12 Eyelid and Periocular Reconstruction

Abstract

“Eyelid and Periocular Reconstruction” sets out principles for reconstruction after eyelid tumor excision in order to preserve normal eyelid function for the protection of the eye and, if possible, restore good cosmesis. Preservation of normal function is of the utmost importance and takes priority over the cosmetic result. Failure to maintain normal eyelid function, particularly after upper eyelid reconstruction, will have dire consequences for the patient’s comfort and visual performance. In general, it is technically easier to reconstruct eyelid defects after tumor excision surgery than after trauma. If less than 25% of the eyelid has been sacrificed, direct closure of the eyelid is usually possible. If the eyelid tissues are very lax, direct closure may be possible for much larger defects occupying 50% or more of the eyelid. If direct closure is difficult without undue tension on the wound, a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis of the appropriate limb of the lateral canthal tendon can facilitate a simple closure. A variety of surgical procedures have been devised to reconstruct more extensive defects. The choice depends on the extent of the defect, the condition of the remaining periocular tissues, the visual status of the opposite eye, the age and general health of the patient, and the surgeon’s own expertise.

12.1 Introduction

The goals in eyelid and periocular reconstruction after eyelid tumor excision are preservation of normal eyelid function for the protection of the eye and restoration of good cosmesis. Of these goals, preservation of normal function is of the utmost importance and takes priority over the cosmetic result. Failure to maintain normal eyelid function, particularly after upper eyelid reconstruction, will have dire consequences for the patient’s comfort and visual performance. In general, it is technically easier to reconstruct eyelid defects after tumor excision surgery than after trauma.

12.2 General Principles

A number of surgical procedures can be used to reconstruct eyelid defects. In general, if less than 25% of the eyelid has been sacrificed, direct closure of the eyelid is possible. If the eyelid tissues are very lax, direct closure may be possible for much larger defects occupying 50% or more of the eyelid. If direct closure without undue tension on the wound is difficult, a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis of the appropriate limb of the lateral canthal tendon can facilitate a simple closure.

To reconstruct eyelid defects involving greater degrees of tissue loss, a number of different surgical procedures have been devised. The choice depends on several factors:

The extent of the eyelid defect.

The state of the remaining periocular tissues.

The visual status of the fellow eye.

The age and general health of the patient.

The surgeon’s own expertise.

When deciding which procedure is most suited to the individual patient’s needs, the surgeon should aim to reestablish the following:

A smooth mucosal surface to line the eyelid and protect the cornea.

An outer layer of skin and muscle.

Structural support between the two lamellae of skin and mucosa originally provided by the tarsal plate.

A smooth, nonabrasive eyelid margin free from keratin and trichiasis.

In the upper eyelid, normal vertical eyelid movement without significant ptosis or lagophthalmos.

Normal horizontal tension with normal medial and lateral canthal tendon positions.

Normal apposition of the eyelid and lacrimal punctum to the globe.

A normal contour to the eyelid.

Large eyelid defects generally require composite reconstruction in layers with a variety of tissues from either adjacent sources or from distant sites being used to replace both the anterior and posterior lamellae. It is essential that only one lamella be reconstructed as a free graft. The other lamella should be reconstructed as a vascularized flap to provide an adequate blood supply to prevent necrosis of the graft.

Many different techniques have been described for use in periocular reconstruction. The techniques described in this chapter are those I use most. It is wise to master the simpler techniques before attempting more complex reconstructions. A combination of techniques may have to be used for more extensive defects.

12.3 Lower Eyelid Reconstruction

Defects of the lower eyelid can be divided into those that involve the eyelid margin and those that do not.

12.4 Eyelid Defects Involving the Eyelid Margin

12.4.1 Small Defects

An eyelid defect of 25% or less may be closed directly in most patients. In patients with marked eyelid laxity, even a defect occupying up to 50% or more of the eyelid may be closed directly. The two edges of the defect should be grasped with toothed forceps and pulled together to judge the facility of closure. If there is no excess tension on the lid, the edges may be approximated directly.

12.4.2 Direct Closure

Surgical Procedure

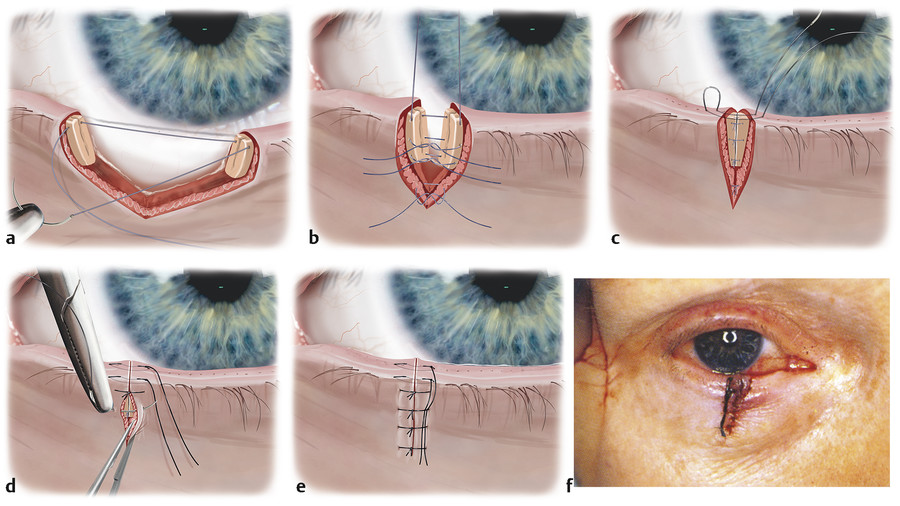

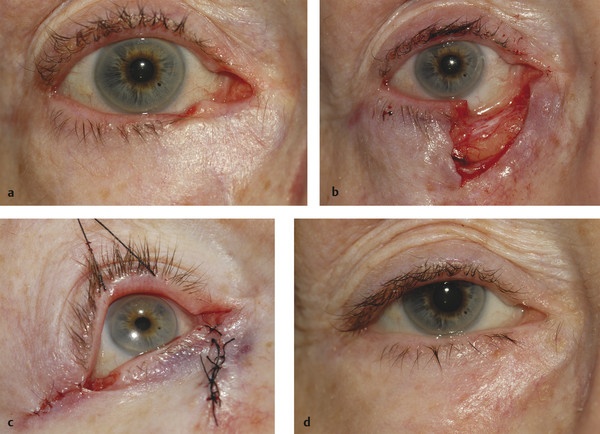

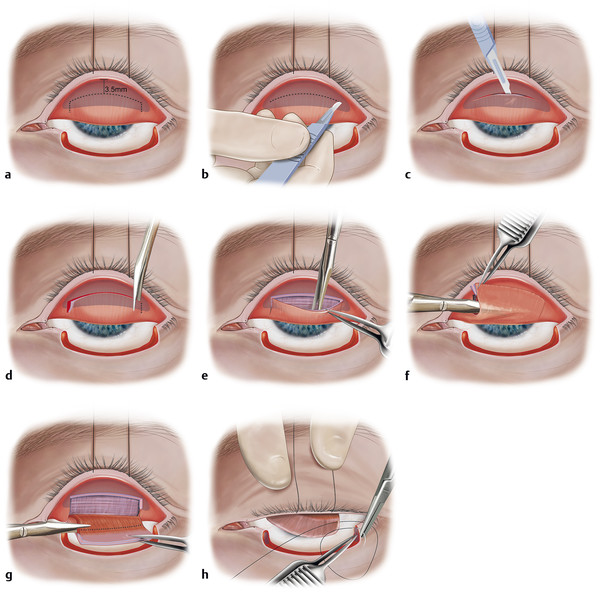

A single-armed 5–0 Vicryl suture on a half-circle needle loaded on a Castroviejo needle holder is passed through the most superior aspect of the tarsus just below the eyelid margin, ensuring that the needle and suture are anterior to the conjunctiva to avoid contact with the cornea (Fig. 12‑1a).

This suture is tied with a single throw and the eyelid margin approximation checked. If this is unsatisfactory, the suture is replaced and the process repeated. Proper placement of this suture will prevent the complications of eyelid notching and trichiasis and wound dehiscence. Once the margin approximation is good, the suture is untied and the ends fixated to the head drape with a curved artery clip. This elongates the wound, enabling further single-armed 5–0 Vicryl sutures to be placed in the tarsus inferiorly (Fig. 12‑1b).

Additional 5–0 sutures are then passed through the orbicularis muscle and tied (Fig. 12‑1c).

A single-armed 6–0 black silk suture on a reverse cutting needle loaded on a Castroviejo needle holder is passed through the eyelid margin along the line of the meibomian glands 2 mm from the wound edge, emerging 1 mm from the surface. The needle is remounted and passed similarly through the opposing wound, emerging 2 mm from the wound edge. The suture is cut, leaving the ends long. The same suture is passed in a similar fashion along the lash line and cut, leaving the ends long (Fig. 12‑1d).

Next, the 6–0 silk sutures are tied with sufficient tension to cause eversion of the edges of the eyelid margin wound. A small amount of pucker is desirable initially to avoid late lid notching as the lid heals and the wound contracts. The sutures are left long and incorporated into the skin closure sutures to prevent contact with the cornea (Fig. 12‑1e,f).

The skin is closed with simple interrupted 6–0 black silk sutures.

Topical antibiotic ointment is instilled into the eye and the eye closed.

A Jelonet dressing is placed over the eye, followed by two eye pads, and a firm compressive bandage is applied to prevent excessive swelling.

Postoperative Care

The dressing is removed after 48 hours and topical antibiotic ointment applied three times per day to the eyelid wound for 2 weeks. The 6–0 sutures are removed in clinic after 2 weeks.

12.4.3 Moderate Defects

Canthotomy and Cantholysis

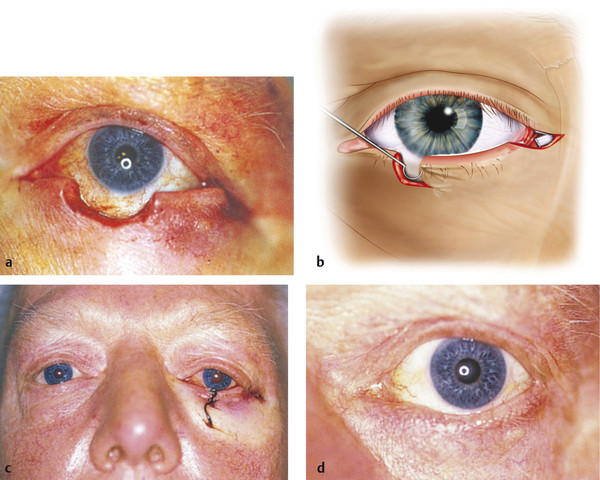

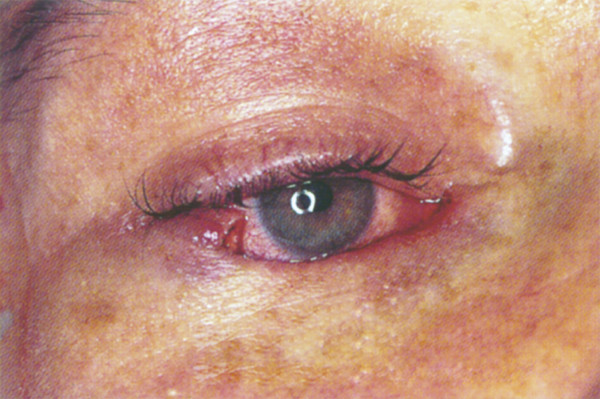

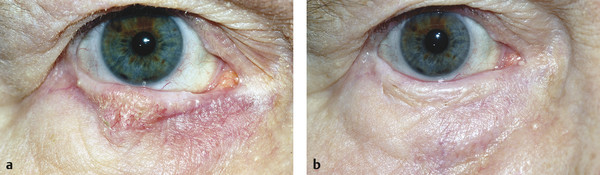

If the eyelid defect cannot be closed directly without undue tension on the wound, a lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis can be performed. A combination of direct closure and laissez-faire healing can also be very effective (Fig. 12‑2).

Surgical Procedure

Using a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade, a 4- to 5-mm horizontal skin incision is made at the lateral canthus. This is deepened to the periosteum of the lateral orbital margin using curved Westcott scissors.

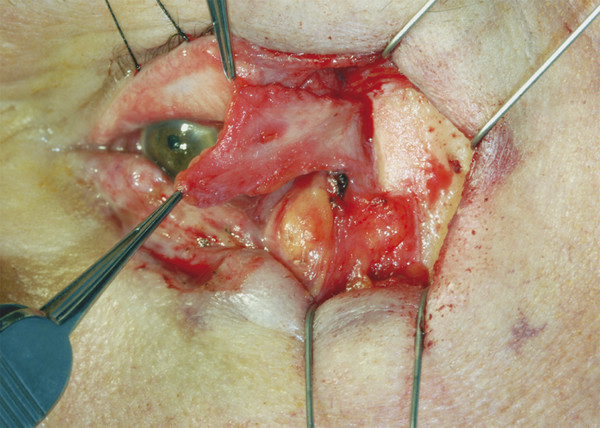

Next, the inferior cantholysis is performed by cutting the tissue between the conjunctiva and the skin using blunt-tipped curved Westcott scissors close to the periosteum of the lateral orbital margin with the lateral lid margin drawn up and medially (Fig. 12‑3). The eyelid will “give” as the inferior crus of the lateral canthal tendon and the orbital septum are severed.

The wound is closed with simple interrupted 6–0 black silk sutures.

Postoperative Care

The postoperative care is the same as described for small defects.

12.4.4 Semicircular Rotation Flap

A semicircular rotation flap (Tenzel flap) is useful for the reconstruction of defects of up to 70% of the lower eyelid in which some tarsus remains on either side of the defect, particularly if the patient’s fellow eye has poor vision. Under these circumstances, it is preferable to avoid a procedure that necessitates closure of the eye for a period of several weeks (e.g., a Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap procedure).

Surgical Procedure

A semicircular incision is marked out with gentian violet starting at the lateral canthus, curving superiorly to a level just below the brow and temporally for approximately 2 cm.

The skin incision is made using a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade.

The flap is then widely undermined using blunt-tipped Westcott scissors to the depth of the superficial temporalis fascia, taking care not to damage the temporal branch of the facial nerve that crosses the midportion of the zygomatic arch (Fig. 2‑40 and Fig. 2‑41).

A lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis are then performed and the eyelid defect is closed as described for small defects.

The lateral canthus is suspended with a deep 5–0 Vicryl suture passed through the periosteum of the lateral orbital margin to prevent retraction of the flap (Fig. 12‑4).

Any residual “dog-ear” is removed and the lateral skin wound closed with simple interrupted 6–0 black silk sutures.

The conjunctiva of the inferolateral fornix is gently mobilized and sutured to the edge of the flap with interrupted 8–0 Vicryl sutures.

Postoperative Care

The postoperative care is the same as described for small defects.

12.4.5 Large Defects

Upper Lid Tarsoconjunctival Pedicle Flap

First Stage

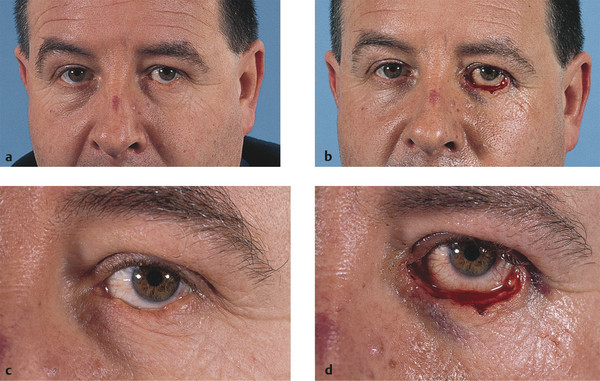

The upper lid tarsoconjunctival pedicle flap (Hughes flap) is an excellent technique for the reconstruction of relatively shallow lower eyelid defects involving up to 100% of the eyelid (Fig. 12‑5). With defects extending horizontally beyond the eyelids, it can be combined with local periosteal flaps to re-create medial or lateral canthal tendons.

Key Point

Great care should be taken in the planning and construction of the tarsoconjunctival pedicle flap to avoid compromising the function of the upper eyelid. It is essential that the patient can cope with occlusion of the eye for a period of 3 to 10 weeks.

Surgical Procedure

The size of the flap to be constructed is ascertained by pulling the edges of the eyelid wound toward each other with a moderate degree of tension using two pairs of Paufique forceps and measuring the residual defect.

A 4–0 silk traction suture is passed through the gray line of the upper eyelid, which is everted over a Desmarres retractor.

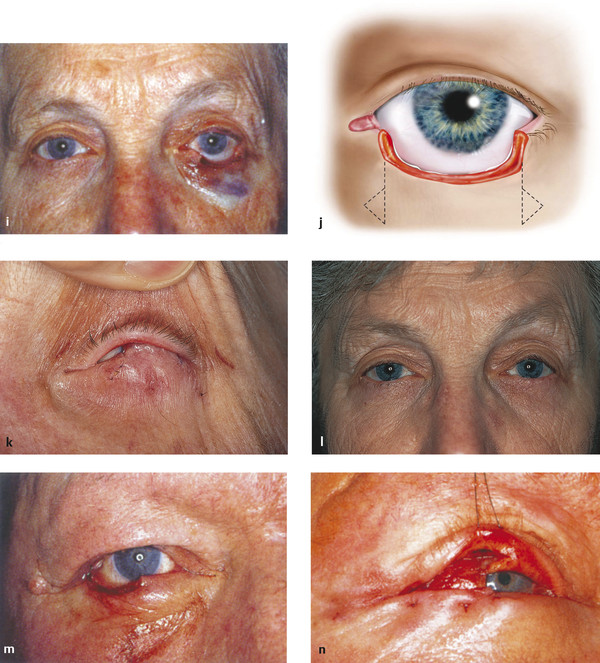

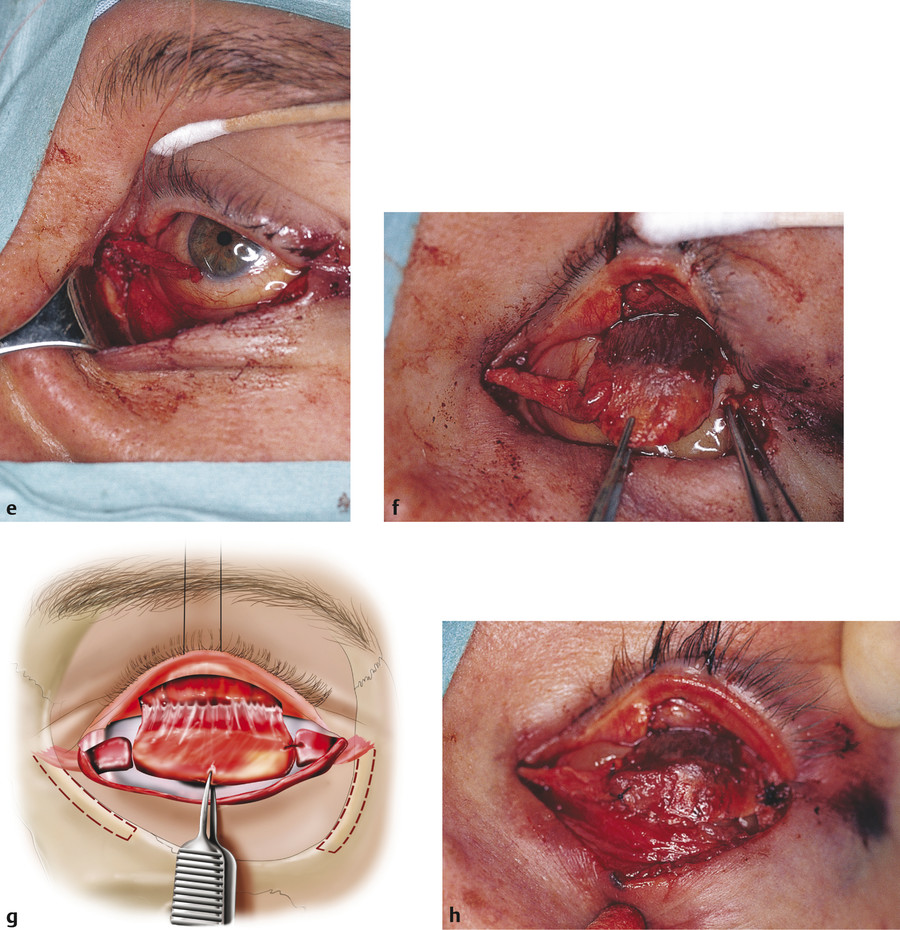

The tarsal conjunctiva is dried with a swab and a series of points, 3.5 mm above the lid margin, are marked with gentian violet (Fig. 12‑6a). These points are then joined to mark an incision line.

A superficial horizontal incision is made centrally along the tarsus 3.5 mm above the lid margin using a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade (Fig. 12‑6b). It is important to leave a tarsal height of 3.5 mm below the incision to maintain the structural integrity of the eyelid and prevent an upper eyelid entropion and to prevent any compromise of the blood supply of the eyelid margin.

The incision is deepened through the full thickness of the tarsus centrally using the no. 15 blade, and the horizontal incision is completed with blunt-tipped Westcott scissors. Vertical relieving cuts are then made at both ends of the tarsal incision (Fig. 12‑6c,d).

The tarsoconjunctival–Müller’s muscle flap is dissected from the levator aponeurosis (Fig. 12‑6e). The tarsus and conjunctiva are dissected free from Müller’s muscle (Fig. 12‑6f,g) and the levator aponeurosis up to the superior fornix. The tarsoconjunctival flap is mobilized into the lower lid defect (Fig. 12‑6g).

The tarsus is sutured, edge to edge, to the lower lid tarsus with interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures, taking great care to ensure that the sutures are passed though the tarsus in a partial-thickness fashion (Fig. 12‑6h). The lower lid conjunctival edge is sutured to the inferior border of the mobilized tarsus with interrupted 7–0 Vicryl sutures.

Sufficient skin to cover the anterior surface of the flap can often be obtained by advancing a myocutaneous flap from the cheek (Fig. 12‑6i–l). This flap can be elevated by bluntly dissecting a skin and muscle flap inferiorly toward the orbital rim.

The lid and cheek skin are incised vertically at the medial and lateral borders of the flap using straight iris scissors.

Relaxing triangles (Burow’s triangles) may be excised on the inferior medial and lateral edges of the defect to avoid dog-ears (Fig. 12‑6j).

The skin–muscle flap is then advanced after sufficient undermining so that it will lie in place without tension.

This flap is then sutured into place with its upper border at the appropriate level to produce the new lower lid margin. Two interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures are passed through the flap and anchored to the tarsus using a partial-thickness pass of the needle (Fig. 12‑6m,n).

The skin edges are sutured to the superior aspect of the tarsus using interrupted 7–0 Vicryl sutures.

Topical antibiotic ointment is instilled into the eye and the eye closed.

A Jelonet dressing is placed over the eye, followed by two eye pads and a firm compressive bandage to prevent excessive swelling. If a full-thickness skin graft has been used, an additional piece of Jelonet is folded to fit over the skin graft, and the same occlusive dressing is applied for 4 days.

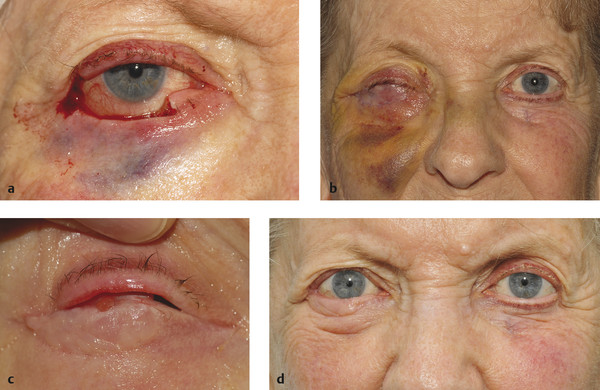

For a patient with relatively tight, nonelastic skin, such an advancement flap may eventually lead to eyelid retraction or an ectropion when the flap is separated (Fig. 12‑11a,b). In such cases, it is wiser to use a free full-thickness skin graft from the opposite upper lid, preauricular area, retroauricular area, or the upper inner arm. The graft should not usually be taken from the upper lid of the same eye as the Hughes flap unless there is a lot of redundant skin, because the resultant vertical shortening of both the anterior and the posterior lamellae may produce vertical contracture of the donor lid. The skin graft should be thinned meticulously and sutured into place with interrupted 7–0 Vicryl sutures. The graft should fit the defect perfectly and should be sutured under a slight degree of tension (Fig. 12‑7).

If possible, a “bucket handle” flap of orbicularis muscle can be advanced after dissecting it free from the overlying skin below the defect. This is then sutured to the superior border of the tarsus with interrupted 7–0 Vicryl sutures. This flap will improve the vascularity of the recipient bed for the skin graft and will help to enhance the resultant cosmetic appearance (Fig. 12‑8).

Postoperative Care

The dressing is removed after 48 hours. If a full-thickness skin graft has been used, the dressing is not removed for 4 days. The Vicryl sutures are all removed after 2 weeks. The patient is instructed to keep the reconstructed eyelid clean and free of desquamated skin and debris by lifting the upper lid and by gently cleaning the area with cotton-tipped applicators moistened with cool boiled water three times a day. Topical antibiotic is applied to the wounds three times a day for 2 weeks.

If a full-thickness skin graft has been used, the patient is instructed to massage the skin graft in an upward and horizontal direction for a few minutes three to four times per day using a preservative-free lubricant eye ointment. A silicone preparation, such as Kelocote or Dermatix, can also be applied after a few days to help to reduce contracture. The massage is commenced 2 weeks postoperatively. This should be continued for 4 to 6 weeks. If the skin graft thickens, it can be injected with a total of 0.2 to 0.4 ml of triamcinolone at several different points and the massage continued.

Second Stage

The flap can be opened approximately 3 to 10 weeks (or longer if necessary) after surgery. If a skin graft has been used it is preferable to ensure that the graft is supple and unlikely to contract further before the flap is opened to prevent retraction of reconstructed lower eyelid. If the procedure is undertaken under local anesthesia, it is preferable to use intravenous sedation, because the administration of local anesthesia can be particularly uncomfortable for such patients.

Surgical Procedure

Two to three milliliters of 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 units of adrenaline mixed 50:50 with 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 units of adrenaline are injected subcutaneously into the upper and lower eyelids. If a skin graft was previously used it is preferable to commence with an infraorbital nerve block.

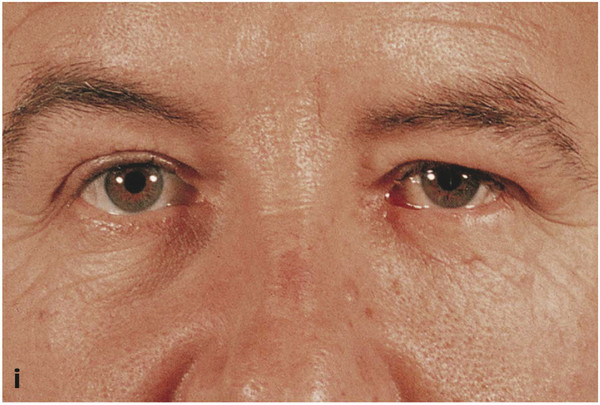

Next, one blade of a pair of blunt-tipped straight Westcott scissors is inserted just above the desired level of the new lid border and the flap is cut open. It is unnecessary to angle the scissors to leave the conjunctival edge somewhat higher than the anterior skin edge. Traditionally, this provided some conjunctiva posteriorly to be draped forward to create a new mucocutaneous lid margin, but this leaves a reddened lid margin, which is cosmetically poor. It is preferable to simply divide the flap where the lid margin should be and to allow the lid margin to simply granulate (Fig. 12‑9a). Hot wire cautery or bipolar cautery can be applied to any irregularities in the lid margin. The resultant appearance is far better (Fig. 12‑9b).

The upper lid is then everted and the residual flap is excised flush with its attachment to the upper lid tarsus using blunt-tipped Westcott scissors. (If Müller’s muscle has been left undisturbed in the original dissection of the flap, eyelid retraction is minimal and no formal attempt is needed to recess the upper lid retractors.)

Postoperative Care

The patient is instructed to keep the eyelid margin meticulously clean and to apply topical antibiotic ointment three times a day for 2 weeks. Topical lubricants should also be prescribed for a few weeks. The Hughes procedure can provide excellent cosmetic and functional results for lower lid reconstruction (Fig. 12‑6i).

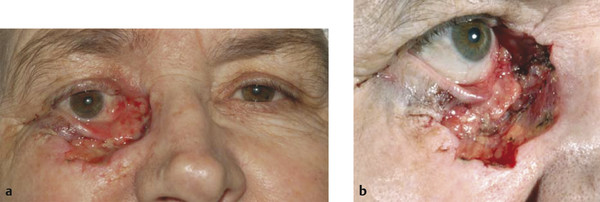

Although the Hughes procedure is traditionally used for the reconstruction of shallow marginal defects of the lower eyelid, it can be used in conjunction with local periosteal flaps for a simplified reconstruction of more extensive defects of the lower lid (Fig. 12‑10). This avoids more invasive procedures and can still be performed under local anesthesia. The term “maximal Hughes procedure” has been coined for this reconstructive technique.

Complications

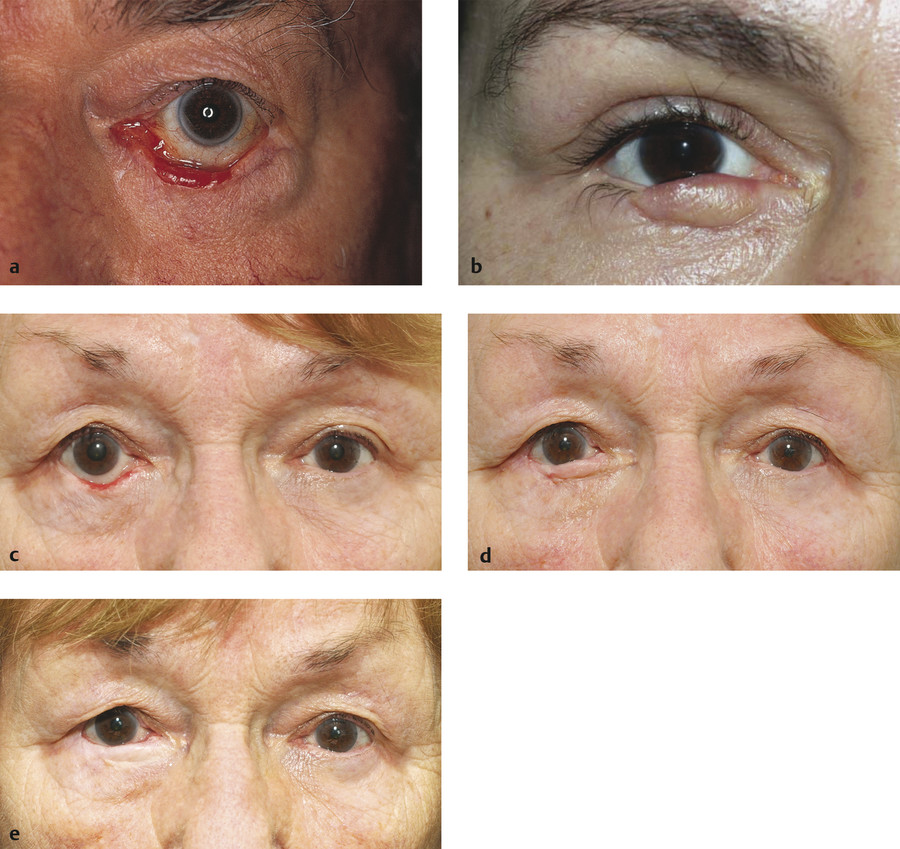

Lower eyelid retraction.

Lower eyelid ectropion.

A reddened eyelid margin.

Upper eyelid retraction.

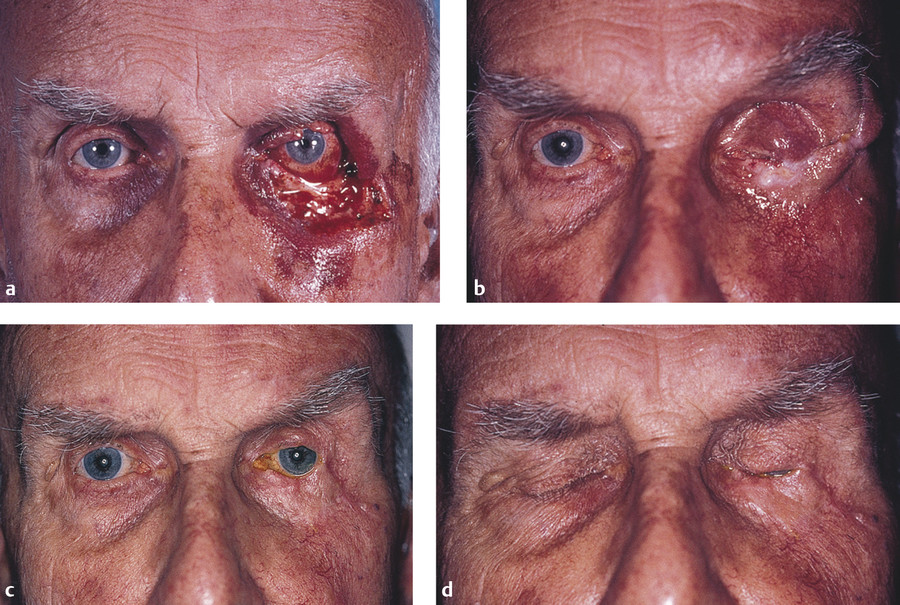

These complications of the Hughes procedure can be avoided if the basic principles outlined previously are closely adhered to (Fig. 12‑11a,b). The lower eyelid will retract if a skin–muscle advancement flap has been used where there is insufficient residual anterior lamella, if the flap has been divided too soon, or if the patient has not applied sufficient postoperative massage. Revision surgery for such patients is difficult and will rarely yield a good cosmetic result (Fig. 12‑11c–e).

An unsightly eyelid margin is avoided by performing a simple division of the flap without formal overlapping or suturing of the conjunctiva, with cautery applied to the new lid margin (Fig. 12‑12).

Some upper eyelid retraction is inevitable but can be kept to a minimal degree by excluding Müller’s muscle from the tarsoconjunctival flap. If an unsatisfactory degree of upper lid retraction does occur, it can be treated using a posterior-approach upper lid retractor recession (Chapter 8).

12.4.6 Periosteal Flaps

For the repair of medial or lateral lid defects in which the tarsus and the lateral or medial canthal tendons have been completely excised, periosteal flaps provide excellent support for the reconstruction.

12.4.7 Lateral Periosteal Flap

Surgical Procedure

A short lateral periosteal flap is created by making two horizontal periosteal incisions over the lateral orbital margin 4 to 5 mm apart with a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade. The uppermost incision is made at the level of the insertion of the lateral aspect of the upper eyelid.

A vertical relieving incision joining the two horizontal incisions is made over the most lateral aspect of the lateral orbital margin.

The flap is then elevated toward the orbit using the sharp-tipped end of a Freer periosteal elevator. The flap is anchored at the junction of the periosteum with the periorbita.

The flap is sutured to the lateral margin of the tarsus of the upper lid tarsoconjunctival flap with interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures.

A longer lateral periosteal flap can be obtained by raising the flap vertically from the lateral orbital margin extending onto the malar eminence. The anchor point, however, remains the same (Fig. 12‑13).

Topical antibiotic ointment is instilled into the eye and the eye closed.

A Jelonet dressing is placed over the eye, followed by two eye pads, and a firm compressive bandage is applied to prevent excessive swelling.

Postoperative Care

This is as described in Upper Lid Tarsoconjunctival Pedicle Flap, Second Stage, Postoperative Care.

12.4.8 Medial Periosteal Flap

Surgical Procedure

A short medial periosteal flap is created by making two horizontal periosteal incisions over the medial orbital margin 4 to 5 mm apart with a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade. The uppermost incision is made at the level of the insertion of the medial aspect of the upper eyelid. A horizontal skin incision may be necessary, extending to the bridge of the nose, to gain access to an adequate length of periosteum.

A vertical relieving incision joining the two horizontal incisions is made over the bridge of the nose.

The flap is then elevated toward the orbit using the sharp-tipped end of a Freer periosteal elevator. The flap is anchored at the junction of the periosteum with the periorbita.

The flap is sutured to the medial margin of the tarsus of the upper lid tarsoconjunctival flap with interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures. Great care needs to be taken, because this periosteal flap tends to be thinner and less robust than a lateral periosteal flap.

Topical antibiotic ointment is instilled into the eye and the eye closed.

A Jelonet dressing is placed over the eye, followed by two eye pads, and a firm compressive bandage is applied to prevent excessive swelling.

The Hughes procedure may be combined with other reconstructive techniques, such as a Fricke flap, to achieve the best result for an individual patient (Fig. 12‑14).

Postoperative Care

This is as described in Upper Lid Tarsoconjunctival Pedicle Flap, Second Stage, Postoperative Care.

12.4.9 Free Tarsoconjunctival Graft

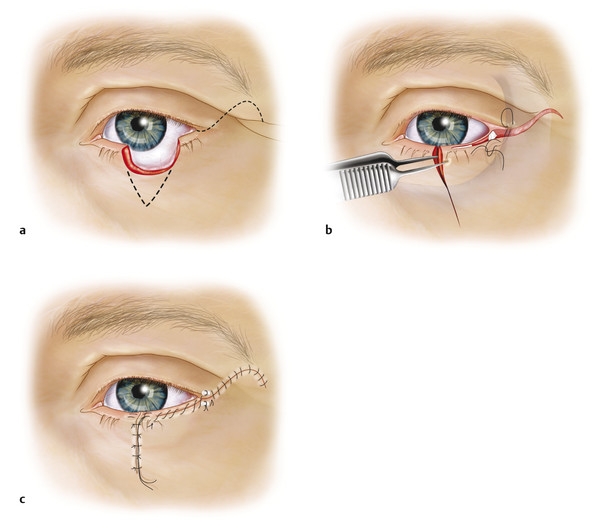

Adequate tarsal support may be provided by harvesting a free tarsoconjunctival graft from either upper lid. The graft must be covered by a local vascularized myocutaneous advancement, rotation, or transposition flap.

This technique is useful for lower eyelid reconstruction in a monocular patient, because it does not occlude the visual axis. If the surgical defect extends to involve the canthal tendons, the free graft should be anchored to periosteal flaps as described previously.

Surgical Procedure

A 4–0 silk traction suture is passed through the gray line of the upper eyelid, which is everted over a Desmarres retractor.

The tarsal conjunctiva is dried with a swab, and a series of points 3.5 mm above the lid margin are marked with gentian violet. These points are then joined to mark an incision line.

The size of the graft required is determined and marked out.

A superficial horizontal incision is made centrally along the tarsus 3.5 mm above the lid margin using a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade. It is important to leave a tarsal height of 3.5 mm below the incision to maintain the structural integrity of the eyelid to prevent an upper eyelid entropion and to prevent any compromise to the blood supply of the eyelid margin.

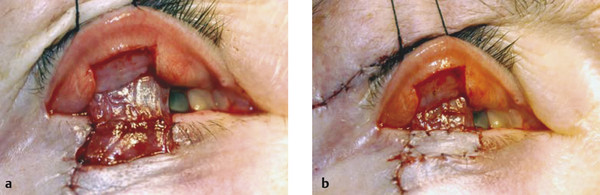

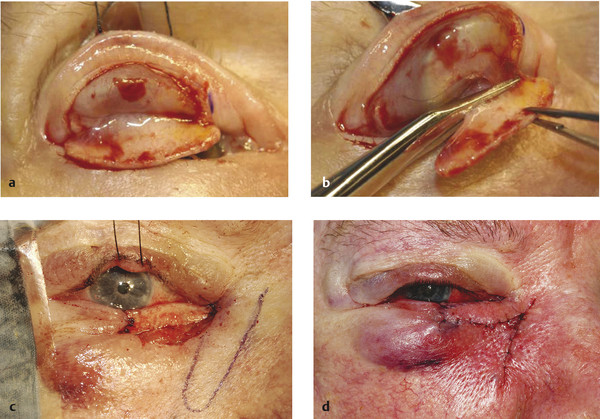

The incision is deepened through the full thickness of the tarsus centrally using the no. 15 blade, and the horizontal incision is completed with blunt-tipped Westcott scissors (Fig. 12‑15a,b).

Vertical relieving cuts are then made at both ends of the tarsal incision.

The tarsal graft is dissected from the underlying tissues and amputated at its base.

The tarsal graft is sutured into the recipient lower lid defect as described previously.

A myocutaneous flap (a rotation, transposition, or advancement flap) is then fashioned to lie over the graft (Fig. 12‑15c–e).

Postoperative Care

This is as described in Upper Lid Tarsoconjunctival Pedicle Flap, Second Stage, Postoperative Care.

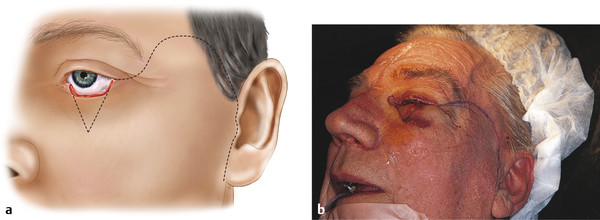

12.4.10 Mustardé Cheek Rotation Flap

With the development and popularity of other reconstruction techniques and with the tissue-conserving advantages of Mohs’ micrographic surgery, the Mustardé cheek rotation flap is used far less than in the past. It is typically reserved for the reconstruction of very extensive deep eyelid defects involving more than 75% of the eyelid.

A large myocutaneous cheek flap is dissected and used in conjunction with an adequate mucosal lining posteriorly. The posterior lamellar tarsal substitute is usually a nasal septal cartilage graft or a hard palate graft. The important points in designing a cheek flap are summarized by Mustardé as follows.

A deep inverted triangle must be excised below the defect to allow adequate rotation (Fig. 12‑16). The side of the triangle nearest to the nose should be practically vertical. Failure to observe this point will result in a pulling down of the advancing flap because the center of rotation of the leading edge is too far to the lateral side.

The outline of the flap should rise in a curve toward the tail of the eyebrow and hairline and should reach down just in front of the ear as far as the lobule of the ear (Fig. 12‑16).

The flap must be adequately undermined from the lowest point of the incision in front of the ear across the whole cheek to within 1 cm below the apex of the excised triangle. Great care must also be exercised to avoid damage to branches of the facial nerve.

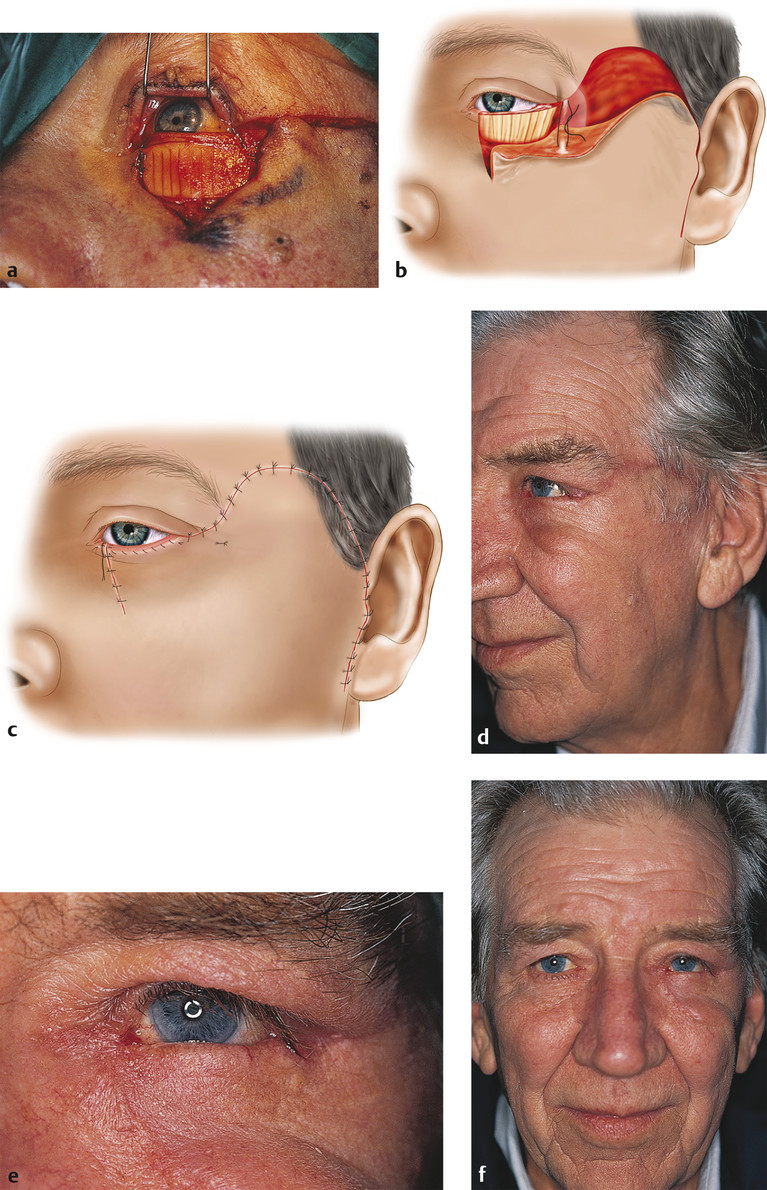

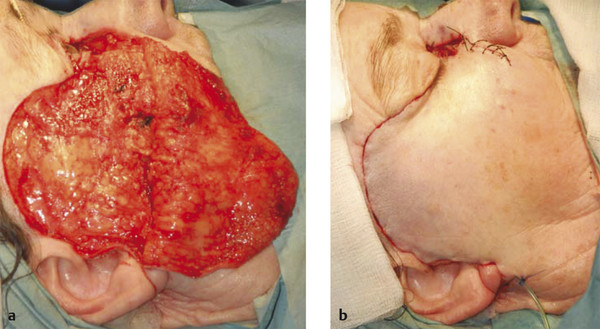

Where necessary (in defects of three-quarters or more), a back cut should be made at the lowest point, 1 cm or more below the lobule of the ear. The deep tissue of the flap should be hitched up to the orbital rim, especially at the lateral canthus, to prevent the weight of the flap from pulling on the lid (Fig. 12‑17). A typical early result after this reconstructive procedure is shown in Fig. 12‑17.

Key Points

Cheek flaps can be followed by many complications, including facial-nerve paralysis, hematoma, necrosis of the flap, ectropion, entropion, epiphora, sagging of the reconstructed lower eyelid (Fig. 12‑18), and excessive facial scarring. It is very important to plan the design of the flap and to appreciate the plane of dissection to avoid inadvertent injury to the facial nerve branches, which can result in lagophthalmos. Meticulous attention to hemostasis is important, as is placement of a drain and a compressive dressing at the conclusion of surgery.

Surgical Procedure

The cheek rotation flap is marked out very carefully with gentian violet. The outline of the flap should rise in a curve toward the tail of the eyebrow and hairline and should reach down just in front of the ear as far as the lobule of the ear (Fig. 12‑16).

The midface is then infiltrated with a tumescent local anaesthetic solution made up of 30mL of saline for injection, 0.25mL of adrenaline 1:1,000, 10mL of 0.25% bupivacaine, and 10 mL of 2% lidocaine made up in a 50mL syringe. The solution is injected using a 20-mL Luer-Lock syringe and a 21-gauge needle. Approximately 15 to 20 mL of the solution are injected subcutaneously over the central and lateral midface, and pressure is then applied to diffuse the solution. The solution is allowed at least 10 minutes to work.

The skin is incised along the gentian violet marks using a no. 15 Bard–Parker blade.

The flap is then undermined in a superficial subcutaneous plane using blunt dissection with blunt-tipped curved Stevens scissors and toothed Adson forceps. The undermining is continued until the flap can be rotated adequately without undue tension.

The deep aspect of the flap is sutured to the periosteum of the lateral orbital margin using a 4–0 PDS suture.

The medial vertical subcutaneous aspect of the flap is closed with interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures.

The lateral subcutaneous aspects of the flap are also closed with interrupted 5–0 Vicryl sutures. A vacuum-assisted drain is placed before the wound closure has been completed. This should be sutured to the adjacent skin to prevent the drain from being inadvertently removed (Fig. 12‑19).

If the lateral preauricular defect cannot be closed directly, it can instead be covered with a full-thickness skin graft.

The medial and lateral skin closure is achieved with interrupted 6–0 Novafil sutures.

The skin is sutured to the posterior lamellar flap or graft using interrupted 7–0 Vicryl sutures.

The wounds should be covered with antibiotic ointment and Jelonet dressings. Eye pads and gauze swabs should be placed over the wounds and the midface, and these should be held in place with a bandage that is applied without excessive tension.

Postoperative Care

The patient should keep the head raised postoperatively and avoid any lifting or straining for a week. The dressings are removed after 48 hours and the drain removed postoperatively as soon as the drainage of any blood has ceased. Topical antibiotic ointment is applied to the wounds for 2 weeks. The skin sutures are removed after 10 to 14 days.

The Mustardé cheek rotation flap may be used for the reconstruction of a defect that extends to involve the medial canthus and can be used in combination with other local tissue flaps or laissez-faire (healing by secondary intention)(Fig. 12‑20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree