F, physiological; P, pathological; –, not occurring; +/– infrequent; +, common; ++, frequent.

Thumb- and Finger-Sucking

Thumb- and finger-sucking develops as a habit in 13–45% of children [1,2]. The habit is physiological in infants from the early months to 4 years (peak age about 20 months).

Aetiology.

The cause of thumb- or finger(s)-sucking is not fully understood [1]. It gives a feeling of warmth, pleasure and certainty. Trichotillomania in toddlers is often associated with thumb- or finger-sucking. In trichotillomania, thumb- and finger-sucking indicates the presence of inner conflicts. Sometimes the reason is simple, for example in order to avoid playing piano or playing an important tennis game.

Clinical Features.

Sucking of the thumb or the fingers may cause maceration of the finger tips. Among children, thumb-sucking is the most common cause of paronychia. Digit-sucking is also a cause of radial angular deformity, in which a finger or the thumb is abnormally separated from the other fingers [1] (Figs 180.1, 180.2).

Fig. 180.2 Deformity of the fingers of the same girl (as an adult) as in Fig. 180.1 after prolonged sucking.

If the habit persists, dental complications can develop [1]. Between the ages of 4 and 14 years, thumb- and finger-sucking may have a deleterious effect on dentofacial development [1,2]. A protective factor, especially against pacifier sucking, seems to be prolonged breast feeding [3].

Prognosis.

The prognosis is usually excellent. Only rarely will the habit continue into adulthood.

Differential Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is very easy and simple because the habit is observed. There are no differential diagnostic problems.

Other Physiological Habits

In neonates, reflex smile, ‘sobbing’ inspirations and myoclonic twitches are physiological habits. From birth to 1 year of age sucking of the thumb, finger(s), toe and lips is common. Other common habits are masturbation, rocking and rolling (head banging) and teeth grinding. Head banging is often dramatic and upsetting to other members of the family. Questions often asked by the parents are: (i) ‘will it cause brain damage?’ (the answer is always no); and (ii) ‘is it associated with an emotional disorder?’ (in most cases the answer is no) [1]. These habits are of pathological significance only when they persist beyond early childhood or occur in combination with other habits.

In children older than 1 year of age, nail biting, nose picking and habit tics may develop. Except for nail biting and nose picking, the symptoms warrant serious attention because they can be pathological. Males are more likely to have habit tics. Any stress factor needs to be identified and treated. Habit coughs are typical tics in adolescents. Chronic tic disorders can be the first signs of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome [4]. In this syndrome, motor and vocal tics of variable intensity develop between the ages of 2 and 15 years.

Prognosis.

Many repetitive habits disappear with age and have no pathological importance. However, persistence of these repetitive behaviour problems may be a manifestation of psychological distress, side-effects of drugs or a first sign of physical disease.

Differential Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is most often simple because the habit is observed. The clinician must distinguish between physiological and pathological behaviour. It may be difficult to diagnose early Gilles de la Tourette syndrome [4].

Onychotillomania and Onychophagia

Nail biting (onychophagia) and nail picking (onychotillomania) are very common, especially among children [5]. The incidence of nail biting has been reported to be 33% in children and 45% in teenagers [6–8]. Before the age of 10 years, the incidence of nail biting in the sexes is relatively equal. Thereafter it is more common in boys [9]. Its incidence in adults is much lower.

Aetiology.

Anxiety and stress play an important role in the aetiology of nail biting [6]. In most cases, nail biting cannot be categorized as a sign of psychological or psychiatric disease. Trichotillomania can be associated with nail biting, but rarely in children [10].

Clinical Features.

Damage to the cuticle, bleeding around the nails, distal onycholysis and short irregular nail plates are the clinical clues (Fig. 180.3). Nail dystrophy develops in more severe and persistent cases. Secondary periungual bacterial infection may occur as a complication.

Other sequelae of persistent nail biting are paronychia, periungual warts, melanonychia and osteomyelitis [5,11,12]. Nail biting may increase nail growth by 20% [6].

Rubbing the thumb nail and proximal nail fold with the index finger of the same hand results in characteristic median dystrophy. A longitudinal depression in the centre of the nail over its entire length is observed (Fig. 180.4).

Prognosis.

The incidence is highest in children and teenagers. This habit normally disappears in early adult life.

Differential Diagnosis.

Nail changes because of biting should be distinguished from other physical or chemical trauma, as well as from congenital abnormalities and acquired disorders. Median nail dystrophia should be distinguished from congenital dystrophia mediana canaliformis [11]. In most cases it is not difficult; the history is most helpful.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is seven times more common in children than in adults. It is 2.5 times more common in girls than in boys [13–15]. It is the most common form of artefactual disease after thumb- or finger-sucking [16]. The incidence is not really known, but at a child guidance clinic three cases of trichotillomania were diagnosed among 500 children [17].

Aetiology.

Trichotillomania in young children is a habit phenomenon that is not usually a sign of serious emotional disturbance. It is comparable with thumb- or finger(s)-sucking and nail biting. Trichotillomania occurring later in life, especially of long duration, tends to be more serious from a psychological perspective. Hair is an important symbol of biological maturity. Therefore, trichotillomania may indicate an unconscious, symbolic effort to deny maturity [14].

Pathology.

Microscopic examination of the hair roots (the trichogram), obtained by using a standardized method, shows few telogen or catagen hairs, but there is an increase in dysplastic and/or dystrophic hair shapes [18].

Trichotillomania is characterized by the presence of empty hair follicles among completely normal hairs. Residual fragments of partially extracted hair provides evidence of trauma. Clumped melanin and keratinized material is seen within the disrupted hair follicles (trichomalacia) and this picture is considered pathognomonic [14,19]. Follicular plugging with keratin debris may also be present. Hair shafts within the lower follicular duct appear small and sometimes have a corkscrew appearance. Extravasated erythrocytes are sometimes visible in the epidermis and around the follicles. Usually there is no infiltration of leucocytes, except when secondary infection develops. Completely normal anagen follicles are present in the affected areas.

Clinical Features.

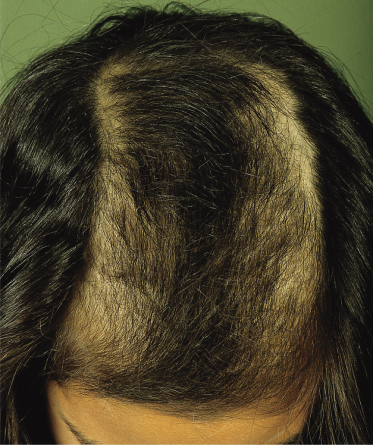

One or more areas of the scalp are affected. The areas may be quite small, or the process may involve almost the entire scalp [13]. In most cases, the areas of hair loss are not well demarcated. The eyebrows and eyelashes are sometimes affected. Most often, the areas of hair loss are contralateral to the handedness of the patient. Excoriation and crusts are sometimes visible on the scalp. The most typical pattern is an area of patchy alopecia surrounded by a rim of unaffected hair. This is called tonsure pattern alopecia or ‘Friar Tuck’ sign, for its resemblance to the hair style worn by monks [15,20] (Fig. 180.5).

Complications of trichotillomania are a permanent damage to hair, and hair ingestion (trichophagia) leading to a hairball (trichobezoar) in the stomach. Trichobezoar can lead to abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, foul breath, anorexia, obstipation, flatulence, anaemia, gastric ulcer, bowel obstruction or perforation, intestinal bleeding, obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis [20]. Trichobezoars weighing up to 412 g have been described [21].

Although trichotillomania in children usually presents as an isolated symptom, it may be associated with serious psychopathology such as mental retardation, depression, borderline disorder, schizophrenia, autism, obsessive–compulsive disorder and drug abuse [20]. However, it is commonly an anxiety condition in toddlers and is easily cured [14].

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes alopecia areata, psoriasis and tinea capitis. Clinical differential diagnosis between trichotillomania and alopecia areata may be difficult in some cases. History of hair pulling is often lacking, except in very young children, when the parents report the symptom [14]. The presence of an initial area of almost total hair loss favours alopecia areata. Exclamation hairs, a positive hair plucking test (loss of more than five hairs when pulled from the periphery of the bald area), pitting of the nails and depigmentation in regrowing hair in older children strongly support the diagnosis of alopecia areata. Laboratory examination will exclude tinea capitis.

Prognosis.

In many cases this symptom disappears with appropriate emotional support and when the child gains insight into the underlying psychological problems. However, one should not assume that trichotillomania will disappear spontaneously, therefore careful follow-up is required to establish resolution [14]. In a selected population, one-third of the patients required psychiatric treatment and guidance [14]. In serious and longstanding cases, psychological or psychiatric treatment is warranted.

Repeated manipulation of the hair in trichotillomania can lead to curly hair, trichorrhexis nodosa, other hair shaft fractures and, finally, to cicatricial alopecia.

Treatment.

In cases where the symptoms do not disappear spontaneously it is recommended that a psychiatrist and dermatologist join the treatment team. Behavioural therapy has a longstanding tradition in the treatment of trichotillomania with successful effect. More recently, a variety of drug treatments have also been investigated. Psychopharmacological medications include antidepressants; serotonergic agents and antipsychotics. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are known to be effective for depression, anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder, can also be effective in the treatment of trichotillomania. [22] In small children, oral medications will almost never be indicated or even necessary.

References

1 Peterson JE, Schneider PE. Oral habits. A behavioral approach. Pediatr Oral Health 1991;38:1289–307.

2 Lubitz L. Nail biting, thumb sucking, and other irritating behaviours in childhood. Austr Fam Physician 1992;21:1090–4.

3 de Holanda AL, dos Santos SA, Fernandes de Sena M, Ferreira MA. Relationship between breast- and bottle-feeding and non-nutritive sucking habits. Oral Health Prev Dent 2009;7(4):331–7.

4 Regeur L, Pakkenberg B, Fog R et al. Clinical features and long-term treatment with pimozide in 65 patients with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1986;49:791–5.

5 Oderick L, Brattstrom V. Nail biting: frequency and association with root resorption during orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthodont 1985;12:78–81.

6 Leung AKC, Robson WLM. Nail biting. Clin Pediatr 1990;29:690–2.

7 Massler M, Malone AJ. Nail biting – a review. J Pediatr 1950; 36: 523–31.

8 Wechsler D. The incidence and significance of finger-nail biting in children. Psychoanal Rev 1931;18:201–8.

9 Malone AJ, Massler M. Index of nail biting in children. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 1952;47:193–202.

10 Dimino-Emme L, Carmisa CH. Trichotillomania associated with the ‘Friar Tuck sign’ and nail biting. Cutis 1991;47:107–10.

11 Tosti A, Peluso AM, Bardazzi F. Phalangeal osteomyelitis due to nail biting. Acta Derm Venereol 1994;74:206–7.

12 Baran R. Nail biting and picking as a possible cause of longitudinal melanonychia. Dermatologica 1990;181:126–8.

13 Stroud JD. Hair loss in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 1983;30:641–57.

14 Oranje AP, Peereboom-Wynia JDR, De Raeymaecker DMJ. Trichotillomania in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15:614–19.

15 Muller SA. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Clin 1987;5:595–601.

16 Spraker MK. Cutaneous artifactual disease: an appeal for help. Pediatr Clin North Am 1983;30:659–68.

17 Anderson FW, Dean HC. Some aspects of child guidance clinic in policy and practice. Publ Health Rep 1956:71.

18 Peereboom-Wynia JDR. Hair root characteristics of the human scalp hair in health and disease. Thesis, Rotterdam, 1979.

19 Lachapelle JM, Pierard GE. Traumatic alopecia in trichotillomania. J Cutan Pathol 1977;4:51–67.

20 Hamdan-Allen G. Trichotillomania in childhood. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991;83:241–3.

21 Ewert P, Keim L, Schulte-Markwort M. Der Trichobezoar. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 1992;140:811–13.

22 Chamberlain SR, Menzies L, Sahakian BJ, Fineberg NA. Lifting the veil on trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatr 2007;164(4):568–74.

Self-Mutilation

Self-mutilation is defined as the deliberate alteration or destruction of one’s own body tissue without any conscious suicidal intent. The injury is done to oneself, without the aid of another person, and the injury is severe enough for tissue damage to result. Acts that are committed with conscious suicidal intent or are associated with sexual arousal are excluded [1,2].

Synonyms for self-mutilation are self-abusive behaviour, self-harm or self-injurious behaviour. A widely accepted term in dermatology is dermatitis artefacta as a synonym for self-mutilation. However, it also is used as a term for the skin lesions that are found in children and are inflicted by another person in factitious disorder by proxy.

Classification of Self-Mutilation

Several subgroups occur. Hollender and Abram described three groups. The first group consists of patients with an autoaggressive habitual behaviour and recognized, plausible motives, or those who are neurotic pickers and who readily admit to damaging their skin. The second group consists of patients with hysterical and obsessive impulses. The third group encompasses mentally retarded or psychotic individuals who self-mutilate frequently and in the presence of others [3]. Patients with delusions of parasitosis may also self-mutilate.

The most accepted classification of self-mutilation worldwide at the moment is the one developed by Favazza, namely superficial (compulsive and impulsive), stereotypic and major self-mutilation [4].

Comparing Hollender’s subgroups with Favazza’s classification shows that the first group consists of people/children with the impulsive type of superficial self-mutilation. Hollender’s second group is comparable with the compulsive type of the superficial self-mutilation group, and the third group can be compared with the stereotypic self-mutilation group. The group of patients with delusions of parasitosis can belong to either the superficial or the major self-mutilation group.

Self-injurious behaviour (SIB) as seen in children with autism or developmental disabilities is not the same as self-mutilation because usually there is no deliberate intent to harm one’s own body tissue.

Destruction of body tissue can be a result of repetitively stereotypic behaviour, stress due to over- or understimulation, impairment of communication skills, impairment of sensibility, somatic problems such as hearing problems or sight problems, and traumatization. The ontogenesis of SIB exhibited by young children with developmental disabilities is due to a complex interaction between neurobiological and environmental variables [5]. SIB in children with mental retardation starts at an early age: 68% starts before the age of 6 years. The prevalence of SIB in children with autism is 24–43%; the combination of both mental retardation and autism has a prevalence of more than 70% for SIB. Treatment involves behavioural therapy and/or psychomedication, depending on the liklihood of being able to change a patient’s behaviour [6,7].

Recently, a new classification was proposed based on adult patients:

1 Dermatitis artefacta syndrome in the narrower sense of unconscious/dissociated self-injury.

2 Dermatitis para-artefacta syndrome: admitted self-injury.

3 Malingering: consciously simulated injuries and diseases to obtain material gain.

4 Special forms, such as the Gardner–Diamond syndrome, factitious disorder (Munchausen syndrome) and the paediatric condition of falsification syndrome by proxy [8].

The authors of this chapter are not sure that this classification is useful and suitable for children.

Superficial Self-Mutilation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree