Chapter 19 Anatomy of the abdominal wall and aesthetic classification

• Subcutaneous and myoaponeurotic abdominal deformities must be identified.

• Surgery must be planned accordingly to the patient’s deformity, diagnosed either pre- or intraoperatively.

• Look for congenital rectus diastasis intraoperatively to avoid recurrence of rectus diastasis.

• If there is still myoaponeurotic laxity after the approximation of the rectus edges, plication of the external oblique aponeurosis should be performed.

• Supraumbilical undermining should be performed at the minimum width of the supraumbilical area in order to preserve the perforator arteries of the rectus muscle.

Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall and its Surgical Implications on Abdominoplasty

Subcutaneous Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The subcutaneous tissue of the anterior abdomen is divided into two layers: the superficial (areolar) and the deep (lamellar) layer. The superficial fascia, also called Scarpa’s fascia, separates these two planes. Adipose tissue is thick and dense in the superficial layer, which is evenly distributed over the whole abdomen. The fat tissue in the deep layer is loose. In the infraumbilical area, these layers are very well defined, whereas in the supraumbilical region this separation is not very clear.1 In the infraumbilical area there is a wide variety of thickness of adipose tissue depending on the patient’s weight. It is important to know this anatomy when there is a difference in subcutaneous thickness between the flap and the area inferiorly to the abdominal incision. In such cases, the removal of the lamellar layer deep to Scarpa’s fascia can be a good option. This removal can be performed up to the umbilicus2 or in all the extension of the abdominal flap.

Blood Supply of the Abdominal Wall

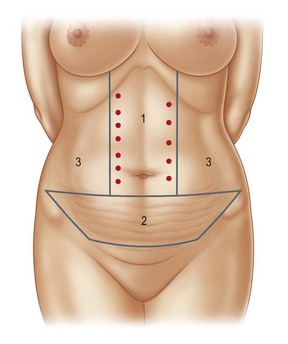

The abdominal skin is supplied by a subdermal arterial plexus originated from a complex network of superficial vessels. Most of these vessels are supplied by the superficial epigastric artery, the superficial circumflex iliac artery, and also from perforators of the superior and inferior epigastric artery. Superficial branches of the intercostal arteries and lumbar branches are also part of this arterial supply.3 When describing the arterial anatomy of the abdominal wall, it is important to define the zones of blood supply which will have an important role in necrosis prevention. There are three areas of blood supply4 that have been described from the perspective of the surgeon. Knowledge of these areas guides the surgeon during abdominal flap undermining (Fig. 19.1). Zone I is the most important area and should be preserved as much as possible during flap undermining. It is located at the supraumbilical region, in which the main arterial flow comes from the perforators of the deep superior epigastric artery. By performing a more localized undermining, surgeons can preserve some of these arteries.

Sensitive Innervation of the Abdominal Wall

The intercostal, subcostal, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves are responsible for the sensitivity innervation of the anterior abdominal wall.5 The intercostal nerves are branches originating from T7 to T11. The subcostal nerves originate from T12 whereas the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originate from L1. Branches from T7 to T9 innervate the supraumbilical area, T10 innervates the periumbilical area and the branches originating from T12 and L1 provide innervation to the infraumbilical area.

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system of the subcutaneous tissue of the supraumbilical area drains to the axillary lymph nodes, whereas the infraumbilical system drains to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.6 The periumbilical area may also drain to deep abdominal periaortal lymph nodes. Inefficient lymphatic drainage can be one of the causes of seroma.

Myoaponeurotic Anatomy

After describing the rectus sheath anatomy, it is easy to understand why the plication of the anterior rectus sheath is a reliable procedure. As there is a dense attachment between the anterior sheath and the muscle, the plication will effectively bring these muscles together.7–11 However, if these muscles present a lateral origin in the rib cage, recurrence of the plication may occur, as repeated muscle contraction may lead to suture disruption in the upper abdomen.12

The muscles of the flank of the abdomen are the external oblique, internal oblique, and the transverse muscle. The fibers of the oblique muscles are perpendicular to the internal oblique fibers and there is a loose connective tissue between them. This is taken into account if a plication of the external oblique aponeurosis is performed; there is a real decrease of the distance between the origin and insertion of the muscle, thus promoting a more efficient contraction of the muscle and a positive cosmetic effect. It is also important to stress that the arterial supply to the external oblique muscle and its innervation penetrates the muscle laterally to the anterior axillary line.13 Therefore, when the advancement of the external oblique muscle is performed, the undermining on the loose connective tissue above the internal oblique muscle can be performed safely laterally to the anterior axillary line.

The Umbilicus

The attractive umbilicus should have a central depression, a superior skin hood and should also be more vertically shaped. The most accepted position of the umbilicus is at the level above the iliac crests.14 It is not an easy task to achieve all these goals when performing an abdominoplasty. To obtain an attractive umbilicus will depend on the design of the incisions used in the skin and in the umbilicus, on the skin closure tension, and on the abdominal level chosen to place the umbilicus.

Preoperative Preparation

Candidates for abdominoplasty should have a stable weight by the time of the operation to obtain the best possible result. If the patient is overweight and there is some difficulty advancing the flap on the pinch test, weight loss will benefit the patient’s result. Women should be past all their pregnancies before abdominoplasty; however, if a patient gets pregnant after this operation, there is a chance that the musculoaponeurotic deformity will not recur.9 A compressive abdominal garment is used for 1 week before the surgery to adapt the abdominal wall to the myoaponeurotic correction. Smoking and birth control medication should be discontinued for at least 15 days preoperatively.

Diagnosis of the Abdominal Wall Deformities and Surgical Technique

Esthetic Classification of Abdominal Wall Deformities

Deformities of the abdominal wall vary. Each individual will present a specific deformity, depending on inherited characteristics, age and – for women – previous pregnancies. Therefore, a different surgical solution is applicable to each of the abdominal deformities. So that surgeons can easily understand which technique would be more suitable for correcting a specific deformity, two classifications have been described. The first one evaluates excess skin and subcutaneous tissue,15 whereas the other evaluates malpositioning and laxity of the myoaponeurotic layer.16 For each degree of deformity, a specific technique is suggested. Therefore, a combination of the methods described on both classifications can be used, depending on the patient’s deformity.

Classification Based on the Excess Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

In this classification, deformities are categorized into four different types: 0, I, II and III.

Type 0

Deformity – these patients present an abdominal deformity exclusively due to excessive subcutaneous tissue. There is no excess skin, although some patients may present a little excess skin caused by previous pregnancy or weight loss.

Management – correction of the deformity is achieved by suction lipectomy only (Fig. 19.2).

Type I

Deformity – these patients present little or mild excess skin and a high positioned umbilicus.

Management – an incision usually slightly smaller than those used on classical abdominoplasties is performed tangentially to the suprapubic hairline. The abdominal flap is elevated, exposing the linea alba from the pubis to the xiphoid process. The umbilical pedicle is sectioned and the umbilical skin is maintained with the abdominal flap. The muscular defect is corrected and the excess skin is resected on an area marked with the shape of an Indian canoe. The umbilicus is reattached in the aponeurosis not lower than 2 or 3 cm below its original position (Fig. 19.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree