Acquired Perforating Disorders: Introduction

|

Introduction

Acquired perforating disorders represent a group of separately identified cutaneous disorders that occur in adult patients, most often in the setting of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Kyrle’s disease (KD), acquired elastosis perforans serpiginosa (AEPS), acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC), and perforating folliculitis (PF) were previously considered distinct disorders.2–5 Given their shared clinical and histopathological characteristics, these four disorders are now classified under the umbrella term of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).1 APD is characterized clinically by the presence of umbilicated papules and/or nodules with a central keratotic plug or crust and histologically by the transepidermal extrusion of dermal components (collagen, elastin, and/or fibrin).6 Although some cases may exhibit clinical and histological characteristics that typify one of the four classically recognized disorders, use of the comprehensive term APD is encouraged.

Epidemiology

Kyrle, in 1916, first described KD in a young diabetic woman and termed it hyperkeratosis follicularis et parafollicularis in cutem penetrans.5 In 1953, Lutz published the initial description of elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) as keratosis follicularis serpiginosa.7 The first case of AEPS associated with CKD was identified in 1986 by Schamroth, Kellen, and Grieve.2 Mehregan, Schwartz, and Livingood reported the earliest description of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) in 1967, and the first case associated with DM was recognized by Poliak et al in 1982.3,8 PF was originally described by Mehregan and Coskey in 1968.4 In 1989, Rapini, Heber, and Drucker recognized the common clinical and histopathologic characteristics of these disorders and introduced the term acquired perforating dermatosis.1 Various terminology has been used in the literature to refer to APD (Table 69-1).

Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis9 Hyperkeratosis follicularis et parafollicularis in cutem penetrans5 Hyperkeratosis penetrans10 Keratosis follicularis serpiginosa7 Kyrle’s disease11 Kyrle-like lesions12 Perforating disorder13 Perforating folliculitis8 Perforating folliculitis of hemodialysis14 Reactive perforating collagenosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) and renal failure15 Uremic follicular hyperkeratosis16 |

APD occurs worldwide without gender predilection.17 The most common systemic diseases associated with APD are CKD and DM. APD has been documented in 4.5%–10% of hemodialysis patients in North America and in 11% of a dialysis population (both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis) in Great Britain.17,18 APD has also occurred in patients with CKD who are not undergoing dialysis as well as those who have received renal transplants. The most common cause of CKD among APD patients is diabetic nephropathy.18 Table 69-2 lists less commonly reported associated conditions. APD has rarely been associated with the use of certain therapeutics, including tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors, indinavir, and sorafenib.44–46 A predominance of blacks among hemodialysis patients with APD has been reported in one study, but not confirmed in others.11 AEPS is well recognized as a potential adverse effect of prolonged d–penicillamine therapy.47 AEPS has also been reported in patients with CKD in the absence of penicillamine exposure or other associations.2

Common Associations Chronic kidney disease Diabetes mellitus (insulin-dependent and noninsulin-dependent) |

Rare Associations Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)21,22 Atopic dermatitis25 Cutaneous cytomegalovirus infection26 Hyperparathyroidism9 Liver diseases (hepatitis C, hepatitis B, steatohepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis)6,27 Lupus vulgaris28 Myelodysplastic syndrome29 Malignancy (Hodgkin lymphoma, mixed histiocytic–lymphocytic lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma)30–37 Mikulicz’s disease38 Neurodermatitis9 Poland syndrome39 Primary sclerosing cholangitis40 Pulmonary aspergillosis41 Pulmonary fibrosis25 Salt water application13 Thyroid disease (hypothyroidism, sick euthyroid syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis)9,27,42 Vitamin A deficiency43 |

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The precise etiology and pathogenesis of APD are unknown. APD pathology likely involves a complex interaction between the epithelium, connective tissue, and inflammatory mediators. Superficial trauma to the epidermis may be the primary inciting factor in susceptible patients.8 Predisposing conditions include vasculopathy/angiopathy (related to DM), microdeposition of exogenous materials within the dermis (including calcium salts and silicon, pertinent to the increased frequency of APD in dialysis patients), and epidermal or dermal change related to metabolic derangements including vitamin A deficiency.13,18,43,48,49

Given APD’s common association with CKD, scratching due to chronic pruritus has been thought to lead to microtrauma and subsequent transepidermal elimination of dermal components. Koebnerization, predominant localization to trauma-prone areas, and resolution of APD lesions with discontinuation of manipulation/trauma support this mechanism.6 Diabetic vasculopathy has been proposed as an additional predisposing factor for APD in DM patients by creating a relatively hypoxic environment in which trauma from scratching causes dermal necrosis. The finding of PAS-positive thickening of vessel walls in the upper dermis of diabetic patients with APD48,50 supports this hypothesis, but has not been noted in all studies.6,51 Imbalances in fibronectin, transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF-β3), and matrix metalloproteinases in APD lesions have also been demonstrated; these molecules are essential to normal epithelial differentiation and wound healing, and their aberration may predispose to the development of APD lesions.48,51,52 In AEPS, it is hypothesized that penicillamine alters dermal elastic fibers in affected patients.53 Elastic fiber abnormalities, including “bramble bush-appearing” fibers of variable thickness and increased numbers of fibers in the papillary and reticular dermis, have been described in patients with penicillamine-induced AEPS.54

Clinical Findings

Most patients report lesional pruritus, ranging from mild-to-severe and intractable, of skin lesions. Lesions may also be painful.6

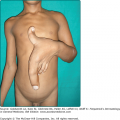

APD characteristically manifests as round, umbilicated, skin-colored, erythematous or hyperpigmented papules and nodules with a central crust or keratotic plug, predominantly involving the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the trunk (Fig. 69-1). Lesions less commonly involve the face or scalp. In rare cases, purple annular plaques or pustules mixed with papules have been observed. Some lesions may be follicular (PF) (Fig. 69-2). AEPS lesions exhibit papules in a serpiginous configuration, often with central atrophy, and typically occurring on the neck, trunk, and extremities (Fig. 69-3). Scratching can lead to koebnerization with linear umbilicated papules arising in excoriated skin.

Although most common in patients receiving hemodialysis, especially for diabetic nephropathy,18 APD has also been seen in CKD patients without hemodialysis or who have undergone renal transplantation. Table 69-2 lists medical conditions that are less often associated with APD.

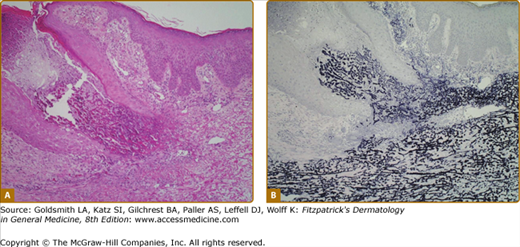

The diagnosis of APD is based on clinical and histopathologic findings. Folliculitis and prurigo nodularis may occur concomitantly, especially in patients with CKD; multiple biopsies should be taken if lesions show different clinical morphologies. APD is characterized histologically by transepidermal elimination of dermal material through an epidermal invagination, which may be follicular or perifollicular. Lesions typically demonstrate a central keratotic plug with crusting or hyperkeratosis; parakeratosis is variable. Within the dermis surrounding the perforation, there is often a focal inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils predominating in early lesions and lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells present in older lesions.

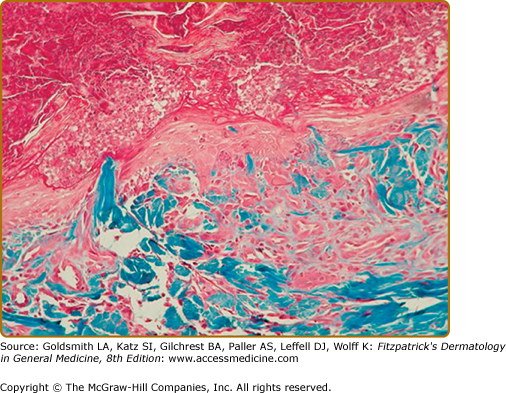

The four initially identified acquired perforating disorders [(1) RPC, (2) AEPS, (3) KD, and (4) PF] were classically differentiated histopathologically on the basis of the nature of the eliminated dermal material. In RPC, collagen bundles are detected within the plug (Fig. 69-4); in AEPS, elastic fibers are instead noted (Fig. 69-5). In KD, amorphous dermal material and/or keratin comprise the extruded material. PF is characterized by perforation of the follicular epithelium by degenerating collagen and extracellular matrix (Fig. 69-6). Clear identification of the eliminated material may be impossible and, in addition, multiple substances (i.e., collagen and elastic fibers) may be simultaneously detected, reinforcing the clinical and histopathologic overlap within APD.