62 Finger (PIP/DIP) Collateral Ligament Repair

Abstract

Finger collateral ligament injuries are frequently treated by hand surgeons. Collateral ligament injuries to the fingers are common but most can be treated nonoperatively. Joint instability and joint incongruency, which have failed conservative treatment, are indications for surgical intervention.

62.1 Description

The collateral ligaments of the finger joints are one of the most commonly injured structures in the hand and are often associated with joint dislocations. Stability of the joint should always be tested, both actively and passively, and radiographic evaluation of joint congruency is essential. The most commonly injured joint in the finger is the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, with the incidence being 37.3 per 100,000 a year in the United States. 1 Ligamentous injury to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint is rare due to increased stability from the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon and terminal extensor tendon. Sequelae of a missed joint disruption includes joint stiffness, joint pain, swelling, early degenerative changes, and ultimately loss of function.

62.2 Anatomy

PIP joint stability is afforded through bony constraints, capsule, tendons, and collateral ligaments which allow for a 110-degree arc of motion.

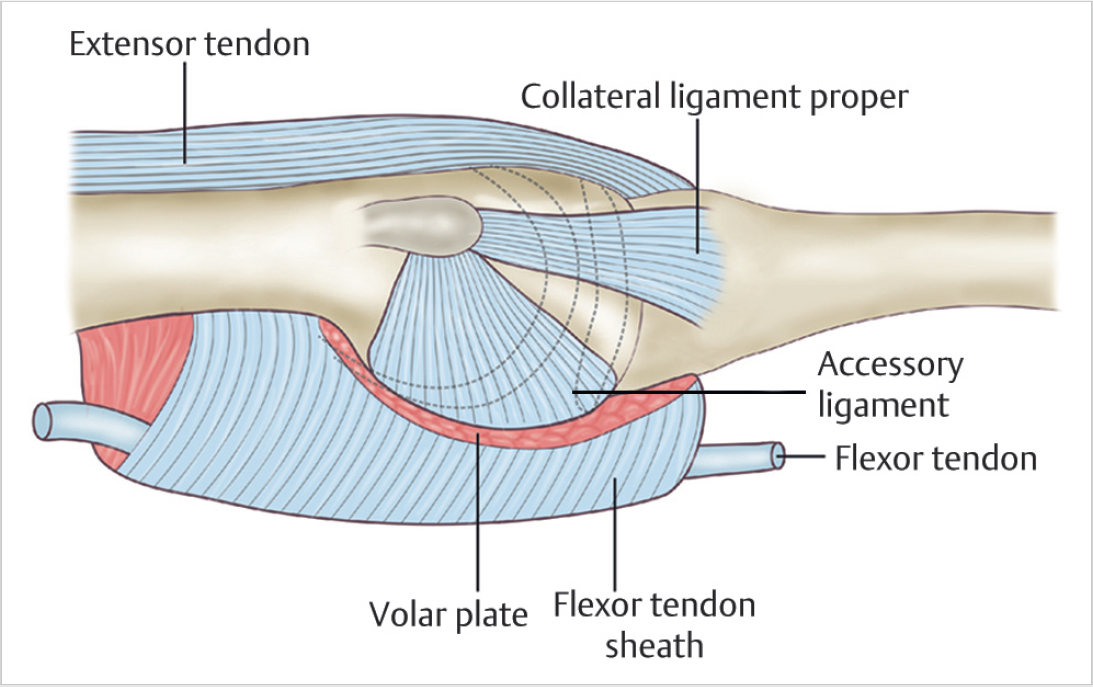

The lateral stability of the joint is provided by the radial and ulnar collateral ligaments. Collateral ligaments comprise “proper” and “accessory” fibers, confluent with one another but differentiated by their insertion point. The proper ligament inserts volarly on the lateral tubercle of the middle phalynx and has a dorsal and volar edge. The dorsal part runs parallel to the middle phalanx, while the volar aspect fans out obliquely to its insertion point. 2 The accessory ligament is flimsy, travels obliquely, and inserts directly into the volar plate, adding to the stability of this volar structure. The proper ligaments are taut in flexion and slack as the joint comes into extension, due to its more dorsal attachment. In contrast, the accessory component tightens in extension and becomes loose in flexion. Hyperextension of the joint is prevented by the volar plate, with the check-rein ligaments being the major component imparting this stability (► Fig. 62.1).

62.3 Evaluation

The joint needs to be tested in isolation to evaluate all the soft tissue stabilizers, including the collateral ligaments, volar plate, and central slip. Active and passive range of motion should be tested, and the soft tissue structures need to be stressed to evaluate their integrity. Examination of the uninjured side is helpful in assessing the patient’s “normal” degree of laxity and range of motion. If the joint cannot be reduced concentrically, there is likely soft tissue interposed in the joint. This is commonly the lateral band, collateral ligament, or volar plate.

The lateral stress test isolates the collateral ligament. It should be performed in full extension and 30 to 40 degrees of flexion, with the latter isolating the collateral ligaments and removing stability from the secondary stabilizers. Using the tip of a pen or eraser can help isolate the exact location of pain, as the ligaments lie in close proximity to the other soft tissue joint structures. Isolating the exact location of pain can help isolate the exact injured structure. A digital block can help to assess the joint when pain is limiting the examination.

Radiographs assess joint congruency and it is essential to obtain a dedicated true lateral of the joint. A hand X-ray does not suffice. An MRI or ultrasound can be helpful in assessing the ligament but are often unnecessary with good clinical examination. Arthroscopic evaluation of the PIP joint using 1.5 mm or smaller arthroscopes is an evolving technique to fully asses the joint and evaluate for chondral injuries.

The most common injury pattern is an avulsion off the origin site proximally, with the radial side more commonly injured. 3 , 4 Ligament injuries are graded as I, II, or III. Grade I injuries are sprains with stable active and passive range of motion. Grade II injuries are complete disruption of one collateral ligament with stable active range of motion and passive range of motion illustrating instability greater than 20 degrees of angular deviation. 3 Grade III injures involve complete disruption of one collateral ligament and another stabilizing structure (volar plate, central slip, etc), with unstable active and passive range of motion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree