5. Basics of Anesthesia for the Aesthetic Surgery Patient

General Principles

Anesthesia for patients undergoing purely elective aesthetic procedures presents specific challenges that encompass:

Patient selection

Surgical venue selection (ambulatory surgery centers, offices, hospital)

Choice of anesthetic technique(s)

Personnel requirements

Postoperative care and pain management

Discharge criteria

Patient satisfaction

Requires high level of understanding, communication, and cooperation between surgeon and anesthesia provider to ensure optimal surgical outcome and patient experience

Regulatory agencies establish minimum standards of care in aesthetic surgery environments.

Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC)

The Joint Commission (TJC), formerly Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO)

American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF)

Regulations may vary with regard to state and type of facility.

Professional societies provide consensus statements, guidelines, recommendations, practice parameters, and advisories for evidence-based best practices for ambulatory surgery centers (ASC) and office-based practices.

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia (SAMBA)

American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA)

American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)

American College of Surgeons (ACS)

American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS)

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS)

Anesthetic Goals

Anxiolysis

Amnesia

Analgesia

Sedation

Unconsciousness or hypnosis

Immobility, including muscle relaxation or paralysis

Quiet, nondistracting operating milieu, if patient awake

Attenuation of autonomic responses to noxious stimuli

Preservation of vital functions

Objectives of Anesthesia in the Aesthetic Patient

Safe implementation of chosen technique

Fast-track characteristics with rapid onset and emergence

Predictable and reliable methodology

Prevention of undesirable side effects

Confidence in ability to meet accepted discharge criteria

Patient satisfaction commensurate with entirely elective, often self-funded, procedures

Techniques

General Anesthesia

“Balanced” technique incorporates multiple classes of IV drugs (sedative-hypnotics, narcotics, muscle relaxants), along with the volatile/inhalational agents (desflurane, sevoflurane, less commonly isoflurane and nitrous oxide).

Volatile agents

Easier titration of depth, faster emergence, and early recovery

Lesser risk of intraoperative awareness

Simple administration

Typically less expensive maintenance agent

Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA)

Component therapy involving sedative-hypnotic infusion (propofol, ketamine, dexmedetomidine)

Additional drugs such as midazolam, choice of narcotic, or muscle relaxant supplemented either by IV bolus or infusion

Aided by liberal surgical use of local anesthetic block or infiltration

Reduced incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

High degree of patient satisfaction

More complex administration

Increased cost

Avoids gas delivery systems and therefore need for scavenging equipment

Avoids malignant hyperthermia (MH) triggers (see Malignant Hyperthermia section later in the chapter)

Various well-described “recipes” for TIVA 5 , 6 , 8 commonly include:

Propofol: Sedation/hypnosis

Midazolam: Anxiolysis and amnesia

Ketamine: Dissociation and analgesia

Opioids (fentanyl, alfentanil, remifentanil): Analgesia

Rocuronium: Muscle relaxation

Dexmedetomidine: Anxiolysis, sedation, analgesia, decreased adrenergic output

Acetaminophen: Nonopioid analgesic

Ketorolac: NSAID

Frequently accompanied by use of “depth of anesthesia” or “level of consciousness” monitoring

Employs algorithm-driven surface EEG to calculate an “index” number that correlates with hypnotic level

Bispectral Index (BIS; Medtronic) commonly used in the United States

Airway can be natural or controlled (endotracheal tube or supraglottic airway), with either mechanical or spontaneous ventilation.

Regional Anesthesia

Neuraxial (spinal or epidural)

Nerve blocks: Plexus, peripheral, paravertebral, intercostal, specific nerve branch, transversus abdominal plane (TAP), truncal, or other

IV sedation, at multiple and varying levels

Local infiltration

Selection determined by

Type, extent, and duration of surgery

Patient or surgeon preference

Anesthesiologist experience

Patient’s underlying medical status and/or any pertinent psychological aspects

Can be isolated anesthetic technique or involve combinations listed previously

Important Considerations with Administration of Anesthetics

Standard of care for nonhospital locations should be equivalent to those of hospitals.

ASA Standards for Basic Anesthetic Monitoring 10 (last amended 2011) must be met.

Emergency protocols must be established, documented, and rehearsed.

Transfer agreement with nearby/associated hospital for unplanned admission must be established.

Preoperative risk assessment and evaluation are required, including laboratory tests and specialty consultation as needed. 11

Selection of anesthesia type with appropriate monitoring

Selection of appropriate model of provider(s)

Anesthesiologist, alone or as part of anesthesia care team, with certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) or, in some states, an anesthesia assistant (AA)

CRNA supervised by surgeon

Surgeon supervising RN whose sole responsibility is administration of ordered medication(s) and monitoring patient

Appropriate education, training, and certification of staff involved in all phases of patient care

Duration and complexity of procedure(s), especially if multiple procedures will be performed simultaneously or concurrently

Preoperative medications and postoperative pain control plans

Discharge criteria and postoperative follow-up

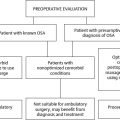

Preoperative Screening, Evaluation, and Patient Selection

Goals

Identify and optimize comorbid conditions.

Assess suitability for ASC or office.

Align anesthetic needs and resources with proposed procedure and patient needs.

Minimize perioperative risk.

Reduce delays and cancellation.

Assess ability for safe and timely discharge.

Provide education and reassurance to patients to build confidence.

Tools

Checklist-format patient questionnaire

Primary care physician/practitioner evaluation

Subspecialty consultations as needed

Old anesthesia records

In-person or phone interview with anesthesiologist or nurse

Video chat, Skype, or telemedicine

Timing

Process guided by

Patient demographics

Patients’ clinical conditions

Invasiveness of procedure

Nature of the health care system

Can be done day of surgery (DOS) if low severity of disease and procedure of low-medium surgical invasiveness, otherwise in advance

Things Anesthesiologists Like To Know Or Review

Up-to-date history and physical examination

Pertinent active medical conditions

Current medications and therapies in place

Status of optimization of current problems

Pertinent subspecialty consultation

Pertinent diagnostic studies of record

Pertinent psychosocial conditions

Surgical findings and operative plan

History of difficult intubation

History of PONV or postdischarge nausea and vomiting (PDNV) (discussed later in the chapter)

History of other anesthetic complications like delayed emergence, unanticipated admission, or prolonged postanesthesia care unit (PACU) stay

Personal or familial history suggestive of malignant hyperthermia

Intangibles, nuances, or needs that may affect patient’s satisfaction or experience in this highly specialized, consumer-driven patient population

Identifying Risk Factors

Red flags of unsuitability for general anesthesia in an ASC or office 2 , 5 , 9 , 12

Unstable angina

Myocardial injury within 3–6 months

Severe cardiomyopathy

Uncompensated heart failure

Aortic stenosis (moderate to severe) or symptomatic mitral stenosis

Uncontrolled or poorly controlled hypertension

High-grade arrhythmias

Implantable cardiac devices (pacer-dependent or defibrillator)

Recent stroke within 3 months

End-stage renal disease (ESRD)/dialysis

Severe liver disease

Awaiting major organ transplant

Sickle cell anemia

Symptomatic or active multiple sclerosis

Myasthenia gravis

Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Abnormal/difficult airway

Severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

Morbid obesity

Psychiatric status unstable, dementia

Acute substance intoxication

Poor functional status <4 metabolic equivalents (METs) (discussed later in the chapter)

Mathis et al 15 (2013) suggested seven independent risk factors associated with increased 72-hour morbidity and mortality in ambulatory surgery:

Overweight BMI

Obese BMI

COPD

History of transient ischemic attack/stroke

Hypertension

Previous cardiac surgical intervention

Prolonged operative time

Preoperative Testing

The culture shift is to NO routine testing.

Tests should be for indication only, as per current medical conditions or per procedure.

Avoid baseline laboratory studies when:

Patient is healthy

Patient has less than significant systemic disease (ASA I or II)

Blood loss expected to be minimal

Procedure is designated low risk

Testing guidelines available from ASA, SAMBA, ACC/AHA

Pregnancy (Hcg) Test

Positive pregnancy tests have been reported in 0.3%–1.3% of premenopausal menstruating females, which led to postponement, cancellation, or changes in management of 100% of the cases. 14

Routine testing of all females within childbearing years remains controversial.

Evidence-based medicine is inadequate or unsupportive with regards to anesthetic exposure and teratogenic effects or other harmful effects, e.g., spontaneous abortion, stimulation of contractions, or premature birth.

ASA provides no consensus on routine testing versus based on clinical menstrual history.

Recommends “offering” rather than “requiring” hCG testing

Affords “individual physicians and hospitals the opportunity to set their own practices and policies” according to ASA Choosing Wisely initiative 16

Many institutions perform routine point of care (POC) urine hCG on day of surgery.

Some institutions perform rapid qualitative serum hCG testing should urine results be equivocal or contested by patient.

Hemoglobin / Hematocrit (Hgb /Hct) and Complete Blood Cell Count (CBC)

Significant blood loss anticipated (>500 ml)

Patients with liver disease

Extremes of age

Preexisting anemia

Hematologic disorders

Factor deficiencies

Chemistries

High-grade dysrhythmia, pacemaker, cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED), e.g., defibrillator

H/O heart failure

Diabetes

Chronic renal insufficiency (CRI) or ESRD

Hepatic disease

Poorly controlled hypertension

Malabsorption/malnutrition (note history of eating disorder or bariatric surgery)

Blood Glucose

In diabetics, obtain by blood draw as preadmission testing (PAT) or by point of care testing on day of surgery

HbA1C is helpful in perioperative glucose interpretation and management

Coagulation Studies (PT, PTT, INR)

Bleeding disorders

Liver disease

Factor deficiencies

Chemotherapy

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Box 5-1% When to Obtain a Preoperative Electrocardiogram

Patient with known CAD or risk factors

Patient for high risk (>1%) surgery

Patient with known arrhythmias (helpful to have a baseline)

Patient with known peripheral or cerebral vascular disease

Patient with significant structural heart disease

Patient with signs or symptoms of active cardiac conditions, e.g., chest pain, diaphoresis, shortness of breath (SOB), dyspnea on exertion (DOE)

Patient with DM requiring insulin or end-organ damage

Patient with renal insufficiency

Based on cardiac risk

Not indicated for asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk surgery, regardless of age (ACC/AHA 2014)

Moderate-risk cosmetic procedures (abdominoplasty, large-volume liposuction, or body contouring after massive weight loss) with at least one clinical risk factor supports obtaining baseline or current/updated ECG.

ECGs valid for 6 months, if patient clinically stable

Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) clinical risk factors:

Coronary artery disease (CAD) with H/O myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) bypass, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), intracoronary stents

Cerebral vascular disease, with H/O stroke or transient ischemic events

Heart failure

Diabetes, requiring insulin, poorly controlled, or with end-organ damage

Renal insufficiency, serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dl or ESRD

RCRI stratifies risk of major cardiac complications.

No risk factors: 0.4%

One risk factor: 1.0%

Two risk factors: 2.4%

Three or more risk factors: 5.4%

Risk interpreted as:

Patients with <1.0% are low risk and need no further testing.

Patients with ≥1.0% are a greater risk and should be evaluated for optimization or further workup before elective surgery.

High-risk indicators that should command attention and dissuade from elective surgery in anything but a hospital setting, or not at all, are:

Recent MI

Unstable angina

Uncompensated heart failure

High-grade arrhythmias

Hemodynamically significant valvular disease, e.g., aortic stenosis

Additional considerations used as risk factors

Morbid obesity

Poorly controlled hypertension

High-grade arrhythmia, pacemaker, or implanted defibrillators

H/O significant peripheral arterial disease

Chest Radiograph

Not many indications in the elective aesthetic surgery patients

Active symptomatic pulmonary disease

Advanced Cardiovascular Testing

Stress test, ECG, carotid duplex, vascular studies guided by subspecialty consultation

Asa Physical Status Classification (ASA PS)

Used as a global descriptor of a patient’s clinical state based on history, physical examination, and laboratory data

Most widely used and accepted method of describing preoperative health status

Gross predictor of overall risk; does not assess surgical risk per se 9

Robust predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality

Validated by and incorporated in current risk assessment models 18

Other applications include allocation of resources and anesthesia reimbursement. 19

Limitations include subjectivity and interrater inconsistency. 18

Recently updated by ASA 2014

Definitions remain unchanged, but clinical examples reflect liberalization with some stable chronic severe diseases, e.g., ESRD with hemodialysis, moving from class IV to class III

Patients frequently present for aesthetic surgery with multiple medical problems that represent an ASA III status.

ASA III patients are a widely disparate group with huge variations in pathophysiology.

Note:

The presence of stable, optimized preexisting diseases consistent with an ASA III status is NOT a contraindication for elective surgery

NPO Fasting Guidelines and Prevention of Pulmonary aspiration

Fasting

Ingested Material | Minimum Fasting Period (hours) |

Clear liquids | 2 |

Dairy, nonclear juices | 6 |

Light meal (toast and clear liquid) | 6 |

Heavy meal (fried, fatty foods; meat) | ≥8 |

Guidelines are limited to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures.

Modification based on clinical indicators may be needed.

Modification may be needed if difficult airway is anticipated.

Patients need to be informed (verbal, written) and status verified on day of surgery.

Following the guidelines does not guarantee sufficient gastric emptying.

Note:

Allowing black coffee and plain tea as “clear liquid” intake per guidelines for healthy patients without aspiration concerns can have added benefit of preventing caffeine withdrawal headaches

Acid Aspiration Prophylaxis and Considerations

Pulmonary aspiration: Aspiration of gastric contents occurring after the induction of general anesthesia, during a procedure, or in the immediate period after surgery

ASA and SAMBA recommend NO ROUTINE administration of preoperative acid aspiration prophylaxis medications.

Clinical indications for use of medications, AS WELL AS EXTENDING OR MODIFYING NPO GUIDELINES, incorporate comorbidities that affect or delay gastric emptying:

Obesity

Pregnancy

Diabetes

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Hiatal hernia

After bariatric surgery (especially laparotomy band)

Ileus or bowel obstruction

Emergency surgery (e.g., return to OR for hematoma or wound dehiscence after PO intake in PACU)

Preoperative prophylactic medications include:

Gastrointestinal stimulants (metoclopramide)

Gastric acid blockers

H2-receptor antagonists (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine)

Proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, lansoprazole)

Antacid, nonparticulate (sodium citrate)

Antiemetics (ondansetron, prochlorperazine) used alone or in combination

Functional Status and Metabolic Equivalents (METS)

Functional Status Or Functional Capacity

Derived by estimating patient’s abilities to perform various tasks and activities of daily living (ADLs)

Expressed in METs

1 MET = 3.5 ml O2 uptake/kg/min (resting oxygen uptake in sitting position)

Adjunct to assess cardiac risk

Although not a formal component of the ASAPS classification, it is part of the routine anesthetic preoperative evaluation described as:

<4 METs; = 4 METs; <4 METs

Used as an indicator on Gupta Myocardial Infarction and Cardiac Arrest (MICA) Perioperative Cardiac Risk Calculator 22

Used as an indicator on ASC National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator 11

Has been suggested as a useful adjunct in assessing ASA class II-IV patients and an independent predictor of outcome and mortality 23

Patient descriptors:

Totally independent

Partially dependent

Totally dependent

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree