Abdominoplasty and Belt Lipectomy

Al S. Aly

Emil J. Kohan

INTRODUCTION

Body contouring of the lower trunk region is an integral part of the plastic surgeon’s armamentarium. The lower trunk is a circumferential structure that begins at the inferior border of the breasts and ends at the pelvic rim. Although this is a convenient unit, it is difficult to separate from surrounding structures such as the thighs and the thorax. Deformities in the lower truncal region are variable in nature and require different approaches for their treatment. Recent advances in bariatric surgery have resulted in a large population of weight loss patients, which has led to an emphasis on the evaluation and treatment of lower truncal contour deformities. This chapter will focus on excisional procedures, with or without liposuction, in the treatment of lower truncal deformities. Problems that can be ameliorated by liposuction techniques alone are covered in Chapter 65.

PATIENT PRESENTATION

Patients with lower truncal complaints demonstrate a variety of deformities on a continuum from minimal excess fat to circumferential fat and skin excess accompanied by abdominal laxity of the fascia1 (Table 66.1).

Weight is the first important factor that affects the presentation of patients with lower truncal deformities. Because absolute weights can be misleading, body mass index (BMI), which relates weight to height, is the most commonly used parameter. It is calculated in the following manner:

Body mass index = weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2

Body mass index = weight in pounds/(height in inches)2 × 703

Patients who present for lower truncal contouring span the range of BMI from normal to obese.

The upper limit of normal BMI is 25; 26 to 30 is considered overweight; and 30 and above is considered obese. A variety of surgical approaches are required to treat patients in different BMI ranges.

A second factor that affects the presentation of patients is the fat deposition pattern, which is genetically controlled. Women typically deposit fat in the infraumbilical abdomen, lateral thighs, hips, and medial thighs. Men tend to deposit fat in the flanks, the infraumbilical abdomen, and intra-abdominally.2 Although these patterns are common, dramatically different patterns of fat deposition are often present even within the same gender.

The quality of the skin-fat envelope is a third factor to evaluate. Some women who have had one or more pregnancies may present with abdominal skin laxity and stretch marks. The skin in those patients is stretched beyond its ability to rebound back to its original elasticity. A similar process occurs with massive weight gain and subsequent weight loss in which the skin is overexpanded, leading to a skin-fat envelope that is loose and inelastic.

TABLE 66.1 FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE PRESENTATION OF THE PATIENT REQUESTING LOWER TRUNCAL CONTOURING | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

HISTORY OF BODY CONTOURING

Body contouring procedures early in the twentieth century consisted of dermatolipectomies of hanging abdominal panniculi. In these procedures, excess skin and underlying fat were removed to rid the patient of hanging tissues with minimal attention to aesthetic principles. In the second half of the century, advances in abdominoplasty techniques led to improved scar placement, abdominal wall plication, and umbilical transposition. In the 1980s, liposuction was introduced, and it became a tremendous tool in the armamentarium of the plastic surgeon for affecting body contour, replacing a number of excisional procedures. Currently, plastic surgeons routinely use both excisional and liposuction techniques, alone and in combination, to improve abdominal contour.

RELEVANT ANATOMY

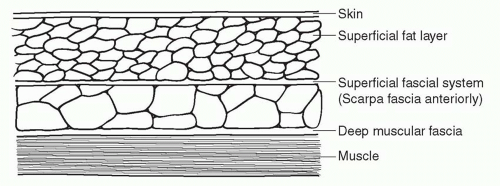

Fat in the lower trunk is organized into superficial and deep layers separated by the superficial fascial system, which pervades the entire body. Anteriorly the superficial fascial system is referred to as Scarpa’s fascia (Figure 66.1).

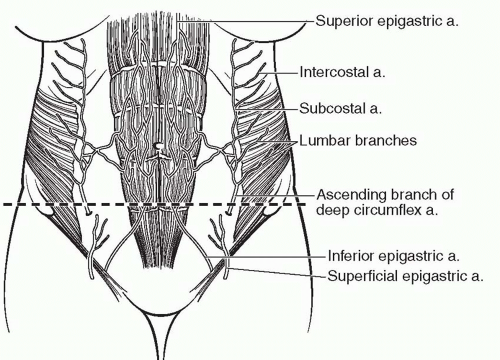

The blood supply of the abdominal skin and fat is important to understand. The skin overlying the rectus muscles is primarily supplied by arteries that originate from the superior and inferior epigastric vessels that run within the rectus muscles. Branches from these vessels perforate the overlying rectus fascia and traverse through the two layers of abdominal fat, finally reaching the skin. This direct blood supply of abdominal skin is interrupted during the elevation of the abdominal flap in a traditional abdominoplasty. A secondary blood supply is derived from lateral intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar vessels that course anteriorly in the fat superficial to Scarpa’s fascia (Figure 66.2). These vessels are the only remaining blood supply of central abdominal skin after traditional flap elevation. Interruption of these vessels by scars, such as cholecystectomy, or chevron scars, can lead to necrosis of tissues inferomedial to the scar. The superficial epigastric vessels supply blood to the skin of the lower abdomen but are also divided during abdominoplasty procedures.

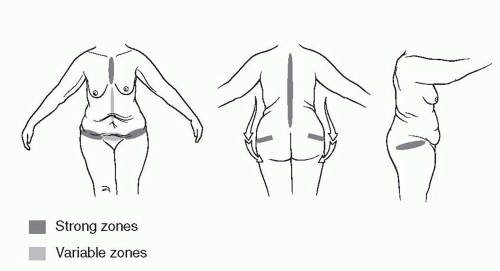

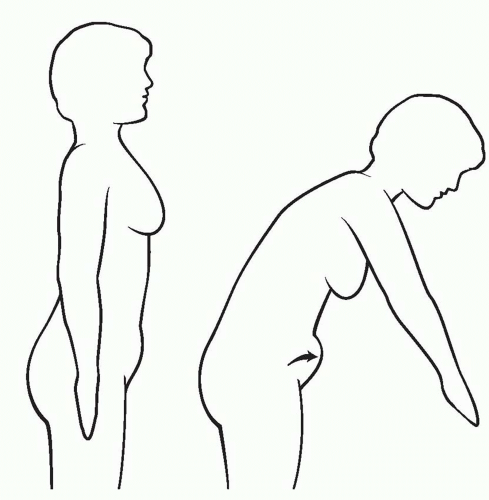

The lower trunk has fascial attachments between the skin and the underlying muscle fascia that act as anchoring points or zones of adherence3 (Figure 66.3). These zones of adherence restrict the overlying skin from moving during the processes of aging and/or weight fluctuations. Posteriorly, the midline has a zone of adherence that overlies the spine. The anterior midline of the abdomen has a less well-defined zone of adherence. Three horizontal zones of adherence are located in the inferior aspects of the lower trunk; one is located at the inguinal region bilaterally and extends toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Another is located just above the mons pubis and is variable in its adherence properties. The third is located bilaterally between the hip and lateral thigh fat

deposits. Truncal tissues become lax due to aging, pregnancy, and/or massive weight loss. They descend the greatest distance laterally, caused by a combination of tissue laxity and central tethering of the midline zones of adherence. As tissues descend around the pelvis they also migrate centrally (see Figure 66.3).

deposits. Truncal tissues become lax due to aging, pregnancy, and/or massive weight loss. They descend the greatest distance laterally, caused by a combination of tissue laxity and central tethering of the midline zones of adherence. As tissues descend around the pelvis they also migrate centrally (see Figure 66.3).

The inguinal and mons pubis zones of adherence are responsible for holding the final position of abdominoplasty scars in the lower truncal region. Without their effect, the scars would migrate cephalad, possibly above natural underwear lines.

PATIENT SELECTION

Patients who have minimal to moderate subcutaneous fat excess and no abdominal wall laxity are good candidates for liposuction alone. Patients who present with abdominal wall laxity and minimal abdominal skin excess limited to the infraumbilical region are good candidates for mini-abdominoplasty. Patients who present with abdominal wall laxity of both the infra- and supraumbilical regions and generalized skin excess limited to the anterior aspects of the lower trunk are good candidates for a full abdominoplasty. As the deformities increase in magnitude and involve the lateral and posterior aspects of the lower trunk, circumferential truncal liposuction and/or dermatolipectomies become necessary. The indications, goals, and a general description of each procedure are given below.

Lower truncal body contouring procedures are often long and extensive in nature. Medical problems such as heart disease, diabetes, and lung disease must be under control before surgery is contemplated. Cigarette smoking also has a deleterious effect on blood supply and, when combined with the already compromised vascular supply of the abdominal skin, can lead to significant tissue necrosis. Many plastic surgeons avoid performing abdominoplasty on active smokers.

MINI-ABDOMINOPLASTY

Women who present with abdominal wall laxity restricted to the infraumbilical region that is associated with minimal infraumbilical skin and fat excess are candidates for a miniabdominoplasty. Physical examination of the abdomen in the supine position will demonstrate infraumbilical rectus diastasis, which can be confirmed by the “diver’s test” (Figure 66.4).

FIGURE 66.4. The classic “diver’s test” demonstrates how a bend at the waist will reveal the true extent of abdominal wall laxity. |

These patients are usually young women who have had one or two pregnancies, have good skin elasticity, and are not overweight. They may or may not have localized fat deposits in other areas of the trunk and lower extremity such as the hips and lateral thighs. The goal of surgery in this patient population is to eliminate the infraumbilical abdominal wall laxity and the minimal skin and fat excess.

Technique (Mini-Abdominoplasty)

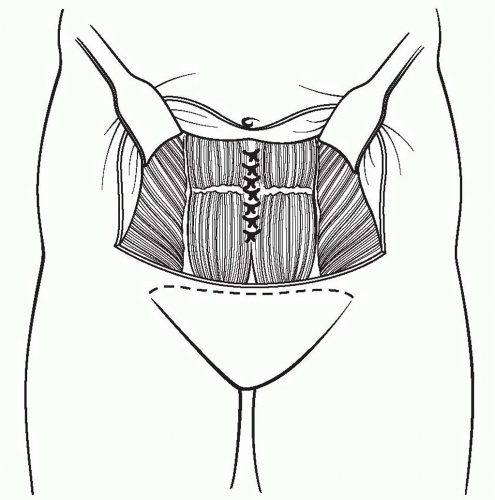

An incision is marked in the patient’s natural suprapubic crease and angled toward the ASIS. Often the incision can be limited to the width of the pubic hair or just beyond its lateral edges. Intraoperatively, the proposed incision is made and the dissection extended to the muscle fascia. An abdominal flap is elevated superiorly to the level of the umbilicus. The infraumbilical rectus muscle diastasis is identified, and rectus fascia plication is performed. Some surgeons prefer a single layer, whereas others favor a two-layer plication (Figure 66.5). The abdominal flap is advanced inferiorly and tailored to remove the excess skin and underlying fat. This advancement will usually pull the umbilicus down 1 to 3 cm.

The closure of this incision, as in all subsequent incisions discussed in this chapter, is performed in multiple layers, with the most important layer being the reapproximation of the superficial fascial system, or Scarpa’s fascia.4 Permanent or long-lasting sutures are used in this layer in an attempt to limit widening of the scar in the long run. The authors prefer to use interrupted monofilament absorbable sutures in the subcuticular layer to perfectly approximate the skin with an overlying layer of medical-grade skin glue. Drains are inserted and a compression garment is used in the postoperative period by most surgeons.

A variation of this technique can be used in patients who have minimal lower abdominal skin excess, no upper abdominal skin excess, and both infra- and supraumbilical rectus diastasis. To allow access to the supraumbilical rectus diastasis, the base of the umbilicus can be amputated. The abdominal flap is then elevated on either side of the midline in the supraumbilical region, and a supraumbilical rectus plication and an infraumbilical plication are performed. The umbilical stalk is then resutured to the plication at the appropriate level, and the lower aspect of the abdominal flap is tailored appropriately. It is also possible to use a minimal-incision approach to the supraumbilical plication by making an incision in the superior aspect of the umbilicus and using an endoscope to perform a dissection superior to the umbilicus that is wide enough to allow for the desired supraumbilical plication. In any of the mini-abdominoplasty techniques discussed, liposuction can be used to decrease the thickness of any part of the abdominal flap that has not been elevated.

One of the most difficult aspects of mini-abdominoplasty is avoiding dog-ears because of the short incision.

ABDOMINOPLASTY

Generally, abdominoplasty is indicated in patients whose laxity involves the supra- and infraumbilical regions, limited to the anterior aspects of the lower trunk. The goals of abdominoplasty depend on the presenting deformities. They include creating a flat abdominal contour, eliminating abdominal wall laxity, enhancing waist definition in some patients, and eradicating mons pubis ptosis if present.

Stretch marks are common and may be limited to the infraumbilical region or may include both the infra- and supraumbilical skin. Rectus diastasis of the entire vertical extent of the abdomen is present in these patients, with the infraumbilical diastasis usually more extensive because of the position of the uterus during pregnancy. Preoperatively abdominal wall laxity can again be detected by the “diver’s test” and physical examination. Massive-weight-loss patients who reach a near-normal BMI may also present with lower truncal excess limited to the anterior abdomen. However, most often they present with circumferential deformities that require more extensive circumferential excisions.

Patients who present with excess intra-abdominal fat that would prevent flattening of the abdominal wall by plication are not good candidates for abdominoplasty. The outer skin/fat envelope of the belly always conforms to the shape of an inner balloon whose anterior wall is made up of the abdominal muscle wall. If that wall is rendered convex in profile by virtue of overly abundant intra-abdominal contents, then the final profile of the belly will also be convex. Because abdominal contour flattening is one of the major goals of surgery, these patients are better served by weight loss prior to contemplating abdominoplasty-type procedures.

By the nature of an abdominoplasty, where an ellipse of tissue is removed from the lower abdomen, dog-ears can be created at the edges of the ellipse, especially in patients who already have lateral excess. Patients who present with deformities that extend beyond the anterior aspects of the lower trunk may require 1) extending the abdominoplasty excision laterally, 2) liposuction of the lateral and posterior trunk, and/ or 3) circumferential dermatolipectomy to attain the best possible contour.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree