These refined criteria are easy to use and are applicable to a wide range of age and ethnic groups. Nineteen validation studies of the UK diagnostic criteria in both hospital and community populations in a number of different geographical settings, including Romania [14], China [15] and Brazil [16], have found a sensitivity ranging between 10% and 100% and a specificity between 89% and 99% [17]. The UK diagnostic criteria may be a useful step forward in standardizing the definition of AD in epidemiological studies, and they have been widely taken up by international studies that seek to compare the prevalence of allergic disease between countries [18]. Where translation issues become a problem, simply recording the physical sign of visible flexural dermatitis may be the only objective way forward to compare point prevalences between populations [13,19–21].

References

1 Williams HC. Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: where do we go from here? Arch Dermatol 1999;135:583–6.

2 Schultz Larsen F, Hanifin JM. Secular changes in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1992;176 (suppl):7–12.

3 Flohr C, Johansson SGO, Wahlgren CF et al. Association between severity of atopic eczema and degree of sensitization to aeroallergens in schoolchildren. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;114:150–8.

4 Flohr C, Weiland SK, Weinmayr G et al. The role of atopic sensitization in flexural eczema: findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Two. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:141–7.

5 Stranegård Ö, Stranegård I-L. T lymphocyte numbers and function in human IgE-mediated allergy. Immunol Rev 1978;41:149–70.

6 Uehara M, Sawai T. A longitudinal study of contact sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:366–8.

7 Williams HC. What is atopic dermatitis and how should it be defined in epidemiological studies? In: Williams HC (ed) Atopic Dermatitis. The Epidemiology, Causes and Prevention of Atopic Eczema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 3–24.

8 Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic eczema. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1980;92:44–7.

9 Schultz Larsen F. The epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. In: Burr ML (ed) Epidemiology of Clinical Allergy. Basle: Karger, 1993: 9–28.

10 Svensson Å, Edman B, Möller H. A diagnostic tool for atopic dermatitis based on clinical criteria. Acta Dermatol Venereol 1985;114(suppl): 33–40.

11 Diepgen TL, Sauerbrei W, Fartasch M. Evaluation and validation of diagnostic models of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 1994;102:619.

12 Williams HC, Burney PGJ, Pembroke AC et al. The UK working party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol 1994;131: 406–16.

13 Williams HC, Forsdyke H, Boodoo G et al. A protocol for recording the sign of visible flexural dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:941–9.

14 Popescu CM, Popescu R, Williams H et al. Community validation of the United Kingdom diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis in Romanian schoolchildren. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:436–42.

15 Gu H, Chen XS, Chen K et al. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: validity of the criteria of Williams et al. in a hospital setting. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:428–33.

16 Yamada E, Vanna AT, Naspitz CK et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): validation of the written questionnaire (eczema component) and prevalence of atopic eczema among Brazilian children. J Invest Allergol Clin Immunol 2002;12(1):34–41.

17 Brenninkmeijer EE, Schram ME, Leeflang MM, Bos JD, Spuls PI. Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2008;158:754–65.

18 Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:125–38.

19 Flohr C, Weinmayr G, Weiland SK et al. How well do questionnaires perform compared to physical examination in detecting flexural eczema? Findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Two. Br J Dermatol 2009;161(4):846–53.

20 Chalmers DA, Todd G, Saxe N et al. Validation of the United Kingdom Working Party Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Eczema in an African setting. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:111–16.

21 Ellwood P, Williams H, Aït-Khaled N et al. Translation of questions: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13(9):1174–82.

Descriptive Epidemiology of Atopic Dermatitis

Prevalence and Incidence

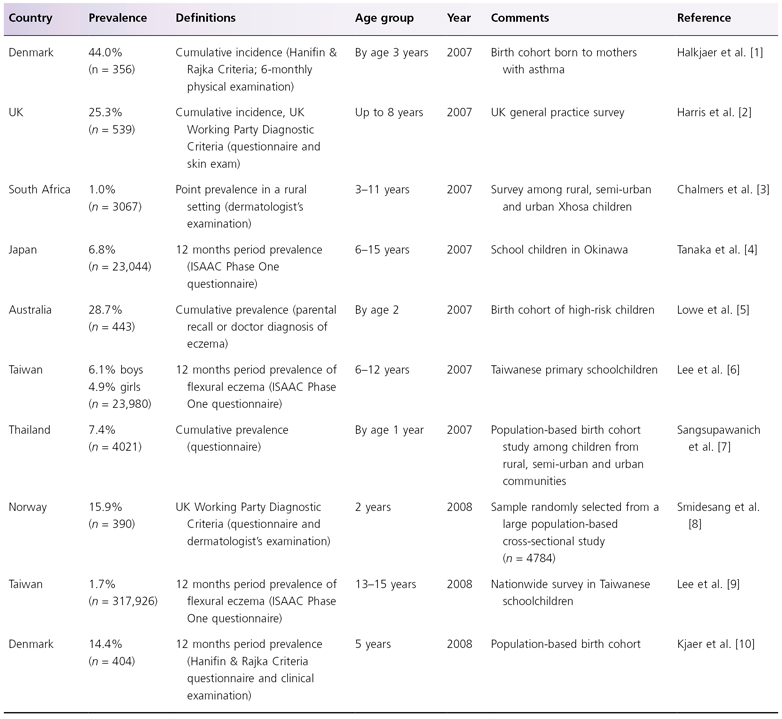

With so many different time periods and ways of recording AD, making comparisons of the prevalence of AD between countries is very difficult, and erroneous conclusions are likely to be drawn. For most epidemiological studies, the authors recommend that the 1-year period prevalence measure should be used, in order to reflect the intermittent nature of the disease and to overcome the effect of seasonality. A selection of recent prevalence surveys conducted throughout the world is presented in Table 22.1. Together, these surveys suggest that around 7–29% of children in developed countries suffer from AD [1–10]. The most comprehensive world map of symptoms of eczema, however, was published by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) [11].

Table 22.1 Recent worldwide prevalence surveys of atopic dermatitis

ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood.

Severity

In public health terms, the severity distribution of AD is more significant than the total prevalence of AD (which may include many mild asymptomatic cases), as severity is likely to determine those who use or need to use available health services. Few studies have rigorously examined the severity distribution of AD in the community, but indications are that severe cases are unusual [12,13]. One study found that the severity distribution of AD (defined by a dermatologist) in 1760 children living around Nottingham, England, was 84% mild, 14% moderate and 2% severe [14].

Morbidity

Few studies have quantified the morbidity of AD, but cases of AD often achieve the highest morbidity scores on generic disability measures when compared with other skin diseases in hospital studies [15]. Furthermore, impairment of quality of life appears to be directly related to the severity of atopic dermatitis [16]. The psychological morbidity associated with a lifetime of scratching, sleep loss and the stigma of a visible skin disease can also affect families to a considerable degree [17,18].

Cost

Atopic dermatitis can also be a costly disease. Costs-of-illness studies from the UK, the USA, Germany, Australia and The Netherlands suggest that overall expenditure associated with AD varies considerably between countries, ranging from US$71 in The Netherlands to US$2559 in Germany per patient per year. These variations are due to differences in the study populations (hospital versus community-based studies) and the cost components included [19,20].

Age, Sex and Natural History

In the majority of cases, AD starts in early life [21,22], although age of onset in milder community cases might be later [23]. Calculation of age of onset is dependent on the age of children surveyed, as younger children who do not have AD might still develop AD for the first time at a later age. Minor gender differences in AD, with a slightly higher prevalence among females, have been noted previously [24] but this is not a consistent finding [25].

Few longitudinal studies have examined the natural history of AD, and it should not be assumed that the prognosis of AD cases studied in a hospital setting (who are usually quite severe by definition) is the same as that for the majority of milder AD cases in the community [26]. Although one study suggested that around 90% of children are clear of their AD within 10 years [27], other studies of well-defined populations suggest that AD is a far more chronic condition with a clearance rate of around 60% by the age of 16 years [26,28]. True clearance rates are probably less than this, as many individuals relapse at some stage in adulthood (e.g. by developing irritant hand eczema). In the hospital setting, approximately 10% of patients still suffer from AD as adults [24]. Factors that may indicate a worse prognosis include severe childhood disease, early onset and a concomitant or family history of asthma or hay fever [25–28]. One birth cohort study of 1314 children followed to age 7 years in Germany (the Multicenter Allergy Study) deserves special mention because it included sequential physical examinations, parental interviews and specific IgE levels. Of the 21.5% of children with AD in the first 2 years of life, 43.2% were in complete remission by age 3 years, 38.3% had an intermittent pattern of disease, and 18.7% had symptoms of AD every year. A poorer prognosis was related to IgE sensitization (adjusted cumulative odds ratio 2.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.29–5.91) and early disease severity (adjusted cumulative odds ratio 5.86; 95% CI 3.04–11.29). Interestingly, early AD without early wheezing did not increase the risk of subsequent wheeze at school entry (adjusted odds ratio 1.11; 95% CI 0.56–2.20) [29].

Ethnic Group and Migrant Studies

Several studies have addressed ethnicity as an aetiological factor in AD, and particularly helpful are studies from communities of different ethnic origin in the same country. For instance, black Caribbean children born in the UK and children of Chinese origin born in the USA and Australia are at an increased risk of developing AD in comparison with their (mainly) white Caucasian peers [30–32]. As two of these studies recorded point prevalence of AD, it is difficult to say whether these differences were due to disease chronicity or disease incidence between ethnic groups. Another study of Asian children in Leicester (UK) found no difference in the prevalence of AD between different ethnic groups, although Asian children were three times as likely to be seen in the local dermatology department, perhaps reflecting lack of parental familiarity with the condition [33].

Migrant studies have been helpful in suggesting a strong role for the environment in the aetiology of AD [34]. Studies of Chinese immigrants in Hawaii and children from Tokelau who migrated to New Zealand found large increases in the prevalence of AD among migrant children compared with similar genetic groups in their country of origin [35]. Another study found that black Caribbean children living in London were around three times more likely to have AD than similar children living in Kingston, Jamaica, regardless of the method used to diagnose AD [30]. Together with similar observations for asthma, these migrant studies support the notion that environmental factors associated with urbanization and ‘western’ lifestyle are important in the aetiology of AD.

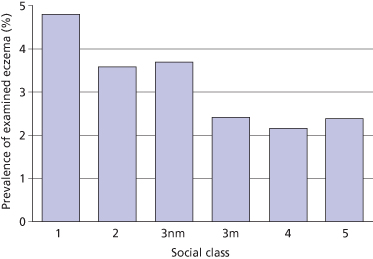

Social Class and Family Size

Reported eczema has exhibited a strong positive social class gradient (i.e. it is more common in higher socio-economic groups) [36]. Although such a trend could be due to enhanced reporting of eczema by mothers in advantaged socio-economic groups or increased labelling by doctors, an identical trend was found among children with examined eczema in a UK national birth cohort study in the 1970s (Fig. 22.2) [37]. Similar trends were shown for examined eczema and housing tenure. A reduced risk of AD has also been observed for children in larger families, especially if older siblings are present [38,39]. Similar findings have been reported for hay fever, asthma, skin test reactivity and allergen-specific IgE levels [40], and these observations led to the formulation of the so-called ‘hygiene hypothesis’ – the notion that reduced exposure to certain microbes might be responsible for the increase in allergy prevalence over past decades (see section on the hygiene hypothesis below).

Fig. 22.2 Social class and prevalence of examined eczema in a British cohort study of 8279 children aged 7 years.

Adapted from Golding & Peters 1987 [37].

Geographical Variation

While cross-sectional surveys suggest that up to about 30% of children in northern Europe and Australasia suffer from AD (see Table 22.1), some studies suggest that the disease is less common in many developing countries [41]. The notion that AD is rare in developing countries is now being challenged by recent data from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) that suggest that symptoms of AD are becoming increasingly common in cities in Latin America and Africa [42]. Furthermore, there tends to be a gradient between urban and rural areas within the same country. A clear urban–rural gradient has, for instance, been demonstrated in studies conducted in Sweden and Ethiopia [43,44], and an important factor involved may be traffic-related air pollution [9] (see also below). Another contributing factor may be water hardness. For instance, a recent ecological study conducted in the Nottingham area found that primary school children living in areas with harder tap water are more likely to develop AD than children living in soft-water areas [45], and a UK-based multicentre randomized controlled trial of water softeners for treating AD is currently under way [46].

Secular Trends

There is reasonable direct and indirect evidence to suggest that the prevalence of AD has increased two- to threefold over the last 30 years [47]. Some of these changes reflect secular trends in increased recognition of the disease by parents and doctors. However, similar trends over time have been observed for studies of skinprick tests, wheezing and hay fever, which are less prone to diagnostic labels. An increased prevalence of AD has been found in comparative cross-sectional surveys [25,47], and more convincingly in a recent population-based longitudinal study in Japan [48] and two large sequential worldwide eczema surveys conducted among almost 500,000 children aged 6–7 and 13–14 in 55 countries as part of the ISAAC [42]. The ISAAC surveys showed that eczema prevalence is still on the increase among younger children in both developed and developing nations, whereas eczema symptoms seem to be leveling off in some countries with previously high prevalence levels among 13 and 14 year olds. The reasons for this increase in AD are not clear, but environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals are the most likely explanation (see also section on AD risk factors below).

References

1 Halkjaer LB, Loland L, Buchvald FF et al. Development of atopic dermatitis during the first 3 years of life: the Copenhagen prospective study on asthma in childhood cohort study in high-risk children. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:561–6.

2 Harris JM, Williams HC, White C et al. Early allergen exposure and atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:698–704.

3 Chalmers DA, Todd G, Saxe N et al. Validation of the U.K. Working Party diagnostic criteria for atopic eczema in a Xhosa-speaking African population. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:111–16.

4 Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Arakawa M et al. Prevalence of asthma and wheeze in relation to passive smoking in Japanese children. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:1004–10.

5 Lowe AJ, Hosking CS, Bennett CM et al. Skin prick test can identify eczematous infants at risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37:1624–31.

6 Lee YL, Li CW, Sung FC et al. Environmental factors, parental atopy and atopic eczema in primary-school children: a cross-sectional study in Taiwan. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:1217–24.

7 Sangsupawanich P, Chongsuvivatwong V, Mo-Suwan L et al. Relationship between atopic dermatitis and wheeze in the first year of life: analysis of a prospective cohort of Thai children. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2007;17:292–6.

8 Smidesang I, Saunes M, Storrø O et al. Atopic dermatitis among 2-year olds: high prevalence, but predominantly mild disease – the PACT study, Norway. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:13–18.

9 Lee YL, Su HJ, Sheu HM et al. Traffic-related air pollution, climate, and prevalence of eczema in Taiwanese school children. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:2412–20.

10 Kjaer HF, Eller E, Høst A et al. The prevalence of allergic diseases in an unselected group of 6-year-old children. The DARC birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2008;19:737–45.

11 Asher MI, Bjorksten B, Lai CKW et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phase Three multicountry cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2006;368:733–43.

12 Williams HC, Pembroke AC, Forsdyke H et al. London-born black Caribbean children are at increased risk of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32:212–17.

13 Emerson RM, Charman CR, Williams HC. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score: preliminary refinement of the Rajka and Langeland grading. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:288–97.

14 Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. Severity distribution of atopic dermatitis in the community and its relationship to secondary referral. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:73–6.

15 Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:210–16.

16 Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Are quality of family life and disease severity related in childhood atopic dermatitis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:455–62.

17 Misery L, Finlay AY, Martin N et al. Atopic dermatitis: impact on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Dermatology 2007;215:123–9.

18 McKenna SP, Doward LC, Meads DM et al. Quality of life in infants and children with atopic dermatitis: addressing issues of differential item functioning across countries in multinational clinical. Trials Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;27:45.

19 Verboom P, Hakkart-van Roijen L, Sturkenboom M et al. The cost of atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands: an international comparison. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:716–24.

20 Mancini AJ, Kaulback K, Chamlin SL. The socioeconomic impact of atopic dermatitis in the United States: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:1–6.

21 Rajka G. Essential Aspects of Atopic Dermatitis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1989.

22 Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ et al. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:35–9.

23 Williams HC, Strachan DP. The natural history of childhood eczema: observations from the 1958 birth cohort study. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:834–9.

24 Schultz Larsen F. The epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. In: Burr ML (ed) Epidemiology of Clinical Allergy. Basle: Karger, 1993: 9–28.

25 Schäfer T, Heinrich J, Wjst M et al. Indoor risk factors for atopic eczema in school children from East Germany. Environ Res 1999;81:151–8.

26 Williams HC, Wüthrich B. The natural history of atopic dermatitis. In: Williams HC (ed) Atopic Dermatitis. The Epidemiology, Causes and Prevention of Atopic Eczema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 41–59.

27 Vickers CFH. The natural history of atopic eczema. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1980;92(suppl):113–15.

28 Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:925–31.

29 Rystedt I. Long-term follow-up in atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatol Venereol (Stockh) 1980;114(suppl):117–20.

30 Williams HC, Pembroke AC, Forsdyke H et al. London-born black Caribbean children are at increased of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32:212–17.

31 Worth RM. Atopic dermatitis among Chinese infants in Honolulu and San Francisco. Hawaii Med J 1962;22:31–4.

32 Mar A, Tam M, Jolley D et al. The cumulative incidence of atopic dermatitis in the first 12 months among Chinese, Vietnamese, and Caucasian infants born in Melbourne, Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:597–602.

33 Neame RL, Berth-Jones J, Kurinczuk JJ et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Leicester: a study of methodology and examination of possible ethnic variation. Br J Dermatol 1995;132:772–7.

34 Burrel-Morris C, Williams HC. Atopic dermatitis in migrant populations. In: Williams HC (ed) Atopic Dermatitis. The Epidemiology, Causes and Prevention of Atopic Eczema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 169–82.

35 Waite DA, Eyles EF, Tonkin SL et al. Asthma prevalence in Tokelauan children in two environments. Clin Allergy 1980;10:71–5.

36 Williams HC, Strachan DP, Hay RJ. Childhood eczema: disease of the advantaged? BMJ 1994;308:1132–5.

37 Golding J, Peters TJ. The epidemiology of childhood eczema. A population based study of associations. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 1987;1:67–79.

38 Williams HC, Strachan DP, Hay RJ. Eczema and family size. J Invest Dermatol 1992;98:601.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree