8 Acquired cranial and facial bone deformities

Synopsis

Treatment of acquired cranial and facial bone deformities begins with a thorough physical examination prior to radiologic studies.

Treatment of acquired cranial and facial bone deformities begins with a thorough physical examination prior to radiologic studies.

Access incisions must allow visualization and exposure of the entire defect.

Access incisions must allow visualization and exposure of the entire defect.

Surgical treatment must follow Tessier’s principles of subperiosteal exposure, judicious use of autogenous bone grafts, and rigid fixation.

Surgical treatment must follow Tessier’s principles of subperiosteal exposure, judicious use of autogenous bone grafts, and rigid fixation.

Alloplastic materials are to be avoided if possible.

Alloplastic materials are to be avoided if possible.

Late presentation of acquired deformities may require an osteotomy through the defect site prior to reduction.

Late presentation of acquired deformities may require an osteotomy through the defect site prior to reduction.

Introduction

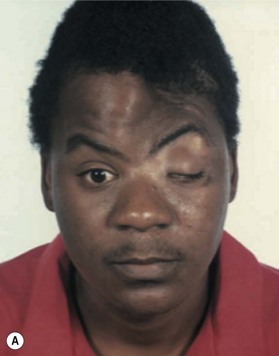

The various causes of acquired deformities of the facial skeleton include trauma, infection, and surgical or radiotherapeutic treatment of neoplasia. The surgical treatment of these acquired deformities has changed radically during the past three decades as a result of advances in the subspecialty of craniofacial surgery. Craniofacial surgery developed almost entirely from the work of Paul Tessier, who revolutionized facial skeletal surgery with his seminal work regarding treatment of congenital malformations, such as Crouzon disease,1 Apert syndrome,2 Treacher Collins–Franceschetti syndrome, vertical orbital dystopias, and orbital hypertelorism.3–8 The basic principles Tessier stressed when operating on the facial skeleton include the following9:

Key points

• Complete subperiosteal exposure of the areas of interest through coronal, lower eyelid, or intraoral incisions.

• Repositioning misaligned segments of the craniofacial skeleton with rigid fixation and interposed autogenous bone grafts to provide consolidation of the structure.10 Onlay “camouflage”grafts are to be avoided because they do not provide a three-dimensional correction of the entire deformity.

• Utilizing only fresh, autogenous bone grafts, obtainable from the ribs, anterior and posterior ilium, tibia, and the skull.11,12 There is little place for bone substitutes, whether alloplastic materials or cadaver bone, in craniofacial reconstruction.13

• If a structure is not present to be repositioned, it can be constructed in situ or constructed and then moved to the proper location.

• The once forbidden boundary zone between the cranial cavity and the midface can safely be transgressed if proper care is taken in its reconstruction. Regular and frequent collaboration between the plastic surgical and neurosurgical members of a craniofacial team decreases the risks associated with a transcranial approach.

• Other members of a craniofacial team, such as ophthalmologists and orthodontists, will need to be involved in the treatment of acquired deformities, just as for congenital malformations.

Basic science/disease process

Access incisions

Coronal incisions

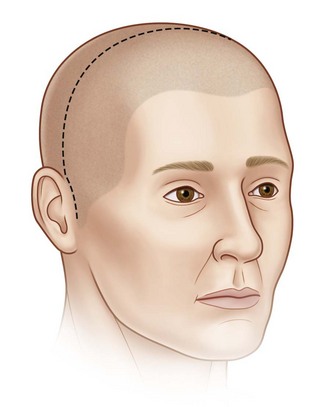

Coronal incisions should be made at least 3 cm behind the anterior hairline, almost at the vertex. The incision is carried to a point just above the anterior attachment of the ear, where a small cutback of 8–10 mm is made in the direction of the lateral canthus, allowing the coronal flap to be turned forward without tension. Incisions close to or along the anterior hairline can be noticeable, and it may be difficult or impossible to improve these scars in areas of alopecia. The dissection is carried out in a supraperiosteal plane to the level of the supraorbital ridge, where it then becomes subperiosteal. The superficial temporal fascia (STF) is generally divided, exposing the deeper temporal fascia upon approaching the zygomatic arch and malar region. The temporalis muscle should be elevated separately from the scalp and resutured to the lateral orbital rim, anterior temporal crest, and posterior portion of the coronal incision, maintaining its original tension upon closure of the incision. The STF should also be resuspended at the time of closure. After the temporal muscle has been sutured back into position under proper tension, a suture is taken from near the lateral canthal raphe and passed through the temporal aponeurosis to reposition the lateral canthus properly (Fig. 8.1).

Lower eyelid incisions

The lower eyelid, inferior orbital rim, and orbital floor can be accessed through either the conjunctiva14or the lower eyelid.15 If a cutaneous approach is used, it should be lower in the eyelid, beneath the tarsal plate, rather than in the immediate subciliary area16 in order to avoid postoperative ectropion.

Intraoral incisions

Upper buccal sulcus incisions should have an adequate inferior mucosal cuff for subsequent closure. The infraorbital nerve should be protected and the buccal fat pad avoided during dissection. The entire mandible up to the sigmoid notch and inferior 1 cm of the coronoid process and condyle are accessible through a lower buccal sulcus incision.17

Bone grafts

The preferred donor area for cranial grafts is the right parietal area in right-handed patients.18 When large grafts are required, the craniotomy can be extended anteriorly beyond the coronal suture and posteriorly into the occipital region. If additional bone is required, the opposite parietal region may be utilized. The harvested bone should be slightly larger in dimension than the area to be corrected. Each graft can be split through the diploic space to give two segments of equal dimensions. The inner table is replaced in the donor area with one of the segments. A defect several millimeters in width will be present, varying with the thickness of the craniotome blade. This defect is placed posteriorly and filled in with small bone chips, slivers, and bone dust and covered with a pericranial flap.19 The bone graft for the defect is tailored exactly to the defect. On occasion, it is good to enlarge the defect slightly by burring back to healthy bone. Fixation with wires, not miniplates, is preferred (Fig. 8.2).

The exception to the rule of utilizing cranial bone as the primary donor site is iliac bone, with rib used only as a last resort. Iliac bone provides an excellent orbital floor because of the thin cortical floor with malleable cancellous bone that is rigid enough to support the globe. Also, iliac bone is an excellent choice when large amounts of cancellous bone are required, such as for obliterating a frontal sinus (Fig. 8.3).

Treatment/surgical technique

Treatment of specific defects

Cranium

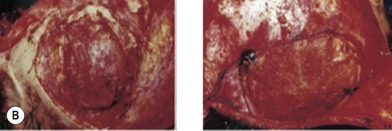

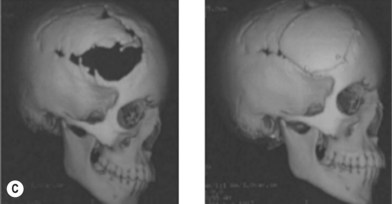

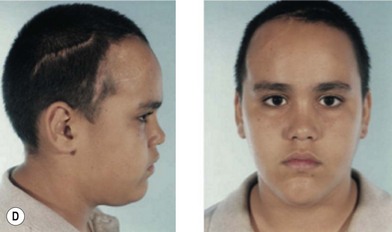

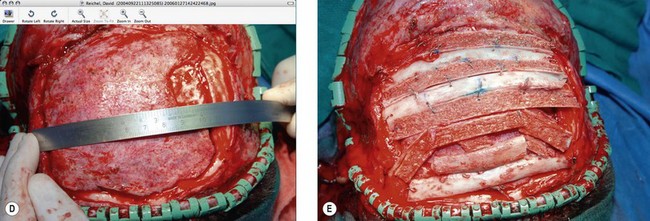

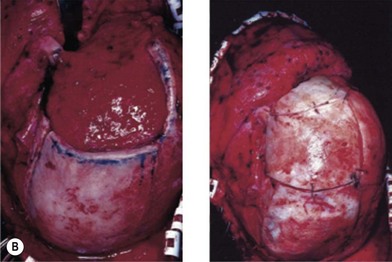

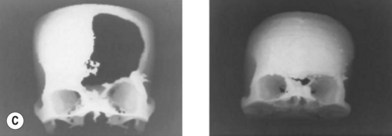

Cranial defects greater than half the thickness of the skull in patients older than 2 years of age should be repaired. In children younger than 2 years of age they often spontaneously ossify and do not require treatment. Cranial bone is the material of choice for most cranioplasties due both to the quality of bone and proximity to the field of operation.20 In the authors’ experience, the youngest patient with a cranial bone that can be successfully split ex vivo is between 3 and 4 years of age. Good results can also be obtained with split rib (Fig. 8.4). Rib grafts can be used from the age of 4–5 years, depending on the size of the patient.

Near the frontal sinus, only autogenous bone should be used.21 If there is a full-thickness cranial defect near the frontal sinus, the sinus should be cranialized; if the posterior wall of the sinus is intact and the nasofrontal duct appears to be blocked, all mucosa should be removed and the sinus filled with autogenous cancellous grafts (Fig. 8.5).22

Nose

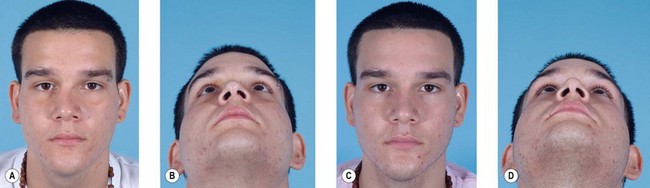

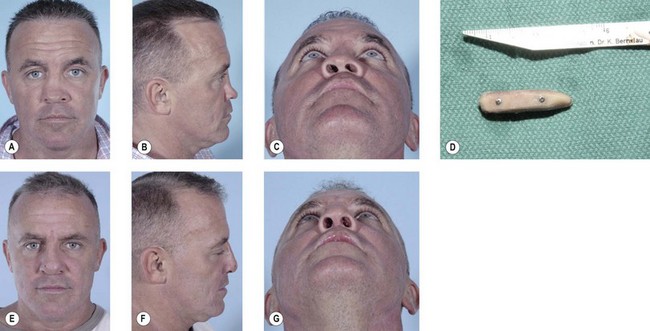

This region involves the nasal bones, cartilaginous and bony septum, and the upper lateral cartilages. Minimally displaced fractures can often be treated with closed reduction and placement of nasal splints (Fig. 8.6). Comminuted fractures require an open rhinoplasty approach and usually require placement of an autogenous bone graft.23–28 This approach makes it possible to separate the alar cartilages and then replace them over the nasal bone graft. Bone grafts for a depressed dorsum are simply placed into an appropriate pocket after dissection of the skin alone. In general, the bone graft is not rigidly fixed in place; care must be taken that the posterior portion of the bone graft is flat to avoid shifting of the graft. Making bilateral nasal vestibular incisions also helps provide an appropriate pocket so that the graft will remain in the center of the nose. If a graft does shift in the postoperative period, it can often be repositioned and maintained with a percutaneous K-wire, placed under local anesthesia, and maintained in position until consolidation of the bone graft occurs (Fig. 8.7).

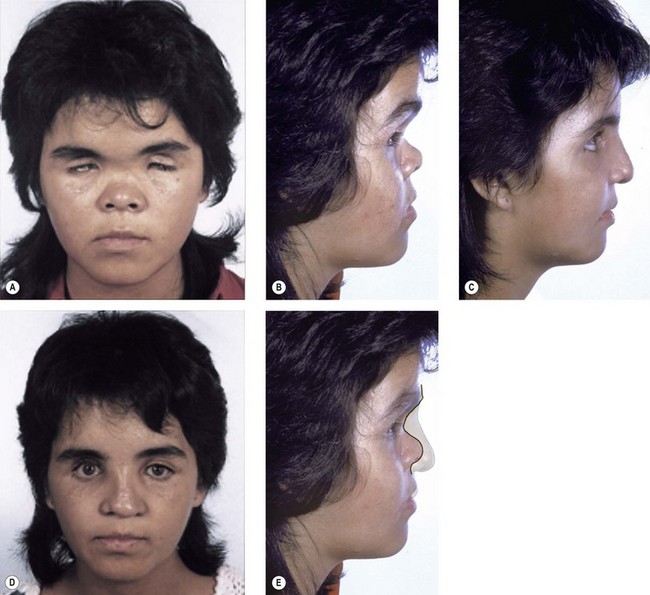

If substantial lengthening (>1 cm) of the nose is required, such as in Binder syndrome29 or posttraumatic nasal foreshortening, dissection of the skin alone is not sufficient. The lining needs to be lengthened as well. Tessier et al. have shown that considerable lengthening can be obtained, even in congenitally short noses, by dissecting the lining from beneath the nasal bones all the way back to the pharynx.30 Another approach is purposely to section the lining (and bone) at the nasofrontal area, as in a Le Fort III osteotomy.31

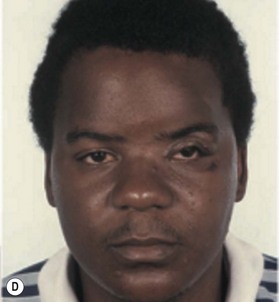

The undersurface of the bone graft may be exposed to the nasal cavity, but healing proceeds uneventfully, as it does in a Le Fort III, over bone grafts exposed to the maxillary sinus, as with a Le Fort I, and over orbital floor bone grafts (Fig. 8.8). This type of procedure would not be applicable to the contracted, foreshortened nose that is associated with sustained cocaine use. Here the lining is either altogether absent or chronically granulating and infected. Before a nasal bone graft can be added, nasal lining must be provided by bringing in tissue from other areas, such as nasolabial, forehead, or buccal sulcus flaps.32

Nasoethmoid area

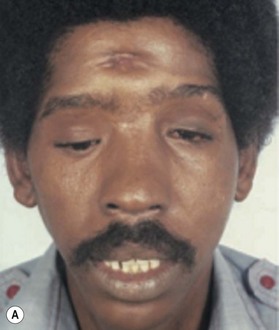

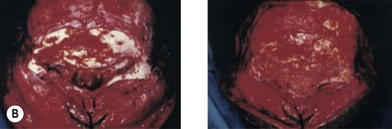

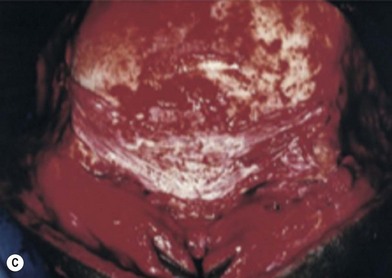

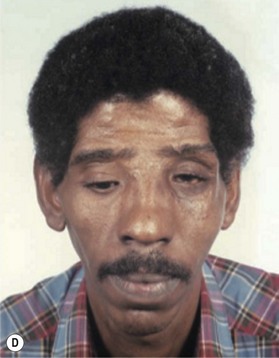

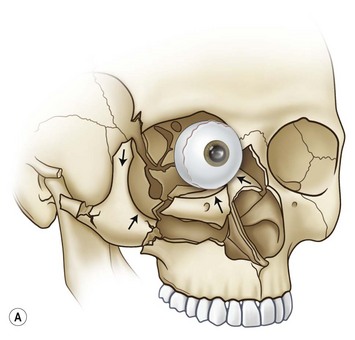

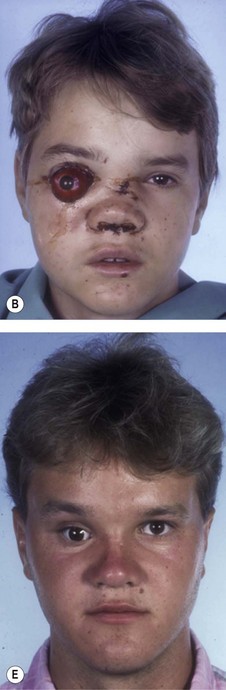

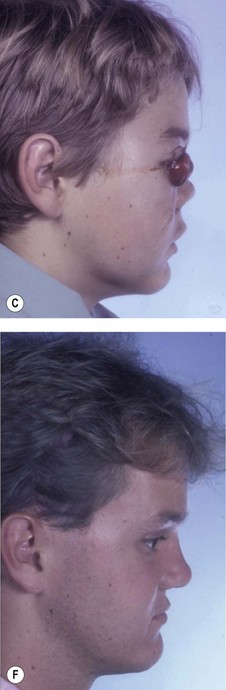

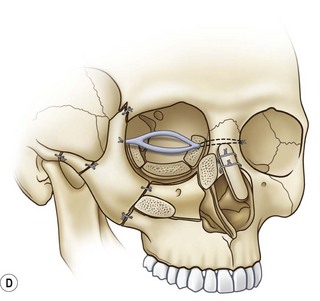

Fractures in this region are often referred to as naso-orbital–ethmoid fractures, although the ethmoidal involvement, by definition, involves the orbit. Telecanthus, as a result of lateral displacement of the medial orbital walls and nasal foreshortening, is commonly seen after these fractures. One must resist the temptation to treat this conservatively with packing alone, as this pushes the structures further in, adding to the nasal foreshortening. A coronal incision should be used for adequate exposure unless a large facial laceration provides excellent exposure. Correction of telecanthus secondary to displaced bone fragments with the medial canthal tendons still attached can often be accomplished by anatomic reduction of the bone segments, without having to detach the tendons and perform a transnasal medial canthopexy.33,34

If the medial canthal tendon has been detached, a transnasal canthopexy must be performed. Some overcorrection of the medial wall segments is desirable, as in the correction of orbital hypertelorism. If there is significant loss of substance in the medial orbital wall, it may be necessary to perform a primary bone graft and medial canthopexy. The nasal dorsum will usually require a bone graft to repair the foreshortening resulting from the fracture (Fig. 8.9).