Actinomycosis, Nocardiosis, and Actinomycetoma: Introduction

Actinomyces and Nocardia are a group of filamentous bacteria belonging to the same class, Actinobacteria, and same order, Actinomycetales. They cause human disease with prominent skin involvement. Microorganisms under this category were wrongly classified as fungi for a long time, because of their tendency to produce branching filaments, mimicking radiating hyphae (from the Greek actino, meaning sun). Their taxonomy is still evolving, resulting in continuous reclassification of different species in old and new families. Anaerobic endogenous Actinomyces, part of our normal respiratory, intestinal, and genitourinary flora, will cause localized suppurative disease with fistula formation that is analogous to the lumpy jaw of cattle. Aerobic environmental Nocardia sp. cause diseases ranging from cellulitis to paronychia to abscesses, with the most striking presentation being a lymphocutaneous, sporotrichoid syndrome. In addition, other aerobic environmental species of Nocardia and Actinomyces will cause one of the two known forms of mycetoma, the actinomycetoma.

The sulfur granule or grain, a clumping of filamentous bacteria seen in infected living tissue, is considered characteristic of the infection by these microorganisms, but is not always present and is also not specific (Table 185-1). Practicing dermatologists should be aware of the various morphologic variants of these diseases, so that measures may be taken to ensure the appropriate culturing techniques required for isolation.

Disease | Actinomycosis | Nocardiosis | Actinomycetoma | Eumycetoma | Botryomycosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clinical pattern | Lump with draining sinuses | Sporotrichoid, cellulitis | Lump with draining sinuses | Lump with draining sinuses | Lump with draining sinuses |

Site | Cervicofacial, thorax, abdomen, pelvic | Extremities (upper > lower) | Feet, back, extremities | Feet mainly | Hand, head, feet |

Source | Endogenous flora | Environment | Environment | Environment | Endogenous and environment |

Most common causative agent | Actinomyces israelii | Nocardia brasiliensis Nocardia asteroides | Nocardia brasiliensis Actinomadura madurae Actinomadura pelletieri Streptomyces somaliensis | Madurella mycetomatis Magnaporthe grisea Pseudallescheria boydii | Staphylococcus aureus Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Presence of grains, clinically or in tissue | Common | Rare (only disseminated) | Always | Always | Always |

Content of grains | Filamentous bacteria | Filamentous bacteria | Filamentous bacteria | Hyphae | Cocci |

Staining | Gram-positive | Gram-positive Weak acid-fast bacillus | Gram-positive Weak acid-fast bacillus (only if Nocardia) | Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott | Gram-positive |

Actinomycosis

|

Described by Israel in 1878, the disease has a worldwide distribution. It is more commonly seen in males, ages 20–60, with females affected at a younger age. In the preantibiotic era, the incidence in the Netherlands and Germany was 1:100,000 inhabitants/year; in the 1970s, the reported incidence in Cleveland, Ohio, was 1:300,000 inhabitants/year, and in 1984, in Cologne, Germany, it was estimated to be 1:40,000 inhabitants/year.1 Recently, an increased incidence of genitourinary actinomycosis has been described in females, related to the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs). Nowadays, there is a tendency of subtle cases with more limited involvement, many of them restricted to the oral cavity. Diagnosis in such circumstances requires a high index of suspicion.

The term actinomycosis implies disease produced by endogenous, anaerobic, or microaerophile, Gram-positive, nonspore-forming bacteria, belonging to the families Actinomycetaceae and Propionibacteriaceae, of the order Actinomycetales; and Bifidobacteriaceae, of the order Bifidobacteriales.1 Their normal habitat is human or animal mucosal surfaces, with considerable host specificity, from the mouth to the upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, and female genital tract. Species known to cause disease in humans include A. israelii, Actinomyces naeslundii, Actinomyces gerencseriae, Actinomyces viscosus, Actinomyces odontolyticus, and Actinomyces meyeri, as well as Propionibacterium propionicum and Bifidobacterium dentium. The disease in most cases is mixed with other microorganisms sharing the same habitat, so it should be considered a synergistic infection, with the Actinomyces playing the role of guiding organism, defining the course, the symptoms, and the ultimate prognosis. Accompanying organisms may vary in number, from one to nine different species, and may include coagulase negative staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, α- and β-hemolytic streptococci, microaerophile and anaerobic streptococci, Fusarium and Bacteroides spp., and even Propionibacterium sp. other than P. propionicum.1 This concomitant flora may be in part responsible for the disease course. If pyogenic bacteria are involved, such as S. aureus or β-hemolytic streptococci, the lesion will be acutely inflammatory and painful. If, on the contrary, anaerobes predominate, the course will be subacute and insidious. A distinctive more chronic course is seen when A. israelii or A. gerencseriae is accompanied by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. In recent years, with better culturing techniques, more than one Actinomyces have been isolated from one single lesion in several patients, stressing the possibility that single bacterial isolation, common in the past, was a technical artifact.

