Fig. 68.2 Typical track of cutaneous larva migrans located on plantar aspect of foot.

Courtesy of Dr Sampaio, Brazil.

Fig. 68.3 Initial reddish multiple papules at sites of larvae penetration.

Courtesy of Dr Sampaio, Brazil.

Fig. 68.4 Typical erythematous serpiginous track of cutaneous larva migrans.

Courtesy of Dr Sampaio, Brazil.

Fig. 68.5 Bacterial secondary infection in a patient with cutaneous larva migrans.

Courtesy of Dr Sampaio, Brazil.

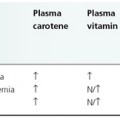

Diagnosis.

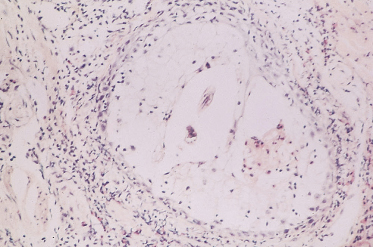

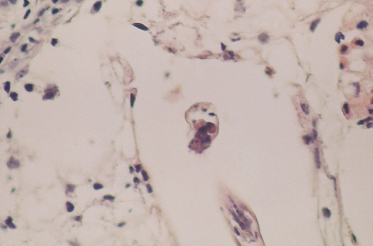

Cutaneous larva migrans is usually a clinical diagnosis based on the typical clinical presentation associated with a travel history or other potential exposure. Blood tests are not specific, and histopathology is rarely needed, particularly since the larvae are usually located several centimetres from the track. Histopathological features include a keratotic epidermis with cavities (Figs 68.7 & 68.8), and an oedematous dermis with mononuclear cells and eosinophils [18]. Eosinophilia and a rise in total serum IgE can occur and might confirm the diagnosis but are not considered diagnostic as only a minority of patients present with these signs [1]. Epiluminescence microscopy to visualize migrating larvae has been used, but the sensitivity of this method in CLM has not yet been systematically evaluated [26].

Fig. 68.7 Inflammatory cell infiltrate surrounding a large burrow with oval and circular structures compatible with nematode larvae (haematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification ×240).

Courtesy of Dr Guedes, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Fig. 68.8 Detail of spherical and oval structures compatible with nematode larvae (haematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification ×400).

Courtesy of Dr Guedes, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnoses include all dermatoses that give rise to creeping eruptions due to the larvae of nematodes (other than hookworms), adult nematodes, larval forms of trematodes, fly maggots and arthropods. From a clinical point of view differential diagnosis does not include parasites whose larvae do not migrate in the skin (cercarial dermatitis, onchocerciasis, dirofilariasis). In case of hookworm folliculitis, bacterial folliculitis has to be ruled out, although this is usually not pruritic [24].

Larva currens caused by infection of Strongyloides stercoralis may be distinguished from CLM by the faster movement of the larva, which travels up to 10 cm per hour. These lesions persist for only a few hours and recur at irregular intervals [27].

Other diseases that evolve with serpiginous skin lesions, such as granuloma annulare, porokeratosis of Mibelli, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other diseases that may mimic CLM, such as scabies, loiasis, myiasis, herpes zoster or phytophotodermatitis, can usually easily be differentiated by history, symptomatology and morphological findings.

Treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree