n, lichen planus (LP) is defined as ‘an eruption of flat-topped, shiny, violaceous papules’ [1]. In the field of dermatology, the term lichenoid is often used as a descriptor of flat-topped papules and thin plaques, either discrete or grouped. The term is also used in histopathology to define a pattern of inflammation similar to that of lichen planus, ‘a band-like dermal lymphocytic infiltrate in close approximation to the epidermis’ [2].

History.

First coined by Erasmus Wilson in 1869 and probably referring to the condition described earlier by Hebra as ‘leichen ruber’, the classic description of lichen planus has not changed over time [3]. The characteristic fine white scale resembling lace was described by Wickham in 1895 as peculiar dots and striae and is now commonly known as ‘Wickham’s striae’ [3,4]. Darier, another father of dermatology, added to the pathological description of this condition by correlating the finding of Wickham’s striae to an increase in the thickness of the granular cell layer [5].

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

Many theories regarding the aetiology of LP have been proposed but an exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated. An autoimmune mechanism was first proposed by Black in 1977 based on his observations of the following:

- LP may appear clinically and histologically similar to lupus erythematosus

- LP can occur in association with other autoimmune diseases such as ulcerative colitis, myasthenia gravis, alopecia areata and vitiligo

- immunoglobulin staining of colloid bodies, the basement membrane zone and papillary dermis is similar to other autoimmune disorders

- certain HLA phenotypes may predispose individuals to LP [6].

Anecdotal cases of LP eruptions co-existing with thymoma, alopecia areata, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, vitiligo, discoid lupus erythematosus, localized scleroderma, Hashimoto thyroiditis and Sjögren syndrome have been reported [7–14].

Box 85.1 Lichen planus – reported extracutaneous associations

- Alopecia areata

- Hashimoto thyroiditis

- Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

- Localized scleroderma

- Lupus erythematosus

- Myasthenia gravis

- Sjögren syndrome

- Ulcerative colitis

- Vitiligo

Specific human leucocyte antigen (HLA) types have been associated with LP and may represent an immunogenetic component in the pathogenesis of this disease. Initial investigations described patients with LP and HLA-A3 and HLA-A5 [15,16]. Later, an increased frequency of HLA-DR1 was described in a cohort of patients with localized, generalized and drug-induced LP from the Mayo Clinic [17]; this finding was supported by another similar study in Italian patients [18]. Population-specific HLA types have also been described in LP. Patients of Arabic descent with LP were reported to have an increased frequency of HLA-DR1 as well as HLA-DR10 [19]. An analysis of Israeli Jewish patients with oral erosive LP showed a significant association with HLA-DR2 [20]. Other population-specific HLA types in LP patients have included a predominance of HLA-DR3 in Swedish patients with oral erosive LP, HLA-DR9 in Japanese and Chinese patients with oral LP, and HLA-DRB1 in patients of Mexican descent with the majority having classic LP [21–24]. Overall, HLA-DR1 seems to be frequently associated with cutaneous LP regardless of ethnicity [24].

Box 85.2 HLA types associated with lichen planus

- A3

- A5

- DR1 (increased representation regardless of ethnicity)

- DR2 (Israeli Jewish patients)

- DR3 (Swedish patients with oral erosive LP)

- DR9 (Japanese and Chinese patients with oral LP)

- DR10 (Arabic patients)

- DRB1 (Mexican patients with classic LP)

There is significant and growing evidence that LP is T-cell mediated. Past studies attempting to characterize the T-cell infiltrate have led to conflicting data. Some reports have described a predominantly CD4+ T helper cell infiltrate and others a CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell infiltrate [25–29]. These inconsistent results may possibly be due to varying immunohistochemical and molecular techniques and small sample sizes. Several authors report the predominance of CD8+ T-cells at the dermal–epidermal junction and in close proximity to degenerating keratinocytes and CD4+ T-cells in the deeper dermis. These CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrates have been described alongside an increased number of activated macrophages or Langerhans cells (LC) in the dermis and epidermis of active cutaneous lesions and an enhanced major histocompatibility complex class I antigen expression [30,31].

Evidence for the role of chronic cell-mediated cytotoxicity in LP has also been established. In a murine model, autoreactive CD4+ T-cells injected into the footpads of syngeneic mice were able to respond to self MHC class II antigens on local macrophages and Langerhans cells and caused basement membrane damage similar to that seen in humans with LP [25]. Thus, in this murine model, T-cells were able to induce epidermal damage without any alteration in the antigenicity of the epidermis. However, the authors postulate that during the unaltered cutaneous process in LP, exogenous agents such as viruses may alter the antigenicity of epidermal keratinocytes that could trigger activation of T-cells. Many CD8+ T-cells isolated from LP lesional skin have been shown to have cytotoxic activity against lesional and normal kertinocytes as well [32]. Using routine histology, electron microscopy, and by demonstration of apoptotic DNA fragments, evidence exists to support the hypothesis that epidermal damage in LP by T-cells occurs through the process of apoptosis [32–36]. In addition, cytokine expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α and more recently, type 1 IFN produced by plasmacytoid dendritic cells has been found in increased levels in lesional skin [36,37]. Gene expression profiling supports the important role of interferon in LP, demonstrating that specific type I and type II interferon-inducible genes and genes reflecting IFN-associated inflammation were upregulated [38,39]. These cytokines probably play an important role in the chronicity of LP.

Identification of the trigger in those patients susceptible to lichenoid disorders such as LP will help to further understanding of the pathogenesis of LP. In support of a host-specific immunologically mediated process in LP, Gilhar et al. reported the complete disappearance of histological abnormalities of LP when lesional skin from patients with LP was grafted onto the skin of nude mice [40]. Several factors have been implicated in the development of LP including certain medications, contact sensitivity to metals such as amalgam (mercury), copper, palladium, beryllium and gold, and infections such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) [41].

The association of LP and liver disease has been a much-debated issue. LP has been described in patients with chronic active hepatitis (CAH) of unknown cause, HCV, HBV and a small number of cases of patients with primary billiary cirrhosis probably related to concomitant treatment with penicillamine [42–49]. Supporters of this association link a common autoimmune mechanism between CAH and LP, given that CAH may be associated with other immunologically based disorders (such as ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome and Hashimoto thyroiditis) and that similar histological and immunological mechanisms exist between the two conditions [43].

The overall prevalence of LP in patients with liver disease has differed in various studies and ranges from 0% to 44% [50]. In a systematic review of controlled studies analysing the prevalence of HCV infection in those patients with LP, 19 (statistically significant) studies were found which showed a higher proportion of HCV-positive subjects in those patients with LP as compared to control populations [50]. Specifically, geographic regionswith a high prevalence of hepatitis infection in the overall population, such as southern Europe, have reported an increased number of cases of LP in those serologically positive patients. However, further studies from countries with a high prevalence of HCV have also shown no significant associations with LP, suggesting that high prevalence of HCV virus in these populations does not by itself explain the link between the diseases [51–55]. Reports of HCV-positive patients receiving treatment with IFN-α have noted a resolution of existing LP lesions, no change in existing LP lesions, as well as the onset of new LP lesions during therapy [57–62]. In addition, the presence of HCV antibodies is not sufficient to determine that HCV is responsible for the development of mucocutaneous lesions [49].

Given these mixed results, the role of chronic liver disease and its relationship to LP still remains unclear. However, LP has been added to the list of dermatological diseases possibly associated with HCV-induced CAH and the onset of cutaneous disease may enable practitioners to screen and diagnose asymptomatic individuals with CAH.

Lichen planus has also been associated with hepatitis B vaccine in children and adults [63–65]. Approximately 20 case reports of LP in children following HBV vaccine have been reported including nail involvement in a few cases [63,64,66].

Pathology.

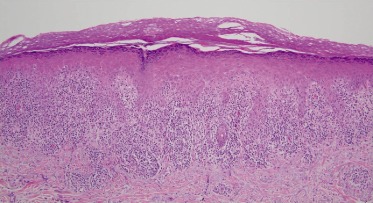

Classic lichen planus possesses characteristic microscopic features that make the histopathological diagnosis relatively straightforward. Typically, a biopsy of LP will reveal orthohyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis with ‘saw-toothing’ of the rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal layer and a dense, band-like lymphocytic infiltrate abutting the epidermis with pigmentary incontinence (Fig. 85.1). Clefts may develop at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ) with an artifactual separation or so-called ‘Max-Joseph spaces’ [67]. Although these clefts are typically small, large clefts may present clinically with bullous lesions as seen in bullous lichen planus. Another classic histological finding in LP is the so-called ‘Civatte bodies’ or colloid bodies, which are eosinophilic globular deposits of degenerated keratinocytes. When LP is present on mucocutaneous sites, hypergranulosis and hyperkeratosis may be absent and parakeratosis rather than orthokeratosis is likely [68]. Lichenoid drug eruptions (LDE) can be difficult to discern from LP due to similar histological features. The presence of eosinophils, neutrophils, parakeratosis and both a deep and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate may favour LDE [69].

Specific features of follicular involvement in lichen planopilaris (LPP) include a reduced hair density and reduction or absence of vellus hairs, arrector pili muscles and sebaceous glands [70]. Significant epidermal changes are usually not noted with LPP and a dense, band-like perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate at the level of the infundibulum and isthmus is common. Dilation of the infundibulum and a perifollicular collar of hypergranulosis in the epidermis around the follicular opening can be seen. Stromal changes in LPP can include hyalinization of the dermis, follicular fibrous tracts and perifollicular scarring that can result in permanent scarring alopecia [70].

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies in LP have shown deposits of multiple immunoglobulins, fibrin and cytoid bodies in lesional skin. Most commonly, fibrin at the DEJ and IgM of the cytoid bodies have been reported [71,72]; IgG, IgA, C3 and fibrin have also been shown depositing on cytoid bodies. In LPP, DIF may reveal deposition of IgM and/or IgA, IgG and uncommonly C3 at the infundibulum and isthmus level [73]. Fibrinogen deposition in a shaggy pattern may surround affected follicles. Indirect immunofluorescence using patient serum and lesional skin of patients with cutaneous LP has demonstrated a specific ‘lichen planus-specific antigen’ in the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum that may be helpful when the diagnosis is in question [74].

Clinical Features

Incidence

While lichen planus more commonly presents in middle-aged adults, childhood presentations are well described [75–84]. The youngest patient described with LP was a female infant believed to have an initial eruption of LP at the age of 3 weeks [85]. Gender distribution continues to be a matter of debate in the literature but most will accept that LP affects both sexes equally (including children and adults) [86]. Although LP has a worldwide distribution, there seems to be an increased incidence of childhood- and young adult-onset LP in the tropics and subtropics [76–81,87,88]. In support of this association, children of tropical and subtropical extraction living in temperate climates have been over-represented in studies of childhood LP as compared to rates expected in the population [75,84,89].

The overall incidence of childhood LP is difficult to discern as estimates vary based on geographic region and may be based on total cases of LP seen over a certain time period or overall paediatric dermatological cases seen. For example, in a series of 13 children with LP in Nigeria, these cases accounted for less than 0.1% of the overall LP cases seen in that practice [83]. In a report from Mexico, 24 (10%) out of the 235 patients with LP were children [81]. Case series have been described in India as well [78,79]. In a series of 87 cases by Handa & Sahoo, several atypical variants of LP were seen including cases of nail involvement, actinic and eruptive LP, lichen planopilaris and oral LP, as well as noted involvement of the palms, soles and upper eyelids [80]. A case series of 23 children with LP in Kuwait noted scalp involvement in two patients, nine patients with mucosal involvement, and one familial case [79]. These 23 cases of LP constituted 0.13% of all cases diagnosed in the authors’ paediatric dermatology clinic. Kumar et al. reported 222 patients with LP (0.6% overall) who attended their hospital during their study period, of which 25 (11.2%) were children below age 14 years [77]. Other authors have reported that less than 1% of cases [90], 1.61% [76] and 3.9% [75] of LP cases have involved children.

Familial or inherited LP may not be as rare as once thought and may occur in up to 10% of cases (range 2–10.7%) [90–93]. Familial LP has also been described in monozygotic twins [94–98]. Cases will often demonstrate an earlier age of onset of disease, more frequent mucosal and generalized involvement, a higher relapse rate and a more chronic course [92,99,100]. One study suggested an increased incidence of HLA-B7 in familial cases of LP as compared to sporadic cases, but other studies have failed to support this finding [101].

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Classic lichen planus appears as purple to violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules with a fine network of lace-like scale referred to as ‘Wickham’s striae’ [4] (Fig. 85.2). The lesions may range from pinpoint papules, a few millimetres in size, to larger, thin plaques up to 1.5 cm and may occur in groups, in isolation or in a generalized pattern (Fig. 85.3). The papules of lichen planus often demonstrate the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear array after trauma such as scratching (Fig. 85.4). The typical locations for cutaneous LP in both adults and children include the wrists, ankles, lower extremities, lower back, and the sides of the neck and genitalia, often in a bilateral symmetrical distribution. Inverse LP (inframammary, axillary and inguinal areas) as well as eyelid and acral involvement are more unusual. Annular plaques and ‘zosteriform’, ‘linear’ and ‘blaschkoid’ variants have been described in the literature [102–104]. Scalp, nail and oral sites of LP are less common and may present with or without other cutaneous findings.

Childhood-onset LP is often similar in presentation to classic LP with lesions typically affecting the lower limbs. Hypertrophic, linear and eruptive variants have been described. Mucosal, nail and scalp involvement can also be seen in children and adolescents. Some authors have reported that atypical cutaneous forms of LP (including atypical locations) may be more common in childhood. Increased nail and follicular involvement and linear forms are seen [75,80,83,102]. However, others have considered childhood-onset LP to be quite similar to the adult form of the disease [76,79].

Approximately two-thirds of affected individuals with cutaneous LP complain of pruritus. This is especially common in those with hypertrophic and generalized disease [91]. LP may leave significant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that can be quite distressing to both patients and their families (Fig. 85.5). Atrophy of involved skin may also occur.

The natural course of disease in children and adults varies. In adults, lesions may persistent from a few months to even years and may be marked by acute flares or exacerbations. Approximately 65–90% of patients will have no disease activity after 1 year [91,105]. In a thorough evaluation of variations in presentation and the course of LP, one study concluded that patients with cutaneous lesions were more likely to have a shorter course of disease as compared to those with solely mucous membrane involvement [91]. Recurrence of disease tended to occur in a small percentage of patients, especially in those with generalized cutaneous involvement [91]. The course of LP in children is similar to the adult course with the majority of disease resolving within 1 year.

Lichen planus of the nails and follicular units represents unique and uncommon presentations. LP of the nails has been described in children in either single case reports or as a minority in small case series [75–77,80,81,83,106,107]. LP limited to the nails has also been reported in children [108–111]. Three types of nail involvement in LP have been described by Tosti et al.: typical nail LP, 20-nail dystrophy (or trachyonychia) and idiopathic atrophy of the nails [112]. In both adults and children, typical nail findings of LP may include longitudinal striations, ridging and pterygium formation and nail plate thinning. Non-specific changes such as pitting, yellow discoloration, onycholysis and shedding of the nails can also be seen [113]. Trachyonychia (rough, lustreless and brittle nails) can also be a sign of LP and has been described as the sole manifestation of disease in some children [108,114] (Fig. 85.6). This subtype is also more commonly seen in children as compared to adults [112,115].

Trachyonychia can affect one, a subset or all of the nails (as in 20-nail dystrophy). It is often an idiopathic disease that improves with time, but may also represent nail involvement of another skin disorder such as LP, psoriasis, alopecia areata or atopic dermatitis. Without other cutaneous or mucosal signs of LP, it may be difficult to make the diagnosis of this type of nail LP without a biopsy for histological evaluation [107,108,116]. However, this type of nail involvement tends to improve after many years. LP of the nails in children can also be severe with pterygium formation, scarring and shedding of the nail plate [77,80,83,111].

Follicular involvement of LP, or lichen planopilaris (LPP), is rare in childhood [76,79,117,118]. In a report of 30 cases of LPP by Chieregato et al., only two patients were under 18 years of age and both had involvement of the vertex scalp with no other cutaneous involvement [118]. When follicular involvement does occur, it can be localized and patchy or a more diffuse process, most commonly involving the vertex and parietal areas of the scalp. Clinically, perifollicular scaling, hyperkeratotic papules, erythema and loss of follicular orifices may be seen; a pull test in which multiple hairs come out with gentle traction may be positive in active areas. Significant follicular involvement leads to cicatricial alopecia and in some cases a ‘pseudo-pelade of Brocq’ or the so-called appearance of ‘white footprints in the snow’ [117,119]. A clinicopathological study of scarring alopecia in 10 patients involved two paediatric patients: a 2-year-old girl with a pseudo-pelade appearance with an LP-like histology and a 6-year old boy with follicular plugging and erythema of the scalp consistent with LPP [117]. LPP can cause significant scalp pruritus, burning and dysaethesias as well as hair loss. Patients may experience significant emotional and psychological distress due to the permanent scarring nature of LPP.

Oral LP occurs most commonly on the buccal mucosa with fine, white, reticulated papules or plaques, but may involve other locations including the tongue and mucosal lip [120,121]. Specific reports of oral LP in children are few [122–126]. Cases of oral LP in children occurred in anywhere from 4% to 40% of children in case series of childhood LP [76,77–79,80,83]. In these cases reticular patches or white plaques on the buccal or gingival mucosa and violaceous papules or plaques on the lips were most commonly described. A review of the literature performed by Woo et al. yielded 42 cases of juvenile oral lichen planus (20 years of age or under) [125]. They concluded that juvenile oral LP occurs most often in children aged 11–15 years with the buccal mucosa or tongue most affected. Oral LP can also become ulcerated or eroded, although this variant is quite rare in children [81,123,124,127,128]. Mucous membrane lesions tend to cause little discomfort except in the erosive oral LP variant which is often described as painful with a burning sensation. Extensive cases may interfere with eating and cause weight loss. In adults, squamous cell carcinoma has been known to develop in chronic LP of the mucosa and therefore periodic oral exams and histological evaluations are necessary when concerning changes occur.

Clinical Variants

Hypertrophic Lichen Planus.

The hypertrophic variant of LP consists of thick, verrucous and hyperkeratotic plaques and papules occurring primarily on the shins and the dorsal aspects of the feet. Lesions may be covered in a fine scale and tend to be symmetrically distributed. On the surrounding skin, small flat-topped polygonal papules may be seen. The eruption is often terribly pruritic and chronic. This variant has been described as more frequent in children [76–80,83]. In adults, squamous cell has been reported to develop within long-standing lesions, and rarely keratoacanthomas [129–135].

Actinic Lichen Planus.

Historically, actinic LP has also been known as LP subtropicus, LP tropicus, LP atrophicus annularis, LP in subtropical countries, LP actinicus, lichenoid melanodermatitis and summertime actinic lichenoid eruption [136–142]. The majority of patients with actinic LP have been reported from the Middle East, although the original cases were reported from northern and southern Italy [136,137,139,143,144]. Subsequent cases have originated from Europe, the United States, India and Africa [137,138,141,142,146,147].

Actinic LP is a distinct variant of LP occurring on sun-exposed skin of the face, especially the lateral forehead. The dorsum of the hands, forearms, lower lip, cheeks and neck may also be affected. The scalp and nails are rarely involved. Occasionally patients will have skin lesions on non-exposed areas such as the trunk, oral mucosa and genitalia. Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation, not UVA, has been shown to induce these lesions [148]. In addition to solar radiation, El Zawahry noted that heat was capable of triggering lesions when a few of his female patients had recurrences after exposure to a hot oven [137]. Well-developed lesions of actinic LP are classically described as annular and can be accompanied by the papules and plaques of classic LP. Frequently, lesions first appear as pigmented brown-blue patches and subsequently develop an elevated hypopigmented border with a central area that appears atrophic or depressed and hyperpigmented. Actinic LP may also mimic melasma [149,150].

The eruption of actinic LP may last many months to several years, unlike classic LP. Although symptoms are usually minimal, pruritus and a burning sensation may occur and symptoms may be intensified by further exposure to sunlight. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be marked and distressing to patients. Actinic LP occurs in younger age groups including children and young adults in the second and third decades of life [77–82,136,149,151]; women may be slightly more affected than men [136]. The incidence is highest during times of maximum sun exposure such as spring and summer months and tends to improve during the winter months.

Annular Lichen Planus.

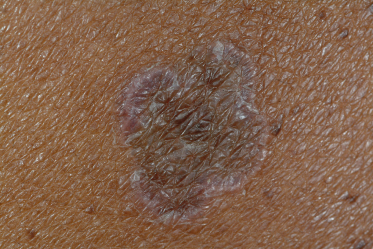

Annular LP is one of the more uncommon clinical variants of LP and is characterized by a ring-like cluster of purple and polygonal flat-topped papules with a clear or atrophic central area (Fig. 85.7). Annular lesions may form through the convergence of multiple lichenoid papules or from the central involution of flat papules or plaques with an expanded, raised border. Annular LP may be found in light and dark skin types [103]. Lesions tend to mimic granuloma annulare and a biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. This variant may be seen in up to 10% of individuals with LP [91,102] and can be found in only a small minority of children with LP [77,78,82,83]. The most common sites of involvement include the axilla and penis followed by the extremities, groin, back and buttocks [103]. The majority of patients are asymptomatic but pruritus and burning can occur.

Atrophic Lichen Planus.

Atrophic LP represents the end-stage or resolving phase of LP where atrophic plaques are seen commonly at the sites of previous plaques of annular or hypertrophic LP. Diagnosis at this stage may prove difficult unless typical-looking LP can be found elsewhere on the skin or mucous membranes. Location may be helpful as atrophic LP usually results from annular or hypertrophic LP occurring most commonly on the lower extremities. A history of potent topical corticosteroid use may also be responsible for, or at least contribute to, the epidermal atrophy.

Acute Lichen Planus.

This form of LP is known for its widespread distribution and its acute, eruptive nature (thus it is also known as exanthematous or eruptive LP). Common locations for acute LP include the trunk, volar wrists and the dorsal extremities and feet. The course is usually self-limited. Children and adults can be affected although reports in children are sparse in the literature [76–80,83,89,152,153]. Drug-related causes should be ruled out in such an extensive lichenoid eruption.

Linear Lichen Planus.

Linear LP has been well described in children. It can sometimes be misdiagnosed in an area of trauma or scratching (a result of the Koebner phenomenon) which can result in linear lesions. However, true linear LP is used to describe those spontaneous eruptions following the lines of Blaschko. Linear lesions can consist of verrucous papules and plaques and are frequently unilateral. A thorough review of the literature by Kabbash et al. reported 20 cases of linear LP following the lines of Blaschko in children [104]. The course in children is self-limited and benign but pruritus can be troublesome and the long-term side-effect of dyspigmentation can be problematic. Cases of adult-onset linear or blaschkoid LP have also been described. The linear LP variant has claimed the misnomer of ‘zosteriform’ LP, but the true distribution is not dermatomal nor does it occur in areas of previous herpes zoster infection due to an isomorphic response [154].

Inverse Lichen Planus.

This unusual LP variant presents in an inverse distribution with violaceous papules and plaques in the intertriginous areas (axilla, inframammary folds and inguinal creases). Less often, lesions may appear in the popliteal and antecubital fossae. Given the hyperpigmentation seen in inverse LP, there may be overlap with LP pigmentosus.

Lichen Planus Pigmentosus.

This variant has been seen mostly in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East [155–157]. LP pigmentosus consists of slate grey to dark black-brown ill-defined macules, papules or patches on sun-exposed (primarily face and neck, extremities) and flexural areas. Areas of pigmentation can become confluent and pigmentation patterns have been classified as diffuse (most commonly), blotchy, reticular or perifollicular [157,158]. Preceding erythema is not present. Scalp, nail and mucous membrane involvement is unusual to rare and symptoms tend to be minimal but pruritus and a burning sensation can occur. In the literature there is conflicting evidence as to the significant clinical and pathological difference between LP pigmentosus and ashy dermatosis (erythema dyschromicum perstans) [159].

Lichen Planus Pemphigoides and Bullous Lichen Planus.

Lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous LP are both rare variants of LP, particularly in children. The undifferentiated usage of these terms has led to confusion in the dermatology literature. Specifically, bullous or vesicular lesions may develop within pre-existing lesions of LP or randomly on uninvolved skin. The former is known as bullous LP and the latter as LP pemphigoides. In patients with LP pemphigoides, it has been demonstrated that there are circulating autoantibodies against the C-terminal of the NC16A domain of the 180 kD BP antigen (BPAG2, type XVII collagen), as in classic bullous pemphigoid, as well as a novel epitope within the BP180 NC16A domain designated MCW-4 [160]. In addition to autoantibodies against the 180 kD antigen, one study also showed circulating autoantibodies directed against a 200 kD antigen [161]. It has been hypothesized that damage to the basement membrane by the lichenoid infiltrate exposes hidden antigens to autoreactive T-cells, triggering autoantibody formation and subsequent formation of bullous/vesicular lesions in LP pemphigoides. In the lesions arising on non-involved skin of LP pemphigoides, subepidermal bullae without a band-like infiltrate exist that may contain eosinophils and neutrophils. The formation of bullous lesions in bullous LP is an end-result of the intensive liquefaction and vacuolation of the basal layer resulting in subepidermal bullae in chronic cutaneous LP lesions. In addition, bullous LP will have negative indirect and direct immunoflourescence studies [162].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree