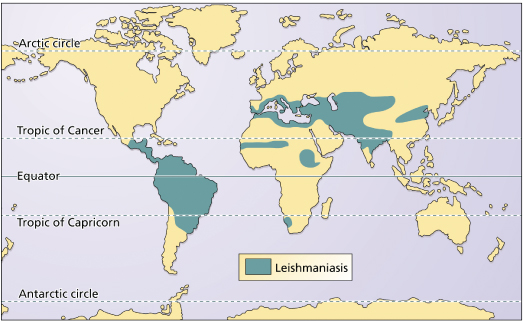

Leishmaniasis represents an important public health problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 350 million people are at risk of infection in the world today [1]. The worldwide annual incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis is around 1.5 million cases, 15% occurring in those under the age of 14 years, with visceral leishmaniasis having an annual incidence of around 500,000 cases, mostly in children under 5 years old. The disease occurs in 82 countries, including 10 developed and 72 developing countries (Fig. 67.2). Notification is compulsory in only 30 of these countries. Undernotification is significant, mainly because of inadequate epidemiological surveillance programmes and the fact that cutaneous disease can resolve spontaneously or pass unnoticed.

History.

The disease owes its name to Sir William Boog Leishman (1865–1926), a British military surgeon who in 1903 described the parasites present in a soldier who died from kala-azar, contracted during his service in the imperial British campaigns in India. In the same year, an Irish doctor also working in India, Dr Charles Donovan, observed intracellular corpuscles in the liver and spleen of a 12-year-old child who had died of a prolonged febrile disease [2], giving his name to the so-called Leishman–Donovan bodies (the amastigotes).

In 1904, Marzinowsky & Borgoff published their observations concerning the oriental sore from Russia, suggesting the name Ovoplasma orientale for the causative agent. In the same year, Mesnil, Nicolle and Remlinger’s description of ‘the Aleppo button’ appeared. This report was followed by various authors’ findings of a variety of sores from different Eastern geographical regions.

In 1908, Nicolle & Sicre obtained pure leishmaniasis cultures from Aleppo sore lesions and noted the similarity with those obtained by Rogers out of samples taken from patients with kala-azar. The name Leishmania tropica was then accepted for the parasite which had been described by Luhe in 1906 [3].

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) existed in America before 1492, as depicted in several pre-Colombian anthropomorphic ceramics found in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, which show typical lesions. This hypothesis is upheld by a number of writings about the conquistadores, such as A Description of the Kingdom of Peru by Baltazar Ramírez and An Illustrated History of Peru, in which the word ‘uta’ appears, referring to the sandflies, as well as to the epidemics of cutaneous ulcers, which existed in the Eastern regions of the Amazon. After the conquest of Peru by Pizarro and his soldiers, some of the Spaniards who had entered various Andean valleys where sandflies existed broke out in ulcers and mutilating nasal lesions, although natives from the so-called ‘wooded zones’ very rarely presented with them [3].

In 1906, Seidelin reported the diffuse form of leishmaniasis (DL) in a patient from the Yucatán peninsula in Mexico. Lindenburg, in 1909, identified the causative agents of the Baurú and Bahía ulcers in Brazil as leishmania. In the same year, Carini & Parankos also reported the demonstration of the parasite in Brazilian patients’ ulcers, which resembled those from the Eastern sore. In 1911, Gaspar Vianna [4] considered that these parasites constituted a new species, which he called L. braziliensis.

In 1926, Montenegro [5] in Brazil developed an intradermic reaction test for leishmaniasis using inactivated promastigotes, a very useful tool for epidemiological surveys and, also, as a diagnostic aid.

It has been claimed that visceral leishmaniasis (VL) was introduced into America by the conquistadores and their dogs infected by L. infantum [6]. There is also a possibility of the entity being authentically American, with the fox and wild canids being the wild reservoir and L. chagasi the aetiological agent. The first description of VL in America is attributed to Migone in Paraguay, in 1913, from his description of a child who died from the disease [6].

Aetiology.

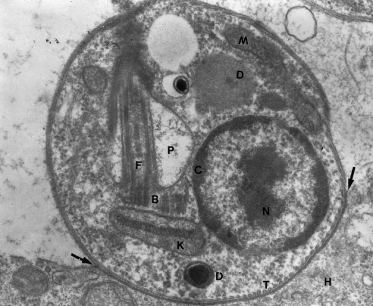

Leishmaniasis is produced by protozoa belonging to the Trypanosomatidae family and the genus Leishmania. They are dysmorphic parasites that live in the macrophages of the vertebrate host as amastigotes, 2–3 µm in diameter, oval or round, with characteristic morphology (Fig. 67.3). In cultures and in the gastrointestinal tract of sandflies, they adopt the promastigote form of an elongated parasite, 15–25 × 3 µm, with a long anterior flagellum. They are transmitted to the vertebrate hosts by the bite of sandflies (Fig. 67.4).

Fig. 67.3 Amastigote of L. amazonensis in human tissue. The arrows point to the amastigote–macrophage junction. B, basal corpuscle (centriole); C, chromatin; D, dense bodies, probably lysosomes; F, flagellum; H, histiocyte cytoplasm; K, kinetoplast; M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus of the amastigote; P, flagellar pocket; T, microtubules.

Research studies have led to the acceptance of two subgenera, Leishmania and Viannia, which are made up of complexes and these, in turn, of species (see Fig. 67.1) [7].

This classification is important in academic and epidemiological terms, as well as for prognosis and treatment. For example, the L. mexicana complex sometimes produces diffuse forms of the disease, whereas the L. braziliensis complex is more resistant to treatment and may cause the mutilating mucosal forms. The species that produce VL can produce ulcerative or nodular skin lesions similar to those produced by other species, affecting children more frequently [8]. This has been demonstrated with L. chagasi [8] and L. infantum, the parasites that produce the majority of cutaneous ulcers in the Mediterranean area [9,10].

Pathogenesis.

Sandflies contain abundant promastigotes in their proboscis. It is advantageous for the vector to get rid of the parasites, injecting them into the host. Promastigotes are inoculated intradermally, 10–200 per bite [9], and penetrate a medium with a different temperature and non-specific defensive factors, such as polymorphonuclear cells or complement. The latter may either damage the parasites or facilitate their phagocytosis by macrophages [11]. Maxadilan, a vasodilator peptide, has been shown to exist in the Lutzomyia longipalpis salival secretion, facilitating the dissemination of L. chagasi [12].

The phagocytic process is essential for the induction of the disease and leads to the transformation of promastigotes into amastigotes, which are much more resistant to the lytic action of macrophages. Amastigotes are obligatory intracellular parasites and the macrophages are their target cells. Once phagocytosed, the amastigotes derive all their needs from the macrophages and resist the respiratory burst and the lytic action of its enzymes [13].

Host immune response to the antigenic macrophage presentation determines the clinical form of the disease. When T lymphocytes are stimulated and a hypersensitivity response is induced with the presence of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes that produce interleukins characteristic of the type 1 T helper cell (Th1) response, localized clinical cutaneous forms are produced [14,15]. When this antigen presentation is different, with a predominant Th2 response, anergic and diffuse nodular forms are produced [14,15]; these are quite rare but occur in some L. amazonensis, L. mexicana and L. aethiopica infections.

Leishmania species have been isolated from peripheral blood leucocytes taken from a patient with MCL [16]. This finding suggests that these circulating cells carry the parasite to the nasal and other mucosal tissues. Parasitized circulating macrophages have been seen in chronic L. braziliensis infections, an indication that metastasis can occur in any phase of the disease [17]. Villela et al. [18] showed that macrophages with amastigotes were present in apparently healthy nasal mucosae from patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). These observations have not been confirmed in more recent studies [19].

Pathology.

The histopathology of leishmaniasis varies with factors such as the specific aetiological agent, the point of evolution when biopsied, ulceration, secondary infection, location of the lesions, previous treatment and the host immune response.

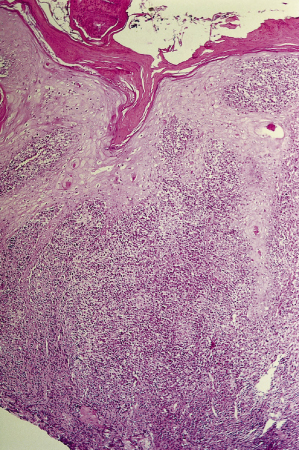

In the skin, initial papular lesions show a dermal nodular or diffuse infiltrate made up of lymphocytes and plasmocytes, with vacuolated subepidermal macrophages containing abundant amastigotes. Older, ulcerated lesions also reveal a characteristic diffuse granulomatous pattern with epidermal hyperplasia (Fig. 67.5). In the dermis and hypodermis, there are also disorganized granulomas formed by epithelioid cells, vacuolated macrophages and abundant plasmacytes and lymphocytes. Giant cells are absent or scanty. Tuberculoid granulomas may be found in more advanced stages of the disease when greater host hypersensitivity has developed. Fibrinoid and caseation necrosis can occasionally be extensive and may resemble the appearance of tuberculosis.

Fig. 67.5 Skin biopsy of leishmaniasis showing crust, epidermal hyperplasia and diffuse dermatitis. Panoramic view (haematoxylin and eosin stain).

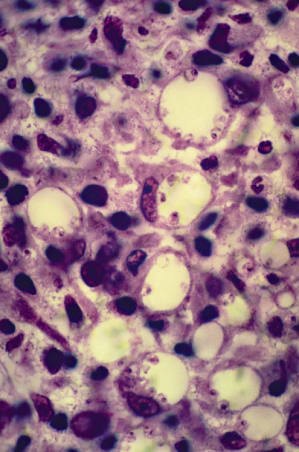

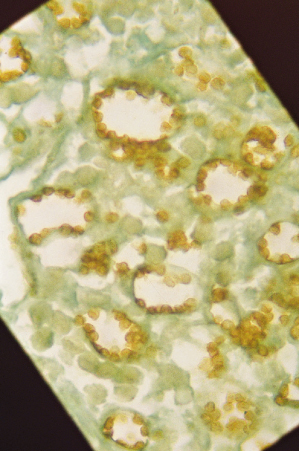

The amastigotes are more easily demonstrated in younger lesions. However, they can usually be observed in up to 80% of skin biopsies. Some of the macrophages in the process of lysis or necrosis are eliminated in the scab covering the ulcer. The parasites adhere to the macrophage phagolysosomic membrane. When numerous, such as in the early stages of the L. brasiliensis complex disease or, even more commonly, in the L. mexicana, L. major and L. tropica lesions and the diffuse forms, they are seen as a crown or wreath in the periphery of the phagolysosome (Figs 67.6, 67.7).

Fig. 67.6 Plastic-embedded, toluidine staining of a leishmaniasis skin biopsy, showing amastigotes attached to the macrophage phagolysosome membranes.

Fig. 67.7 Immunohistochemical staining of Leishmania, with antibodies for the L. mexicana complex in a case of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis.

In lesions produced by the subgenus Viannia, mainly those having an evolution of over 2 months, the macrophages contain few parasites. In some lesions, rich in parasites, it is possible to see keratinocytes with amastigotes in the cytoplasm. Necrotic vasculitis of small and medium-sized vessels is sometimes present in foot and leg ulcers.

In MCL involving mucosal ulceration, severe epithelial hyperplasia is not found, as it depends on hair and eccrine skin components that are absent in these membranes. The inflammation is diffuse with disorganized granulomas that may be tuberculoid, containing large amounts of lymphocytes and plasmocytes. Parasites are shown in about one-half of the biopsies of these lesions [20].

Clinical Features.

The aetiopathogenic criteria, as stated so far, suggest the existence of two broad leishmanial syndromes: cutaneous and visceral [21]. The former also includes the mucosal lesions, called MCL, because they have a primary skin lesion or the mucosal disease has disseminated to neighbouring nasal and upper lip skin.

Typical leishmanial ulcers may be easily diagnosed clinically by an expert. However, epidemiological and laboratory studies are necessary to identify the species of disease-causing parasite. In other words, the clinical appearance does not correlate well with the specific causative parasite species.

References

1 Organización Panamericana de la Salud Organización Mundial de la Salud. Epidemiología, Diagnóstico, Tratamiento y Control de las Leishmaniasis en America Latina. Washington, DC: Organización Panamericana de la Salud Organización Mundial de la Salud, 1994.

2 Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R (eds). The Leishmaniases in Biology and Medicine. London: Academic Press, 1987.

3 León LA. Leishmanias y Leishmaniasis. Quito, Ecuador: Editorial Universitaria, 1957.

4 Vianna G. Sobre uma nova especie de Leishmania. Brasil Med 1911;25:411.

5 Montenegro J. Cutaneous reaction in leishmaniasis. Arch Dermatol Syph 1926;13:187–94.

6 Lainson R. The American leishmaniases: some observations on their ecology and epidemiology. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1993;77:569–96.

7 World Health Organization. Control of the Leishmaniases. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Tech Report Series. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990.

8 Ponce C, Ponce E, Morrison A et al. Leishmania donovani chagasi: new clinical variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Honduras. Lancet 1991;337:67–70.

9 Farah F, Klaus S, Frankenburg S et al. Leishmaniasis and other protozoan infections. In: Fredburg JM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K et al. (eds) Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 6th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999: 2609–19.

10 Bryceson ADM, Hay RJ. Parasitic worms and protozoa. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA et al. (eds) Textbook of Dermatology, 6th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1998: 1410–27.

11 Mosser DM, Edelson PJ. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by Leishmania promastigotes: parasites lysis and attachment to macrophages. J Immunol 1984;132:1501–5.

12 Lerner E, Ribeiro J, Nelson R et al. Isolation of maxadilan, a potent vasodilatory peptide from the glands of the sand fly Lu longipalpis. J Biol Chem 1991;266:112–34.

13 Mauel J. Macrophage–parasite interactions in Leishmania infections. J Leuk Biol 1990;47:187–93.

14 Locksley RM, Louis JA. Immunology of leishmaniasis. Opin Immunol 1992;4:413–18.

15 Tapia FJ, Cáceres-Dittmar G, Sánchez MA et al. The cutaneous lesion in American leishmaniasis: leukocyte subsets, cellular interaction and cytokine production. Biol Res 1993;26:239–47.

16 Bowdre J, Campbell JL, Walker D et al. American mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Clin Pathol 1981;75:435–8.

17 Palau MT, Corredor A. Aislamiento de Leishmania de monocitos Circulantes. Resumenes Cuarto Congreso Latinoamericano de Medicina Tropical. Guayaquil, Ecuador: Sociedad Latinoamericana de Medicine Tropical y Parasitología, 1993.

18 Villela F, Pestana B, Pessoa SB. Presença da ‘Leishmania brasiliensis’ na mucosa nasal sem lesao aparente, em casos recentes de leishmaniose cutanea. O Hospital 1939;16:953–60.

19 Marsden PA. Mucosal leishmaniasis (‘espundia’ Escomel, 1911). Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1986;80:859–76.

20 Rodríguez G, Sarmiento L, Hernández C. Leishmaniasis mucosa y otras lesiones destructivas centrofaciales. Biomedica 1994;14:215–29.

21 Magill AJ. Epidemiology of the leishmaniasis. Dermatol Clin 1995;13:505–23.

Cutaneous Syndromes

Localized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCD) is the most frequent clinical form in both children and adults. It most commonly affects exposed areas of the body, such as the face and the extremities (Figs 67.8–67.12), although it may involve any part of the body. Scalp involvement is rare. Over 60% of children have single lesions. Extensive ulcers and multiple lesions may also occur (see Fig. 67.10) and may appear at different times.

Fig. 67.10 A 1-year-old child with multiple severe lesions produced by L. braziliensis. Notice the nose skin involvement, with extension into the nasal mucosa.

Courtesy of Dr Mariano López, Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia.

Fig. 67.11 Intense erythematous appearance, with crusted lesion of the nose. This lesion may easily extend inside the nose.

At the site of parasite inoculation, a discrete inflammation is slowly established, which turns into a papule, nodule or plaque after an incubation period that ranges between 2 weeks and 12 months, depending on the species of Leishmania and the amount of inoculated parasite.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree