Fig. 15.1

(a) Widespread, diffuse hair loss in a renal transplant patient taking tacrolimus. (b) Excellent response to minoxidil

Other reports indicate many patients recover from alopecia when tacrolimus doses are minimized. Finally, some cases require complete discontinuation of tacrolimus. When cyclosporine is used as a tacrolimus replacement, patients are able to take advantage of its hypertrichosis side effect.

Infectious

Hepatitis B

Although alopecia is not associated with viral hepatitis B (HBV) per se, it has been reported following HBV vaccination. Wise and colleagues reviewed spontaneous reports submitted to FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System [39]. They identified 46 cases of alopecia attributed to the HBV vaccine. Twenty-five percent of these patients demonstrated repeated hair loss upon rechallenge. The authors propose some type of immunologic target overlap between the vaccine and the hair follicle but the exact pathogenesis is unclear.

The details of each case varied widely from elapsed time between vaccination and hair loss, pattern of hair loss and extent of recovery although most patients had a full recovery. Other authors have reported similar incidences of alopecia following HBV vaccination [40].

Hepatitis C

It is estimated that about 40 % of patients with hepatitis C (HCV) exhibit extra-hepatic manifestations. In the realm of dermatology, the most common associations are mixed cryoglobulinemia presenting as vasculitis, porphyria cutanea tarda, and lichen planus [41]. Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disease in which patients acutely develop sharply demarcated round patches of non-scarring alopecia than can become confluent. Hair anywhere on the body can be affected. There are scant reports of alopecia areata specifically attributed to HCV virus infection. Paoletti and colleagues studies a cohort of 96 patients with HCV and found that two had alopecia areata [42]. Conversely, Jadali found that of 45 patients with alopecia areata, none had anti-HCV antibodies in their serum [43]. Figure 15.2 demonstrates a patient with HCV, alopecia areata and vitiligo.

Fig. 15.2

Erosions and scaring alopecia in a patient with hepatitis C infection

Callen and colleagues reported one case of scarring alopecia attributed HCV infection. The patient developed porphyria cutanea tarda with sclerodermoid features involving the scalp (Fig. 15.2) [44].

Given the association between lichen planus and HCV, one might expect an increased incidence of lichen planopilaris in patients with HCV. This, however, is not the case. Perhaps it is underreported given the well-established association between lichen planus and HCV infection.

More often, alopecia is associated with treatments for hepatitis. There are many cases of alopecia universalis (loss of all scalp and body hair) in association with pegylated interferon and ribivarin treatment [45, 46]. Enhanced cytotoxic T cell activity is among the mechanisms of action for pegylated interferon. This, in addition to causing an immune shift from Th2 to Th1 response, is identified as the mechanism of this form of alopecia.

In reported cases of alopecia universalis attributed to pegylated interferon and ribivarin, patchy hair loss began after 4–6 months of treatment. Within 3 months, loss of scalp and body hair was complete. Spontaneous hair regrowth began 3–9 months after the treatment was completed.

Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Alopecia is a frequent finding in patients with HIV infection. There are many potential contributing factors including the HIV infection itself, secondary infections, immune and endocrine dysfunction, and medications. Nutritional deficiencies may also contribute. Alopecia may occur in the form of telogen effluvium with dystrophy of the hair shafts, texture changes of the hair, and alopecia areata.

In 1996, Smith and colleagues published their clinical and histologic findings of ten patients with HIV and alopecia [47]. All ten patients were diagnosed with telogen effluvium with telogen hair counts ranging from 24 to 50 %. In all cases, there was some degree of dystrophy of the hair shafts. They used scanning electron microscopy to demonstrate a range of findings from small, local defects to marked dystrophy and transverse fractures (Fig. 15.3). All of the patients reported straightening of their hair which was attributed to the changes in the hair shaft.

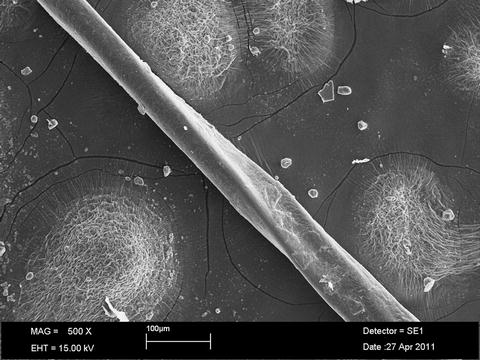

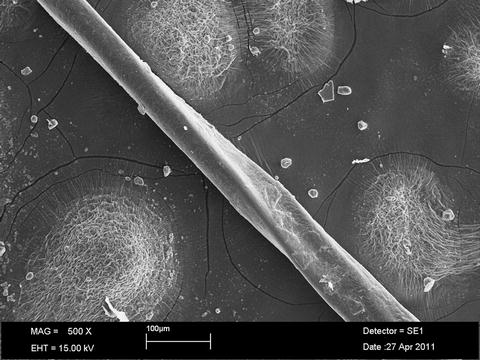

Fig. 15.3

Dystrophic hair showing twisting and a longitudinal ridge in a patient with HIV and alopecia. Scanning electron micrograph. Original magnification 500×

Mirmirani et al. evaluated hair changes in 196 HIV infected women and 50 non-infected women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) [48]. Twenty-eight percent of women with HIV reported finer hair compared with only 12 % of the non-infected group. This was significantly associated with higher viral loads. Interestingly, long eyelash was the only other statistically significant finding as it was also associated with higher viral loads. Other changes in hair texture (straighter, curlier, coarser) were reported but did not reach statistical significance.

Straighter, finer hair is a frequent finding in HIV disease, but the same changes have been reported outside of HIV disease and should not be considered pathognomonic [49].

Alopecia areata and alopecia universalis have been reported in association with HIV. An early case of alopecia universalis attributed to HIV infection was reported by Ostlere et al. Two years after the patient tested positive for HIV infection, he developed a typical course of patchy hair loss which rapidly degenerated into loss of all scalp and body hair [50]. Several similar cases have been reported since. There are a few theories regarding the mechanism by which HIV infection induces alopecia areata. Most emphasize a change in the immune cell balance (T helper versus T suppressor cells or CD4/CD8 ratios). In one case, a patient developed trichomegaly (seen in advanced immunosuppression) in addition to alopecia areata which requires immune activation. This case highlights the selective pathogenesis of HIV infection [51].

In patients with HIV infection, alopecia can occur in a number of different forms. There are no set criteria for HIV induced alopecia; therefore, in association with appropriate risk factors, clinicians should always consider HIV as a cause of alopecia.

Autoimmune

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Alopecia in the setting of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can take on many forms. It is easiest to consider it in terms of non-scarring versus scarring types. In non-scarring alopecia, hair follicles are retained and the potential for hair regrowth remains. The opposite is true of scarring alopecia in which hair follicles are replaced with scars.

Telogen effluvium is a form of non-scarring alopecia in which patients experience diffuse hair shedding in response to any number of psychological or physiological stressors. It is a frequent occurrence with flares of SLE [52]. Telogen effluvium resolves once lupus is controlled although patients may lose 30 % or more of their hair. Complete regrowth can be expected, assuming the underlying cause is corrected, within 6–12 months. Telogen effluvium overlaps significantly with the phenomenon termed “lupus hair.” Lupus hair refers to short, brittle hairs along the frontal hair line that also seem to occur during flares of disease. It is associated with recession of the frontal hair line. Hairs in this region are either broken or replaced with vellus hairs. This hair also regrows in a normal fashion once the SLE is under control.

Yun et al documented hair loss events in 122 patients with SLE before and after their SLE diagnosis [53]. In total, 104 patients experienced some form of hair loss. Eighty-six patients experienced hair loss after the SLE diagnosis was made, the majority (65 %) of which was characterized by diffuse, non-scarring loss consistent with telogen effluvium. Fifteen percent of the patients experienced non-scarring patchy alopecia consistent with alopecia areata. Interestingly, 26 % of the patients interviewed experienced more than two patterns of alopecia after the SLE diagnosis was made.

Alopecia areata is a non-scarring form of hair loss that generally presents with acute onset, well demarcated, round patches of alopecia which can become confluent. Werth and colleagues evaluated 39 patients with SLE and found that alopecia areata developed in 10 % (4/39) [54]. Histopathology demonstrated a granular deposition of IgG which is only rarely seen in alopecia areata. Patients responded to standard alopecia areata treatment (i.e., intralesional corticosteroids). A larger study has not been published.

Seven percent of patients in the Yun study experienced discoid lupus, a form of scarring alopecia. Other sources suggest a similar incidence ranging from 4 to 14 % of patients with SLE having discoid lupus on the scalp [55]. Conversely, discoid lupus without SLE is not uncommon, although the exact incidence is difficult to pinpoint. There appears to be some overlap between the immunologic mediators of lupus and lupus nephritis. IL-17, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, has been demonstrated to have an important role in both entities [56].

Discoid lupus on the scalp most commonly affects young adult women with onset between ages 20 and 30 years. Classic lesions show an erythematous plaque that evolves into a centrally depressed, depigmented, alopecic plaque. There is associated follicular plugging. The mnemonic PASTE has been suggested to describe discoid lupus lesions: plugging, atrophy, scale, telangiectasia, erythema [52]. An erythematous or hyperpigmented active edge is retained. Conchal bowl of the ear involvement is also common, occurring in about 50 % of patients with scalp involvement. Symptoms range from none to pruritus and pain.

Biopsy can help distinguish discoid lupus from other forms of scarring alopecia such as central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and lichen planopilaris. The histology of discoid lupus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, dermal fibrosis, and follicular plugging as might be expected given the clinical appearance. Other key features are basement membrane thickening, basal vacuolization, and mucin deposition in the papillary dermis.

Alopecia in the setting of SLE may present in many different ways. The most frequent presentation is that of telogen effluvium which is incited by a lupus flare and is self-resolving once the flare is controlled. Alopecia areata in SLE responds to treatment in the same way that non-lupus related alopecia areata responds. Discoid lupus results in permanent scarring which cannot be reversed. Early intervention may limit its progression.

Infiltrative

Amyloidosis

Given that any organ system can be affected by systemic amyloidosis, one might expect alopecia to be a common finding. On the contrary, it is not. There are only a few published case reports describing alopecia in the constellation of signs and symptoms of systemic amyloidosis.

The first case of systemic amyloidosis causing alopecia was reported in 1991 by Hunt and colleagues [57]. The patient presented with diffuse, non-scarring alopecia involving the scalp and body. Hair pull test on the scalp was positive. The patient also demonstrated pinch purpura and easy bruising, cutaneous features commonly associated with systemic amyloidosis. Two scalp biopsies (taken 7 months apart) both demonstrated perifollicular deposition of amyloid.

Lutz and Pittelkow describe a patient who presented with gradual, progressive alopecia beginning 6 years before any other signs or symptoms of amyloidosis were identified. The alopecia involved scalp and body hair. An initial scalp biopsy was read as nonspecific and the patient failed a trial of 2 % minoxidil. With time, the patient also developed brittle fingernails and erythema and thickening of the palms. A subsequent biopsy from the scalp with special staining (Thioflavine-T and Congo red) confirmed the diagnosis [58]. Figure 15.4 shows a patient with a similar pattern of alopecia.

Fig. 15.4

Diffuse alopecia of the scalp in a patient with amyloidosis

Barja and colleagues reported a case in which the patient presented with a 1 year history of dyspnea, dysphagia, and weakness [59]. On exam, the patient had diffusely decreased density of scalp hair and fingernail dystrophy which had been present for years. Scalp biopsy was diagnostic in this case, demonstrating amyloid deposition.

As with the patients reported, alopecia in the setting of systemic amyloidosis presents with diffuse, non-scarring alopecia. Often scalp and body hair is affected. Hair pull test is usually positive. Histopathology demonstrates perifollicular amyloid deposition. Minoxidil is not effective. Instead, therapy should be directly targeted to the disease process underlying the amyloidosis.