Fig. 160.2 Characteristic purpura on the buttocks of a child with Schönlein–Henoch purpura.

Courtesy of Dr Peter Hoeger, Hamburg.

In comparison to adults, paediatric patients more frequently show polymorphic SHP eruptions. Rarely, children may present with coalescent ecchymoses (Fig. 160.3) and haemorrhagic bullae that can result in ulceration and scarring. A minority of patients also display target-like lesions (Fig. 160.4) sometimes mimicking erythema multiforme. Veritable skin necrosis is observed in less than 5% of affected children [37,38].

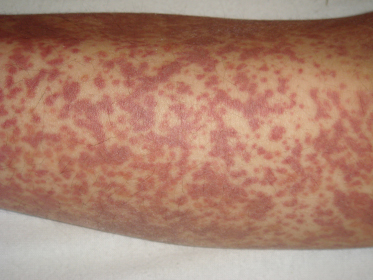

Fig. 160.3 Coalescent ecchymotic purpura on the legs of an adolescent with acute Schönlein–Henoch purpura.

Courtesy of Dr Peter Hoeger, Hamburg.

Fig. 160.4 Polymorphous Schönlein–Henoch purpura eruptions in a 7.5-year-old girl showing characteristic purpura and target-like lesions.

Courtesy of Dr Peter Hoeger, Hamburg.

Perhaps even more importantly, up to 5% of infants and young children (<2 years) who suffer from SHP will develop acral and facial swelling at disease onset. In a minority of patients, this may be the only presenting sign, and it has to be distinguished from other underlying conditions such as allergic angioedema or acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy [39].

Joint Manifestations

Nearly 80% of paediatric SHP patients suffer from additional arthralgia or non-destructive arthritis, which may be the only presenting sign in up to 25% of cases. Characteristically, SHP oligoarthritis is non-migratory mostly involving the knees and ankles, whereas joints of the upper extremities are less often affected.

Interestingly, patients with SHP arthritis during the initial episode develop joint symptoms significantly less often and less severely during disease relapses [40].

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement of variable severity is observed in 50–75% of patients. Typically about a week after the first occurrence of skin symptoms, affected individuals develop colicky abdominal pain with or without nausea caused by mesenteric vasculitis [41]. Furthermore, up to 22% of patients reveal positive faecal occult blood tests and 9% show elevated α1-antitrypsin serum levels as indicators of mucosal injury, which occurs even in patients without gastrointestinal complaints [36].

However, 14–36% of patients do not show any cutaneous abnormalities at the time of GI symptom onset. This may not only hamper adequate and swift diagnostic workup, but can also lead to unnecessary surgical procedures including laparotomy or appendectomy. Therefore, isolated gastrointestinal SHP represents a rare but relevant differential diagnosis of infantile and childhood acute abdomen [42].

Additionally, 75% of children reveal GI bleeding, which is usually occult, but melaena, haematochezia, haematemesis and, in rare cases, severe GI haemorrhages may occur. Further unusual but potentially serious GI complications include intussusception, acute pancreatitis, bowel perforation and protein-losing enteropathy. The latter is often characterized by abdominal pain, peripheral oedema and serum albumin levels of less than 30 g/L [43].

Renal Manifestations

More than 40% of children develop renal complications consisting of microscopic haematuria, proteinuria (25%), gross haematuria (5–10%), nephrotic syndrome or acute nephritis (5–20%) and, in the long term, end-stage renal disease (1–2%). Of note, these nephrological abnormalities almost never precede skin symptoms, but manifest within 4 weeks after the onset of cutaneous SHP in 85%, and within 6 months in nearly 100% of affected children. It is also noteworthy that infants and young children (<2 years) only rarely develop significant renal morbidity.

In general, SHP-associated renal manifestations have an excellent prognosis with complete resolution in the vast majority of patients. Apparently, the risk for later nephropathy is elevated in children older than 4 years of age with severe abdominal pain during the initial phase or purpuric lesions persisting more than 4 weeks [6]. As another important prognostic factor, crescents or tubulointerstitial pathologies upon kidney biopsy are associated with a poorer renal outcome [44]. Moreover, persistent proteinuria and severe renal symptoms (nephritic/nephrotic syndrome) at disease onset have been identified as independent predictors of a worse prognosis [45]. Terminally, only a very small proportion of all SHP patients (1–2%), but up to 21% of children with full-blown SHP glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome may suffer end-stage kidney disease [46]. Nevertheless, no single clinical feature reliably identifies the child at high risk for progressive renal impairment, which stresses the importance of a patient-tailored long-term follow-up, at least for patients with initial renal involvement.

Diagnostic Workup.

A careful history, including recent infections and medications, should be elicited for every patient along with a thorough physical examination. With that in mind, the diagnosis of SHP is mostly straightforward and can often be established on clinical grounds, especially if patients present with palpable purpura in dependent areas and further minor criteria such as arthritis or abdominal pain. The index of suspicion is also particularly high in children with concomitant upper respiratory tract infections or exposure to other plausible SHP trigger factors (see above). However, a wide range of differential diagnoses, especially for cutaneous SHP symptoms (Box 160.2), has to be considered if the clinical diagnosis is inconclusive.

Box 160.2 Selected Differential Diagnoses of Skin Symptoms in Schönlein–Henoch Purpura

Thrombocytopenia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenia

- Thrombotic thrombopenic purpura

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

- Drug-induced thrombocytopenia

- Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome

Coagulopathies

- von Willebrand syndrome

- Haemophilia

Autoimmune Disorders

- Wegener granulomatosis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Churg–Strauss syndrome

- Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

Infections

- Meningococcal septicaemia

- Bacterial endocarditis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Bone Marrow Failure

- Leukaemia

- Aplastic anaemia

Others

- Purpura pigmentosa progressiva

- Child abuse

Laboratory Investigations.

So far, no pathognomonic laboratory parameters for SHP have been identified, and reliable in vitro markers of disease severity or prognosis have not been established either. Hence, laboratory investigations are primarily performed to rule out possible differential diagnoses and to assess extracutaneous SHP complications.

As an initial screening, a complete blood count, a basic metabolic panel (blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes), coagulation studies (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time), urinalysis and a faecal occult blood test are recommendable, whereas anti-streptolysin O titres, blood cultures or antinuclear antibody tests represent second-line diagnostic steps. Other parameters such as serum levels of IgA, C3 or TGF-β are currently not recommended for routine use in daily clinical practice.

After discharge, only patients with renal abnormalities (proteinuria, macroscopic haematuria, hypertension) require laboratory monitoring at regular intervals, at least during the first 4 weeks, and referral to a paediatric nephrologist in case of symptom persistence.

Histology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree