Anatomy and Approach in Dermatologic Surgery: Introduction

|

Dermatologic surgery has rapidly become a cornerstone of the practice of dermatology. Factors such as the epidemic of skin cancer, the interest in maintaining a youthful appearance for an aging population that is living longer, and the financial pressures to perform surgery in less expensive outpatient settings have led to an increase in the number of surgical procedures performed in dermatologic practice.

Anatomy

Anatomy is often called the language of surgery.1,2 Knowledge of anatomy is critical for a number of reasons, including communicating precisely with colleagues, performing efficient and safe procedures, obtaining optimal functional and aesthetic reconstruction, understanding the lymphatic drainage, and anticipating the metastatic spread of malignancies. As the majority of cosmetic and surgical procedures are performed on the face, and because of its complexity, this chapter focuses on the superficial cutaneous anatomy of this critical region.

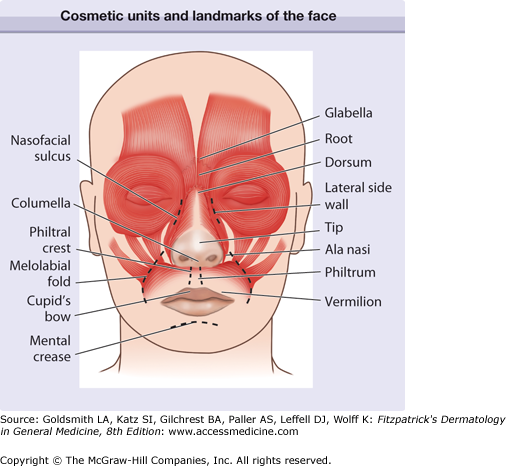

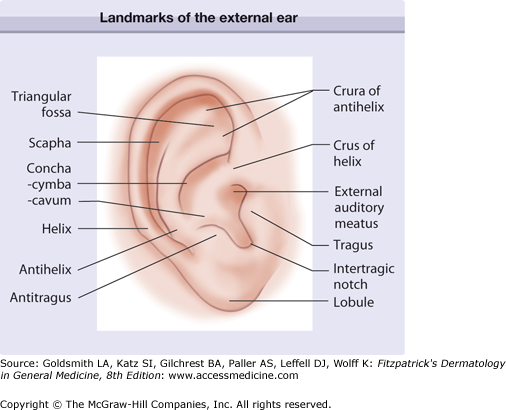

Landmarks and cosmetic units help localize areas of the face accurately and precisely for purposes of communication with colleagues and to perform the surgery itself. For instance, it is more helpful to describe a lesion on the face if it is said to be located on the “left nasal sidewall” versus left nose or “right triangular fossa” versus right ear. Cosmetic units are zones of tissue that share cutaneous features such as color, texture, pilosebaceous quality, pore size, and degree of actinic exposure. These cosmetic units are demarcated by junction lines that can be discrete (eyebrows) or subtle (nasofacial sulcus). Cosmetic units can also be further divided into subunits. Because of the tissue similarity, it is often best to reconstruct a surgical defect within a cosmetic unit or subunit or borrow tissue from nearby units. In addition, scar lines can be hidden easily in junction lines between the cosmetic units. The more complex regions of the face that have multiple subunits include the nose, ears, and lips (Figs. 242-1 and 242-2).

The subunits of the nose include the glabella (the area between the eyebrows), the root (the deep sulcus below the glabella and uppermost portion of the nose), dorsum or bridge (the area overlying the nasal bone), lateral side walls (the sides of the nose), nasal tip, the nasal ala (the nostril), alar groove and nasolabial crease (the grooves that demarcate the alae superiorly from the lateral nasal sidewall and alae inferiorly from the lip, respectively), and the columella (the mobile linear structure separating the alae inferiorly) (see Fig. 242-1).

The lateral surface of the ear is rimmed by the helix, a curved cartilaginous structure that begins at the crus just above the external auditory canal and continues around the ear to end at the fleshy lobule. The central concavity within which the external auditory meatus lies is the concha. The concha is divided by the crus of the helix into a superior portion, the cymba, and an inferior portion, the cavum. The posterior border of the concha is formed by another cartilaginous structure called the antihelix. Superiorly, the antihelix originates from two legs (crus is Latin for leg): (1) the superior crus and (2) inferior crus. The region between the crura is referred to as the triangular fossa. The groove between the helix and antihelix is the scaphoid fossa. The triangulated cartilaginous structure just anterior to the auditory canal is called the tragus, and just posterior to this is the triangulated end of the antihelix, referred to as the antitragus. The inferior region between the tragus and antitragus is the intertragic notch (see Fig. 242-2).

The cutaneous upper lip has a concave depression in the center, called the philtrum, which is bounded by two ridges, the philtral crests. There is a prominent crease, the mental crease, which divides the cutaneous lower lip from the chin. The boundary between the red mucosal surface of the lips and the cutaneous surface is called the vermillion border. The raised contoured area of the inferior portion of the philtrum is a critical aesthetic landmark known as the Cupid’s bow (see Fig. 242-1).

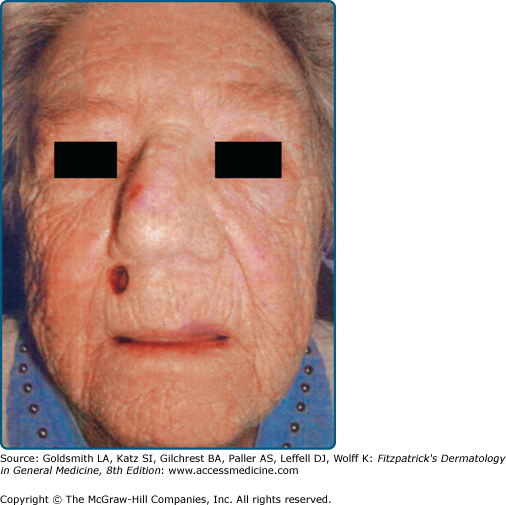

Relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) are another characteristic of the face that help guide surgical reconstruction and allow the structural camouflage of scar lines. RSTLs are creases on the face that form over time due to factors such as loss of elastic tissue tone, lengthening of the collagenous fibrous septae that connect the dermis to the underlying facial muscles, development of excessive skin, gravity, and ultraviolet radiation exposure. Fig. 242-3 illustrates a surgical defect on the upper lip of an elderly woman with prominent RSTL. RSTLs are most obvious on the face because unlike other muscles in the body that connect tendons and bones, facial muscles attach to the overlying skin. These lines can be induced by facial muscle movement in the young but inevitably become more pronounced with age. RSTLs usually run perpendicular to the underlying muscles. In most situations, the long axis of the excision should be placed parallel to the RSTL because they are often in the direction of the least tension for a scar. It is preferable to design flaps such that the majority of the scar lines fall within the RSTL.

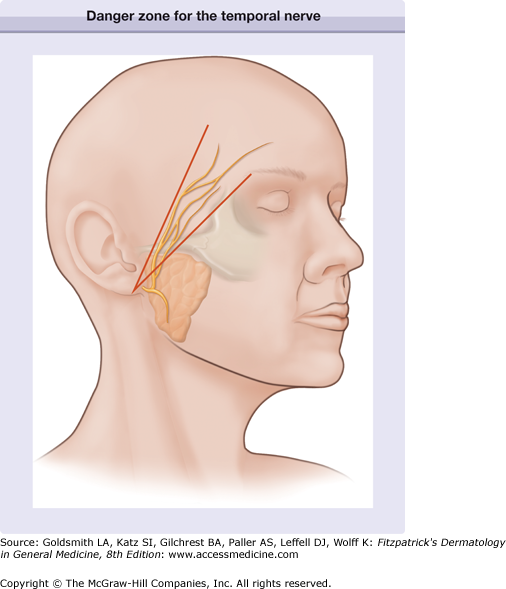

There are three main danger zones that are critical to understand while performing surgical procedures on the head and neck. Each of these zones involves a motor nerve and the muscles it innervates. It is important to confirm the proper function of these muscles before performing a procedure in these areas so that it can be readily determined whether an injury occurred during surgery.

The temporal branch of the facial nerve is at greatest risk for injury where it crosses the zygomatic arch. Injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve leads to an inability to elevate the eyebrows and brow ptosis and paralysis. Asymmetric appearance of the forehead can also occur because there will be a loss of the lines and wrinkles on the affected side. One easy method to delineate the danger area of the temporal nerve is to draw a line from the earlobe to the lateral edge of the eyebrow, and another line from the tragus to just above and behind the highest forehead crease (Fig. 242-4). In the area between these lines, over the zygomatic arch is where the nerve is superficial, and it is critical in this area to undermine just below the dermis in the superficial fat above the fascia.

Damage to the marginal mandibular nerve results in contralateral and upward pull on the mouth while the affected ipsilateral side of the mouth is fixed in a grimace with a lip droop. As it crosses the angle of the mandible at the inferoanterior border of the masseter, the marginal mandibular nerve is covered only by skin, subcutaneous fat, and fascia, which may be thin in this location, particularly in the elderly.

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve leads to the paralysis of the trapezius with winging of the scapula, shoulder drop, inability to shrug the shoulder, difficulty with abducting the arm and chronic shoulder pain. Transection of the spinal accessory nerve can occur when operating in the posterior triangle of the neck. This region is delineated by the clavicle inferiorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, and the trapezius muscle laterally and posteriorly. One can anticipate the location of the spinal accessory nerve by drawing a line connecting the angle of the mandible with the mastoid process. A vertical line is then drawn from the midpoint of this line 6 cm inferiorly. The point at which this line intersects the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is Erb’s point. The spinal accessory nerve emerges approximately from this point and lies superficially here, covered only by skin and fascia.

The term fascia refers to connective tissue that contains both fibrous and fat tissue in various amounts. Superficial fascia is the subcutaneous tissue that is immediately below the dermis. The deep fascia consists of more compact and highly organized collagen fibers. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) is the fascial system that envelops the muscles of the face. It stretches over the cheeks between the temporalis and frontalis muscles above and the platysma muscle below. The SMAS also attaches to the orbicularis oculi muscles anteriorly, the trapezius muscle posteriorly, and includes the fascia of the forehead and galea of the scalp. Most of the superficial muscles of the scalp and face insert into the skin either directly through fibrous bands running in the subcutaneous tissue or indirectly by attachment to the SMAS, which, in turn, is attached to the skin. In the lateral areas of the face, the SMAS is organized and more visible but becomes less discrete medially. Because of its attachment to the skin superficially and muscles deep, the SMAS coordinates a wide range of facial expressions. In addition, the SMAS is an important landmark because most major arteries and nerves run within or deep to it. Thus, dissection above the SMAS allows one to safely avoid injuring branches of the facial nerve.

The scalp is classically divided into five layers that are often referred to by the mnemonic SCALP. These layers from superficial to deep are: skin, subcutaneous tissue, aponeurosis (galea aponeurotica), loose connective tissue, and periosteum. Because the majority of the nerves and vessels of the scalp are superficial to the subgaleal space, this is an ideal undermining plane. However, it is also known as the danger zone because hematomas and infection can develop here and pass through the emissary veins into the meninges.

The forehead is best undermined immediately above the superficial fascia of the frontalis muscle. There may be little subcutaneous fat in this area. The temple should be undermined in the high fat/subdermal region to avoid damaging the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

The eyelids possess the thinnest skin of the body. The skin of the eyelids lies directly on the orbicularis muscle. Undermining should be performed above the muscle fascia to avoid causing significant bleeding and scars/contractures that can lead to ectropion.

The large, thick muscles of the lips and chin can make undermining challenging. The chin, in particular, has muscles broadly attached directly to the skin. Sharp undermining performed just above the superficial muscular fascia is appropriate. These areas are at high risk for bleeding, made even more precarious by functions such as talking and chewing.

The nose requires different levels of undermining in different regions. The dorsal nose can be easily undermined above the periosteum, especially when performing reconstruction with flaps. The distal, more sebaceous portion of the nose must be undermined in the subfibrofatty layer to allow the greatest tissue movement.

The cheeks can be safely mobilized in the high or mid subcutaneous fat. Care must be taken when undermining in the hair-bearing regions of the cheek in men, however. Here, undermining should be performed in the deep subcutis to avoid transecting hair follicles.

The neck can be safely undermined while staying above the superficial fascia. One must be careful in the posterior triangle of the neck. This region is delineated by the clavicle inferiorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, and the trapezius muscle laterally and posteriorly. The spinal accessory nerve lies superficially here, covered only by skin and fascia.

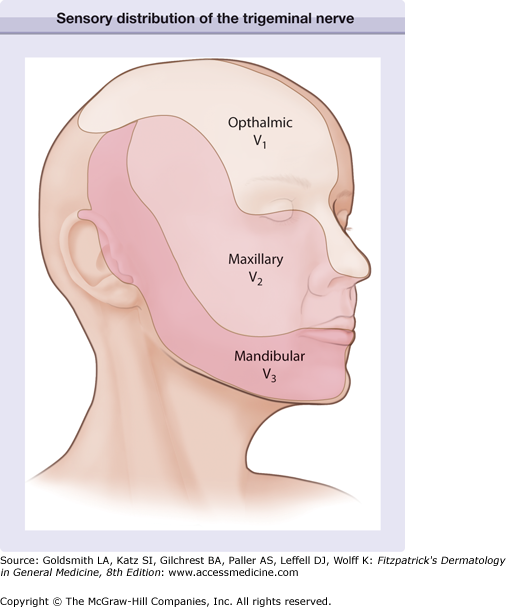

The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) provides the majority of the sensory innervation of the face (Fig. 242-5). It exits the skull via three foramina located bilaterally in the midpupillary line, the supraorbital, infraorbital, and mental foramina. The first branch, the ophthalmic nerve (V1), has several branches that supply the innervation to the superior portion of the face: the supraorbital, supratrochlear, infratrochlear, external nasal, and lacrimal nerves. The supraorbital (lateral) and supratrochlear (medial) nerves supply the forehead and anterior scalp and are branches of the frontal nerve (the largest branch of the ophthalmic nerve). They exit from two notches along the orbital rim: (1) supraorbital foramen or notch laterally, and (2) supratrochlear notch, medially. The infratrochlear branch (of the nasociliary nerve) supplies the glabella, nasal root, and bridge. The external nasal branch (or the dorsal nasal nerve) is a branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve of the nasociliary branch of V1. The external nasal branch supplies the dorsal nose and provides the anatomical explanation of Hutchinson sign that can occur in some cases of herpes zoster of the ophthalmic nerve. Vesicles on the nasal tip indicate that the eye may be involved because the nasociliary branch of V1 sends branches both to the nasal tip and the cornea. The lacrimal branch supplies sensation to the upper eyelid.

The second branch of the trigeminal nerve is the maxillary nerve (V2). The maxillary nerve supplies sensation to the lateral nose, lower eyelid, superior cheek, and anterior temple. The maxillary nerve gives off two main branches that supply the skin of the face. The zygomatic branch of the maxillary nerve gives rise to the zygomaticofacial nerve, which exits the skull through the lateral zygomatic bone and supplies a small area of the lateral canthus. In addition, the zygomatic branch also gives rise to the zygomaticotemporal nerve, which exits the skull through the anterior temporal fossa and supplies skin of the anterior temporal region. The largest branch of the maxillary nerve is the infraorbital nerve that exits the skull through the infraorbital foramen of the maxilla. This supplies sensation to the eyelid and superior cheek.

The third branch of the trigeminal nerve is the mandibular nerve (V3). Its branches provide sensory innervation to the lower lip, chin, mandibular and preauricular cheek, anterior ear, and the central temporal scalp. The mandibular nerve gives off three major cutaneous branches: (1) the auriculotemporal, (2) buccal, and (3) mental nerves. The auriculotemporal nerve innervates most of the temple, the temporoparietal scalp, the anterior ears, parts of the external ear canal, and the tympanic membrane. The buccal nerve lies deep to the parotid gland and supplies the skin over the buccinators, buccal mucosa, and the gingiva. The mental nerve exits through the mental foramen and is a continuation of the inferior alveolar nerve. The mental nerve supplies sensation to the lower lip and chin.

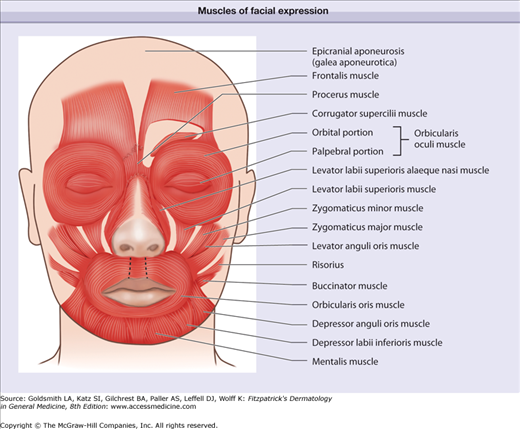

The scalp has two muscles overlying it, the frontalis anteriorly and the occipitalis posteriorly. These muscles are joined by a thick fascia centrally over the scalp, the galea aponeurotica. The frontalis muscle also covers the forehead and elevates the eyebrows. The eyebrows move medially and downward with contraction of the corrugator supercilii muscles. The procerus lies between the supercilii muscles and draws the skin of the forehead inferiorly to create the horizontal creases at the root of the nose. The orbicularis oculi muscle surrounds the eye and consists of an orbital and palpebral portion. The orbicularis oculi muscle serves to close the eyes with the palpebral part with both reflexive and voluntary control and the orbital part with voluntary control. The central sphincter-like muscle around the mouth is the orbicularis oris. This muscle helps purse the lips to form certain sounds and whistle. The lip depressors are depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris, and the mentalis. The lip elevators are the zygomaticus major, zygomatic minor, levator anguli oris, levator labii superioris, and the levator superioris alaeque nasi. The risorius helps retract the corner of the mouth. The buccinators and masseter muscles help with mastication (Fig. 242-6).

The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) provides innervation to all the muscles of facial expression. It exits the skull via the stylomastoid foramen, which lies deep in the infra-auricular sulcus and anterior to the mastoid process. The facial nerve enters the parotid gland at the level of the intertragic notch and usually divides into five branches within the substance of the gland. The well-known mnemonic “to Zanzibar by motor car” can be used to remember the five main branches: (1) temporal, (2) zygomatic, (3) buccal, (4) mandibular, and (5) cervical. For the most part, these nerves enter the muscles they innervate posteriorly and deep. A nice rule of thumb is that if one transects a nerve lateral to the midpupillary line, permanent paralysis can result and if the nerve is cut medial to this demarcation, most nerves will regenerate or have arborizations that will help provide additional innervation.

The temporal branch of the facial nerve exits the superior part of the parotid gland and crosses the zygomatic arch to innervate the frontalis, upper portion of the orbicularis oculi, and corrugator supercilii. Injury to the temporal branch leads to an inability to raise the eyebrows and brow ptosis. The zygomatic branch innervates the orbicularis oculi, nasal muscles, lip elevators, and the buccinators. Damage to the zygomatic nerve results in lower eyelid ptosis and an inability to close the eyes completely. The buccal branch also innervates the buccinators and lip elevators, as well as the orbicularis oris and risorius. Damage to the buccal branch leads to an inability to whistle. The marginal mandibular branch crosses the angle of the mandible at the inferior-anterior border of the masseter. It innervates the depressors of the mouth.

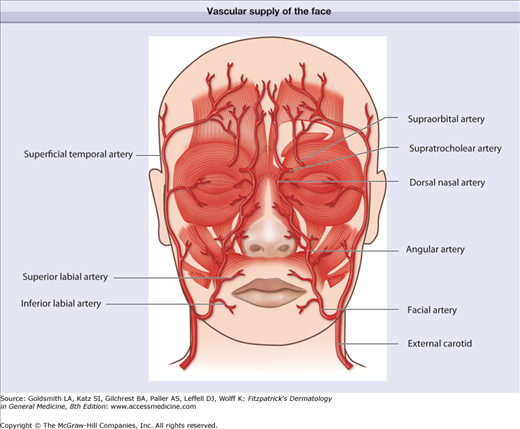

The blood supply of the face is almost entirely derived from branches of the external carotid artery (Fig. 242-7). Just posterior and medial to the angle of the mandible, the facial artery branches off the external carotid artery. The facial artery continues anteriorly and superiorly toward the angle of the mouth, giving off the inferior labial artery and superior labial arteries that supply the lips. The continuation of the facial artery in the nasofacial sulcus is called the angular artery. The angular artery continues superiorly to enter the orbit immediately over the medial canthal tendon where it anastomoses with the ophthalmic artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery. After giving off the facial artery, the external carotid artery then passes deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and enters the body of the parotid gland where it gives off the posterior auricular artery that supplies the postauricular scalp, the maxillary artery, and the superficial temporal artery. The terminal branch of the maxillary artery exits the infraorbital foramen with the infraorbital nerve as the infraorbital artery to supply the lower eyelids and infraorbital cheek.

The terminal branches of the internal carotid artery are the ophthalmic artery branches, the supraorbital artery, and the supratrochlear artery. The supraorbital artery emerges from the supraorbital foramen, whereas the supratrochlear artery emerges more medially. The internal and external carotid systems join in two places: (1) where the supratrochlear branch and the dorsal nasal artery anastomose with the angular artery and (2) where the forehead branches of the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries anastomose with branches of the superficial temporal artery.

The veins of the face parallel and lie posterior to the arteries. Unlike the veins of the trunk and extremities, facial veins have no valves. This allows blood to flow in either direction. Thus, in the central face where there are anastomoses between branches of the ophthalmic vein and of the angular vein, infection has easy access to travel along the ophthalmic vein to the cavernous sinus. The angular vein also communicates with the deep facial vein and pterygoid plexus.

The lymphatic vessels of the face generally drain from superficial to deep and medial to lateral and caudad. While the general drainage patterns are described here, variations can occur. The posterior scalp drains to the postauricular and occipital nodes. The lateral and superior face, the forehead, and the lateral eyelids drain to the parotid nodes. The medial and inferior face, including the medial eyelids and lateral lips, drain to the submandibular nodes. The middle two-thirds of the lower lip and the chin drain to the submental nodes. These nodes can be optimally palpated by performing a bimanual exam with a gloved hand feeling through the floor of the mouth.

The lymph nodes of the head and neck eventually drain into a terminal series of nodes (deep cervical nodes) and finally into the lateral internal jugular chain.

Preoperative Assessment

Preoperative assessment is critical for a successful procedure. It allows one to anticipate and possibly correct factors that predispose to adverse outcomes and minimize complications. A fairly thorough medical, drug, and medication allergy history provides an accurate picture of the patient’s health status. Questioning the possibility of pregnancy in women of childbearing age should not be overlooked, as local anesthetics and antibiotics may be contraindicated. Patients with inherited bleeding disorders can also be identified and, when possible, given clotting factors to correct for these disorders. Uncontrolled hypertension may predispose to increased intraoperative and postoperative bleeding. In addition, poorly controlled diabetes and immunosuppression with use of systemic steroids for medical conditions, such as autoimmune disorders or organ transplantation, may affect healing time. Information from the social history can also have a bearing on the surgery. For instance, healing can be adversely affected if the patient smokes, and this may impact the decision to perform a flap or graft. Alcohol consumption can increase the risk of bleeding because of its qualitative effect on platelets. Finally, knowledge of the patient’s resources and support at home is helpful when providing instructions for postoperative care.