Fig. 45.2 Euphorbia lathyrus, the caper spurge (so-called because the seed capsules resemble caper buds). Injury to the plant releases irritant milky sap.

The term ‘urticaria’ is derived from species of Urtica, the stinging nettle (Fig. 45.3). This, in common with several other related species, possesses sharp hairs (emergences) on the surface of the leaves and stem. After minor trauma, such as brushing against the plant, a mixture of inflammatory mediators, including histamine and acetylcholine [10], is injected into the skin. This is followed by numbness and tingling at the site, doubtless due to a neurotoxin that is as yet unidentified [11], although oxalic acid and tartaric acid may contribute to prolonged pain following nettle stings [12]. A persistent, urticated eruption was described in a 9-year-old child who fell into a bush of Urtica urens. The authors suggest there may be an element of an immediate and delayed hypersensitivity, presumably in addition to the chemical irritation [13]. Another possible explanation could be delayed release of urticating material into the skin. Attacks are usually minor, although tropical urticant species such as Dendrocnide (Fig. 45.4), the stinging tree, native to Australasia, have caused death to humans and browsing animals [14].

Fig. 45.4 Dendrocnide excelsa, a small plant with characteristic raspberry-like fruit.

Photographed in cultivation (with appropriate warning) at Oxford Botanic Garden.

References

1 Lovell CR. Irritant plants. In: van der Valk PGM, Maibach HI (eds) The Irritant Contact Dermatitis Syndrome. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1995.

2 Grange FM, Noble WC, Yates MD et al. Inoculation mycobacterioses. Clin Exp Dermatol 1988;13:211–20.

3 Putman MH. Simple cactus spine removal. J Pediatr 1981;98:333.

4 Commens C, McGeoch AH, Bartlett B et al. Bindii (jo-jo) dermatitis [Soliva pterosperma (Compositae)]. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:768–73.

5 Neri I, Bianchi F, Giacomini F et al. Acute irritant dermatitis due to Juglans regia. Contact Dermatitis 2006;55:62–3.

6 Franceschi VR, Herner HT. Calcium oxalate crystals in plants. Bot Rev 1980;46:361–426.

7 Pohl RW. Poisoning by Dieffenbachia. JAMA 1961;177:812–13.

8 Spoerke DG, Temple AR. Dermatitis after exposure to a garden plant (Euphorbia myrsinites). Am J Dis Child 1979;133:28–9.

9 Pinedo JM, Saavedra V, Conzales D et al. Irritant dermatitis due to Euphorbia marginata. Contact Dermatitis 1985;13:44.

10 Kulze A, Greaves M. Contact urticaria caused by stinging nettles. Br J Dermatol 1998;119:269–70.

11 Oliver F, Amon EU, Breathnach A et al. Contact urticaria due to the common stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) – histological, ultra-structural and pharmacological studies. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991;16:1–17.

12 Fu HY, Chen SJ, Chen RF et al. Identification of oxalic acid and tartaric acid as major persistent pain-inducing toxins in the stinging hairs of the nettle Urtica thunbergiana. Ann Bot (Lond) 2006;98:57–65.

13 Edwards EK Jr, Edwards EK Sr. Immediate and delayed hypersensitivity to the nettle plant. Contact Dermatitis 1992;27:264–5.

14 Winkler H. Die Urticaceen Papuasiens. Bot Jahrb 1922;57:501–8.

Allergy and Hypersensitivity to Plants or Plant Products

Urticaria and Angio-Oedema

Immediate (type 1) hypersensitivity is a potentially serious problem in children. There is a strong association with atopy. These individuals may mount a type 1 allergic reaction to a variety of different naturally derived proteins (Table 45.3), including foodstuffs such as peanuts, cashew nuts [1] and fruit (e.g. kiwi fruit and banana [2]), airborne pollens (e.g. mulberry [3]) and grasses [4].

Table 45.3 Immunological urticaria due to plants or plant products

| Vegetables | Beans, tomatoes |

| Fruits | Apple, banana, kiwi fruit, strawberry |

| Nuts | Almond, brazil, peanut |

| Spices | Cinnamon, caraway |

| Essential oils | Sesame seed oil |

| Cosmetic ingredients | Balsam of Peru, lime extract |

| Rubber latex protein |

Occasionally, children may become sensitized to plant products used in medicaments. An example is radish, Raphanus niger [5]. Recently, type 1 hypersensitivity to rubber proteins has become increasingly important. Rubber is derived from the tree Hevea brasiliensis. The antigens are water-soluble proteins on the surface of finished products, such as rubber gloves, balloons, teats and pacifiers [6]. Fatal anaphylaxis has followed the use of rubber catheters for barium enemas in children with spina bifida [7]. Latex-sensitive individuals may exhibit cross-sensitivity to fruits such as apples and bananas [8].

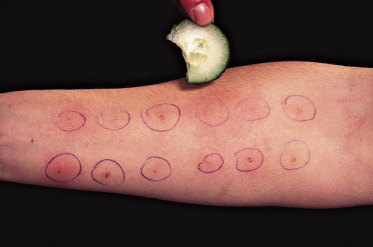

Investigation can be difficult. In the skin application food test (SAFT), the suspected material is applied to an area of skin that has been cleansed of fat with 96% alcohol. The allergen is covered with a piece of gauze and then fixed with Finn chamber plasters (Scanpor, Bard, Covington, GA). The patches are examined at 10-min intervals for up to 30 min. A positive reaction is regarded as erythema and oedema rather than erythema alone. This technique is reported to be suitable in small children with atopic dermatitis, although it diminishes in older children aged 4 years or more [9]. Patch testing to members of the grass family (Gramineae) appears to correlate well with prick testing or a specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) measured by radio-allergosorbent test (RAST) [10]. In the older child, prick testing may be the preferred technique (Fig. 45.5). A sliver of the material is placed on the flexor forearm and a blood lancet or sterile hypodermic needle, bevel upwards, is inserted through the material almost parallel with the skin, barely tenting up the epidermis, and taking care not to draw blood. The material is then secured in place with tape and left for 15–20 min. More positive reactions are obtained using the scratch chamber method, in which the test material is occluded with an aluminium patch test chamber. After reading, the chamber can be replaced to test for delayed hypersensitivity [11]. Scratch testing and intradermal testing are more hazardous than prick testing, particularly with rubber latex [12]. These procedures should only be performed when adequate resuscitation facilities are available.

Ideally, management consists of avoiding the offending antigen. A selective H1-antagonist, such as chlorpheniramine, particularly in syrup form, is helpful for the treatment of an acute allergic reaction. In children with allergy to common foodstuffs such as peanuts, there is sometimes a case for the use of a preloaded adrenaline syringe if there is any risk of anaphylaxis. Several allergens in fruit or vegetables, e.g. apples, are destroyed by cooking or processing [13].

References

1 Davoren M, Peake J. Cashew nut allergy is associated with a high risk of anaphylaxis. Ann Dis Child 2005;90:1084–5.

2 Linaweaver WF, Saks GL, Heiner DC. Anaphylactic shock following banana ingestion. Am J Dis Child 1976;130:207–9.

3 Muñoz FJ, Delgado J, Palma MJ et al. Airborne contact urticaria due to mulberry (Morus alba) pollen. Contact Dermatitis 1995;32:61.

4 Desager K, van Bever HP, Stevens WJ. Contact sensitivity to aeroallergens in children with atopic dermatitis (AD) demonstrated by patch test. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1987;79:236.

5 El Sayed F, Manzur F, Marguery MC et al. Urticarial manifestations due to Raphanus niger. Contact Dermatitis 1995;32:241.

6 Kimata H. Latex allergy in infants younger than 1 year. Clin Exp Allergy 2004;34:1910–15.

7 Monoret-Vauerin DA, Mata F, Gueant JL et al. High risk of anaphylactic shock during surgery for spina bifida. Lancet 1990;335:865–6.

8 Dompmartin A, Szczurko C, Michel M et al. Two cases of urticaria following fruit ingestion, with cross-sensitivity to latex. Contact Dermatitis 1994;30:250–2.

9 Oranje AP, van Gysel D, Mulder PGH et al. Food-induced contact urticaria syndrome (CUS) in atopic dermatitis: reproducibility of repeated and duplicate testing with a skin provocation test, the skin application food test (SAFT). Contact Dermatitis 1994;31:314–18.

10 Seidenari S, Manzini BM, Danese P. Patch testing with pollens of Gramineae in patients with atopic dermatitis and mucosal atopy. Contact Dermatitis 1992;27:125–6.

11 Niinimaki A. Scratch-chamber tests in food handler dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 1987;16:11–20.

12 Turjanmaa K, Reunala T. Contact urticaria from rubber gloves. Dermatol Clin 1988;6:47–51.

13 Bjorksten F, Halmepuro L, Hannuksela M et al. Extraction and properties of apple allergens. Allergy 1980;35:671–7.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis: Delayed Hypersensitivity

Allergic contact dermatitis in children is covered more fully in Chapter 44. In recent surveys of patch testing in children [1–4], reactions to plants or plant products are described rarely, if at all. For example, in a large Italian survey [3], only one positive reaction to primin was reported in 323 children with dermatitis and inflammatory psoriasis. Plants reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis in children are listed in Table 45.4.

Table 45.4 Plants and plant products reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis in children

| Family | Genus/species |

| Anacardiaceae | Rhus (including Toxicodendron): poison ivy, oak and sumac, Japanese lacquer tree. Sensitization to poison sumac has been reported in newborn infants [5] |

| Anacardium occidentale: cashew nut tree [8] | |

| Smodingium argutum: African poison ivy [9] | |

| Leguminosae | Myroxolon pereirae: balsam of Peru, a sticky gum derived from the trunk, is an important sensitizer in children [10] |

| Araliaceae | Hedera helix: ivy. Sensitizes children who climb walls/trees [11] |

| Compositae (Asteraceae) | Dahlia cultivars: dermatitis of the face and hands reported in a gardener’s boy [12]. Inula britannica: contaminated hay [13] |

| Styraceae | Styrax tonkinensis: source of Siam benzoin, an ingredient of compound tincture of benzoin, still applied under plaster casts and other dressings used in children and adults [14] |

| Dioscoraceae | Dioscorea batatas: yam. A 9-year-old girl developed dermatitis after being accidentally hit on the cheek with a spoon containing grated yam [15] |

| Gramineae | Arundo donax

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|