The incubation period is variable and not well defined, lasting for weeks to years. Initially, some individuals may report a feeling of pain at the site, while others may not recall any direct trauma [1]. The infection starts with a papule, nodule or localized subcutaneous inflammation that progressively enlarges to form abscesses and sinus tracts draining to the skin (Fig. 63.2).

Drainage is serous, serosanguinous or purulent and contains the typical grains of varied colour and size depending on the causative agent. The grains are aggregates of fungal hyphae or bacterial filaments, and their size, colour and consistency provide the initial clue to the causative species [7]. Black grains are suggestive of eumycotic mycetoma (Exophiala, Madurella, Leptophaeria); white or light-coloured grains are seen in either actinomycotic or eumycotic mycetoma, such as Acremonium or Pseudoallescheria species. Infection gradually spreads through fascias to deep structures, including bone, producing variable destruction. Overlying skin becomes indurated and fixed, with decreased mobility due to a painless swelling and lymphoedema. Scarring and fibrosis of the affected tissues are common.

Actinomycetomas characteristically progress more rapidly than eumycetomas and their lesions are more inflammatory and destructive. Eumycetomas grow more slowly and the lesions have more clearly defined margins and remain encapsulated for a long time [4].

Differential Diagnosis.

Botryomycosis is a staphylococcal infection with large, red lilaceous and painful nodules; other diseases to consider are sporotrichosis, chronic osteomyelitis, chromomycosis, furunculoid lesions and other non-infectious soft tissue tumours such as lipoma, fibroma or sarcomas [1].

Pathology.

Biopsy of mycetoma lesions reveals granules in abscesses with specific tinctorial characteristics suggestive of the causative species. In the centre of abscesses with necrotic polymorphonuclear cells are grains surrounded by epithelioid cells, macrophages and giant cells, with variable fibrosis [8]. In the chronic stages of eumycotic mycetoma, neutrophils disappear and are replaced by a foreign body-type granuloma. Tissue, Gram’s or fungal stains allow the identification of the causative organism in the centre of the lesions.

Laboratory Studies.

Imaging studies enable the degree of extension of the infection to be assessed. Radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging studies may detect bony lesion and soft tissue involvement. Ultrasound imaging can also differentiate between an actinomycetoma and eumycetoma depending on the pattern of hyper-reflective echoes produced by the grains.

Serological tests, such as immunoelectrophoresis, immunodiffusion and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) are also used, although they are not always sensitive and can be prone to cross-reactivity [4].

Culture of the grains in Sabouraud’s medium or blood agar allows identification of the organism, and microscopic and biochemical studies of the colonies help to determine their species. The sample can be obtained from any open sinus by direct extraction, fine-needle aspiration or by deep surgical biopsy. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology is now able to identify causative species where culture methods have failed. The correct species identification is imperative in order to start appropriate drug treatment and for epidemiological studies [1,7].

Treatment.

Management of mycetoma depends on the causative organism. Eumycetomas are managed by long courses of a systemic antifungal, typically 18–24 months or even longer, combined with aggressive surgical excision or debulking of the lesions. Ketoconazole, itraconazole and new azoles such as posaconazole and voriconazole are effective against some fungi; amphotericin B [9] is effective against other agents. Drug treatment is given before surgery to decrease lesion size, and continued afterwards to ensure complete clearance of infection. Nonetheless, relapse rates of 20–90% have been reported [4,7].

Actinomycetomas respond more favourably to drug therapy than eumycetomas, but the cure rates can vary widely from 60 to 90%. Combined drug treatment is preferred to prevent the development of drug resistance and to eradicate any residual infection [7]. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is the drug of choice. Amikacin plus clavulanic acid is also effective in the vast majority of cases, and there are now preliminary data for the efficacy of the oxazolidinones or imipenem for the management of resistant or severe cases [4]. In case of deep invasion and bone destruction, amputation of the affected limb is necessary. Treatment periods are characteristically long, with the mean duration of treatment being more than a year, and it must be prolonged well beyond apparent clinical cure because of the risk of recurrence. Cure may be defined by a lack of clinical activity, absence of grains and negative cultures [7].7

Prognosis.

Poor response to therapy and chronic progression indicate a bad prognosis.

References

1 Lichon V, Khachemoune A. Mycetoma: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2006;7:315–21.

2 Pilsczek FH, Augenbraun M. Mycetoma fungal infection: multiple organisms as colonizers or pathogens? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2007;40:463–5.

3 Khatri ML, Al-Halali HM, Fouad Khalid M et al. Mycetoma in Yemen: clinicoepidemiologic and histopathologic study. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:586–93.

4 Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008;9:2077–85.

5 Baddley JW, Stroud TP, Salzman D et al. Invasive mold infections in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1319–24.

6 Bonduel M, Santos P, Turienzo CF et al. Atypical skin lesions caused by Curvularia sp. and Pseudallescheria boydii in two patients after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;27:1311–13.

7 Ameen M, Arenas R. Developments in the management of mycetomas. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:1–7.

8 Fahal AH, el-Toum EA, el-Hassan AM et al. The host tissue reaction to Madurella mycetomatis: new classification. J Med Vet Mycol 1995;33:15–17.

9 Poncio Mendes R, Negroni R, Bonifaz A, Pappagianis D. New aspects of some endemic mycoses. Med Mycol 2000;38(Suppl. 1):237–41.

Mycoses Due to Dematiaceous Fungi

These are mycoses due to fungi belonging to the family Dematiaceae, characterized by dark-pigmented compounds. Chromomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis and some cases of mycetoma are included in this group.

Chromomycosis (Chromoblastomycosis)

Definition.

Chromomycosis (chromoblastomycosis) is a clinical syndrome caused by several genera of filamentous dimorphic fungi of the family Dematiaceae (with melanic-type pigment in their wall). It is a chronic granulomatous cutaneous disease that is exceptionally rare in children [1,2].

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

The most common agent of chromomycosis is Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Other agents isolated are Cladosporium carrionii, Fonsecaea compactum, Phialophora verrucosa, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa [3]. It has been recognized that a single fungus may cause more than one type of clinical manifestation, therefore some of these fungi are also responsible for other subcutaneous mycoses, such as mycetoma and phaeohyphomycosis, depending on the habitat conditions and the host response. The fungal elements are distributed in soil and organic material worldwide, but they predominate in rural areas of tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas and Africa, such as Madagascar, Brazil, Venezuela and Mexico [4]. The infection is acquired through accidental cutaneous wounds.

Clinical Features.

Chromomycosis affects rural workers and people on holiday in endemic areas, with a predilection for men, and occurs only rarely in children, usually those over 3 years of age [5]. From the site of inoculation, the lesion usually restricts itself to cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue [6]. It is characterized by an asymptomatic pink, scaly papule, usually on the feet or lower limbs, which appears several months after inoculation. These papules slowly enlarge to become nodules or ulcerated verrucous plaques, and they develop satellite lesions, resulting in large, vegetating tumours. The latter were the cause of the name ‘dermatitis verrucosa’ used in old texts. Bleeding is common, and in the presence of bacterial overinfection, the nodules become painful and pruritic. Satellite lesions frequently form by self-inoculation, or spread via the lymphatic system [3]. The median incubation period is not known; however, most cases progress slowly, over many years and sometimes decades [7]. There is no discharge of ‘grains’ and no bone involvement, but scarring of lymphatic vessels resulting in lymphoedema can occur. Metastatic spread to other organs is reported but clearly represents a decided minority of cases [8].

Differential Diagnosis.

Chromoblastomycosis may mimic several dermatoses. In the initial stages, chromomycosis should be distinguished from other chronic granulomatous disorders such as tuberculosis, sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis and blastomycosis; when fully established, mycetoma and cutaneous carcinomas are the main diagnoses to consider.

Pathology.

Under a hyperkeratotic pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplastic epidermis with occasional microabscesses there is a granulomatous infiltrate rich in macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells. In the scales and the dermis, ‘fumagoid bodies’ (also known as sclerotic bodies, muriform cells, copper pennies, Medlar bodies and chlamydospores) can be observed. They are round to polyhedral, dark, thick-walled fungal cells, 5–12 µm in diameter, and characteristic of chromoblastomycosis. They may occur either within macrophages and giant cells or extracellularly. Fibrous tissue is abundant in long-standing lesions [3].

Laboratory Studies.

Material is obtained by scraping or biopsy of the lesions, and culture in Sabouraud’s agar medium produces slow-growing, velvety, dark-green, brown or grey colonies; microscopic appearance of the conidia formation identifies the species [8].

Treatment.

The treatment modalities are divided into three groups: surgery, physical modalities and systemic antifungal medications depending on the stage of the disease [8].

The best therapeutic approach when the lesion is limited is surgical excision, CO2 laser therapy or cryotherapy [6,8–10]. For more extensive cases, systemic antifungal drugs (itraconazole, terbinafine) are recommended either as monotherapy or in combination. Treatment should be continued until clinical resolution, which usually occurs after several months of therapy, with cure rates up to 91% [9]. Relapse is common in the most extensive lesions [8]. In disseminated chromomycosis, amphotericin B, terbinafine and itraconazole monotherapy or in combination with oral 5-flucytosine, have been used with some success [6,11] New second-generation triazoles (voriconazole, ravuconazole, posaconazole) with in vitro activity against the black fungi may also be useful in the treatment of chromomycosis [9].

Prognosis.

Chromomycosis is a chronic disease with a moderate degree of morbidity and exceptionally visceral dissemination. It also has potential association with epidermoid carcinoma [6].

References

1 Aceves-Ortega R. Deep mycosis in children. Mod Prob Pediatr 1975;17:228–41.

2 Caputo RV. Fungal infections in children. Dermatol Clin 1986;4:137–49.

3 Tomson N, Abdullah A, Maheshwari MB. Chromomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:239–41.

4 Fenniche S, Zaraa I, Benmously R et al. Chromomycosis: a new Tunisian case report. Int J Infect Dis 2005;9:288–9.

5 Mohamed KN. Verrucous lesions in children in the tropics. Ann Trop Pediatr 1990;10:273–7.

6 Ezzine-Sebaï N, Benmously R, Fazaa B, Chaker E, Zermani R, Kamoun MR. Chromomycosis arising in a Tunisian man. Dermatol Online J 2005;11:14.

7 Mouchalouat M de F, Galhardo MC, Fialho PC, Coelho JM, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Valle AC. Cladophialophora carrionii: a rare agent of chromoblastomycosis in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2008;50:351–3.

8 Sayal SK, Prasad GK, Jawed KZ, Sanghi S, Satyanarayana S. Chromoblastomycosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:233–4.

9 Tsianakas A, Pappai D, Basoglu Y et al. Chromomycosis – successful CO2 laser vaporization. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:1385–6.

10 Hira K, Yamada H, Takahashi Y et al. Successful treatment of chromomycosis using carbon dioxide laser associated with topical heat applications. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:273–5.

11 Kumarasinghe SP, Kumarasinghe MP. Itraconazole pulse therapy in chromoblastomycosis. Eur J Dermatol 2000;10:220–2.

Phaeohyphomycosis

Definition.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a general term used to describe mycotic infections caused by dematiaceous fungi with pigmented cell walls, which grow as darkly pigmented colonies [1]. These are uncommon causes of human disease, but can be responsible for life-threatening infections [2].

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

Dematiaceous fungi are pigmented yeast-like moulds that develop in tissue under filamentous or non-branching forms. They are commonly found in the soil and are distributed worldwide [2]. Over 100 species and 60 genera have been reported to cause infections in humans. The common characteristic of all these species is the presence of melanin in their cell walls, which imparts the dark colour to their conidia or spores and hyphae [2]. The most common agents found in the cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are Exophiala spp., Alternaria spp., Phialophora spp. and Bipolaris spp. Phaeoannellomyces werneckii (formerly called Cladosporium werneckii or Exophiala werneckii) is the agent responsible for tinea nigra. Other organisms produce onychomycosis (Onychocola spp. and Alternaria spp.). Brain abscesses are commonly caused by Cladophilaphora spp. Ramichloridium spp., Curvularia spp. and Bipolaris spp. are the fungal genera most commonly associated with allergic sinusitis. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis is an increasingly common infection mainly due to Scedosporium prolificans, Bipolaris spp. and Wangiella spp. [2–4].

Clinical Features.

The clinical syndromes of phaeohyphomycosis include cutaneous disease (superficial, dermal or subcutaneous), allergic conditions such as fungal allergic sinusitis, and disseminated infection, often characterized by brain abscess formation. Superficial infections are the most common form of infection caused by dematiaceous fungi [5].

Cutaneous disease occurs through accidental inoculation by wood or soil objects. A latency period of several months (or even years) is sometimes observed between the wound and the clinical manifestations [6]. Cutaneous lesions typically occur on exposed areas of the body and often appear as isolated cystic or papular lesions. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk for subsequent dissemination. Occasionally infection also may involve joints or bone [2]. Primary non-cystic phaeohyphomycosis is rare and observed in immunosuppressed hosts [7]. The best known of these infections is the so-called alternariosis, characterized by nodules and inflammatory plaques mimicking granulomatous or suppurative cellulitis, or even ulcers. Dematiaceous fungi are also rare causes of onychomycosis [6].

Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis follows aspiration of spores and produces primary pulmonary infection. The disease spreads by haematogenous dissemination to the skin, central nervous system and other organs. Dematiaceous moulds are also important causes of invasive sinusitis and allergic fungal sinusitis. Infection follows inhalation of spores, and patients usually present with chronic sinus symptoms that are not responsive to antibiotics [2].

Differential Diagnosis.

Tinea nigra must be distinguished from melanocytic lesions; disseminated phaeohyphomycosis must be distinguished from other opportunistic infections.

Pathology.

A granulomatous inflammation with or without abscess and dematiaceous fungal elements in tissue are observed on haematoxylin–eosin staining (HE). Fungal elements are also visible on periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain, and they also stain strongly with the Fontana–Masson stain, which is specific for melanin [2,8].

Laboratory Studies.

To differentiate between an environmental contamination and a true infection, deep samples are required. Black-grey yeast-like colonies are noted on the culture from biopsied tissue. Definitive molecular techniques employing ribosomal DNA sequencing are now available for species identification [5,6,8].

Treatment.

Surgical excision alone or associated with topical azole derivatives is the mainstay of therapy for the localized forms. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis is difficult to treat because of its resistance to antifungals, but promising results have been obtained with itraconazole, liposomal amphotericin B and voriconazole [9]. Length of therapy is generally based on clinical response and ranges from several weeks to several months or longer [2].

Prognosis.

This depends on the underlying disease. The mortality rate in disseminated phaeohyphomycosis is greater than 70% despite aggressive antifungal therapy, and there are no antifungal regimens associated with improved survival in disseminated infection [2].

References

1 Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin 1996;14:147–53.

2 Revankar SG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2006;20:609–20.

3 Fleming RV, Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ. Emerging and less common fungal pathogens. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2002;16:915–33.

4 Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:467–76.

5 Harris JE, Sutton DA, Rubin A, Wickes B, De Hoog GS, Kovarik C. Exophiala spinifera as a cause of cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis: case study and review of the literature. Med Mycol 2009;47:87–93.

6 Dubois D, Pihet M, Clec’h CL et al. Cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis due to Alternaria infectoria. Mycopathologia 2005;160:117–23.

7 Moneymaker CS, Shenep JL, Pearson TA et al. Primary cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis due to Exserohilum rostratum (Drechslera rostrata) in a child with leukemia. Pediatr Infect Dis 1986;5:380–2.

8 Suh MK. Phaeohyphomycosis in Korea. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 2005;46:67–70.

9 Barbaric D, Shaw PJ. Scedosporium infection in immunocompromised patients: successful use of liposomal amphotericin B and itraconazole. Med Pediatr Oncol 2001;37:122–5.

Mycoses Due to Dimorphic Fungi

Dimorphic fungi are characterized by their different morphology in the parasitic and saprophytic states. The parasitic (tissue) state is represented by yeast spores with multiple or single buds, whereas the saprophytic (natural) state is represented by its existence as a mould. Mycoses in this group include blastomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, sporotrichosis and penicilliosis.

Blastomycosis

Definition.

Blastomycosis, also known as Gilchrist disease or North American blastomycosis, is a chronic granulomatous disease of the lungs, skin and subcutaneous tissue produced by the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis [1].

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

The fungus grows as a non-pathogenic mould in soil, and its conidia convert to pathogenic yeasts in the host [2]. Blastomyces dermatitidis has been associated with occupational and recreational activities, frequently along streams or rivers that result in exposure to moist soil enriched with decaying vegetation [3]. The endemic areas include the central eastern and mid-western USA, Central and South America, and isolated regions of Asia and Africa.

Blastomycosis affects mainly adult men in rural areas, and outbreaks in cats and dogs have been linked to human cases on some occasions [4]. Rare human-to-human transmission has been observed in female sexual partners of men with blastomycosis disseminated to the prostate gland, in postmortem transmission at autopsy and in transplacental infection of newborns [2].

Children are rarely infected by this agent, and in contrast to other fungal infections usually seen in immunocompromised patients, B. dermatitidis is a true pathogen that often infects immunocompetent individuals [2].

The infection is acquired by inhalation of B. dermatitidis. Cutaneous inoculation is found in laboratory workers who are accidentally exposed to the fungus.

Clinical Features.

The clinical spectrum of blastomycosis is varied; including asymptomatic infection, acute or chronic pneumonia, and disseminated disease. All patient age groups are susceptible but only 3–11% of reported cases occur in patients under 20 years of age [3,5]. In children, the disease tends to be acute and febrile, with higher morbidity and mortality rates [6,7].

Following an incubation period of up to 6 weeks, pulmonary blastomycosis develops, although asymptomatic infection occurs in at least 50% of cases. Acute pulmonary disease mimics community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, and typically resolves spontaneously. Chronic pulmonary blastomycosis is an indolent process that tends to progress insidiously with clinical manifestations that are indistinguishable from tuberculosis, other fungal infections and cancer [3,8]. Only a few patients experience disseminated disease, where the skin and subcutaneous tissue are the most common sites of extrapulmonary involvement, followed by bones and joints, the genitourinary tract and the central nervous system [3,5,9,10].

Cutaneous blastomycosis develops during the course of pulmonary disease. It is the second most common manifestation of blastomycosis, and is seen in approximately 60% of patients. In some cases, the primary pulmonary focus may resolve before the cutaneous manifestation appears [5,8,10]. The skin lesions may be single or multiple and may affect any part of the body [5]. There are nodules, papules or papulovesicles, red to purpuric, which enlarge and ulcerate or become vegetating or crusted plaques. Sometimes there are verrucous crusted lesions with active, arciform, sharply sloped borders and lilac margins, and a tendency to central healing with a thin atrophic hypopigmented scar. Occasionally, the nodules are firm and subcutaneous, with multiple small pustules over the surface that become abscesses and fistulize through the overlying epidermis. Erythema nodosum may be associated with pulmonary blastomycosis.

Primary cutaneous blastomycosis (also known as inoculation blastomycosis) is a rare infection as a result of either injuries sustained in the pathology or microbiology laboratory or an animal bite. After inoculation, an erythematous, indurated area with a chancre appears in 1–2 weeks, with a strong tendency for spontaneous recovery [10]. Painful lymphadenopathy and lymphangitis is associated.

It is difficult to distinguish cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis from secondary cutaneous blastomycosis with a transitory or subclinical pulmonary focus. The induration and chancre formation, and frequent spontaneous resolution, can be used to clinically differentiate this condition. The lack of lymphadenopathy, the prolonged, progressive course of the lesion, and the absence of a history of penetrating injury suggest that the lesion has arisen from dissemination of an asymptomatic pulmonary infection [2,9].

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis is wide and includes scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, tertiary syphilis, leprosy, bacterial pyoderma, pyoderma gangrenosum, leishmaniasis and other fungal infections (sporotrichosis, chromomycosis and paracoccidioidomycosis) [2,5,10].

Pathology.

Histopathological examination of tissue specimens with use of methenamine silver or PAS stain is the usual diagnostic method for extrapulmonary disease [3]. Blastomycosis is characterized by a granulomatous reaction with the formation of microabscesses and the presence of giant cells. These cells may contain numerous spores of the fungus [1].

Laboratory Studies.

Potassium hydroxide smears of the purulent discharge of a lesion often demonstrate characteristic thick double-walled, round yeast. Fungal cultures require a 2–4-week incubation period for growth. The organism grows as a slow-growing brown, wrinkled yeast colony at body temperature (37°C) and a mycelial form at room temperature (25°C), producing a white, fluffy colony on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Serological tests for blastomycosis have low sensitivity and specificity [2,5].

Treatment.

The decision to treat patients with blastomycosis involves consideration of the clinical form and severity of disease, the immune status of the patient, and the toxicity of the antifungal agent. Itraconazole is the drug of choice to treat mild-to-moderate disseminated disease without CNS involvement. For disseminated CNS blastomycosis, life-threatening infections and infections in immunocompromised hosts or pregnant women, intravenous amphotericin B is recommended [2,3,11]. The newer azole antifungal agents, voriconazole and posaconazole, appear to have some promise in the treatment of blastomycosis but experience in humans is limited [3].

Prognosis.

Recurrences are frequent and follow-up must be maintained for years. With current therapies, fatal outcomes due to blastomycosis have become extremely rare.

References

1 Body BA. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic mycoses. Dermatol Clin 1996;14:125–35.

2 Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, Maize JC, Thiers BH. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:824–30.

3 Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1801–12.

4 Lemos LB, Guo M, Baliga M. Blastomycosis: organ involvement and etiologic diagnosis. A review of 123 patients from Mississippi. Ann Diagn Pathol 2000;4:391–406.

5 Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, Kumar Singh S, Chander R, Kawatra N. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol 2009;37:119–21.

6 Schutze GE, Hickerson SL, Fortin EM et al. Blastomycosis in children. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:496–502.

7 Steele RW, Abernathy RS. Systemic blastomycosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis 1983;2:304–7.

8 McKinnell JA, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis: new insights into diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Clin Chest Med 2009;30:227–39.

9 Ross JJ, Keeling DN. Cutaneous blastomycosis in New Brunswick: case report. Canadian Med Assoc J 2000;163:1303–5.

10 Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath BP. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J 2003;9:19.

11 Linden P, Williams P, Chan KM. Efficacy and safety of amphotericin B lipid complex injection (ABLC) in solid-organ transplant recipients with invasive fungal infections. Clin Transplant 2000;14:329–39.

Paracoccidioidomycosis

Definition.

Paracoccidioidomycosis, also known as South American blastomycosis or Lutz–Splendore–Almeida disease, is a chronic granulomatous infection of the mucous membranes and the skin produced by the dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, endemic to South America.

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is a dimorphic fungus found in rural areas of South America, mainly in Brazil, Argentina [1], Venezuela and Colombia [2]. Sporadic cases have been reported in the USA, European countries, and Japan in individuals coming from endemic areas. Paracoccidioidomycosis is infrequent in children and young adults. Some 80–90% of affected individuals are men between 29 and 40 years old, predominantly rural workers from endemic areas, and there is a male:female ratio of 15:1. About 10 million people are infected, 2% of whom will develop the disease [3].

Paracoccidioidomycosis is usually acquired by inhalation of the spores, but the skin and the oropharyngeal mucous membrane are also inoculation sites, following trauma with contaminated materials. Penetration of the fungus may also occur by ingestion, and the lesion will occur in the intestinal mucous membrane [4]. There is no evidence of human-to-human transmission. The incubation period is extremely variable, from weeks to years [5]. There is a correlation of T-cell depression with the severity of paracoccidioidomycosis, and hormonal, genetic and nutritional factors must play a role in the development of the infection and clinical disease [4].

Clinical Features.

The paracoccidioidomycosis infection due to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis can resolve spontaneously, progress to disease, or remain latent, according to the host’s immunity [3]. Two clinical forms of paracoccidioidomycosis are currently recognized: the acute juvenile form and the chronic adult form.

Acute Juvenile Paracoccidioidomycosis

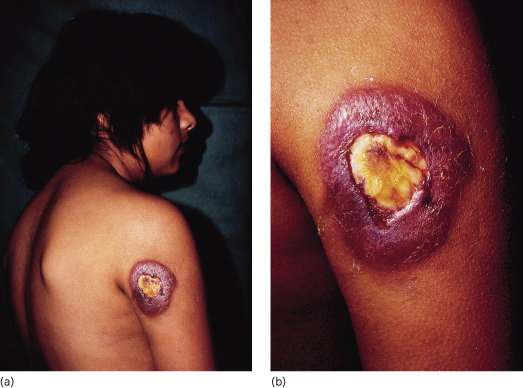

The acute form affects mainly children and adolescents, rapidly and severely involving the monocytic phagocytic system [4]. It represents 5–10% of clinical cases of paracoccidioidomycosis [6] and is the result of extrapulmonary infection associated with severe cell-mediated immunity depression. The disease is severe with high fever, malaise and weight loss, and the organs affected are the liver, spleen, lymphatic system, skin and bone (Fig. 63.3a,b) [6,7]. Oral manifestations, expressed by erythema and oedema, gingival recession and tooth losses, may be the only sign of the disease [8]. The lethality rate in this group is about 11% [3].

Fig. 63.3 (a,b) South American blastomycosis in a 14-year-old girl who died from central nervous system involvement 10 days after these photographs were taken.

Courtesy of Professor Roberto Biagini, Salta, Argentina.

Chronic Adult Paracoccidioidomycosis

Chronic adult paracoccidioidomycosis represents more than 90% of cases and occurs in adults, usually older than 20 years [3]. It is the result of primary pulmonary infection and it can be indolent and self-limited, or chronic and progressive. The first signs of the disease are due to haematogenous dissemination to the lips, mouth, nose and pharynx. The oral lesions typically show an erythematous finely granular hyperplasia, speckled with pinpoint haemorrhages, and a mulberry-like surface called ‘moriform’ stomatitis. Areas of ulceration covered by necrotic material or exudates are common (Fig. 63.4). Involvement of the lips causes a pronounced increase in thickness and consistency (Figs 63.5 & 63.6) [4]. Ulceration and destruction of the uvula, epiglottis and palate are all signs of the progressive disease. The involvement of the larynx can produce dysphasia and destruction of the vocal chords. Tracheal lesions can cause respiratory tract obstruction, and eventually tracheotomy may be needed [3,4].

Fig. 63.5 South American blastomycosis: ulcerated and crusted facial lesions in a boy.

Courtesy of Professor Martins Castro, Brazil.

Fig. 63.6 South American blastomycosis: severe granulomatous lesions in a boy.

Courtesy of Professor Martins Castro, Brazil.

Cutaneous lesions present as ulcers or vegetations, and almost always reproduce the fine granulations and haemorrhagic dots of the mucous lesions [3].

Regional lymphadenopathy is always present. Lymph nodes enlarge and are painful and adherent to the overlying skin; on occasions they can progress to chronic sinuses that suppurate.

Differential Diagnosis.

The main differential diagnoses of oral lesions are squamous cell carcinoma, leishmaniasis, tuberculosis and syphilis. Sarcoidosis and Wegener granulomatosis must also be considered. Lymphangitic forms simulate tuberculosis and Hodgkin disease. Diffuse skin eruptions may simulate syphilis, psoriasis and lymphomas, and localized cutaneous lesions should be differentiated from leishmaniasis, sporotrichosis, tuberculosis and chromomycosis [3,9].

Pathology.

Histology shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepithelial microabscesses, and a granulomatous reaction. P. brasiliensis is found in the tissues, frequently in multinucleated giant cells, but also in the microabscesses [4]. It is seen as large spores with a diameter of up to 60 µm that develop multiple buds in their periphery, giving the characteristic ‘pilot’s wheel’ configuration.

Laboratory Studies.

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis grows very slowly in special media with antibiotics. Serological examination by immunodiffusion or complement fixation and skin tests with paracoccidioidin is used mainly for epidemiological studies or as a parameter to monitor treatment [4]. The technique of double immunodiffusion, because of its sensitivity of over 80% and specificity of over 90%, has been considered the main tool for the diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis [3]. Molecular identification of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis has been done successfully by immunohistochemistry and PCR amplification of ribosomal DNA [4].

Treatment.

Spontaneous cure is not frequently seen in paracoccidioidomycosis, except in some cases of primary lung infections [3]. Treatment includes sulphonamides, amphotericin B or imidazoles. Oral itraconazole is considered the drug of choice, but fluconazole and ketoconazole are also used [4]. However, with these drugs relapses have been observed in 8–25% of patients [10]. Voriconazole is a useful alternative, mainly in cases of neuroparacoccidioidomycosis. No consensus exists on the duration of treatment. It is suggested that patients who have the moderate acute form, or a light or moderate chronic form, should be treated for 2 years and the severe cases of both forms should receive individualized treatment [3].

Prognosis.

The acute juvenile form can lead to death in a few months if untreated. In chronic forms sequelae are caused by the chronic inflammatory process. Pulmonary fibrosis and skin and mucous membrane involvement, with voice alterations (dysphonia), laryngeal obstruction, reduction of the oral commissure, and synechia of the buttocks can be present in these patients [3].

Prevention.

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis has a complex antigenic structure but the 43 kDa glycoprotein is considered specific to P. brasiliensis. Its production occurs during the fungal infection phase. DNA-based vaccination with the gp43 gene product has been tested in mice, eliciting a protective immunity against P. brasiliensis [3,4].

References

1 van Gelderen de Komaid A, Duran EL. Histoplasmosis in northwestern Argentina. II. Prevalence of histoplasmosis capsulati and paracoccidioidomycosis in the population south of Chuscha, Gonzalo and Potrero in the province of Tucuman. Mycopathologia 1995;129:17–23.

2 Cadavid D, Restrepo A. Factors associated with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection among permanent residents of three endemic areas in Colombia. Epidemiol Infect 1993;111:121–33.

3 Ramos-e-Silva M, Saraiva L do E. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Dermatol Clin 2008;26:257–69.

4 Almeida OP, Jorge Junior J, Scully C. Paracoccidioidomycosis of the mouth: an emerging deep mycosis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14:268–74.

5 Body BA. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic mycoses. Dermatol Clin 1996;14:125–35.

6 Vedoya MC, Medvedeff MG, Mereles BE, Chade ME, Lorenzati MA, Thea AE. Paracoccidioidomycosis in a four-year-old boy. Rev Iberoam Micol 2008;25:52–3.

7 Benard G, Orii NM, Marques HH et al. Severe acute paracoccidioidomycosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994;13:510–15.

8 Migliari DA, Sugaya NN, Mimura MA et al. Periodontal aspects of the juvenile form of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1998;40:15–18.

9 Jham BC, Fernandes AM, Duraes GV, Chrcanovic BR, Souza AC, Souza LN. The importance of intraoral examination in the differential diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2008;74:946.

10 Mayayo E, López-Aracil V, Fernández-Torres B, Mayayo R, Domínguez M. Report of an imported cutaneous disseminated case of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Iberoam Micol 2007;24:44–6.

Coccidioidomycosis

Definition.

Coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever, is a mycotic disease caused by Coccidioides immitis and the newly proposed phylogenetic species Coccidioides posadasii [1]. The fungus affects primarily the lungs and occasionally the skin and other organs.

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

Coccidioides spp. are a dimorphic fungus, occurring as a soil saprophyte in the semiarid regions of the southwestern USA, Mexico, and Central and South America [1]. Cases of coccidioidomycosis may also arise outside endemic areas, related to a recent visit to an endemic area or infection through exposure to fomites from such an area [2]. This genus has recently been divided on the basis of genomic analyses into two species, C. immitis (isolates from California) and C. posadasii (formerly known as non-California). There is no obvious difference in the disease states produced by these two species [3,4].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree