Fig. 22.1

Constriction bands involving the upper and lower extremities. The hand deformity shows constriction bands, lymphedema, acrosyndactyly, and digital amputations

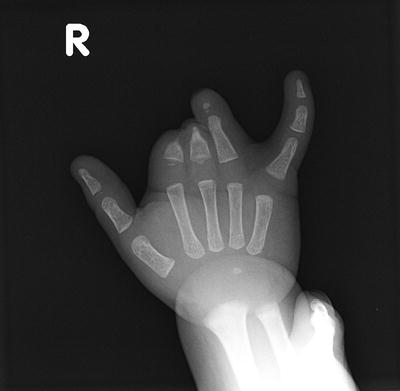

Fig. 22.2

An X-ray demonstrating transverse arrest of development and tapering of distal skeletal bones due to constriction bands

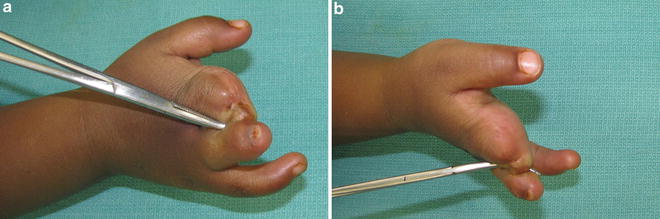

Digital malformation is a classic clinical finding in ABS that is secondary to amputations and phalangeal hypoplasia. Acrosyndactyly is often associated with digital amputations. In acrosyndactyly there is a normal separation of the digits, however the digits are fused together distally. Proximal to the point of fusion, interdigital sinuses or tracts can be found and probed in between the digits (Fig. 22.3) that indicate normal separation of the fingers and remnants of webspaces, hence the synonyms pseudo-syndactyly or fenestrated syndactyly have been used to describe this condition. Contrary to true syndactyly, acrosyndactyly is almost always not associated with any underlying bony fusion. The frequency of digital involvement with ABS has been reported by Kino [14], Flatt [30], and Foulkes and Reinker [29]. In those three reports central digits were the most affected whilst the thumb is the least affected digit with ABS. In the central digits the ring finger is most commonly involved followed by long then index and finally the small finger. Several reasons may explain why longer digits are more affected than the thumb. Kino stated that longer digits are more liable to external compression forces in the uterus, whereas in a clinched fist the other digits usually protect the thumb. A second reason could be the different embryonic stage of development of different digits. The development of the thumb precedes central digits and assuming that constriction bands occur after the period of major organogenesis as suggested by Foulker and Reinker, may explain the decreased tendency of thumb involvement in ABS. Finally, the time difference of fetal development of upper and lower limbs may also explain the different incidence of constriction band involvement of the hands and feet.

Fig. 22.3

Acrosyndactyly with a probe in the sinus tract

Classification

Several classifications have been devised for ABS based on the severity and location of the constriction bands [9, 31, 32]. Hall (1982) classified constriction rings into mild, moderate, and severe based on whether constriction rings are deep enough to cause lymphedema or amputations. He considered stage 1 as mild constrictions that do not result in lymphedema, stage 2 moderate constrictions resulting in lymphedema, and stage 3 as severe constrictions causing amputations. Weinzweig (1995) further subdivided Hall’s classification by adding two intermediate stages that include a moderate constriction ring with distal deformity, syndactyly, or discontinuous neurovascular or musculotendinous structures without vascular compromise with or without lymphedema and severe constriction with progressive lymphaticovenous or arterial compromise with or without soft-tissue loss, and finally he added a fourth stage that include intrauterine amputation. Despite this, the most widely accepted and clinically relevant classification is the Patterson classification (1961), which has four categories:

1.

Simple constriction rings

2.

Constriction rings associated with deformity of the distal part with or without lymphedema

3.

Constriction rings associated with acrosyndactyly

4.

Intrauterine amputations

Additionally, cases that fall in the third category (constriction rings with acrosyndactyly) are further subdivided into three types:

Type I: Conjoined fingertips with well-formed webs of the proper depth.

Type II: The tips of the digits are joined, but web formation is not complete.

Type III: Joined tips, sinus tracts between digits, and absent webs.

Treatment

The highly variable clinical picture among patients with ABS requires the treatment to be tailored to meet individual patient’s requirements. A careful preoperative evaluation of underlying medical and surgical conditions must be considered to minimize the risk of anesthesia. The surgical treatment of ABS may range from an elective repair to an emergent limb-sparing or amputation procedures.

Superficial non-constrictive rings without distal swelling or neurovascular compromise may require no treatment or may be repaired electively to improve aesthetic appearance. For deep circumferential rings, the standard treatment includes Z-plasty and W-plasty in the presence of good distal function. In patients with acrosyndactyly, resurfacing of the webspace is required to separate digits and improve finger function. In cases of a constrictive band resulting in overt ischemia or osteomyelitis, distal amputation may be required [3, 23, 24]. Additionally, reconstructive procedures such as finger-to-toe transfers, bone-lengthening procedures, and pollicization procedures have been performed to restore function in cases of digital hypoplasia and amputation. Finally, fetoscopic band release for limb preservation in severe constriction rings has been used successfully [33, 34]. However, the rate of spontaneous abortion with these procedures has been reported between 6 and 10 %, a risk that should be carefully discussed beforehand with the parents together with all the pros and cons associated with this type of treatment.

Preoperative Considerations

Certain factors should be considered prior to surgery that include the appropriate timing for surgery, the amount of tissue to be excised or released, and the possibility for additional surgery of underlying structures such as tendons or nerves. The timing of surgery is mostly driven by the severity of the disease. Surgery should be considered in the first few days of life for constriction bands associated with severe distal edema and ischemia. In less severe cases, surgery should be performed electively, not “too early” to minimize the risk of anesthesia and not “too late” when hand function can be affected. In patients with acrosyndactyly, finger separation is usually recommended between 6 and 12 months to allow for longitudinal skeletal growth of the digits. Adhering to principles of congenital hand anomalies, the aim should be to complete all surgery before the child enters school, if possible. In the operating room, a two-team approach is recommended especially in cases of multiple limb involvement so that several procedures can be performed at the same setting, thus minimizing the total number of surgeries required.

The second preoperative consideration is the amount of tissue that needs to be released or excised. Most surgeons advocate the release of only 50 % of the constriction bands especially if the constrictions are located around the digits to preserve the vascular integrity. A second stage procedure can be scheduled 6–12 weeks following the first procedure to complete the repair. The third consideration is involvement of underlying structures. Underlying tendons and nerves can be affected by deep constriction bands and may require repair or reconstruction at the time of constriction band repair. The risk of additional procedures should therefore be discussed with the parents/family prior to surgery [3, 27].

Constriction Band Release

The standard treatment for constriction bands is excision of the constriction ring and the subcutaneous fibrous tissue followed by soft-tissue rearrangement by a Z-plasty or a W-plasty. A standard 60° Z-plasty with transposition of large skin flaps is recommended to preserve the viability of the skin flaps. The advantage of using a Z-plasty is twofold; first it breaks the tension line across the scar and second it adds length to the area of circumferential constriction (Fig. 22.4), whereas W-plasty only breaks the tension across the scar without incorporating further length. The two techniques alone do not address the resultant contour defect that arises after the excision of constriction rings and underlying subcutaneous tissue, an outcome that is considered not aesthetically pleasing. To prevent contour deformity, Upton [35] described a technique that involves excision of the constriction ring and underlying scarred tissue, then a portion of the adjacent healthy adipose tissue on both sides of the defect is separated from the dermis of overlying skin and mobilized to the center of the defect to fill the void. Subcutaneous veins should be preserved to facilitate venous drainage and prevent post-operative congestion. The skin flaps of the Z-plasty are then transposed separately over the adipose tissue. The skin suture line should be closed a few millimeters away from the underlying adipose suture line (Figs. 22.5 and 22.6). Repair of constriction rings around the fingers follows the same principles; however, skin incisions constituting the Z-plasty should be designed in a way that the final scar is placed along the midlateral lines to minimize skin contractures and visible scarring. At times the constriction ring is broad enough that an excision and closure by a Z-plasty is not possible. In these circumstances a local skin flap such as a cross finger flap can be executed to cover the resultant skin defect [27].

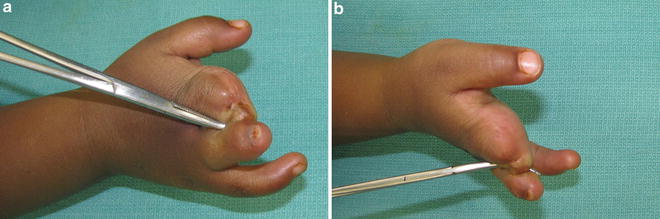

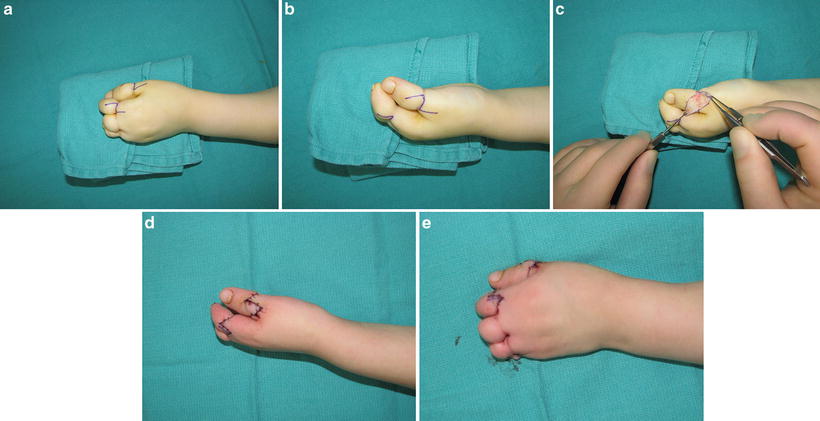

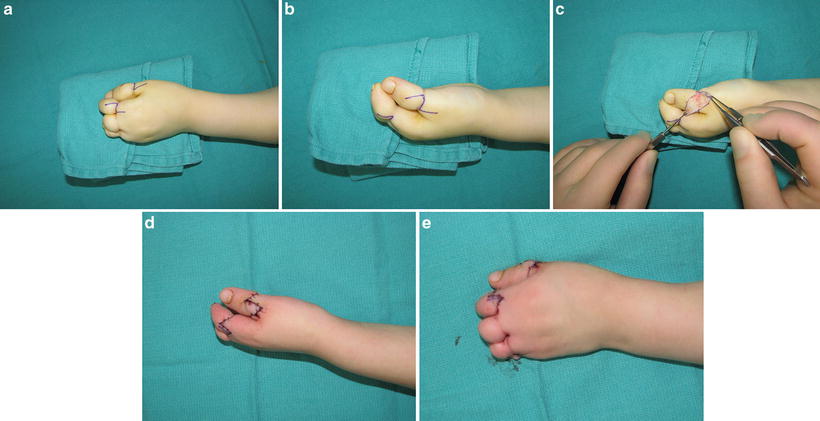

Fig. 22.4

Correction of constriction rings around digits using a Z-plasty

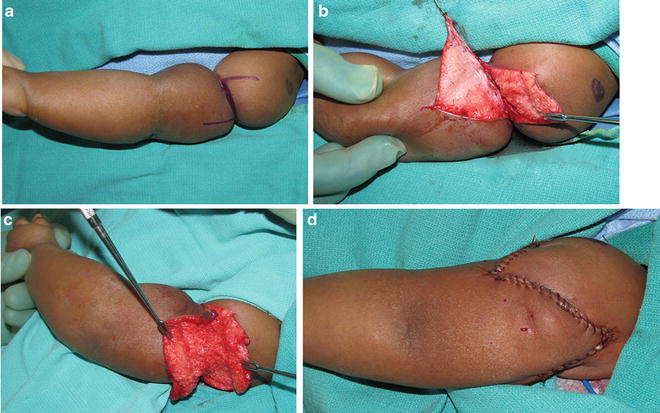

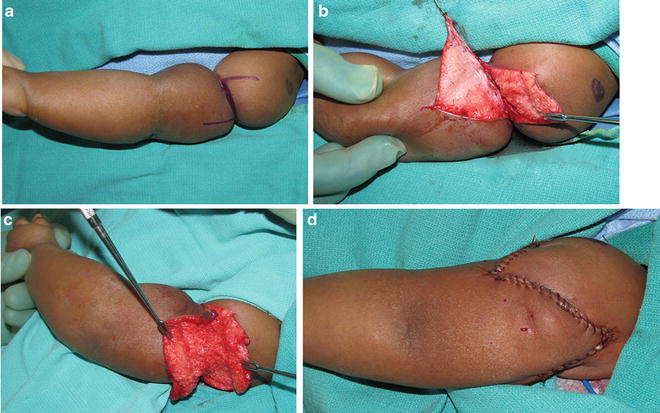

Fig. 22.5

Correction of a circumferential constriction band around the arm using a Z-plasty

Fig. 22.6

Schematic drawings for releasing of the constriction band with Upton’s technique. (a) Excision of all skin in the side walls. (b) Debulking of excess adipose tissue. (c) Subcutaneous adipose flaps are mobilized as needed to correct the contour deformity. (d) Skin and subcutaneous closures are preferably staggered

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree