6

Advanced Occipitocervical Surgery in Children

In general, anomalies of the craniovertebral junction (CVJ) can be divided into three main categories: congenital, developmental, and acquired. For purposes of simplicity and clarity, developmental and acquired anomalies are often placed under the same heading.

Congenital CVJ anomalies are those that are present at birth and remain relatively static over time. Their presence ultimately may lead to clinical instability and require treatment. Common examples of such anomalies include occipitalization of the atlas, basilar invagination, and segmentation failure of C1–C2 or C2–C3. Developmental anomalies are those that arise out of an ongoing pathological process that directly affects the CVJ, such as Down syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Acquired anomalies arise as part of a systemic disease, infection, inflammation, or trauma. Examples include traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteomyelitis.

A surgical physiological approach to CVJ problems has been proposed by Menezes.1 He argues that several factors must be taken into account for a complete understanding of a given anomaly: (1) the reducibility of the lesion; (2) the direction and manner of the encroachment of the lesion, along with neurological deficits; (3) lesion etiology (e.g., bony versus soft tissue, intracranial versus extracranial, intramedullary versus extramedullary); and (4) the growth potential of the affected area. Stability of the CVJ is paramount. Reducible lesions require reduction prior to operative stabilization, whereas an irreducible lesion may be fused in situ. Postoperative stabilization may be necessary for mass lesions requiring enough bone or ligament removal to cause instability. This chapter reviews the clinical presentation of children with CVJ abnormalities, discusses the surgical and nonsurgical management of these disorders, and presents a detailed discussion of newer techniques of craniocervical instrumentation.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The clinical findings that result from disorders of the CVJ are diverse and reflect the densely packed ascending and descending fiber tracts, brain stem nuclei, and cranial nerves that reside within this region. Each CVJ abnormality varies in its degree of bony or soft tissue deformity, its clinical effects on neurovascular structures, and its associated effects on adjacent skeletal anatomy. Therefore, individual patients present with their own constellation of clinical findings. These findings may result from compression or compromise of the lower brain stem, cervical spinal cord, cranial nerves, or vascular structures and may have secondary effects such as progressive herniation, syringohydromyelia formation, or hydrocephalus.

The most common presenting symptom is pain, which may be manifested by headache or neck discomfort. Suboccipital headache may be caused by irritation of the second cervical nerve as it passes through the atlantoaxial joint capsule. Localized neck pain is most commonly attributed to destruction or disruption of periosteal or soft tissue structures brought about by the disease process. Other symptoms are most often a part of specific neurological or vascular syndromes.

Symptoms may progress insidiously and may present with false localizing signs.2 In some rare instances, the patient may present with catastrophic neurological deterioration or even sudden death. A history of a minor antecedent trauma resulting in rather rapid neurological decline is not uncommon.2

General physical examination of the patient is often normal but may reflect findings associated with a congenital abnormality such as Klippel-Feil syndrome (web neck, low-lying hairline, and limitation of neck motion) or a systemic disorder such as cancer. Torticollis, scoliosis, and facial asymmetry are common findings associated with congenital anomalies. A small, dysmorphic stature is found in patients with skeletal dysplasias, including achondroplasia, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, and other metabolic forms of dwarfism. Systemic disorders associated with CVJ abnormalities have a myriad of possible associated physical findings too numerous to include here. Careful attention to detail may help a practitioner reveal findings that unlock an associated diagnosis.

Neurological findings include myelopathy and cranial nerve palsies. Myelopathy presents as varying degrees of weakness or sensory disturbance in the upper or lower extremities. The myelopathy may mimic a “central cord syndrome” because of the preferential distribution of fibers subserving fine upper extremity motor movement within the corticospinal tract.3 Motor myelopathy is attributed to repetitive trauma of the pyramidal tracts and chronic compression of the spinal cord at the cervicomedullary junction.4 Bladder disturbance tends to parallel the motor myelopathy. Sensory myelopathy is most often manifested by symptoms associated with posterior column dysfunction. Cranial nerve and brain stem dysfunction produces a wide variety of findings. Sleep apnea, dysphagia, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, downbeat nystagmus, hearing loss,3 and palatal/pharyngeal dysfunction are all common clinical manifestations of CVJ abnormalities. Abnormal cranial nerve signs may be attributed to trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerve impingement.

Vascular insufficiency may produce symptoms or signs associated with basilar migraines, syncope, vertigo, intermittent hemiparesis, altered consciousness, or transient visual field loss. These findings may be associated with compression or occlusion of the vertebral artery, anterior spinal artery, or perforating arteries of the spinal cord. The vascular-related symptoms or signs may be provoked by craniocervical rotation or angulation, often as a result of occult occipitoatlantal or atlantoaxial instability.

Management of Craniovertebral Junction Lesions

Management of Craniovertebral Junction Lesions

Conservative Management

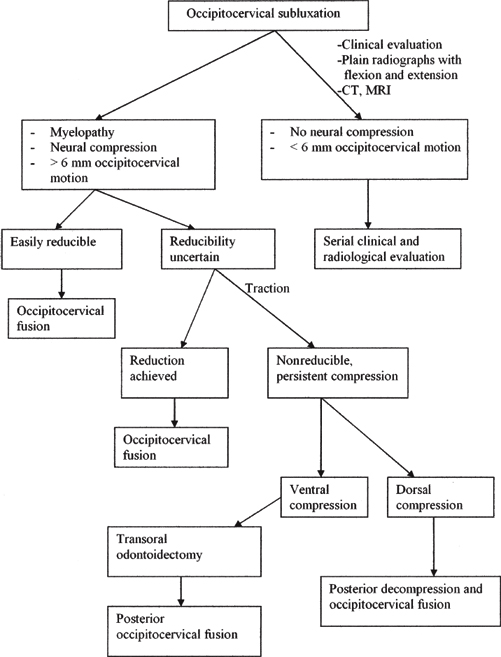

Figure 6–1 Algorithm for treatment of occipitocervical instability.

Only a minority of patients with CVJ abnormalities require surgery. Judicious patient selection and careful application of conservative measures may save a patient from inappropriate surgery and its attendant risks.5 Algorithms that deal with CVJ problems may assist in the patient selection process (Fig. 6–1). Issues to be considered are the stability of the CVJ, the reducibility of the lesion, the presence or absence of neurovascular compression, the natural history of the disease, and the growth potential of the patient. Some patients with a stable CVJ and minimal or no neurological symptoms and potentially troublesome pathology (e.g., occipitalization of the atlas) may be managed safely with a soft cervical collar and seen in follow-up periodically. Others with a stable CVJ and a known benign natural history (e.g., an adolescent with Down syndrome6) may be reexamined only if symptoms occur. Obviously, clinical judgment must be exercised in each case.

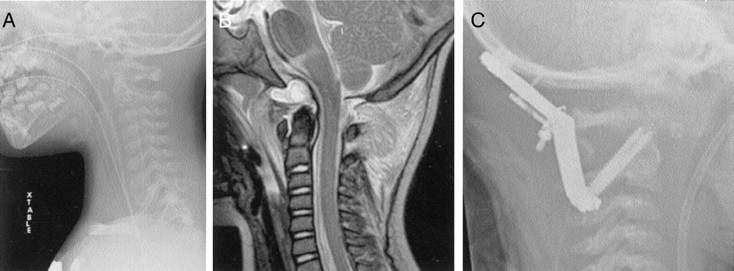

Figure 6–2 A 22-month-old boy with atlanto-occipital dislocation (A–O dislocation), following a motor vehicle accident. (A) Preoperative lateral cervical spine film showing abnormal craniovertebral relationships consistent with AOD. (B) Preoperative midsagittal magnetic resonance imaging with short T1 inversion recovery sequence depicting significant posterior craniocervical soft tissue injury and craniocervical distraction. (C) Postoperative lateral cervical spine film showing occiput–C2 instrumentation with ABT loop (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN), with C1–C2 transarticular screws with posterior occiput–C2 fusion.

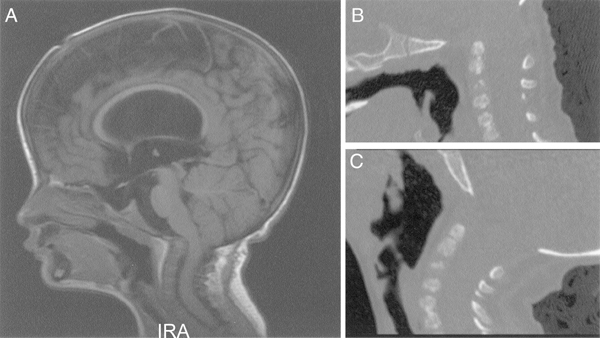

Extremely young patients (such as newborns and those in the infant–toddler age group) with CVJ instability and pathology are generally managed with a custom-fitted external orthosis to provide protection and support until the patient is old enough to undergo operative management safely. As instrumentation and surgical techniques improve, however, it may be possible to provide operative stability in selected cases that obviously require fusion (Figs. 6–2 and 6–3). As time goes on, the strategies and techniques that dictate the management of this extremely challenging patient population will improve.

Surgical Management and Decision Making

This section discusses various scenarios regarding the nature of a given CVJ lesion, its stability and reducibility, its natural history, and the patient’s growth potential.

In general, if the major compressive lesion is from the anterior direction, an anterior approach (usually transoral) should be used, and dorsal fixation should be performed at the same time or as a staged procedure. Posterior compressive lesions may be dealt with by a strictly posterior approach. Lesions that have both anterior and posterior compression may be attacked from both directions and stabilized posteriorly.

Figure 6–3 A 2½ -year-old girl with severe congenital craniocervical instability. (A) Midsagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan showing significant craniocervical distortion and anterior brain stem compression. (B) Midsagittal two-dimensional computed tomographic (CT) reconstruction, with the patient in flexion, showing the severe craniocervical abnormalities. (C) Midsagittal two-dimensional CT reconstruction, with the patient in extension, showing reduction of deformity.

Unstable CVJ lesions must be stabilized at the time of surgery, usually from the posterior direction. Lesions that present with an initially stable CVJ may become unstable postoperatively following either or both removal of the mass and bony decompression and require fusion. Unless addressed at the initial surgery or shortly thereafter, this phenomenon will progress, especially in a vertical direction.

Irreducible lesions that require fusion should be fused in situ, whereas reducible lesions may be fused in their reduced position. Recent data from Larsson et al7 have indicated that in situ posterior instrumentation and fusion alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis can alleviate and potentially improve anterior compressive lesions and symptoms. How this information may apply to pediatric patients with similar inflammatory pathology is unknown.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree