Rejuvenation of the neck often requires more than just a neck lift. Various steps and procedures exist to enhance the surgical technique or overall result. Fibrin sealants can be used to improve the recovery process and obviate the need for drain placement. Chin augmentation can be a critical part of creating a more refined neckline. Submandibular gland excision has been put forth as helpful to the overall aesthetic result. A low and anteriorly positioned hyoid bone creates an unattractive neckline that is difficult to treat. This article focuses on techniques beyond lifting and resurfacing that may enhance neck rejuvenation.

Key points

- •

Chin projection should be evaluated in all patients seeking neck rejuvenation, and augmentation offered if indicated.

- •

Treatment of enlarged or ptotic submandibular glands is more invasive and carries with it significant risks, but is feasible.

- •

Fibrin sealants remove the need for drains postoperatively and help to improve the overall surgical experience.

Introduction

Rejuvenation of the neck often requires more than just a neck lift. A variety of steps and procedures exist to enhance the surgical technique or the overall result. Fibrin sealants can be used to improve the recovery process and are well documented in several recent studies. Chin augmentation can be a critical part of creating a more refined neckline. Other procedures, such as submandibular gland excision, have been put forth by some as helpful to the overall aesthetic result. The position of the hyoid bone also plays an important role in the overall appearance of the neck. This article focuses on techniques beyond lifting and resurfacing that may enhance rejuvenation of the neck.

Introduction

Rejuvenation of the neck often requires more than just a neck lift. A variety of steps and procedures exist to enhance the surgical technique or the overall result. Fibrin sealants can be used to improve the recovery process and are well documented in several recent studies. Chin augmentation can be a critical part of creating a more refined neckline. Other procedures, such as submandibular gland excision, have been put forth by some as helpful to the overall aesthetic result. The position of the hyoid bone also plays an important role in the overall appearance of the neck. This article focuses on techniques beyond lifting and resurfacing that may enhance rejuvenation of the neck.

Fibrin sealants

The standard lifting techniques for the neck (neck lift, lower rhytidectomy) typically require the presence of drains after surgery. Elevation of facial flaps creates a dead space. Drains are used to remove fluid and blood that can collect below the flaps after surgery. Drains, however, are a nuisance for patients and their families, requiring instruction and care. Many patients are reluctant to have surgery because of fear or concern regarding drains. In addition, drains have been associated with infection, pain, and vessel and nerve injury. During consultation before and after surgery, many patients express dissatisfaction with the need for drains.

Fibrin sealants have been introduced in hopes of avoiding the requirement for drains and to improve the recovery process. Fibrin sealants have been used for decades in a variety of medical applications. The fibrin sealant consists of human fibrinogen, human thrombin, and bovine aprotinin. When these are mixed, they stimulate clot formation and the final phase of coagulation ( Fig. 1 ). Continuation of this process forms a stronger clot, with a fully formed fibrin network. This is thought to enhance the healing process and seal capillaries, reducing oozing and bleeding. Studies have shown that fibrin sealants are able to enhance adherence of tissues to the wound bed. What benefits come from that is a more controversial subject.

The first reported use of fibrin glue in facial plastic surgery was by Ellis in 1988. TISSEEL (Baxter Healthcare Corp, Deerfield, IL) was used in a variety of general ear, nose, and throat and facial plastic procedures. As for cosmetic procedures, TISSEEL was felt to be most beneficial in blepharoplasties and facelifts. Ellis noted that although it was no substitute for good surgical technique and maintenance of hemostasis, it was useful in minimizing venous bleeding, oozing, and even tiny capillary arterial bleeding.

Multiple studies followed Ellis’ account, some reporting significant benefits, others less so. One consistent theme noted is the reduction in drain output with the use of fibrin sealants. This was noted by Oliver and colleagues in a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial of the use of fibrin sealants in facelifts. Other studies have followed with TISSEEL and other fibrin sealants that have showed similar findings. It is thought by many that with less drainage, the need for drains is reduced if not eliminated.

What remains a question is if fibrin sealants are helpful in reducing hematomas, seromas, bruising, swelling, and the recovery process in general. Several good studies have shown benefit, whereas others less so. Zoumalan and Rizk found that patients undergoing rhytidectomy treated with fibrin glue and no drains had a lower rate of hematomas than those who had the placement of drains. Similarly, Fezza and colleagues noted patients undergoing rhytidectomy with fibrin sealants had less bruising and swelling and no hematomas. Other studies, such as that by Powell and colleagues, showed positive trends with fibrin sealants, but no statistically significant benefit. Probably most telling of the controversy is the reported experience of Marchac and colleagues. In 1994, Marchac and Sandor reported a reduced rate of hematoma formation in a large series of patients undergoing rhytidectomy with fibrin sealants, but no drains or dressing. In addition, less bruising and swelling were noted in the group receiving fibrin sealants. A decade later, Marchac and Greensmith concluded the theoretical benefit of fibrin sealants was not as great as they had hoped. This second study of 30 consecutive patients showed no difference in bruising, swelling, drain output, or hematoma incidence.

Our experience with fibrin sealants has been with ARTISS (Baxter Healthcare Corp), which is a human-derived fibrin sealant. It received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 for use in adhering autologous skin grafts to surgically prepared wound beds resulting from burns. It differs from TISSEEL in that it has a lower concentration of thrombin (4 IU/mL vs 500 IU/mL), allowing more time for tissue flap positioning. Typically the surgeon has about 60 seconds to prepare and position the flap before polymerization, and thus adherence, begins.

ARTISS received FDA approval as a fibrin sealant for facelift procedures in 2012. Studies for FDA approval showed that although ARTISS reduced drainage volume when used with facelifts, it provided no statistically significant reduction in the incidence of seromas or hematomas.

Patients may undergo either a mini-facelift (short scar facelift) or a full lower facelift to address the neck. A mini-facelift for our patients does not involve direct submental work. Incisions are placed in front of the ear in a posttragal position, postauricularly, and, if needed, across the auriculocephalic angle and back into the hairline for a limited extent. Undermining is carried out as a short flap of 5 to 6 cm. Superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) imbrication is performed. Flaps are then advanced posteriorly in front of the ear and superiorly behind and redundant skin is removed.

A full lower facelift involves direct submental work, typically platysma plication as well as submental liposuction. Incisions are longer, typically into the temporal hairline and posteriorly along the occipital hairline allowing for more skin redraping. Undermining is completed with a long flap that extends 7 to 8 cm anterior and posterior to the ear and is continuous with undermining submentally. An extended superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) imbrication is performed. Flaps are advanced as with a mini-facelift and redundant skin is removed.

Fibrin Sealant Procedure

Following the facelift procedure and prior to closure the ARTISS fibrin sealant is applied.

- •

The packaged syringe sprayer is stored in a freezer and must be thawed prior to use.

- •

The syringe unit containing the thrombin and fibrinogen chambers ( Fig. 2 ) is attached to the Easy Spray Unit ( Fig. 3 ), which provides controlled pressurized air.

Fig. 2

Syringe sprayers.

( Courtesy of Baxter Healthcare, Wayne, PA; with permission.)

Fig. 3

Easy spray unit.

( Courtesy of Baxter Healthcare, Wayne, PA; with permission.)

- •

With the flaps elevated and retracted, ARTISS is sprayed over the raw dissected surfaces as a thin even layer. A distance of 10–15 cm is recommended, but closer application is possible at reduced pressure settings. Typically less than 1 mL per side is used.

- •

The flaps are then immediately placed in position with staples at key points and pressure is applied.

- •

Lap sponges are utilized to provide even pressure and prevent finger marks.

- •

Pressure is applied for 3 minutes after each application to both sides and submentally.

- •

Closure is performed after each application in a layered, plastics fashion.

- •

A light compression dressing is applied to finish the procedure.

Outcomes of Fibrin Sealant

Our own experience with ARTISS has mirrored others who have seen less bruising and swelling and a quicker recovery. We have had no hematomas or seromas in patients receiving the fibrin sealant. At the American Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery 2013 annual meeting, 2 reports, one by Farrior with ARTISS and a second more long-term study with TISSEEL by Caniglia found similar results. Most of our patients receiving ARTISS have been in the mini-facelift category ( Figs. 4 and 5 ); however, we are using the fibrin sealant increasingly on patients with full lower facelift as well ( Fig. 6 ). We believe that fibrin sealants are a beneficial addition to procedures involving rejuvenation of the neck.

Chin augmentation

Although chin augmentation is commonly performed in conjunction with rhinoplasty, it, too, contributes to the contour of the neck. Microgenia, retrognathia, and resorption can create an obtuse cervicomental angle by decreasing the distance between the hyoid and chin. Furthermore, a well-projected chin serves as a focal point for which the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) may be suspended and the skin redraped during a rhytidectomy. Therefore, it is important to recognize any deficiencies of the chin before a neck rejuvenation procedure. For women, the mentum should be 1 to 2 mm posterior to the plane of the lower lip vermilion border and, for men, it should be at or slightly in front of this plane.

There are a variety of techniques used in augmenting the chin. Augmentation with facial implants is popular among facial plastic surgeons. Implants are classified by the source from which they are derived. Autogenous grafts, such as bone and cartilage, are harvested from the patient. Autogenous grafts, however, suffer from limited availability, donor site morbidity, and resorption over time. Homologous grafts, such as cadaveric rib, are harvested from cadavers and are then irradiated to remove pathogens. Homografts yield no donor site morbidity and are widely available, but are plagued by patient fear of disease transmission and also unpredictable resorption. Alloplastic implants are made from synthetic materials. Alloplastic grafts are widely available, avoid donor site morbidity, and do not transmit disease. The ideal alloplastic implant should be inert, noninflammatory, noncarcinogenic, nonallergenic, nonreactive material that is easily obtained, molded, implanted, secured, and removed if needed. The material should be pliable enough to conform to different shapes and resist distortion. It should not cause erosion of nearby structures. A variety of materials are used for alloplastic mentoplasty.

Expanded Polytetrafluorethylene

Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE or Gore-Tex; W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ) was the first biosynthetic material designed for implantation in humans. It is nondegradable, inert, pliable, and easily cut to shape. It has small pores, allowing for fibrovascular ingrowth and stability after placement. Godin and colleagues reviewed 324 cases of ePTFE used in augmentation mentoplasty, and found an overall infection rate of 0.62% and no resorption. On the other hand, Shi and colleagues reported a case of severe bone resorption underneath an ePTFE implant that they attributed to mentalis muscle hyperactivity. Others criticize that ePTFE is too soft and pliable.

Porous Polyethylene

Porous polyethylene (Medpor; Stryker Corp, Kalamazoo, MI) is another commonly used material. It is nonallergenic, nonantigenic, nonabsorbable, highly stable, easy to fixate, and available in a variety of shapes and sizes. Its porous nature allows for fibrovascular ingrowth and stabilization of the graft. Porous polyethylene, however, suffers from poor pliability and therefore may not contour well to the mandible. Niechajev reported no infections in 28 Medpor chin implants and only 3 infections overall using Medpor facial implants. Gui and colleagues reported no infections or alloplastic reactions to the Medpor chin implants in 150 chin augmentation procedures.

Polyamide Mesh

Polyamide mesh (Supramid; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) is an organopolymer related to nylon or polyester fiber. It is flexible, easily cut and shaped, and allows for fibrovascular ingrowth. Polyamide mesh, however, has been found to elicit an intense foreign body response resulting in chronic inflammation. Beekhuis reported generally favorable results in more than 200 patients using polyamide mesh for nasal and chin implants, but did note occasional loss of bulk due to resorption.

Silicone Rubber

Silicone rubber is a popular implant that is commonly used in various parts of the body. It is a nonporous material, therefore it does not allow for fibrovascular ingrowth. A local inflammatory response results in thin fibrous capsule formation around the implant itself. If the implant is mobile, then a seroma can form. If the tissue overlying the implant is thinned, then extrusion may occur. Various reports have found that bone resorption occurred underneath the implant over time. Infection rates were low for both external and intraoral placement of the silicone implant.

Mersilene Mesh

Mersilene mesh (polyamide nylon mesh or polyester fiber; Ethicon) was first introduced in 1950. It is composed of nonabsorbable nylon polyester fibers that are woven into multifilament strands of polyethylene terephthalate. The pore size of the mesh is large enough to allow tissue ingrowth, which helps to secure the implant. Mersilene mesh is inert, noninflammatory, noncarcinogenic, and nonreactive. It has great tensile strength to resist distortion, yet it is pliable enough to conform to the bony skeleton. In addition, it provides a natural appearance and is essentially nonpalpable. Studies by McCollough and colleagues and Gross and colleagues showed that Mersilene is a safe, implantable material with low infection rates.

Our preferred material for chin augmentation is the Mersilene mesh. Here, we describe our approach and technique. The need for chin augmentation first starts with evaluation of the patient. The standard 3 views are obtained in the Frankfort horizontal plane with normal occlusion. Chin projection is evaluated by dropping a vertical line from the lower lip. The depth of the labiomental sulcus is also noted and should be approximately 4 mm posterior to this line. Cephalometric radiographs are generally not needed. Contraindications to augmentation include severe microgenia (requiring >10 mm of projection), shortened mandibular height with lower lip protrusion, severe periodontal disease, preexisting anatomic or functional impairment of the oral sphincter, age younger than 15 years, and prosthetic heart valves or ventriculoperitoneal shunts.

Our technique for creation of the implant is well described elsewhere. The Mersilene mesh is supplied in a single 30 × 30-cm sheet. A 5 × 2-cm template is placed onto the outstretched sheet and the mesh is folded onto itself 9 times to create a rectangular shape that is 10 layers thick. The template is then removed. To create a double implant, an additional step is required. A 5 × 1-cm template is used to create a smaller implant of the same shape and thickness (10 layers). The smaller implant is then sutured on top of the larger implant to create a double implant that is 20 sheets thick. A triple implant is created by adding an additional 5 × 2-cm implant. The implants are sutured together with a 5-0 polyglyconate suture in a running horizontal mattress fashion. The implants are then packaged, labeled, and steam sterilized before implantation.

The Mersilene implant can be placed via an intra-oral or submental approach. Prior to the incision, intravenous cefazolin is administered (for both approaches). In both techniques, the implant is placed between the pogonion and menton, which yields the most natural chin profile. We will first describe the intra-oral approach.

Implant Placement Via Intraoral Approach

Before the incision, intravenous cefazolin is administered (for both approaches).

- •

A 2.5 cm incision is made through the inner aspect of the lower lip at least 1 cm above and parallel to the gingival labial sulcus.

- •

A Freer elevator is used to bluntly dissect over the mandibular symphysis in a subperiosteal plane.

- •

Dissection is carried inferior towards the lower border of the mandible and lateral towards the mental foramen ensuring to stay inferior to the mental nerves.

- •

The appropriate sized implant is selected.

- •

The implant is then cut and trimmed to create a tapered lateral border.

- •

The implant is soaked in a solution of bacitracin (50,000 U) and gentamycin sulfate (80 mg).

- •

The soft tissue is retracted and the implant is placed into position under direct visualization.

- •

Inspection and palpation confirms the proper placement and final chin projection.

- •

The periosteum is closed such that it prevents implant migration.

- •

The incision is closed in layers with the surgeon’s choice of suture technique and material.

Implant Placement Via Submental Approach

- •

For the submental approach, a 2 cm transverse incision is made just posterior to the submental crease.

- •

Sharp dissection is carried down to the periosteum of the mandibular symphysis.

- •

A subperiosteal plane is developed by blunt dissection centrally and laterally, ensuring to not injure the mental nerves.

- •

As with the intra-oral approach, the implant is shaped and placed under direct visualization and confirmed by manual palpation and inspection.

- •

The periosteum is closed to prevent migration of the implant.

- •

The skin is closed in layers.

Post Procedure

- •

After the incision is closed, Mastisol (Ferndale Laboratories; Ferndale, MI) and Micropore tan tape (3M Corp, Minneapolis, MN) is applied to the skin overlying the anterior aspect of the chin.

- •

A circumferential head dressing encompassing the chin is applied using 4×4 inch 6 ply Curity gauze sponges (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) and 4 1/2 inches × 4 1/8 yards 6 ply Kerlix (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) for mild compression and hemostasis.

- •

The dressing is removed the following day.

- •

For the intra-oral approach, the patient is instructed to rinse their mouth with hydrogen peroxide and water following each meal.

- •

All patients are prescribed 500 mg of oral cephalexin twice daily for 5 days.

- •

The patient follows up in 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and each year thereafter.

Outcomes of Surgical Approaches

While the approach is largely based on surgeon preference and comfort, there are potential benefits to each approach. The obvious benefit of an intraoral approach is the lack of an external scar. The malposition rate is lower with this approach due to improved exposure; however, the infection rate is slightly higher. Failure to reapproximate the mentalis muscle can lead to chin ptosis.

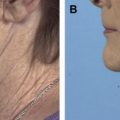

Chin augmentation allows the achievement of a better neckline in patients with microgenia. Benefits can be seen with patients undergoing simply liposuction ( Fig. 7 ), as well as those undergoing a full lower facelift ( Fig. 8 ). Evaluation of chin projection and augmentation when indicated is a critical part of optimal neck rejuvenation.