Minor Aphthous Stomatitis

Syn.

Mikulicz ulcers

Minor aphthae are the most common, accounting for 80% of RAS. Ulceration usually begins in childhood or adolescence; there is a slight female sex predilection of 1 : 3. The lesions are usually of less than 10 mm, an average size being 3–4 mm in diameter, and they occur in crops of between one and five ulcers on non-keratinized mobile mucosa, i.e. floor of mouth, buccal or labial mucosa. The ulcers are round or ovoid, are shallow and have a white slough with an erythematous inflammatory halo. They heal within 7–10 days and rarely cause scarring (8%). They recur at intervals of between 1 and 4 months. However, crops of ulceration may be so frequent that the patient may never be ulcer free. As the child gets older, minor RAS tends to occur less frequently and may cease to be a problem.

Major Aphthous Stomatitis

Syn.

Sutton’s ulcers, periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens

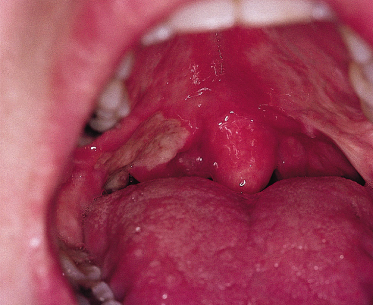

Major aphthae account for about 10% of all RAS. They are much larger than minor aphthae (being greater than 10 mm in diameter), typically 1.5–3.0 cm in diameter. They can occur anywhere in the mouth in crops of one to six ulcers and are much more painful than minor aphthae. They may have a firm raised margin but otherwise, apart from their size, have a similar clinical appearance to minor aphthae (Fig. 147.1). They take a month or more to heal. Healing often occurs with fibrosis, resulting in scarring (64%). Recurrence usually occurs after a shorter interval (within 4 weeks) than in the case of minor aphthae.

Herpetiform Ulceration

Herpetiform ulceration affects a slightly older age group (20–29 years). The clinical features are shown in Table 147.1.

Differential Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is made on the clinical appearance of the lesions and the clinical history. It is important to eliminate any underlying predisposing factors such as haematinic deficiencies, and to ask if genital ulceration is present in order to exclude Behçet syndrome. Biopsy is rarely indicated but may be carried out on major aphthae that have failed to heal, to eliminate neoplasia.

Treatment.

Treatment is symptomatic and often unsuccessful, unless an underlying predisposing factor is identified and corrected. In the majority of patients, RAS resolves spontaneously with age. If symptomatic treatment is required, it is best to approach therapy systematically, working through a variety of agents, beginning with those that have few or no side-effects until one is found that provides symptomatic relief.

Chlorhexidine gluconate (0.2%) or benzydamine hydrochloride mouthwashes or sprays are a good starting point and often give good symptomatic relief. The spray forms of these agents are particularly useful in children.

Topical tetracycline mouthwash, made up from a 250 mg capsule of tetracycline in 5 mL of water, may be useful, particularly in herpetiform ulceration. However, it is unsuitable for young children as they may ingest some of the mouthwash which can cause tooth discolouration.

Topical steroids such as hydrocortisone hemisuccinate pellets (Corlan® 2.5 mg four times daily) are often beneficial. Becotide 50 or 100 µg inhaler may be used as a topical mouth spray four to six times per day. A mouthwash made up of soluble betametasone tablets (0.5 mg) in 15–20 mL of water and held in the mouth for 3 min four times per day may be of benefit to adolescents but is not suitable for young children. Very occasionally, systemic steroids or other immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, colchicine and thalidomide have been necessary to control ulceration; their use in children must be carefully monitored and they should be used only as a last resort. There are multiple other therapies available for RAS, including carbenoxolone, benzydamine, dapsone, cromoglycate, levamisole and many others, but generally their efficacy has not been well proven or they have unacceptable adverse effects.

Behçet Syndrome

Definition.

Behçet syndrome is a multisystem disease in which the mouth is affected in nearly 100% of cases. Mouth lesions manifest as RAS. Other sites that may be affected include the genitals, eyes, skin and joints. There may be a number of other systemic or cutaneous manifestations. The clinical diagnosis of Behçet syndrome is dependent on the presence of at least three or more possible clinical manifestations, e.g. orogenital ulceration and uveitis (see Chapter 167).

Aetiology.

The aetiology of Behçet syndrome is unknown. There is increasing evidence to suggest an immunological aetiology; however, immunological findings appear to vary considerably and therefore cannot be used for the diagnosis or management of the disease. HLA-B5, HLA-BW51 and HLA-DR7 appear to be associated with Behçet syndrome.

Behçet syndrome can occur in any age group but most commonly affects adult males in their third decade, although it may occur in childhood.There is often a positive family history. There is also a higher prevalence of the disease in people from certain geographical areas, which include Japan, China, the Mediterranean and the Middle East [3].

Clinical Features.

The most common clinical feature is that of oral ulceration (90–100%), which may involve especially the posterior pharynx, and is indistinguishable clinically and histopathologically from RAS. Ulcers may occur at other sites, including the anus and genitals. Skin lesions such as erythema nodosum, pustules and pathergy are also common findings. The disease process is transient and subject to spontaneous remissions.

Differential Diagnosis.

Recurrent oral ulceration may be the first and only initial clinical feature of Behçet syndrome, but only a very few patients with RAS develop Behçet syndrome; however, Behçet syndrome must always be excluded when considering a diagnosis of RAS as, unlike RAS, it is a systemic disorder and is not self-limiting.

Oral and genital ulceration may also result from folate deficiency and, together with ocular lesions, may occur in erythema multiforme and ulcerative colitis.

Treatment.

Oral ulceration can be managed symptomatically as in RAS. Immunosuppressive treatment is required for those with other lesions. Results using ciclosporin and dapsone have been inconclusive, colchicine appears to be of value and thalidomide may be required in cases of recalcitrant orogenital ulceration but requires extreme caution as it is teratogenic.

MAGIC Syndrome

A condition that overlaps with Behçet syndrome and causes large joint arthropathies consists of mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage (MAGIC) [4].

Traumatic Ulceration

Trauma to the oral mucosa is common and may cause localized ulceration, which resolves as long as the causative agent is removed. It may be caused by sharp broken teeth or dental appliances or be self-inflicted, particularly with disorders such as congenital insensitivity to pain, Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, epilepsy, athetosis and learning impairment. Oral ulceration may also be caused by non-accidental injury. Radiation, thermal or chemical agents may also cause ulceration.

Clinical Features.

The clinical appearance of a traumatic ulcer is dependent upon the causative agent. Physical trauma gives rise to a localized ulcer that may resemble a minor or major aphthous ulcer. Tongue or cheek biting gives rise to a more irregularly shaped ulcer, often with a keratotic border. Thermal and chemical trauma caused by the ingestion of hot food or drinking caustic/acidic agents gives rise to more generalized ulceration, which tends to affect the tongue and palate. Ulcers may heal with scarring, especially if loss of connective tissue has occurred.

Oral ulceration due to non-accidental injury often occurs around the mouth and may involve the labial mucosa, particularly the labial fraenum, which may become torn and ulcerated by attempts to silence a child with a hand across the mouth.

Differential Diagnosis.

The possibility of other causes of oral ulceration should always be considered as described in this section.

Treatment.

Usually no treatment is required other than reassurance. If soreness is a problem, benzydamine hydrochloride may be useful as either a mouthwash or a spray. If the ulcer has been caused by a sharp tooth or orthodontic appliance, appropriate modification should be carried out. If self-mutilation is a problem, the provision of polyvinyl occlusal splints may be useful. If an ulcer fails to heal within 2–3 weeks after the causative agent has been removed, a biopsy should be considered to exclude neoplasia.

If child abuse is suspected, appropriate action should be taken, which is usually dependent upon local guidelines.

Infections

A variety of infections may give rise to oral ulceration/stomatitis. These will be considered under three main groups: viral, fungal and bacterial.

Viral Infections

The acute viral infections of childhood may give rise to oral ulceration and symptoms. The symptoms of acute viral infections affecting the mouth are all very similar, but the distribution of lesions may vary. Generally, if a viral infection is suspected, the diagnosis is made on clinical and epidemiological information. It is only where virus identification is of importance, such as in immunocompromised patients, that culture and nucleic acid/immunostaining studies to identify the virus are undertaken.

Herpetic Gingivostomatitis (See Chapter 48)

Aetiology.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 and increasingly type 2 cause primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Primary herpes most commonly occurs in young children (2–4 years) and is often subclinical; however, many children now reach maturity without acquiring immunity to the virus, giving rise to an increased incidence of primary herpes infections in young adults. Primary herpes infection is twice as common in lower socio-economic groups. Herpes simplex virus is found in the saliva in both primary and secondary infections, and may be spread in this way. The incubation period is 3–7 days.

Pathology.

Well-defined fluid-filled vesicles form in the upper epithelium. The vesicles rupture, infecting the epithelium throughout its entire thickness. Ulceration is caused by shedding of the virus-damaged epithelial cells.

Clinical Features.

The lesions consist of well-defined vesicles of about 2 mm in diameter, which may coalesce to form larger irregular lesions that may be distributed over the entire oral mucosa and gingivae but are commonly seen on the dorsum of the tongue and the hard palate. The vesicles rapidly rupture to form circular, sharply defined shallow ulcers with a yellowish-grey floor and erythematous margin (Fig. 147.2). The ulcers are very painful. The gingival margins are usually enlarged and inflamed. There is often associated cervical lymphadenopathy, pyrexia and general malaise. Diagnosis is usually made on the clinical features.

Differential Diagnosis.

Acute ulcerative gingivitis, erythema multiforme and leukaemia may occasionally give a similar clinical appearance, as may hand, foot and mouth disease and herpangina (see below). Gingival enlargement may be seen in acute childhood leukaemia, particularly the myeloid type.

Treatment.

In most cases, the infection resolves spontaneously with 7–10 days. For the majority of patients the management is supportive, with antipyretic analgesics (e.g. paracetamol/acetaminophen), bed rest and adequate fluid intake. Chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2% mouthwash or spray may help to prevent secondary infection of the ulcers.

Systemic aciclovir or similar antiviral agents hasten recovery but are only really useful if used in the first 3 days of onset, during the vesicular stage of infection [5]. As most cases present in the ulcerative phase, this is of little benefit. Aciclovir does have a role to play if patients are immunocompromised, and in rare complications such as encephalitis and neuropathy.

Recurrent Herpes Simplex

Following primary infection, the herpes virus remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion. About one-third of patients experience recurrent herpes infections, the most common form of which is herpes labialis (cold sore) (Fig. 147.3). Typical triggering events include exposure to sunlight, infections such as the common cold, stress and trauma.

Intraoral recurrence often manifests as a dendritic ulcer on the tongue or palate. Chronic ulceration of this type or nodular lesions can occur in immunosuppressed individuals and may require treatment with systemic aciclovir.

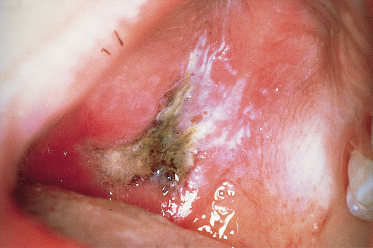

Aciclovir-Resistant Herpes Simplex Infection

Severely immunocompromised children, such as those undergoing bone marrow transplantation, may develop aciclovir-resistant herpes simplex infections. The clinical appearance of this condition is almost pathognomonic of the infection (Figs 147.4, 147.5). The lesions present as well-defined oral ulcers with a characteristic adherent greyish-white slough, which has a leathery texture [6]. The usual oral features of either primary or recurrent herpes are not usually present. The patients are nearly always on a prophylactic regimen of aciclovir, and many have a history of previous herpes labialis [7]. The herpes virus may also be resistant to ganciclovir and foscarnet, which is nephrotoxic and has been used to treat the virus. Valaciclovir and cidofovir are alternative treatments. Aciclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus has also been reported in immune incompetence as a result of HIV infection and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome [8].

Fig 147.4 Aciclovir-resistant herpes on the ventral surface of the tongue of a child following bone marrow transplantation. Note the well-defined lesion and the absence of an inflammatory reaction surrounding the lesion.

Fig. 147.5 Aciclovir-resistant herpes on the hard palate of a child following bone marrow transplantation.

Chickenpox

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella zoster virus. Lesions occur mainly over the trunk but may also occur intraorally. The oral lesions appear as vesicles, which break down to form discrete, well-defined ulcers. They are usually fewer in number than in primary herpes and there is no associated gingival enlargement.

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

Herpes zoster may give rise to oral lesions if the maxillary or mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve is involved. Ulcers appear in the distribution of the affected nerve; the lesions do not cross the midline and are preceded by a toothache-like pain. It is rare to see herpes zoster in childhood unless the child is immunocompromised or the mother was infected during pregnancy.

Herpangina

Herpangina is caused by a Coxsackie A virus. The infection is usually confined to children and presents as an acute pharyngitis with lymphadenopathy and pyrexia. Oral lesions are localized to the soft palate; they resemble those of primary herpes. There is no gingival involvement. The infection resolves spontaneously in 10–14 days. Treatment is supportive, as described for primary herpes.

Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease

Hand, foot and mouth disease often causes minor epidemics among school children. It is caused by a Coxsackie A virus, usually A10 or A16, or occasionally a Coxsackie B or other enterovirus.

Clinically, the oral lesions resemble those of primary herpes, although they occur in much smaller numbers and cause few symptoms. As in herpangina, the gingivae are not involved. Cutaneous lesions affect the hands and feet and consist of small deep-seated vesicles, with surrounding erythema situated on the digits or base of the phalanges. Management is as for herpangina.

Infectious Mononucleosis (Epstein–Barr Viral Infection)

Infectious mononucleosis is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). In the Western world, it is more common in teenagers and young adults, but it may occur in children. Oral symptoms include sore throat, and palatal petechiae are often evident. Occasionally, there may be severe ulceration of the fauces; less severe non-specific oral ulceration and pericoronitis may also occur.

Cytomegalovirus Infection

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) may cause a glandular fever-type illness but rarely causes oral ulceration. Persistent CMV-induced ulcers have been described in immunosuppressed patients [9]. Persistent oral ulcers in immunosuppressed patients should be biopsied and sent for histopathology, microbiological culture and PCR DNA studies.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Oral ulceration may occur in children who are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive. Clinically, they are often aphthous-like [10] and may be treated as such. However, the possibility of another infective cause should always be considered, e.g. CMV [11].

Fungal Infections

Oral fungal infections rarely cause ulceration of the oral mucosa in the Western world except in immunocompromised or debilitated patients. In the tropics, otherwise healthy individuals may occasionally present with oral fungal lesions caused by endemic deep mycoses.

Deep Mycoses

Deep mycotic infections are uncommon in the UK but are seen in Latin America and some parts of the southern USA. Oral lesions are most common in histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis but have been described in all mycoses. The oral lesions are not distinctive and diagnosis is usually made on biopsy.

The following deep mycoses may give rise to oral ulceration in the immunocompromised child, particularly those undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation, or in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). They should always be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in the immunocompromised and, if necessary, biopsied to exclude them as causative agents.

Aspergillosis may cause black necrotic ulceration of the palate (Fig. 147.6). The infection usually originates from infection in the maxillary sinuses and is caused by direct invasion of the palate. Diagnosis is made from biopsy and radiographic examination of the paranasal air sinuses. Treatment is usually with intravenous itraconazole or amphotericin.

Fig. 147.6 Necrotic ulceration of the hard palate due to antral aspergillosis in a child following bone marrow transplantation.

Mucormycosis (zygomycosis, phycomycosis), infection with a fungus associated with mouldy bread, may give rise to a similar clinical picture to aspergillosis. It is a condition that has been associated with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

Histoplasmosis oral lesions are uncommon and present as a non-specific ulcer or lump. They are usually seen in chronic disseminated histoplasmosis.

Bacterial Infections

Acute Ulcerative Gingivitis

Acute ulcerative gingivitis (AUG) is an uncommon disease in childhood and may be associated with immune deficiency such as AIDS and cytotoxic chemotherapy. In countries where nutrition is poor, it can manifest as cancrum oris (noma), causing massive soft tissue destruction. It is thought to be caused by a proliferation of two normal oral commensals, the Gram-negative anaerobes Borrelia vincentii and Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Classically, AUG begins on the tips of the interdental papillae, causing intense pain and halitosis. Spontaneous bleeding of the gingivae may occur. The ulceration spreads along the gingival margin but is well localized. In the immunocompromised child, the ulceration may be far more destructive and spread onto the palate, and buccal sulci may occur. Histologically, there is intense inflammation and destruction of the epithelium and connective tissue.

When occurring in a young child, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis may give a similar gingival appearance, but it is unusual for ulceration to be localized to the gingivae. Systemic upset is usually more severe in primary herpes.

Acute ulcerative gingivitis responds rapidly to metronidazole therapy three times daily for 3 days, the dose depending upon age. If the child is immunocompromised, a longer course and higher dose may be indicated. Local measures such as improving oral hygiene and the use of an antibacterial mouthwash (e.g. chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2%) should also be considered.

Other Bacterial Infections

Tuberculosis and syphilis are rare causes of chronic mouth ulcers.

Oral Ulceration in Association with Neoplasia

Oral carcinoma is extremely rare in children. Very occasionally, oral ulceration may be the presenting feature of a malignant lesion, particularly lymphoma or histiocytosis. Any chronic oral ulcer in a child with no obvious causative factors should therefore be biopsied.

Oral Ulceration Associated with Systemic Disease

Oral ulceration may occasionally be the presenting feature of other systemic disease. The relationship of oral ulceration to systemic diseases will be discussed in this section with reference only to the systemic disease and oral features.

Haematological Disorders

Haematinic deficiencies are discussed above. Immunodeficiencies, whether congenital or acquired, may also give rise to oral ulceration. These ulcers usually resemble recurrent aphthae but if a neutropenia is present, they lack the erythematous inflammatory halo, as in cyclic or hereditary benign neutropenias (Fig. 147.7).

Fig. 147.7 Neutropenic ulcers in a child with familial chronic neutropenia. Note the lack of inflammation surrounding the ulcers.

Gastrointestinal Disease

As discussed with RAS, haematinic deficiencies may give rise to oral ulceration, therefore any gastrointestinal disease causing malabsorption predisposes the child to oral ulceration.

Coeliac Disease (Gluten-Sensitive Enteropathy)

Older children and adolescents with undiagnosed coeliac disease may occasionally present with sore mouths. Oral manifestations include recurrent ulcers, glossitis, angular stomatitis and dental hypoplasia, related to underlying haematinic and vitamin deficiencies.

Crohn Disease

Oral lesions related to Crohn disease include facial or labial swelling (orofacial granulomatosis), oral ulcers, which may be large and ragged or linear in appearance, mucosal tagging or proliferation of the oral mucosa to give a ‘cobblestone’ appearance. Other lesions, such as ulcers and glossitis, may be due to an associated nutritional deficiency caused by malabsorption or may be coincidental.

Oral lesions may occur prior to any gastrointestinal symptoms. Biopsy of the oral lesions will confirm the diagnosis, histology showing non-caseating granulomas in the corium with an overlying normal or ulcerated epithelium. Differential diagnosis includes orofacial granulomatosis, sarcoidosis and tuberculosis (see below and Chapters 57, 157, 158).

Treatment of the oral lesions is dependent upon whether there is active gastrointestinal disease. If systemic corticosteroid or aminosalicylate therapy for active gastrointestinal disease is used, the oral lesions may also improve; if oral lesions remain symptomatic or occur in isolation, local measures to control the symptoms, such as those used in RAS, may be adequate.

Orofacial granulomatosis is a term given to labial or gingival swelling due to a granulomatous reaction but without any detectable systemic cause, e.g. Crohn disease, sarcoidosis. Some patients with this diagnosis will go on to develop a systemic disease some time later. In other cases, the granulomatous reaction is thought to be due to a food allergy, particularly to cinnamon-containing foodstuffs. Exclusion of cinnamon from the diet of these individuals may allow resolution of the lesions. A short course of high-dose or intralesional steroids may reduce swelling [12].

Ulcerative Colitis

Oral lesions associated with ulcerative colitis include aphthous-type ulceration and glossitis, which may be associated with anaemia. Other oral lesions are rare and include haemorrhagic ulceration of the mucosa, chronic oral ulceration resembling pyostomatitis gangrenosum of the skin and pyostomatitis vegetans, which clinically gives rise to hyperplastic folds of the oral mucosa between which microabscesses or fissures form; multiple yellowish pustules may also form on the mucosa.

Behçet syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis of oral lesions. Treatment is the same as in Crohn disease, oral lesions being more apparent with exacerbations of bowel inflammation.

Dermatological Disorders

Dermatological disorders rarely cause mouth ulcers in children; if they do occur, skin lesions can often aid diagnosis.

Lichen Planus, Lichenoid Reactions and Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease

Lichen planus is rare in childhood. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of oral white lesions in children, particularly in children of Asian origin [13]. Drug-induced lichenoid lesions may occur; they are particularly associated with the use of anti-inflammatory agents, antihypertensives and antimalarial drugs. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following organ or bone marrow transplantation may also give rise to lichenoid lesions.

Clinically, several forms of lichen planus may be observed. Reticular and papular lichen planus is usually asymptomatic and is usually symmetrically distributed on the buccal mucosa and lateral borders of the tongue. It may resemble oral thrush, particularly if it is plaque-like in appearance. These white forms of lichen planus often require no treatment if they are symptomless.

Atrophic or erosive lichen planus is symptomatic and may be seen in GVHD. It presents as erosive, often linear ulcers, which affect any site but commonly the tongue and buccal mucosa (Fig. 147.8). It is unlikely to be the only clinical manifestation of GVHD. Skin and liver GVHD are often concurrent, requiring the use of immunosuppressive therapy. The immunosuppressive therapy does not always resolve the oral GVHD, and topical steroid therapy using Becotide 50 or 100 inhaler as a topical mouth spray four to six times per day, together with soluble betametasone 0.5 mg (Betnesol) used as a mouthwash (dissolved in 25 mL of water) and held in the mouth for 2–3 min four times per day, may aid healing and improve symptoms. Benzydamine hydrochloride mouthwash or spray may also be of symptomatic use. It is also important to keep the mouth as clean as possible, to prevent secondary infection. As tooth brushing may be painful, the use of chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash 0.2% or spray twice daily may be helpful. As the GVHD responds to the immunosuppressive therapy, oral lesions usually resolve.

Fig. 147.8 Erosive lichen planus-like lesions of the tongue due to GVHD. Note also the depapillation of the tongue.

Vesiculobullous Disorders

The more common dermatological conditions that cause vesiculobullous lesions in the mouth, such as pemphigus vulgaris and mucous membrane pemphigoid, are very rare in childhood and will not be discussed. Oral vesicles or bullae may occur in childhood in benign familial chronic pemphigoid, which break down to form well-demarcated ulcers.

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is discussed in Chapter 118. In most forms of the disease, bullae will form on the oral mucosa. They usually appear in infancy and may be precipitated by suckling. The bullae break down to form ulcers, which heal slowly, usually with scarring. The tongue becomes depapillated. Because of the sensitivity of the mucosa to trauma, oral hygiene is usually poor and the incidence of caries and periodontal disease is therefore high.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis and Linear Immunoglobulin A Disease

Dermatitis herpetiformis may occur in childhood and is often associated with gluten enteropathy (see Chapter 89). Oral lesions may occur and include erythematous papules and macules, petechiae, vesicles, bullae and erosions. Similar oral lesions may occur in linear immunoglobulin A (IgA) disease. Oral lesions rarely occur in isolation and will respond to therapy for cutaneous lesions, dapsone or sulfapyridine. Diagnosis is made on biopsy.

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme is discussed in Chapter 78. Oral features characteristically include swollen, bleeding, crusted lips and widespread oral ulceration. Oral ulcers are preceded by erythematous macules, which become vesicles. Intact vesicles are rarely seen as they rapidly break down to form ill-defined ulcers. The tongue is often furred and there may be regional lymphadenitis. Oral lesions may occur in isolation or with a skin rash, which characteristically consists of ‘target’ lesions and ocular involvement.

The combination of oral lesions, skin lesions and conjunctivitis is referred to as Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

Biopsy may be necessary in less characteristic cases and will exclude other vesiculobullous disorders and Behçet syndrome.

Aciclovir may be beneficial prophylactically in herpes-precipitated erythema multiforme.

Connective Tissue Disorders

Connective tissue disorders that give rise to oral ulceration, e.g. systemic and discoid lupus erythematosus, rarely occur in children. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis may be associated with anaemia, which may predispose to RAS. Felty syndrome is most likely to cause ulceration, presumably because of the associated neutropenia. Behçet syndrome may occur in childhood and is discussed above.

Iatrogenic Oral Ulceration

Oral ulceration may regularly be caused by certain drugs, e.g. cytotoxic agents. The ulceration is usually aphthous-like in appearance but may lack an inflammatory halo if associated with neutropenia. It is self-limiting and heals within 7–10 days. It is now less commonly seen in association with methotrexate as folinic acid rescue (calcium leucovorin) is usually always given with high-dose methotrexate therapy. Aphthous-type ulceration can also occur in long-term use of some drugs, such as phenytoin or co-trimoxazole, which interfere with folate metabolism. Aplastic anaemia may also be drug induced and give rise to oral ulceration and purpura.

Radiation to the head and neck, and total body irradiation for bone marrow transplantation, gives rise to mucositis, which occurs 7–10 days after beginning radiotherapy to the head and neck, and lasts for up to 4 weeks after completion of treatment. Those patients undergoing total body irradiation experience mucositis within 5–10 days and the mucositis heals within 2–3 weeks of treatment.

Various agents have been used to decrease the amount of mucositis and improve healing; however, none has been particularly successful apart from oral cooling with ice. Treatment therefore remains symptomatic; benzydamine hydrochloride and chlorhexidine mouthwash may help alleviate symptoms.

References

1 Scully C, Gorsky M, Lozada-Nur F. The diagnosis and management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a consensus approach. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:200–7.

2 Field AE, Brookes V, Tyldesley W. Recurrent aphthous ulceration in children: a review. Int J Paediatr Dent 1992;2:1–10.

3 Escudier M , Bagan J, Scully C. Behcets syndrome (Adamantiades syndrome). Oral Dis 2006;12:78–84.

4 Firestein GS, Gruber HE, Weisman MH et al. Mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage: MAGIC syndrome. Am J Med 1985;79:65–71.

5 Amir J, Harel L, Smetana Z et al. Treatment of herpes simplex gingivostomatitis with aciclovir in children: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. BMJ 1997;314:1800–3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree