IN THIS CHAPTER

- •

Introduction 5

- •

Topography 5

- •

Vascular Anatomy 9

- •

Lymphatics 9

- •

Nerves 9

When performing abdominal contouring procedures, it is necessary to understand the anatomy of the abdominal region and how it relates to the specific surgical operation being performed. The vascularity of the abdominal soft tissue is particularly important, considering the large area that is often undermined during abdominoplasty, the common use of concurrent liposuction, and the fact that the tissue is often closed under tension. Understanding the muscular and fascial components of the abdominal wall is important for myofascial plication and hernia repair. The sensory distribution is also important when considering incision placement for abdominal body contouring procedures. Specific caveats of the abdominal anatomy are important to note, as they play an important role in simplifying and safely achieving excellent aesthetic results in abdominal contouring procedures.

Introduction

The anatomy of the abdominal wall and overlying soft tissues is both straightforward and elegant. This chapter will review the relevant anatomy of abdominal contouring procedures, including topography, superficial structures, deep structures, vascular supply, the lymphatic system, and the innervation of the abdominal soft tissue. Important aspects of each of these categories as they pertain to abdominal contouring procedures will be discussed.

Introduction

The anatomy of the abdominal wall and overlying soft tissues is both straightforward and elegant. This chapter will review the relevant anatomy of abdominal contouring procedures, including topography, superficial structures, deep structures, vascular supply, the lymphatic system, and the innervation of the abdominal soft tissue. Important aspects of each of these categories as they pertain to abdominal contouring procedures will be discussed.

Topography ( Box 2.1 )

Patients who present for abdominoplasty or abdominal contouring procedures do so with a variety of different body types and levels of fitness. Some may have excess skin laxity and little excess adiposity; others may have extensive excess adiposity; and yet others may have neither or both, along with various degrees of abdominal myofascial laxity. The topography of the abdominal area will differ among these different patients, but it is always important to identify and visualize the pertinent anatomy in order to properly plan and execute the desired abdominal contouring procedure.

- •

The aesthetic result is determined largely by the preoperativemarking/surgical plan.

- •

Preoperative marking begins by identifying key landmarks, including the xiphoid, anterosuperior iliac spines, and the pubic symphysis.

- •

The soft-tissue structures, including linea alba, paired linea semilunares, and the tendinous insertions of the rectus abdominus, are particularly important when lipo-etching is planned.

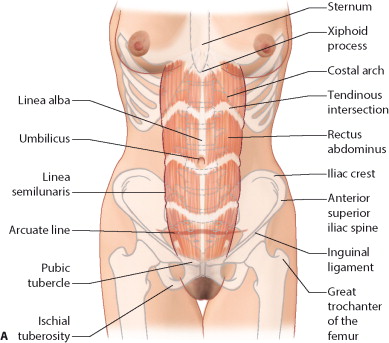

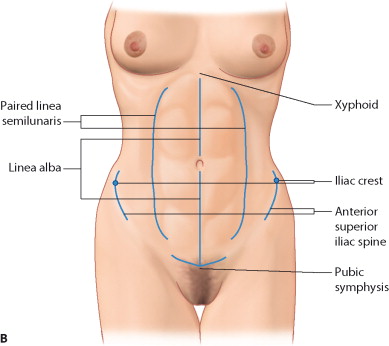

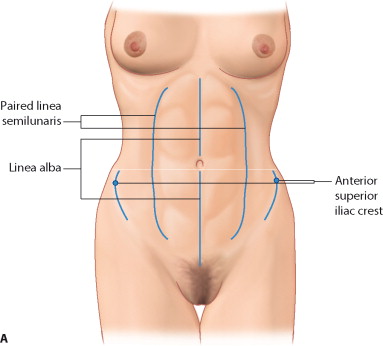

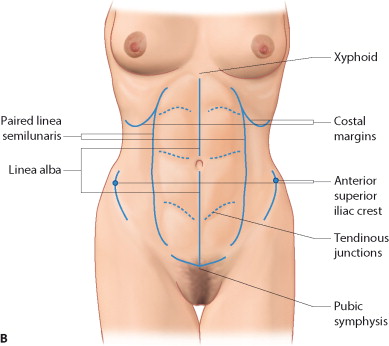

There are a number of important bony and soft-tissue landmarks that should be identified during preoperative marking ( Fig. 2.1 ). The bony landmarks include the paired anterior–superior iliac crests, the pubic symphysis, the xiphoid, and the costal margins bilaterally. These landmarks can usually be palpated in all patients regardless of body mass index (BMI) or habitus, although it may be somewhat more difficult in patients who are significantly overweight. These bony landmarks will serve as the initial reference points for the preoperative markings to identify the midline and to ensure the symmetry of the final planned incision. It is important to note that the marks on the skin may shift considerably relative to the bony landmarks, especially in patients with significant soft-tissue laxity. This is why it is important for the preoperative marking to be performed with the patient standing.

The soft-tissue landmarks include the linea alba, the paired linea semilunaris, and the transverse tendinous junctions of each rectus abdominis muscle ( Fig. 2.2 ). It is interesting to note how much of the aesthetic appeal of a healthy, fit abdomen is attributed to these landmarks that are primarily associated with the anatomical architecture of the rectus abdominis muscles. These landmarks are particularly important in fairly thin or fit patients who desire improved abdominal definition. Abdominal liposuction for improved definition, especially when it involves lipo-etching, relies on knowledge and identification of these landmarks.

Superficial Structures

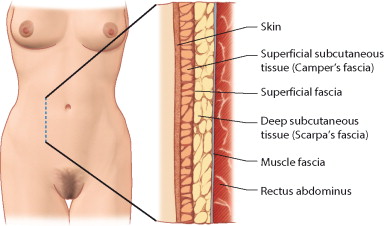

For the purpose of discussing anatomy in the context of abdominal body contouring procedures, the abdominal layers can be separated into superficial and deep structures. The superficial structures include skin, the superficial subcutaneous fat associated with Camper’s fascia, Scarpa’s fascia or the superficial fascial system of the abdomen (SFS), and the deep subcutaneous fat or sub-Scarpa’s fat (sub-Scarpal fat) ( Fig. 2.3 ). The proportion of the superficial to the deep fat layer is variable among patients, depending on their BMI and body habitus. The sub-Scarpal fat is usually less compact, with less fibrous architecture than the fat superficial to Scarpa’s fascia. Scarpa’s fascia, or the superficial fascia system of the abdomen (SFS), is an important anatomic layer in body contouring in general, and in abdominoplasty procedures in particular. Scarpa’s fascia is the structure that allows surgical closure in abdominoplasty procedures to be performed under remarkably high tension without vascular compromise to the skin. As most of the tension of the closure is placed on the SFS, and the skin closure is subjected to considerably less tension, a good-quality scar can be achieved.

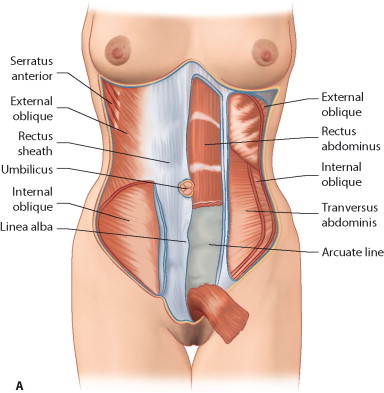

Deep Structures

The deep structures include the deep muscular fascia overlying the abdominal wall musculature and the abdominal wall muscles themselves, with all of the corresponding layers of investing fascia ( Fig. 2.4 A–C ). The anatomy of the rectus sheath is of considerable importance because the majority of myofascial plication methods involve approximating this tissue. The three components of the lateral abdominal wall – the external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis – come together medially as fascial extensions to form the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. Superior to the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the fascial extensions of the external oblique and half of the internal oblique. The fascial extension of the internal oblique muscle splits around the rectus abdominis above the arcuate line and reforms at the linea alba. Inferior to the arcuate line the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the fascial extensions of all three muscular layers, with the tissue posterior to the rectus abdominis consisting of only the peritoneum ( Fig. 2.4 E and F ). One can also include the intra-abdominal fat as one of the deep abdominal structures, as for some patients the presence of extensive amounts of such fat can play a role in the final aesthetic result, limiting how much flattening of the abdomen can be accomplished.