The infection has its portal of entry at a break on a mucous membrane. Most cervical and facial cases originate from periapical abscesses or after dental procedures. Actinomyces bacteremia seems to occur quite commonly after dental procedures.2 Thoracic cases represent involvement of the chest wall by continuity either from pleural or lung disease acquired by obstruction or aspiration. The same mechanism of spreading applies to disease of the abdominal wall, secondary to gut or genital pathology, following appendicitis, diverticulitis, surgery, or trauma. Perineal disease occurs as a consequence of involvement of the internal organs of the pelvis, often secondary to use of an intravaginal device or IUD. The only exception to the endogenous origin of the infection is hand involvement that follows fist or bite trauma.3

In tissue, the bacteria cluster in filamentous aggregates, the so-called sulfur granules (grains; see Table 185-1). They are commonly surrounded by acute and chronic inflammation, usually neutrophils, granulation tissue, and fibrosis. Granuloma formation is unusual. The fistula formation may give way to drainage of granules, their presence at once should not be considered specific for this disease.

Actinomycosis should always be suspected when dealing with one of three features: (1) a mass-like inflammatory infiltrate of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, (2) sinus formation with drainage, and (3) a relapsing or refractory clinical course after short-term therapy with antibiotics. Actinomycotic granules may be seen macroscopically. Although most patients are immunocompetent, a recent series underlies the importance of Actinomyces as an emerging pathogen in patients with chronic granulomatous disease.4

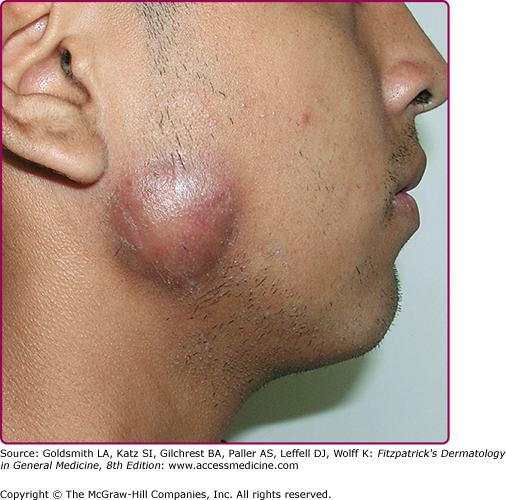

Cervical actinomycosis is the most frequent form of disease,5 accounting for approximately 55% of cases. Commonly, there is a history of poor dental hygiene, dental or periodontal disease, dental procedure, surgery, or penetrating trauma through the oral mucosa. Most of the infections start as a periapical abscess. The most common location is on the jaw angle and high cervical area (60%), followed by the cheek (16%), the chin (13%), and less commonly, the temporomandibular joint and the retromandibular area. The lesion starts as a solid mass in any of those locations, and initially may be confused with a neoplastic process (Fig. 185-1). It may progress to form recurring abscesses and later will spread to adjacent structures, not respecting anatomic planes. Propagation to lymph nodes is uncommon but eventually may involve the orbit, cranium, spine, and even vascular structures. The lesion is sometimes reported as painless, but pain may be present, as well as fever and leukocytosis. With extension to the skin surface, sinus tracts appear (Fig. 185-2). The overlying skin may have a purplish red hue. Trismus may develop. Bone involvement, mostly of the jaw, is present in 10% of cases. More limited disease may produce a mass or an ulcer, affecting any structure in the mouth or the nasopharyngeal region. Extension to the ear may present as chronic otitis media or mastoiditis. In addition to orbital involvement, there are reported cases of lacrimal canaliculitis and endophthalmitis.

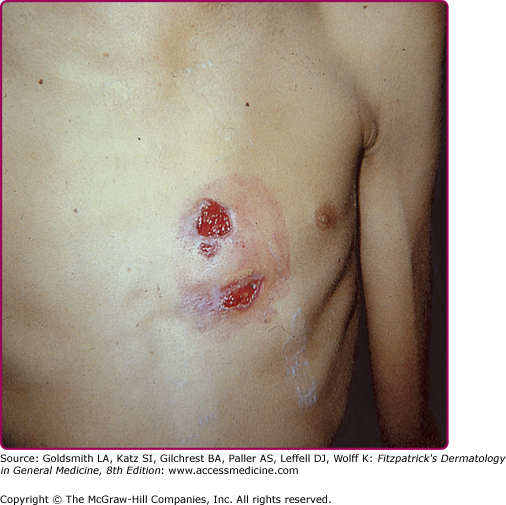

Thoracic actinomycosis comprises 15% of cases. The common source of infection is the aspiration of microorganism from the oropharynx, although other routes are possible, such as propagation of cervicofacial disease to the mediastinum. The disease may involve the lung, pleura, mediastinum, and chest wall. The course is indolent, with chest pain, fever, weight loss, cough, and less frequently, hemoptysis, mimicking tuberculosis. Radiologically, the disease will present as a mass or pneumonia, with pleural involvement by continuity. Relevant to dermatologists, up to 26% of cases will have chest wall involvement5 with the developing of a cutaneous abscess and sinus formation (Fig. 185-3). Parenchymal, pleural, and chest wall disease occurring together will make actinomycosis a most likely diagnosis. Mediastinal actinomycosis may show either as anterior chest wall disease (rarely sternal involvement), or paraspinal abscess. Involvement of breast tissue and breast implants has also been described.

Abdominal actinomycosis represents about 20% of all cases. It is as a consequence of spreading from the gastrointestinal tract or from the female genital tract. Appendicitis and diverticulitis are common precipitating events. Any organ in the peritoneal cavity may be affected; by continuity, the disease may spread to the abdominal wall. An inflammatory mass may appear in the skin surface of the abdominal region or the perineum, with later development of sinuses. In the perianal area, multiple abscesses and fistula formation may occur. From there on, spreading to buttocks, thigh, scrotum, or groin may follow.

Primary pelvic disease most commonly originates from ascending infection from the female genital tract and less commonly from abdominal disease. The role of IUD as a risk factor has been well-established and infection is usually associated with prolonged use, 8 years on average.

Punch or fist actinomycosis represents a particularly uncommon but interesting clinical presentation. It usually follows blunt trauma of a closed fist against an adversary’s mouth; similar findings may originate from a human bite. It usually involves the proximal phalanges and metacarpal bones. First a soft tissue infection, it will eventually spread to the bony structures. Grains are commonly seen in this particular form.

Actinomycosis of the central nervous system (CNS) may present as brain abscess, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, subdural empyema, actinomycoma, and spinal abscess. It is usually secondary to hematogenous spread.

Laboratory tests considered useful include direct examination of draining material, culture, and biopsy. Direct examination will show the presence of filamentous Actinomyces on Gram stain. The isolation of Actinomyces in culture should be considered diagnostic, if coming from a sterile site. However, positive culture rates are as low as 35% in some series. The processing should be done in anaerobic conditions, and when all techniques available today are used, the percentage of isolates that cannot to be identified is as low as 2.8%.1 Needle aspiration has been recently reported as an additional diagnostic procedure.6

The best material to culture is tissue, pus, or microscopic granules, and avoidance of any antibiotic treatment is recommended. Appropriate culture media include thioglycolate with 0.5 sterile rabbit serum at 35°C (95°F) for 14 days. Colonies may appear within 5–7 days, but up to 2 weeks may be required. A. israelii classically will produce a “molar tooth” colony on agar and will look clumpy on broth. A. odontolyticus colonies are red or rusty in color. Actinomyces are indole negative. The microbiologic identification of different species occurs only in a minority of cases. Tests for urease, catalase, gelatin hydrolysis, and fermentation of cellobiose, trehalose, and arabinose may also be performed, as well as gas liquid chromatography, indirect immunofluorescence testing, and sequencing or restriction analysis of amplified 16S ribosomal DNA.

The presence of granules, either microscopically or macroscopically, is very relevant, especially if obtained from tissues not connected to mucosal surfaces. Grains are usually yellow (hence the name sulfur granules), but can be white, pinkish gray, gray, or brown. In tissue samples, special stains, such as Brown–Brenn, Gram, Giemsa, or Gomori stains, are required to demonstrate filamentous structures. The number of grains is usually scanty: only one single granule was identified from 25% of specimens in a study of 181 cases.5 The microscopic examination of the granules may reveal the Splendore–Hoeppli phenomena, a rim of eosinophilic material surrounding the granules in tissue sections. The lack of staining with Fite-modified acid-fast stain separates Actinomyces from Nocardia sp. Eumycetoma granules stain positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Gomori stains, whereas granules from Botryomycosis should show clumps of bacteria. Direct immunofluorescent staining is available for some species, including A. israelii (see Table 185-1).

Depending on the site affected, the differential diagnosis will include infections such as tuberculosis, noninfectious inflammatory processes such as hidradenitis or inflammatory bowel disease, and neoplasia (Box 185-1).

Most Likely

|

Consider

|

There is general agreement that the treatment of actinomycosis requires high-dose antibiotics to be given for a long period. The treatment of choice is penicillin G, 18–24 million units intravenously for 2–6 weeks, followed by oral penicillin or amoxicillin, to be given for 6–12 months. Cervicofacial disease or any more limited disease can receive a shorter course of therapy. A good rule to follow is to treat until there is full resolution of clinical disease. Alternative treatment for those allergic to penicillin includes tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Imipenem has been used successfully as short-term therapy. Chloramphenicol is the alternative to penicillin in cases of CNS involvement. Risk factors for death or relapse include duration of disease longer than 2 months, lack of antibiotic therapy or surgical therapy, and needle aspiration rather than open drainage or excision.

With early diagnosis and more limited disease, as compared to the bulky disease of the past, treatment can be shorter: 30 days for cervicofacial disease and 3 months for pelvic or thoracic disease.7 Periapical actinomycosis can be successfully treated with curettage and 10 days of antibiotic therapy.

Surgery is indicated for bulky disease involving the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and CNS. It should be directed to resection of necrotic tissue, excision of sinus tracts, draining of empyemas and abscesses, and curettage of bone, always accompanied by antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotics effective against synergistic microbes that accompany the Actinomyces can reasonably be included in the initial therapy.

Nocardiosis

|