral orbital rim.16 Finally, Zani et al. in 300 cadaver dissections reported that the nerve is in a region limited by two straight diverging lines; the first line from the upper tragus border to the most cephalic wrinkle of the frontal region, and the second line from the lower tragus border to the most caudal wrinkle of the frontal region.45 Although there is no connection between the frontal nerve and other branches of the facial nerve, there are connections within the frontal branches themselves.16 In addition, the more posterior divisions of the frontal nerve may be less clinically significant than the anterior branches, the injury of which will lead to noticeable brow deformities.16 A line from the tragus to 1 cm above the lateral eyebrow or 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral canthus seems to be a fairly accurate marking of the largest branch of the frontal nerve.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree