Abnormal Responses to Ultraviolet Radiation: Idiopathic, Presumed Immunologic, and Photoexacerbated

Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure divide into four categories (Table 91-1): (1) acquired idiopathic, presumed immunologic; (2) DNA repair defect disorders; (3) chemical and drug photosensitivity, including the porphyrias; and (4) photoexacerbated dermatoses not caused directly by UVR. The first and last categories and an approach to assessing photosensitivity are covered in this chapter. The other categories are covered in other chapters in this book. Diagnosis of photodistributed eruptions is discussed in Box 91-1 and Figure 91-1, and the entities are discussed in the following sections.

|

|

Acquired Idiopathic, Probably Immunologic Photodermatoses

|

Polymorphic light eruption (PMLE) is common worldwide, but thought to occur more frequently in temperate latitudes and rarely in equatorial latitudes. However, a large-scale cross-sectional study has revealed no latitudinal gradient in Europe.1 This study estimated an overall suspected lifetime prevalence of 18% among Europeans. Previous reports indicate a prevalence of 10%–15% among North Americans2 and southern Britons,3 and 5% among southern Australians.3 Women are affected more than twice as frequently as men.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also influences the risk of developing PMLE, with the highest prevalence in people with skin type I and the lowest prevalence in people with skin type IV or higher.1

A delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to a sunlight-induced cutaneous photoantigen was first suggested as the cause of PMLE in 1942, based on the delay between UVR exposure and onset of the eruption, as well as on its lesional histologic features.4 In normal skin, UVR is known to induce a transient state of immunosuppression by depleting epidermal Langerhans cells and by promoting the release of immunosuppressive cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-10. In patients with PMLE, the immunosuppression normally associated with UVR is diminished substantially. It is thought that this creates an environment in which hypersensitivity responses to one or more photoinduced neoantigens is permissible. The notion that PMLE represents a DTH response is supported by histopathologic, molecular, and epidemiologic data.

Histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens from lesions of PMLE induced by solar-simulated radiation demonstrates the consistent appearance within hours of a T-cell dominated perivascular infiltrate that peaks by 72 hours. CD4+ T cells are most numerous in early lesions, whereas by 72 hours CD8+ T cells predominate, perhaps abolishing the response.5 Increased numbers of epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal macrophages are also present. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that neutrophil infiltration into the skin following UVB irradiation is deficient, leading to impaired IL-4 and IL-10 release.6 Whereas a Th2 cytokine milieu is favored in normal skin following irradiation, a Th1 cytokine profile is favored in patients with PMLE.7

Molecular studies have revealed increased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on keratinocytes overlying the perivascular infiltrate in PMLE,8 as has been noted in DTH reactions but not in irritant contact dermatitis or after the UVB (290–320 nm) irradiation of normal skin.9

More recently, the induction of allergic contact sensitivity to dinitrochlorobenzene after solar-simulated irradiation of sensitization sites has been shown to occur more easily in PMLE patients than in normal individuals,10,11 which suggests that sensitization to a putative UVR-induced cutaneous antigen may also be easier during disease-inducing exposure. On the other hand, elicitation of allergic contact responses to dinitrochlorobenzene in previously sensitized PMLE patients and normal individuals were equally suppressed by irradiation,12 which explain the frequent development of immunologic tolerance, often called hardening or desensitization, as summer progresses or during prophylactic phototherapy. In fact, normalization in the depletion of epidermal Langerhans cells in response to UVR has been observed in patients with PMLE after undergoing therapeutic hardening.13

Finally, epidemiologic studies also point to hypersensitivity in patients with PMLE. The prevalence of PMLE is much lower in patients with skin cancer, suggesting that UVR-induced immunosuppression that may allow the persistence of malignant cells also inhibits hypersensitivity to photoantigens.14 Also, PMLE is quite uncommon in iatrogenically immunosuppressed transplant recipients, occurring in only 2% of this population.15

The photoinduced neoantigens that initiate PMLE have not been identified, but several molecules may play roles, even in a single patient. The altered molecule(s) itself may hypothetically become antigenic directly by UVR, or secondarily through UVR-induced free radicals that modify nonantigenic peptides in such a way that they become antigenic. Of course, both mechanisms may even take place simultaneously.

UVA radiation (320–400 nm) usually seems more effective than UVB (290–320 nm)12,16 at initiating PMLE. In one study, UVA irradiation elicited the eruption successfully in 56% of patients exposed to UVA or UVB daily for 4–8 days, in 17% of those exposed to UVB, and in 27% of those exposed to both.17 However, other reports have suggested that UVB radiation may be implicated in up to 57% of patients. Therefore, it could broadly be said that approximately 50% of PMLE patients seem sensitive to UVB radiation and 75% to UVA, including in each case approximately 25% who are sensitive to both. Even visible light may be responsible on rare occasions.18 As a result, paradoxically, patients may note that the use of sunscreens, which tend preferentially to remove UVB while transmitting some UVA and all visible light, may even have a PMLE-enhancing effect if exposure times are lengthened. There is most likely genetic predisposition to PMLE,19 but the intensity of initial UVR exposure may also be important in such predisposed individuals.

PMLE usually has onset within the first three decades of life and affects females two to three times more often than males. It occurs in all skin types and racial groups, but is more common in Caucasians. A positive family history is present in about a fifth of patients.19

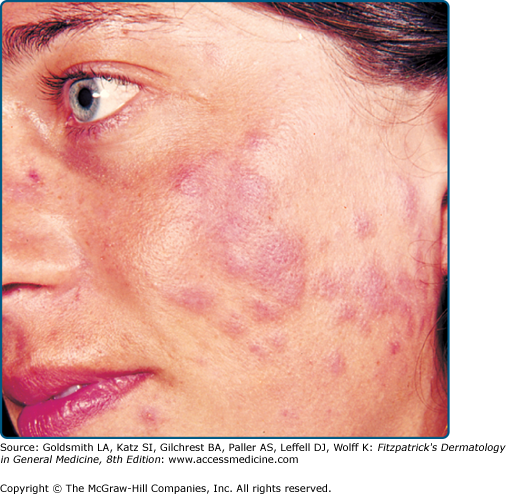

The typical PMLE eruption (Fig. 91-2) occurs each spring or on sunny vacations after the first substantial UVR exposure following a prolonged period with little exposure. It can also occur after recreational sunbed use or, very rarely, after exposure to visible light,18 and it often abates with continuing exposure. It is rare in winter except after extended outdoor recreational activities. Sufficient exposure may also occur through window glass. The threshold required to trigger PMLE varies from patient to patient and is usually from 30 minutes to several hours, although it may occur several days into a vacation. Lesions appear in hours to days following exposure, but usually in not less than 30 minutes. Patients may note itching as the first sign of an impending PMLE eruption. Once UVR exposure ceases, all lesions gradually resolve fully without scarring over one to several days, occasionally taking a week or two. In any given patient, PMLE outbreaks always tend to affect the same exposed sites. The distribution is generally symmetric. Only some of the exposed skin is usually affected, particularly skin that is habitually covered, and large areas may be spared. An apparent extreme example of PMLE is juvenile spring eruption,20 which tends to affect boys in the spring and is characterized by pruritic papules and vesicles on their ear helices, although typical PMLE sometimes coexists. Systemic symptoms in PMLE are rare, but malaise and nausea may occur.

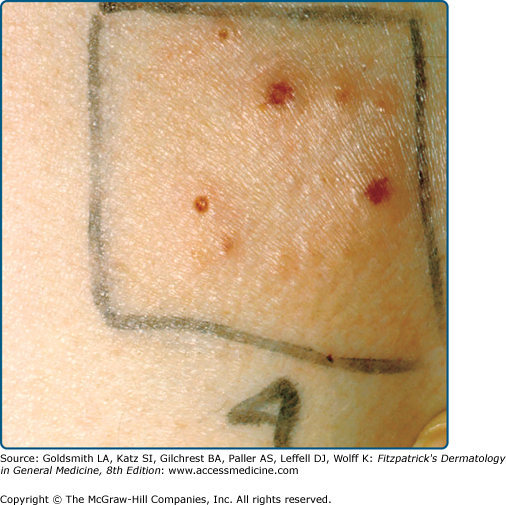

PMLE has many morphologic forms, all probably with similar pathogenesis and prognosis. The term “polymorphous” describes the variability in lesion morphology observed among different patients with the eruption. In fact, the lesions are usually quite monomorphous in an individual patient. Papular, papulovesicular (Fig. 91-3), plaque (Fig. 91-4), vesiculobullous, insect bite-like, and erythema multiforme-like forms have been described, and pruritus alone may even occur, albeit rarely.21 The papular form, characterized by large or small separate or confluent erythematous and edematous papules that generally tend to form clusters, is most common. Papulovesicular and plaque variants occur less frequently, and the other forms are rare. An eczematous form has been claimed but probably refers to mild chronic actinic dermatitis or photoexacerbated seborrheic or atopic dermatitis. Small papular PMLE, generally sparing the face and occurring after several days of continuing exposure, has been designated benign summer light eruption in Europe.22

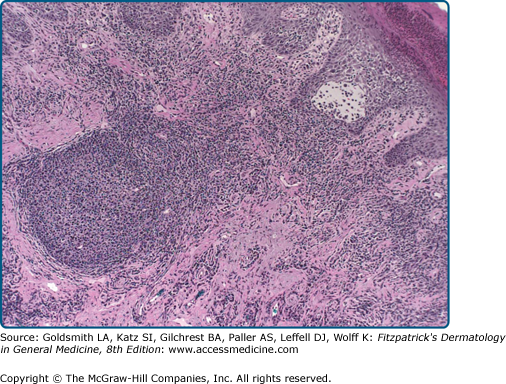

The histologic features of PMLE are characteristic but not pathognomonic,23 and they vary with clinical presentation. There is generally a moderate to dense perivascular infiltrate in the upper and mid dermis in all forms. The infiltrate consists predominantly of T cells, with neutrophils and infrequent eosinophils. Other common features are papillary, dermal and perivascular edema with endothelial cell swelling. Epidermal change, not always present, may include variable spongiosis and occasional dyskeratosis, exocytosis, and basal cell vacuolization.

Assessment for circulating antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and extractable nuclear antibodies (ENA) is advisable to exclude subacute cutaneous or other form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE), and, if there is uncertainty, red blood cell protoporphyrins should be assessed to exclude erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). Approximately 11% of patients with PMLE have been found to have a positive ANA, with the vast majority having insignificant titers of less than 1:160.24 An even smaller fraction (less than 1%) of patients with PMLE have anti-Ro antibodies.24 Clinical correlation is necessary in these patients to exclude the possibility of cutaneous LE.

Cutaneous phototesting with a monochromator confirms photosensitivity in up to half of cases,25 but usually does not differentiate PMLE from other photodermatoses. However, provocation testing with a solar simulator or other broadband source, sometimes repeated over 2 or 3 successive days, may induce the eruption, allowing a subsequent skin biopsy. This is most appropriate when the history and clinical features are not diagnostic.

(See Box 91-1)

A very few patients with PMLE may develop LE, as there is a higher than normal prevalence of prior PMLE in patients with LE.26 However, the presence of autoantibodies does not portend development of LE. Patients with PMLE may also experience significant disease-related psychosocial morbidity. The rate of both anxiety and depression in patients with PMLE are twice that of the general population, and these rates are similar to those observed in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.27

Over 7 years, 57% of 114 patients reported steadily diminishing sun sensitivity, including 11% in whom the condition cleared.28

PMLE may often be avoided by moderating sunlight exposure, wearing protective clothing, and applying broad-spectrum high-protection-factor sunscreens regularly. Sunscreens with UVA and UVB protection may prevent PMLE eruptions in photoprovocable patients,29 but sunscreens without UVA protection are generally ineffective. Prophylactic phototherapy each spring or before sunny vacations tends to prevent attacks.

The first goal in treating PMLE is to prevent it. As noted above, one should advise restricting midday sunlight exposure and employing frequent applications of broad-spectrum, high-protection sunscreens. If this is not fully effective, patients who have outbreaks only infrequently, such as on vacations, usually respond well to short courses of oral steroids that are prescribed and taken with them to use in the event of an eruption.30 If PMLE does develop, approximately 20–30 mg prednisone taken at the first sign of pruritus and then each morning until the eruption clears usually provides relief within several days, and recurrences are then uncommon during the same vacation. This treatment, if well tolerated, may be repeated safely every few months.

More severely affected individuals who experience repeated attacks of PMLE throughout the summer may require prophylactic courses of low-dose photochemotherapy (psoralen and UVA radiation: PUVA) in the spring. This appears to be more effective than broadband UVB radiation, controlling symptoms in up to 90% compared to approximately 60% of cases.31 Narrowband (311-nm) UVB phototherapy, effective in 70%–80% of cases, is now probably the treatment of choice, because of ease of administration.32 Prophylactic PUVA or UVB irradiation may sometimes trigger the eruption, particularly in severely affected patients, in which case a brief course of oral steroid therapy is indicated.

Various other therapies have also been tried but appear largely ineffective. These include hydroxychloroquine,33 which is perhaps occasionally useful; β-carotene,34 which is rarely effective; nicotinamide,35 which is usually ineffective; and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are perhaps of moderate assistance in some patients.36

A small percentage of patients remain who are unsuitable for, unable to tolerate, or not helped by any of these measures. For these patients, when severely affected, oral immunosuppressive therapy, usually intermittent, with azathioprine or cyclosporine can be helpful.37,38

|

Actinic prurigo (AP) occurs throughout much of the world. Native North and South Americans are particularly affected. The disease is estimated to occur in 2% of the Canadian Inuit population.39 In Mexico, AP is seen most commonly in the indigenous and Mestizo populations living at altitudes greater than 1,000 m.40 Less commonly, inhabitants of Europe, United States, Australia, and Japan are reported to develop AP.

AP appears to be UVR-induced in that it is more severe in spring and summer and often demonstrates abnormal skin phototest responses to UVB and/or UVA radiation.41 UVA is implicated more often than UVB.42 The cytokine TNF-α is overexpressed by keratinocytes in lesions of AP, creating a proinflammatory environment.40 Sunlight exposure and solar simulating irradiation may sometimes induce an eruption resembling PMLE in patients with AP, and many patients have close relatives with PMLE.19 A dermal, perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate similar to that of PMLE may be seen in early lesions.

Therefore, AP may be a slowly evolving, excoriated variant of PMLE, and thus also a DTH reaction. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DRB1*0407 (DR4) is found in 60%–70% of patients with AP but in only 4%–8% of normal DR4 positive controls.42 Additionally, HLA DRB1*0401 is found in approximately 20% of affected individuals.42 These immunogenetic features may well be responsible for modulating conventional PMLE into AP. In addition, in some patients, AP appears to transform into PMLE and, in others, PMLE appears to transform into AP,43 all of which suggests a relationship between the two disorders. The cutaneous UVR chromophores responsible for the eruption are not known, but they are likely to be diverse.

AP occurs more commonly in females, with a female to male ratio of about 2:1.42 The eruption has its onset in childhood, usually present by age 10 years.41 A positive family history of either AP or PMLE is present in about a fifth of patients.19 The eruption is often present all year round, but it is commonly worse in summer. Very rarely it is worse in winter or both spring and fall, with immunologic tolerance presumably developing during the summer. Exacerbations tend to begin gradually during sunny weather in general rather than after specific sun exposure, although PMLE-like outbreaks may also occur.

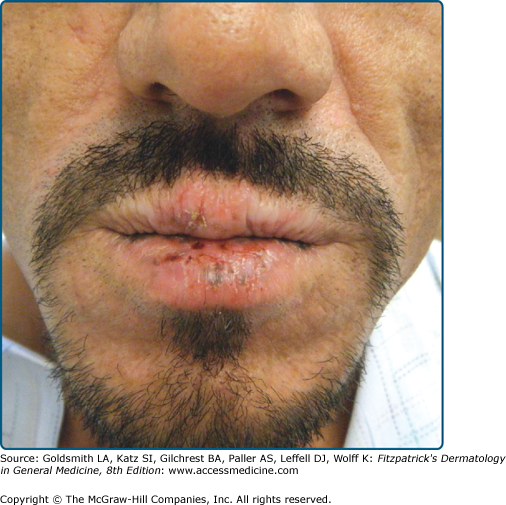

The primary lesion of AP is a pruritic papule or nodule that occurs singly or in clusters (Fig. 91-5). Papules and nodules are often excoriated and crusted, and plaques may assume a lichenified or eczematous appearance. Vesicles are not seen unless superinfection is present.42 Sun-exposed areas are most often affected, particularly the forehead, chin, cheeks, ears, and forearms. There is a gradual fading toward habitually covered skin, and the sacral area and buttocks may be mildly affected. Lower lip cheilitis and conjunctivitis are also possible, particularly in Native Americans44 (Figs. 91-6, and 91-7). Healed facial lesions may leave dyspigmentation and sall pitted or linear scars.

Early papular lesions show changes similar to those of PMLE, namely, mild acanthosis, exocytosis, and spongiosis in the epidermis and a moderate lymphohistiocytic superficial and middermal perivascular infiltrate.23 A dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate and lymphoid follicles may be seen in lesions from the lip.40 In persistent lesions, however, excoriations, more acanthosis, variable lichenification, and a dense mononuclear cell infiltrate produce a nonspecific appearance.

Assessment of ANA and ENA should be undertaken to exclude subacute cutaneous or other forms of cutaneous LE. The finding of HLA type DRB1*0401 (DR4) or DRB1*0407, especially the latter, supports the diagnosis of AP.

Cutaneous phototesting with a monochromator confirms light sensitivity in up to half of cases,41 but, as in PMLE, does not differentiate other photodermatoses. Most patients with positive monochromator testing have reduced minimal erythema doses (MED) in the UVA spectrum or in the combined UVA/UVB spectra.42 Provocation testing with a solar simulator or other broadband sources induces typical lesions of AP in about two-thirds of patients.42

(See Box 91-2)

Mild scarring, especially on the face, and hypopigmentation may result from excoriations associated with AP. Additionally, two cases of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma arising on the face in patients with AP have been reported.45

AP commonly arises in childhood and often improves or resolves in adolescence, although persistence into adult life is possible. Persistent cases may assume features of PMLE in adulthood. More rarely, the disorder arises in adulthood and persists indefinitely.46

Prevention begins by restricting midday sunlight exposure and the compulsive use of broad-spectrum sunscreens.46 In addition, topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be effective in preventing recurrences in patients with previously documented disease. Of course, there is no known way to prevent its initial onset.

In less severe cases of AP, sufficient relief may be achieved by restricting sun exposure and by using broad-spectrum, high-protection-factor sunscreens alone.47 Higher potency topical corticosteroids may be used to relieve the inflammation and pruritus associated with the disease. Phototherapy with narrowband UVB or PUVA may occasionally help,48 perhaps more reliably if the skin is cleared first with oral steroids. Topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus may also help, again if the skin is cleared first. The treatment of choice in more severe or recalcitrant cases is thalidomide, with initial doses of 50–100 mg daily, preferably given intermittently. Responses to thalidomide are evident in most patients within several weeks. The most serious complication associated with thalidomide is teratogenicity, so pregnancy must be rigorously avoided. Other potential adverse effects are typically mild, including drowsiness, headache, constipation, and weight gain. An increased risk of thromboembolism and dose-related peripheral (mostly sensory) neuropathy are other potential adverse effects of thalidomide. In cases where thalidomide is unavailable or otherwise not appropriate, oral immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine or cyclosporine may also be considered.

|

Hydroa vacciniforme (HV) occurs in North America, Europe, Japan, and very likely elsewhere. However, its rarity and lack of universally acknowledged diagnostic criteria may make the diagnosis difficult to establish.

The pathogenesis of HV is not known. No chromophores have been identified, and although UVB minimal erythemal dose responses are normal in most patients, some have increased UVA sensitivity.49 Blood, urine, and stool porphyrin concentrations are normal, as are all other laboratory tests. Nevertheless, its clear relationship to sunlight exposure, its distribution, and its early clinical appearances are all similar to that of PMLE, which suggests a relationship. On the other hand, fully developed HV eruptions are more severe than those found in PMLE, are associated with permanent scarring, and are unresponsive to treatments ordinarily effective in PMLE, apart perhaps from sunscreens and occasionally prophylactic phototherapy. Reports from Asia and Mexico have linked HV to chronic Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection,50,51 although a relationship between EBV and HV in all populations has not been established. Japanese reports indicate that EBV nucleic acids are found in the cutaneous lesions of HV in 85%–95% of patients but not in lesional skin of control patients.51,52 A recent report from France has now provided substantial evidence that EBV infection persists in adult patients with HV and that it plays an important pathogenic role.53

HV commonly develops in early childhood and resolves spontaneously by puberty, although, in some patients, it is lifelong. There is male predominance for severe forms, whereas milder disease is more common in females.49,54 Familial incidence is exceptional. One estimate of the prevalence of HV is 0.34 cases per 100,000 with an approximately equal sex ratio; males had a later onset and longer duration of the disorder than females.54

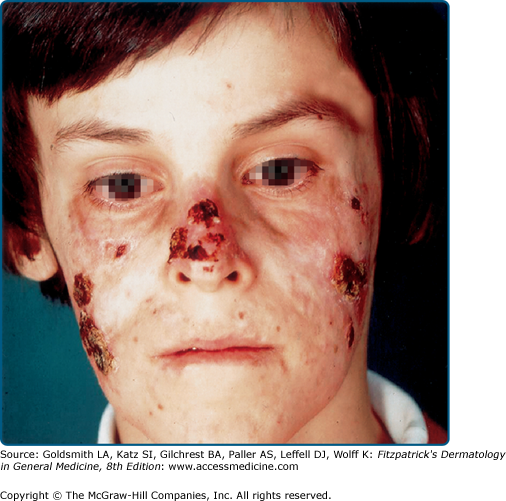

HV eruptions typically occur in summer,41 often with an intense burning or stinging sensation followed by the appearance of individual or confluent papules and then vesicles, all within hours of sunlight exposure (Fig. 91-8). This is followed by umbilication, crusting, and progression to permanent pock scarring within weeks. The eruption affects the cheeks and, to a lesser extent, other areas of the face as well as the backs of the hands and outer aspects of the arms. The distribution tends to be symmetrical.

HV is characterized by initial erythema, sometimes with swelling, followed by symmetrically scattered, usually tender papules within 24 hours; vesiculation, occasionally confluent and hemorrhagic (Fig. 91-9); umbilication; then crusting and detachment of the lesions with permanent, depressed, hypopigmented scars within weeks. These scars are invariably present. Oral ulcers and eye signs also occur rarely.55,56

Early histologic changes include intraepidermal vesicle formation with subsequent focal epidermal keratinocyte necrosis and spongiosis. There is a dermal perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate.23 Older lesions show necrosis, ulceration, and scarring. Vasculitic features have been reported.49

Blood, urine, and stool porphyrin concentrations should be assessed to exclude cutaneous porphyria, and an ANA and ENA to exclude the small possibility of cutaneous LE.

Phototesting may show increased sensitivity to short-wavelength UVA in some patients, but phototesting usually does not discriminate HV from other photodermatoses. Simulated solar irradiation may also induce erythema at reduced doses or occasionally provoke the typical vesiculation of HV (see Fig. 91-7).

Viral studies for herpes infection or other viral disorders should be undertaken if photoexacerbation or photoinduction of these other disorders seems at all possible.

(See Box 91-3).

There are reports of severe HV-like eruptions occurring in patients with chronic EBV infection and other associated disorders such as hypersensitivity to mosquito bites and the hemophagocytic syndrome. HV-like eruptions are distinguished from true HV by the development of lesions in both exposed and sun-protected skin and by the presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and wasting.51,57 The distinction between an HV-like eruption and true HV is important because patients with a severe HV-like eruption may rarely go on to develop potentially fatal hematologic malignancy.56–59 Finally, a recent quality-of-life study indicates that HV causes embarrassment and self-consciousness among children with the disease.60 The negative impact of HV on quality of life exceeds previously reported indices for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.60

Pock scarring is an inevitable sequela of HV. Cases of severe HV-like eruption may progress to lymphoproliferative disease.

HV often resolves in adolescence but may occasionally persist into adult life.

Sun avoidance and sunscreen use, as well as prophylactic phototherapy annually in spring, tend to prevent HV in some patients.

Treatment of HV consists of restricting sunlight exposure and use of high-protection-factor broad-spectrum sunscreens. Occasionally, antimalarials appear to have helped, but their true value has not been established. As with PMLE, prophylactic phototherapy with narrowband UVB or PUVA, particularly the latter, may be helpful but must be administered with care to avoid disease exacerbation.49,53,61 If conservative measures are ineffective, however, as often occurs, topical or intermittent oral steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or even oral immunosuppressive medication may be tried if clinically appropriate, though these agents too are usually ineffective. In patients with chronic EBV infection, antiviral therapy with acyclovir and valacyclovir was reported in a small series of patients to reduce the frequency and severity of eruptions.62

|

![]() (see Table 91-2).

(see Table 91-2).

![]() Persistent light reactivity was first noted in 1933 in a patient who was given intravenous trypaflavine.63 It was not reported again until 1960 when there was an outbreak of persistent photosensitivity that followed photocontact dermatitis to tetrachlorosalicylanilide, an antibacterial agent used at that time in soaps and toiletries.64 This condition was later named persistent light reaction,65 which referred to a severe, persistent photosensitivity of not just exposed but also unexposed skin that developed rarely after photoallergic contact sensitization. The halogenated salicylanilides were implicated as were other substances such as musk ambrette66 and quinoxaline dioxide, and usually in elderly males.67 An initial photocontact dermatitis persisted in rare instances despite complete avoidance of further chemical exposure, and the wavelengths inducing the disorder changed from UVA alone to include UVB radiation or even UVB radiation exclusively. Even visible light was implicated, albeit rarely.

Persistent light reactivity was first noted in 1933 in a patient who was given intravenous trypaflavine.63 It was not reported again until 1960 when there was an outbreak of persistent photosensitivity that followed photocontact dermatitis to tetrachlorosalicylanilide, an antibacterial agent used at that time in soaps and toiletries.64 This condition was later named persistent light reaction,65 which referred to a severe, persistent photosensitivity of not just exposed but also unexposed skin that developed rarely after photoallergic contact sensitization. The halogenated salicylanilides were implicated as were other substances such as musk ambrette66 and quinoxaline dioxide, and usually in elderly males.67 An initial photocontact dermatitis persisted in rare instances despite complete avoidance of further chemical exposure, and the wavelengths inducing the disorder changed from UVA alone to include UVB radiation or even UVB radiation exclusively. Even visible light was implicated, albeit rarely.

|

![]() In 1969, Ive et al68 introduced the term actinic reticuloid to describe a similar but more severe disorder not associated with prior photocontact dermatitis. The condition again affected elderly males primarily, although it was characterized by more infiltrated eczematous plaques, mainly on exposed sites. The histopathologic features in these patients tended to resemble those of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and very abnormal responses to the UVB, UVA, and occasionally visible wavelengths were also seen. Furthermore, although the authors noted a resemblance to persistent light reactivity, results of photopatch testing to all common photoallergens were negative. Similar but purely eczematous variants of the condition, also without overt preceding photoallergy, were then described, with action spectra limited to the UVB range (photosensitive eczema)69 or UVB and UVA ranges (photosensitivity dermatitis).70

In 1969, Ive et al68 introduced the term actinic reticuloid to describe a similar but more severe disorder not associated with prior photocontact dermatitis. The condition again affected elderly males primarily, although it was characterized by more infiltrated eczematous plaques, mainly on exposed sites. The histopathologic features in these patients tended to resemble those of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and very abnormal responses to the UVB, UVA, and occasionally visible wavelengths were also seen. Furthermore, although the authors noted a resemblance to persistent light reactivity, results of photopatch testing to all common photoallergens were negative. Similar but purely eczematous variants of the condition, also without overt preceding photoallergy, were then described, with action spectra limited to the UVB range (photosensitive eczema)69 or UVB and UVA ranges (photosensitivity dermatitis).70

![]() In 1979, Hawk and Magnus71 proposed that actinic reticuloid, photosensitive eczema, and photosensitivity dermatitis were part of the same syndrome, which they termed chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD), following reports that photosensitive eczema could progress to actinic reticuloid and vice versa.72 This analysis was further supported by the occasional association of the clinicopathologic features of actinic reticuloid with just UVB photosensitivity,71 a final theoretical variant of CAD not previously described. Furthermore, in view of the marked clinical, histologic, and photobiologic similarities between persistent light reaction and CAD, it was later decided that these two entities were also the same.

In 1979, Hawk and Magnus71 proposed that actinic reticuloid, photosensitive eczema, and photosensitivity dermatitis were part of the same syndrome, which they termed chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD), following reports that photosensitive eczema could progress to actinic reticuloid and vice versa.72 This analysis was further supported by the occasional association of the clinicopathologic features of actinic reticuloid with just UVB photosensitivity,71 a final theoretical variant of CAD not previously described. Furthermore, in view of the marked clinical, histologic, and photobiologic similarities between persistent light reaction and CAD, it was later decided that these two entities were also the same.

Chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD) has regularly been diagnosed in Europe, North America, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and India. The disorder therefore appears to have worldwide distribution, affecting all skin types, although it is perhaps more common in temperate regions.

Studies of the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical features of CAD all show it to resemble the DTH reaction of allergic contact dermatitis,73–75 even in its severe pseudolymphomatous form (formerly called actinic reticuloid), in which the clinical and histologic features duplicate those seen in long-standing allergic contact dermatitis.76 It is therefore highly probable that CAD is an allergic reaction. In addition to hypersensitivity to cutaneous photoantigens, patients with CAD often have concomitant allergic contact dermatitis to airborne or other ubiquitous allergens, including plant compounds, fragrances, and medicaments.77 Commonly implicated allergens include sesquiterpene lactone from plants of the Compositae family and sunscreens. A recent study indicates that sesquiterpene lactone remains the most common allergen in patients with CAD, with positive and clinically relevant photopatch testing to this allergen documented in approximately 20% of patients.78 In addition, cc has emerged as an increasingly common antigen in CAD78

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree