Congenital cavernous haemangiomas may occur on the vulval skin, where they are more likely to become ulcerated due to the chafing effect of nappies. A further complication with a large haemangioma in this area is obstruction of the free flow of the urine, leading to pooling and bacterial contamination. The other causes of urinary pooling are labial adhesions and a microperforate hymen. In the latter, the normal escape of urine that enters the vagina on micturition is obstructed [18]. Threadworm infestation can be a cause of vulvovaginitis and this was reported in one series in nearly one-third of the cases and in one-half of these there was also a positive vaginal swab culture for bacteria [19]. An acute vulvitis has been described as an exanthema associated with parvovirus B19 infection [20].

Finally, the trauma of sexual abuse may result in inflammation with or without an associated sexually transmitted infection.

Clinical Features.

The skin signs seen in vulvovaginitis include erythema, oedema, erosions and fissuring of the vulva with an accompanying vaginal discharge. If the underlying condition is itchy, there will also be lichenification and excoriations. In severe inflammation, blisters and erosions develop. In the absence of a vaginal discharge, a vaginal infection is extremely unlikely.

The main symptoms that the child complains of include itch, vulval soreness, dysuria and discharge. The discharge is often yellow, green or brown and may be reported as having an unpleasant smell. A clear odourless discharge does not exclude an infection. The symptoms may be severe enough to interfere with sleep and the parents may notice blood or evidence of a discharge on the child’s underwear. Confirmation of the discharge is important as it is often reported but found infrequently on examination. In one study, only one-half of those reportedly having a discharge were found to have one when examined [21]. The discharge due to a foreign body often has an unpleasant odour.

Sometimes the vulval skin has very minimal changes of erythema but the vulval vestibule is very red and tender. This is usually the result of irritancy and the problem may be bubble baths or the harsh disinfectants used in swimming pools. The complaint is usually of a distressing stinging and/or burning sensation in the inner vulval area, often awaking the child suddenly in the night. There is usually an accompanying complaint of dysuria.

Diagnosis.

A careful history and thorough examination are essential to establish an accurate diagnosis. Any discharge must be fully investigated with samples for wet preparations to examine for Trichomonas and Candida, and further samples for Gram staining and bacterial culture. If herpes simplex is suspected, then viral culture and smear preparations for electron microscopy should be performed as well as serological testing. Any vaginal samples can be obtained without trauma and simple non-invasive techniques such as a swab of any discharge that has accumulated at the fourchette. If this is not possible, a vaginal specimen can be obtained using a neonatal suction catheter or a catheter within a catheter technique [22]. In this technique the hub of a butterfly infusion set with only the first 11.25 cm of the tubing still attached to it, the needle end having been cut off, is threaded into the distal end of an FG no. 12 bladder catheter that has been shortened to 10 cm. The butterfly hub is then attached to a 1 mL syringe filled with sterile saline. The uncut proximal end of the catheter is inserted into the vagina and the saline is then gently flushed through and aspirated. This aspirate is then examined and cultured. It is very important bearing in mind the confounding overlap between normal flora and potential pathogens that the finding of an organism does not necessarily mean that it is the cause of the discharge [2].

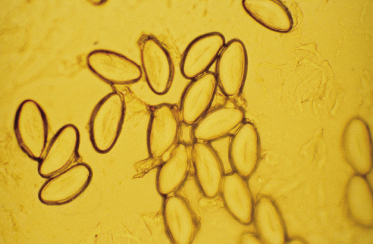

If intestinal worms are suspected, a sticky tape test should be performed in the morning to try and detect parasitic ova (Fig. 152.2). However, this is not always reliable and if the symptoms and signs are highly suggestive of infestation then this should be treated empirically.

An examination under anaesthetic may be required if there is a suspected foreign body, a persistent blood-stained or offensive smelling discharge and also in cases when a skin biopsy is indicated. A midstream specimen of urine should be taken for microscopy and culture and if gonorrhoea is suspected, nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAATs) can be used to detect Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the urine sample. In cases when candidiasis recurs without a background dermatosis then diabetes or immune deficiency must be excluded.

Treatment.

Treatment depends upon the diagnosis. If it is due to a dermatosis, the specific topical treatment for that condition will be necessary and general measures to prevent irritation will include washing with a soap substitute such as aqueous cream or emulsifying ointment, avoiding bubble baths or shampooing the hair in the bath. Topical barriers are useful and petroleum jelly can be used when swimming in heavily disinfected pools. If there is a proven infection or infestation, the appropriate antibiotic or anthelminthic agent should be prescribed. However, a change in perineal hygiene with emphasis on front-to-back wiping may be extremely effective in treating the immediate problem and preventing further episodes. Foreign bodies may be removed with gentle vaginal lavage after first anaesthetizing the vulva with topical lidocaine but if the object is firmly embedded in the vaginal wall or the child is very young or distressed, an examination under general anaesthesia will usually be required to remove it atraumatically.

References

1 Gerstner GJ, Grunberger W, Boschitsch E, Rotter M. Vaginal organisms in prepubertal children with and without vulvovaginitis. A vaginoscopic study. Arch Gynecol 1982;231:247–52.

2 Jaquiery A, Stylianopoulos A, Hogg G, Grover S. Vulvovaginitis: clinical features, aetiology, and microbiology of the genital tract. Arch Dis Child 1999;81:64–7.

3 Allen-Davis JT, Russ P, Karrer FM et al. Cavernous lymphangioma presenting as a vaginal discharge in a six-year-old female: a case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 1996;9:31–4.

4 Mulchahey K. Management Quandary. Persistent discharge in a premenarchal child. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2000;13:187–8.

5 Smith YR, Berman DR, Quint EH. Premenarchal vaginal discharge: findings of procedures to rule out foreign bodies. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2002;15:227–30.

6 Stricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Vaginal foreign bodies. J Paediatr Child Health 2004;40:205–7.

7 Stricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Vulvovaginitis in prepubertal girls. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:324–6.

8 Donald FE, Slack DB, Colman G. Streptococcus pyogenes vulvovaginitis in children in Nottingham. Epidemiol Infect 1991;106:459–65.

9 Cox RA, Slack MP. Clinical and microbiological features of Haemophilus influenzae vulvovaginitis in young girls. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:961–4.

10 Van Neer PA, Korver CR. Constipation presenting as recurrent vulvovaginitis in prepubertal children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:718–19.

11 Nair S, Schoeneman MJ. Acute glomerulonephritis with group A streptococcal vulvovaginitis. Clin Pediatr 2000;39:721–2.

12 Heller RH, Joseph JM, Davis HJ. Vulvovaginitis in the premenarcheal child. J Pediatr 1969;74:370–7.

13 Murphy TV, Nelson JD. Shigella vaginitis: report of 38 patients and a review of the literature. Pediatrics 1979;63:511–16.

14 Watkins S, Quan L. Vulvovaginitis caused by Yersinia enterocolitica. Pediatr Infect Dis 1984;3:444–5.

15 Fischer G. Vulval disease in pre-pubertal girls. Australas J Dermatol 2001;42:225–34.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree