Fig. 28.3 Symmetrical eczema involving the trunk and extensor surfaces in infantile atopic dermatitis.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

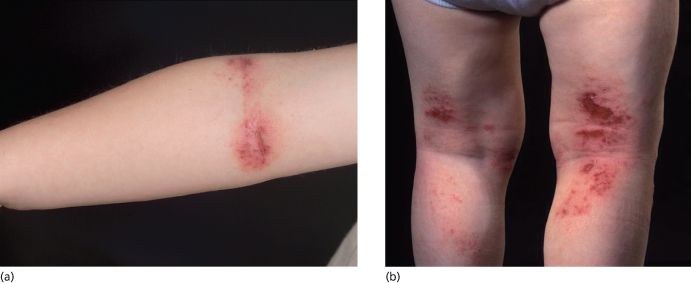

In childhood, AD distribution changes from an extensor to a flexural pattern at around 2–3 years of age. The tendency for skin inflammation and the effects of chronic rubbing (lichenification) to become accentuated in the flexures is one of the classical hallmarks of AD (Fig. 28.4) [3]. Flexures refer to bends in the articular skeleton where skin apposes skin. What exactly constitutes a flexure varies from text to text, but most agree that the fronts of the elbows, backs of the knees, around the neck and in front of the ankles are the commonly affected flexures. All of the flexure is not always involved – lichenification as a result of prolonged rubbing typically occurs most prominently behind the knees along the most prominent tendons (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) and likewise overlying the brachioradialis muscle group on the antecubital fossae (Fig. 28.5a,b).

Fig. 28.4 Thickened lichenified atopic dermatitis on the lower leg and dorsal foot in darkly pigmented skin.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

Fig. 28.5 (a,b) Flexural subacute atopic dermatitis involving the antecubital and popliteal fossae with erythema and excoriations.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

Other less commonly affected areas include the wrists and folds beneath the buttocks (infragluteal folds). Why the axillae are infrequently involved is unclear, and the presence of axillary involvement may be a marker of seborrhoeic as opposed to atopic dermatitis. Two points are worthy of note with regards to flexural involvement; the first is that AD can affect any part of the body. The fact that a child presents with an itchy scalp and diffuse patches of skin inflammation on extensor parts of the limbs should not put one off diagnosing AD since it is the most common inflamed itchy chronic skin eruption in developed countries.

From puberty onwards, AD tends to affect the face, hands, back, wrists and dorsal feet. The hands and fingers are frequently involved probably as a result of constant irritant exposure, which may result in fissures overlying the finger joints (Fig. 28.6) and scaling on the palms adjoining the fingers (apron sign). Adults may only have persisting hand eczema and skin that is sensitive to irritant exposure, or they may have persistent chronic AD.

Fig. 28.6 Chronic hand eczema with loss of cuticles, nail dystrophy, fissuring and scaling.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Specific sites that are frequently involved by AD are as follows: lips with cheilitis in childhood (Fig. 28.7), which can lead to secondary ‘lip-lick cheilitis’ or exfoliating cheilitis with perlèche (single or multiple fissures and cracks at the labial commissures) and involvement of the vermillion border in adult AD. The retroauricular region is frequently affected by fissures (rhagades) in children (Fig. 28.8) while eyelids are frequently involved in adolescents and adults. Nipple eczema is frequently seen from puberty onwards (Fig. 28.9). Some sites of predilection of AD such as around the eyes, mouth or nose (Fig. 28.10) or under the ear also occur probably as a result of influences other than skin-to-skin contact such as airborne allergens and irritants, or irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth from saliva and wet foods in early age.

Fig. 28.7 Acute cheilitis in a child with atopic dermatitis with erythema and swelling of the vermillion border and perioral region and fissuring of the commissures.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Fig. 28.8 Rhagades of the infra-auricular region in childhood atopic dermatitis.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Fig. 28.9 Acute nipple eczema with erythema, erosions, oozing and secondary impetiginization.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Fig. 28.10 Subacute eczema with fissuring and oedema.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Configuration

In addition to the distributions described, AD can occasionally demonstrate a Koebner phenomenon, whereby new lesions develop at the site of skin injury.

Morphology

The morphology of AD can be variable and depends on the stage of the lesion. Acute lesions are characterized by ill-defined erythema, papules, papulovesicles, erosions and weeping (Fig. 28.11a). Subacute lesions are erythematous scaly excoriated plaques and papules (Fig. 28.11b) while thickened purple/grey lichenified plaques and fibrotic papules (prurigo) are seen in chronic lesions (Fig. 28.11c). During infancy, AD tends to be acute and exudative with chronic forms of AD developing later in childhood. In longstanding AD, individuals may manifest all three stages of AD concurrently or at different times depending on the level of disease activity, reflecting the relapsing and remitting nature of eczema.

Associated Physical Signs

A number of clinical signs frequently accompany AD and may be clues to the diagnosis when the distribution and morphology are not classical, although they may not be pathognomonic of AD. A number of these will be briefly discussed here.

Periocular and Ocular Signs

Infraorbital folds (Dennie–Morgan lines) are frequently seen in AD, with most studies reporting their presence in 50–60% of cases of AD. However, this sign appears to vary depending on ethnicity and shows significant variability even within individuals (Fig. 28.12). Periorbital pigmentation, ‘atopic shiners’, describes a periorbital brown to grey discoloration [4]. As previously discussed, thinning or absence of the outer eyebrows (Hertoghe’s sign), a sign originally described in hypothyroidism, may also be seen although its prevalence has not been extensively studied (Fig. 28.13). Specific ocular signs such as keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus and anterior subcapsular cataracts may be associated with AD although their population-based frequency is difficult to identify from the literature.

Fig. 28.12 Symmetrical infraorbital Morgan–Dennie folds.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Fig. 28.13 Thinning of the outer eyebrows (Hertoghe’s sign) with extensive scaling and lichenification of the forehead.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Other Cutaneous ‘Minor’ Signs

Two features are described in the neck region, namely the anterior neck folds and atopic ‘dirty neck’ (Fig. 28.14). The ‘dirty neck’ refers to rippled hyperpigmentation of the anterior and lateral neck, which clinically resembles macular amyloid. Facial pallor and white dermographism (blanching of the skin at the site of stroking with a blunt instrument rather than developing a partial or full triple response of Lewis with reflex erythema), are frequently described in AD and are thought to represent abnormal vascular responses (Fig. 28.15).

Fig. 28.14 Rippled hyperpigmentation of the lateral neck (atopic ‘dirty neck’).

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Fig. 28.15 White dermographism with blanching of the skin at the site of stroking with a blunt instrument rather than developing a partial or full triple response of Lewis with reflex erythema.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Dry skin (xerosis) is seen in all age groups with AD and is considered a hallmark of AD (Fig. 28.16). This is characterized by fine scaling without associated inflammation and roughness on palpation. Dry skin may be associated with ichthyosis vulgaris, an autosomal dominant condition seen in 8% of individuals with AD [5,6]. However, studies show that dry skin is also independently associated with AD in the absence of icthyosis vulgaris [7]. Hyperlinear palms are a frequent finding in AD (Fig. 28.17). Recent studies have shown that palmar hyperlinearity is more frequently seen in AD compared to atopiform dermatitis (AD without raised IgE levels) and that this sign is strongly associated with filaggrin null mutations and ichthyosis vulgaris [8,9].

Fig. 28.17 Hyperlinear palms with exaggerated wrinkling of the palms.

Courtesy of Professor Alan Irvine.

Pityriasis alba describes a condition frequently associated with AD characterized by poorly defined slightly scaly hypopigmented patches on the cheeks and upper arms (Fig. 28.18). This clinical sign is more obvious in dark skin and can be mistaken for tinea corporis.

Fig. 28.18 Pityriasis alba with poorly defined slightly scaly hypopigmented patches on the torso, arms and cheeks.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Atopic Dermatitis in Dark Skin Types

The diagnosis of eczema in dark skins is complicated by the lack of visible erythema. The diagnosis is made based on the presence of a typical history accompanied by lesions demonstrating a distribution and morphology consistent with AD. Other features classically seen in African skin are enhanced follicular lichenification with a papular appearance and postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation (Fig. 28.19).

Fig. 28.19 Postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation in darkly pigmented skin.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

Clinical Features of Specific Subtypes of Atopic Dermatitis

Specific subtypes of childhood AD deserve a mention as their morphology and distribution have not been previously discussed in this chapter.

Nummular or Discoid Atopic Dermatitis

This type of AD presents with sharply demarcated circular lesions (Fig. 28.20) often located on the trunk and distal extensor limbs including dorsal hands, lower legs and forearms. The individual lesions are frequently dry and infiltrated plaques. This type of AD is reported to worsen in winter time. In adults, nummular eczema may be independent of atopy.

Fig. 28.20 Nummular atopic dermatitis affecting the torso in a young child.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

Diffuse ‘Dry Type’ AD

This type of AD was first described in Japan and refers to a diffuse dry type AD, sometimes called patchy pityriasiform lichenoid eczema, which is slightly irritating and clinically consists of confluent scaly non-hyperkeratotic skin-coloured papules or ‘chicken-skin spots’ mainly on the trunk region [10]. Seasonal variations are described, with worsening in winter.

Possible Future Subtypes

Recent advances in our understanding of the genetic basis for AD are likely to lead to new subtypes of AD. Specific emerging subtypes include eczema associated with null filaggrin mutations. These mutations appear to be associated with severe early-onset extrinsic (elevated IgE levels) eczema with palmar hyperlinearity and keratosis pilaris [11]. Recent studies of asthma in the context of filaggrin mutations have identified a complex asthma and eczema phenotype whereby filaggrin mutations are associated with asthma but only when it is associated with AD [12].

Complications

Bacterial Infections

Staphylococcus aureus colonization can be demonstrated in 90% of eczema lesions and its density is associated with disease severity [13]. Clinically infected AD is characterized by honey-coloured crusted impetigo, folliculitis and pyoderma or as worsening of AD with increased erythema, oozing and pain (Fig. 28.21). Infections are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus but β-haemolytic streptococci may also be isolated from infected AD.

Fig. 28.21 Clinically infected infantile atopic dermatitis affecting the extensor aspects of the limbs and trunk.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams

Viral Infections

Infections with herpes simplex virus (HSV) in individuals with AD can result in eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This is a serious but infrequent complication, occurring in 3% of AD patients characterized by disseminated HSV infections and associated with significant morbidity, including multiorgan involvement, and rarely mortality. Clinically this presents with grouped or widespread umbilicated vesicopustules and eroded vesicles (Fig. 28.22). This complication is usually secondary to HSV-1 infection and recent studies suggest that there may be an association with filaggrin mutations [14]. A clinically similar eruption (eczema vaccinatum) can be seen following smallpox vaccination in susceptible individuals, hence AD or household AD contacts is a contraindication for smallpox vaccination.

Fig. 28.22 Periorbital eczema herpeticum displaying grouped punched-out erosions with secondary impetiginization.

Courtesy of Professor Hywel C. Williams.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a common childhood cutaneous poxvirus infection that presents with single or grouped skin-coloured papules and is frequently seen in children with AD (Fig. 28.23). Studies have reported an increased incidence of MC with AD, with a recent cross-sectional study showing that 24% of children with MC from a tertiary centre had AD [15].

Fig. 28.23 Molluscum contagiosum presenting as infraorbital umbilicated and crusted papules.

Courtesy of Professor Dr Thomas Diepgen and Dermis.net.

Exfoliative Dermatitis

Exfoliative dermatitis is a life-threatening dermatosis that rarely develops in AD (<1% of cases). In this condition, intense erythema and peeling of more than 90% of the skin surface is accompanied by fever, systemic malaise and lymphadenopathy. This usually develops secondary to either a bacterial infection (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) or eczema herpeticum.

Differential Diagnosis

While AD is one of the commonest causes of an itchy rash in childhood, and in the vast majority of individuals the diagnosis is straightforward, it is important to consider other differential diagnoses. Table 28.1 lists diagnoses that can present in a similar manner to AD. A specific situation in which other differential diagnoses should be considered is when infants present with a severe eczematous rash with failure to thrive, recurrent infections or petechiae [16]. In this scenario, it is important to exclude immunodeficiency states. In children from the Caribbean, severe infected AD may be a manifestation of human T-lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV1) infection [17].

Table 28.1 Differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD)

| Other forms of dermatitis | |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis of infancy | Red, shiny, relatively well-demarcated eruption typically involving nappy (diaper) area in first 4 months of life. Lower abdomen and armpits may also be involved, along with scalp scaling (cradle cap). Non-itchy – child happy but parents are not. Good prognosis – clears within a few months |

| Adult-type seborrhoeic dermatitis | Poorly defined erythema due to overgrowth/sensitivity to Pityrosporum yeasts in seborrhoeic areas, i.e. sides of nose, eyebrows, external ear canal, scalp, front of chest, axillae and groin creases |

| Discoid (nummular) eczema | Circular ‘cracked’ areas of erythema, 1–5 cm in diameter, on limbs initially, often with secondary infection (Fig. 28.1b). In children, most commonly associated with AD, and often confused with tinea (ringworm). In adults may be associated with Staph. infection and excessive skin dryness |

| Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) | Cumulative damage to the skin barrier from irritants such as soaps and detergents. Clinical appearance of dermatitis can be identical to atopic dermatitis, but location at sites of maximal exposure, e.g. fingers, may be helpful. Some degree of ICD is common in atopic dermatitis sufferers, e.g. around mouth in babies due to constant saliva and wet food, and in nappy area due to urine |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | A hypersensitivity reaction to specific substances to which individuals have been sensitized, such as nickel (jewellery), rubber (gloves) or glues (some shoes). Linear cut-off and distribution may suggest diagnosis, but patch tests are needed to establish diagnosis. May coexist with AD |

| Frictional lichenoid dermatitis | Shiny papules occurring in sites of repeated frictional trauma such as outer forearms in children. Probably quite common |

| Hyper IgE syndrome | Features of AD within a few weeks of birth accompanied by staphylococcal infections of the skin, sinuses and lungs, characteristic facies and abnormal dentition. Laboratory findings include high IgE and eosinophils |

| Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome | The rash of Wiskott–Aldrich is identical to AD. It occurs in usually male infants in the first month of life and is accompanied by petechiae, purpura and bloody diarrhoea |

| Other exogenous skin conditions | |

| Scabies | May produce non-specific eczematous changes on the entire body. Burrows and pustules on palms, soles, genitalia and between fingers help to establish diagnosis |

| Onchocercarial dermatitis | In its chronic phase, may produce a widespread lichenification of the skin similar to that seen in chronic AD |

| Insect bites | May often develop secondary eczematization and be confused with AD, especially on the limbs of children in tropical countries |

Summary

- Although atopic dermatitis can affect any part of the body, it has a predilection for the skin folds, the reason for which is still unclear.

- The distribution of eczema changes from involvement of the face, scalp and extensor surfaces in infancy to flexural involvement in childhood and later life.

- The morphological appearance of atopic dermatitis can vary greatly from acute red vesicular eczema to chronic thickened purple/grey lichenified patches.

- Atopic dermatitis can be associated with serious complications including secondary infections and exfoliative dermatitis.

- Other differential diagnoses should be considered when infants present with a severe eczematous rash with failure to thrive, recurrent infections or petechiae.

References

1 Taïeb AWD, Tilles G. The history of atopic eczema/dermatitis. In: Ring JPB, Ruzicka T (eds) Handbook of Atopic Eczema. Berlin: Springer, 2006;10–20.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree