Congenital Onset of Primary Lymphoedema

Milroy disease (OMIM 153100)

Milroy disease was first described in a nine-generation family in 1892 by a US physician and is defined as congenital, familial lymphoedema [9,10].

Aetiology.

Milroy disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition, with an equal gender incidence, but there is variable expression and penetrance of the disorder [11]. By collecting large pedigrees with Milroy disease and carrying out linkage studies, the gene for this condition has been localized to chromosome 5q35 and identified as FLT4 (VEGFR3) [12,13]. The mutations have been identified mainly as missense mutations encoding proteins with an inactive tyrosine kinase, preventing activation of downstream genes and a subsequent failure of lymphangiogenesis.

Clinical Features.

The term Milroy disease is often applied loosely to many different types of lymphoedema, but Milroy disease as a cause of lymphoedema is rare if the correct criteria for diagnosis are applied. Clinically, affected individuals present at birth with swelling of both lower limbs, particularly the dorsum of the feet, which is firm, woody and difficult to pit. The nails are small, dysplastic and upturned, with deep creases over the toes (Fig. 114.2). The oedema is normally confined to below the knees and may be asymmetrical. The swelling may improve, remain stable or worsen with time. Many of the affected males also have hydroceles but there do not appear to be any other abnormalities associated with this condition.

Investigations.

Previous studies [14,15] have demonstrated that this disease is due to hypoplasia or aplasia of the lymphatics in the lower limbs, suggesting that the primary defect is a congenital deficiency of the lymphatics. Skin lymphatics are reportedly absent as in the mouse model, but recent work in humans with a confirmed mutation has demonstrated that lymphatic vessels are present but are non-functional [16]. Furthermore 50% of mutation carriers have superficial venous reflux.

Primary Lymphoedema with Later Onset

Meige disease (OMIM 153200)

In 1898, Meige described a family with lymphoedema appearing at puberty [17]. The eponym Meige disease is now associated with primary lymphoedema with onset in adolescence or adulthood. This condition is believed to affect females three times more often than males. Only 30% have a family history but when present it is an autosomal dominant form of primary lymphoedema. The lymphoedema is confined to the lower limbs, rarely above the knees and usually bilateral (Fig. 114.3). This condition is thought to be due to hypoplasia of the peripheral superficial lymphatic collecting vessels [18]. It may even be due to a peripheral lymphatic occlusion rather than a true congenital hypoplasia or aplasia [19]. There are no other features or congenital abnormalities associated with this condition. Again, there is a variable degree of expression, with some family members being more affected than others.

Much work has been carried out in an attempt to localize the gene for this condition; however, there may be genetic heterogeneity, making linkage difficult. To date the gene or genes for this condition have not been identified.

Lymphoedema–Distichiasis Syndrome (MIM 153400)

Lymphoedema–distichiasis (LD) syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition that has been well characterized. Although this condition was initially thought to be very rare, more than 18 families have been identified in the UK alone [20].

Aetiology.

Genetic studies have shown linkage to chromosome 16q [21], and mutations in the gene FOXC2 have been identified in association with this condition [22].

FOXC2 (MFH1) is a forkhead transcription factor gene. Analysis of 18 families and six sporadic cases of lymphoedema–distichiasis syndrome demonstrated that all but one family had small insertions or deletions in FOXC2, which are likely to cause loss-of-function and result in haploinsufficiency [20,23]. There was no obvious genotype–phenotype correlation. Inactivation of Foxc2 in both alleles in the mouse results in aortic arch, skeletal, genitourinary and cardiac malformations, and leads to embryonic and perinatal lethality. Abnormal lymphatic vascular patterning has been demonstrated in these mice, with increased pericyte investment of lymphatic vessels, agenesis of valves and lymphatic dysfunction. Skin biopsies from patients with a heterozygous FOXC2 mutation showed that an abnormally large proportion of skin initial lymphatic vessels were covered with smooth muscle cells in individuals with LD (in the lower but not the upper limbs) and in mice heterozygous for Foxc2. FOXC2 is, therefore, essential for the morphogenesis of lymphatic valves and the establishment of a lymphatic capillary free of smooth muscle [24].

Clinical Features.

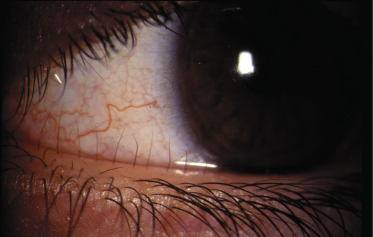

The lymphoedema in this condition is frequently associated with distichiasis. Distichiasis is translated (from the Greek) as a double row of eyelashes; however, they rarely present as such and usually present as aberrant eyelashes arising from the Meibomian glands in the inner eyelids. The distichiasis is nearly always present from birth, and affected individuals may be unaware of their presence; it is important therefore to examine the individual carefully as the aberrant eyelashes can often be seen with the naked eye (Fig. 114.4). In most cases these eyelashes cause irritation, photophobia, recurrent conjunctivitis and styes.

The lymphoedema presents in late childhood, puberty or adulthood. It appears to have an earlier onset and is more severe in males. Again, expression is variable in this condition and a minority of gene carriers do not develop lymphoedema (5%). In women, the oral contraceptive pill or pregnancy may precipitate the swelling.

This particular cause of primary lymphoedema is strongly associated with varicose veins. In one study 100% of affected patients with a FOXC2 mutation and lymphoedema as well as carriers unaffected by lymphoedema had superficial venous reflux. Fifty percent had deep venous reflux [25]. These cases usually occurred at a much younger age than in the general population and in some cases required surgery. This association is not very surprising as the development of the lymphatics is closely related to the development of the venous system (as previously discussed) and the veins are reliant on the normal function of their valves to prevent retrograde flow.

A number of other congenital abnormalities may be associated with this condition, such as ptosis (35%), congenital heart disease (8%) and cleft palate (3%).

Investigations.

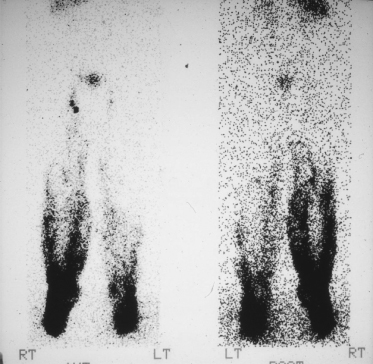

Unlike Meige syndrome, lymphangiograms have demonstrated that there is no hypoplasia of the lymphatic vessels; in fact the number of vessels is frequently increased with an increased number of inguinal lymph nodes. Lymphoscintigraphy often demonstrates reflux of the lymph into the lower aspect of the legs (Fig. 114.5).

Fig. 114.5 Lymphoscintigram of patient with lymphoedema–distichiasis, showing reflux of tracer back down into the lower leg.

Reproduced from Brice et al. 2002 [20] with permission from the BMJ.

Primary Lymphoedema As a Feature of Other Syndromes

An increasing number of syndromes are being identified as associated with primary lymphoedema. In some of these the underlying gene has been identified. Presumably these genes have a role in the development of the lymphatic system, therefore learning about these genes will help to clarify the embryology of the lymphatic system and lead to greater understanding of the disorders of the lymphatics. It is important to recognize these disorders in order to identify associated abnormalities.

Turner Syndrome

Turner syndrome (see also Chapter 116) is defined as gonadal dysgenesis due to either an absent or a structurally defective X chromosome [26]. It was originally described in six girls by Turner [27] in 1938. The frequency of Turner syndrome is 1 per 2500 female births [28].

Aetiology.

This condition is due to the absence or partial absence of a sex chromosome [29]. The karyotype in this condition is usually 45,XO; however, there are many affected individuals with partial absence of one of the X chromosomes or the Y chromosome or even a ring chromosome X. Many have a mosaic karyotype with some cells being normal female (46XX), or even having triple X (three X chromosomes) in some cells, suggesting a postzygotic abnormality. There are reported males with Turner’s syndrome who are mosaic for normal male cells (46,XY/45,XO).

Over 95% of fetuses with 45,XO miscarry in the first or second trimester, particularly if the abnormality is associated with hydrops fetalis. This condition is frequently associated with a cystic hygroma or increased nuchal translucency on the 11- to 13-week antenatal ultrasound scan [30,32].

Clinical Features.

The main features associated with Turner syndrome are short stature and infertility. There are ovarian streaks instead of properly formed gonads. There may be congenital abnormalities such as renal abnormalities (particularly horseshoe kidney) and congenital heart disease (especially coarctation of the aorta). Intelligence is usually within the normal range.

Turner syndrome in most cases is associated with an abnormality of the lymphatic system. Affected females frequently have oedema of the dorsum of their feet. This appears to improve with time and is rarely severe. Lymphangiography has demonstrated hypoplasia of the lymphatic vessels in the lower extremities [31]. Other abnormalities in this condition that suggest a lymphatic disorder are the association with increased nuchal oedema (discussed later), webbed neck, low hairline and epicanthic fold, all of which are believed to be associated with oedema in utero [30]. These features all suggest either an abnormality or a delayed maturation of the lymphatic system. However, no specific gene for lymphoedema has been identified on the X chromosome [33]. The clinical features may suggest the diagnosis in infancy; however, if they are subtle, the diagnosis may be missed until puberty, when they may present with primary amenorrhoea or absent secondary sexual characteristics.

Noonan Syndrome (OMIM 163950)

Aetiology.

Noonan syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition [34,35] with a high incidence of new sporadic mutations, so there is not always a family history of the condition. It affects males and females equally, and has some features in common with Turner syndrome. Noonan syndrome is due to mutations in a number of genes in the RAS-MAP kinase pathway including PTPN11, kRAS, and SOS1 [36–38].

Clinical Features.

It is characterized by short stature, mild to moderate learning difficulties and congenital heart disease, particularly pulmonary stenosis or cardiomyopathy. There are some typical dysmorphic features, with downslanting of the palpebral fissures, ptosis, epicanthic folds, low-set posteriorly rotated ears, webbed neck and low hairline.

Noonan syndrome is associated with various forms of lymphatic disorders. It may present in utero with an increased nuchal translucency or hydrops fetalis. There may be lymphoedema of the lower limbs, which can present at birth or later in childhood. Intestinal lymphangiectasia and pulmonary lymphangiectasia have also been reported in children with this condition [39]. Studies of the lymphatics with lymphangiography have shown a variety of abnormalities in patients with Noonan syndrome, including aplasia, hypoplasia and lymphangiectasia [40,41].

Osteopetrosis, Lymphoedema, Ectodermal Dysplasia Anhydrotic and Immune Deficiency Syndrome (OMIM 308300)

The OL-EDA-ID (osteopetrosis, lymphoedema, ectodermal dysplasia anhydrotic and immune deficiency) syndrome is a rare condition in males caused by hypomorphic mutations in the IKBKG (previously known as NEMO Nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B Essential MOdulator]) gene [42]. The lymphoedema is usually of the lower limbs. One patient was shown by lymphoscintigraphy to have a lymphatic obstruction. The MRI on this patient suggested a lymphangiomatous malformation [43].

Cholestasis–Lymphoedema Syndrome (Aagenaes Syndrome) (OMIM 214900)

Aetiology.

The association of cholestasis with congenital lymphoedema was first described in two Norwegian pedigrees by Aagenaes and colleagues in 1968 [44]. Consanguinity of the parents and recurrence in siblings are frequently reported in this condition, suggesting autosomal recessive inheritance. The gene is still unknown but is located on chromosome 15q [45].

Clinical Features.

Jaundice presents shortly after birth and recurs intermittently. Lymphoedema of the lower limbs presents at about 5 or 6 years and is progressive. There is a high mortality in this condition as the liver develops fibrosis and cirrhosis in later childhood [46].

Microcephaly–Lymphoedema–Chorioretinal Dysplasia (OMIM 152950)

Crowe and Dickerman [47] first described this very rare autosomal dominant disorder in 1986. They described a male and his maternal uncle with microcephaly and peripheral lymphoedema. Other members of the family also had lymphoedema.

Jarmas and colleagues [48] described microcephaly and lymphoedema in association with falciform retinal folds. Reports since then have confirmed the presence of chorioretinopathy in these families.

Vasudevan et al. [49] described three further cases with specific dysmorphic features, microcephaly and eye abnormalities. The degree of learning difficulties is frequently mild in this condition. The lymphoedema is predominantly of the dorsum of the feet and present at birth. The characteristics of the oedema are very similar to Milroy disease. The genetic cause and mode of inheritance of this condition have not yet been identified.

Hypotrichosis–Lymphoedema–Telangiectasia (OMIM 607823)

This rare condition is caused by autosomal dominant or recessive mutations in the gene SOX18. Mutations in this gene were first identified in the ‘ragged’ phenotype mouse characterized by hair and cardiovascular anomalies and symptoms of lymphatic dysfunction (chylous ascites). Patients with this condition may present with lymphoedema at birth or during childhood. The swelling is usually of the lower limbs. There is a progressive alopecia of scalp hair, eyebrows and eyelashes. Telangiectasia may be present on the palms and or soles [50].

Lymphoedema–Myelodysplasia (Emberger Syndrome)

A small number of reports have been published on an association between myelodysplasia, acute myeloid leukaemia and primary lymphoedema, with or without congenital deafness. The lymphoedema typically presents in one or both lower limbs, before the haematological abnormalities, with onset between infancy and puberty, and frequently affects the genitalia. The acute myeloid leukaemia is often preceded by pancytopenia or myelodysplasia with a high incidence of monosomy 7 in the bone marrow. Associated anomalies included hypotelorism, epicanthic folds, long tapering fingers and/or neck webbing, recurrent cellulitis in the affected limb, generalized warts and congenital, high-frequency sensorineural deafness. Family studies suggest that this is an autosomal dominant condition, but the genetic basis for this condition is still unknown [51–53].

Generalized Lymphatic Dysplasia

Generalized Lymphatic Dysplasia (Hennekam Syndrome) (OMIM 235510)

Aetiology.

Hennekam first described this condition in 1989. Recurrence in siblings and affected offspring from consanguineous marriages has been reported suggesting autosomal recessive inheritance [54]. One of the genes for this condition has recently been identified as collagen and calcium-binding EGF domain-1 (CCBE1) [55,56]. Mutations in the ccbe1 gene in the zebra fish result in an oedematous embryo (fof – full of fluid), and this has been shown to be due to abnormalities in early lymphangiogenesis. This gene is crucial for lymphangioblast budding and angiogenic sprouting from venous endothelium [57].

Mutations have been identified in 7 of 22 probands suggesting genetic heterogeneity in this condition [56].

Clinical Features.

The affected child has widespread disorder of the lymphatic system, with visceral involvement (particularly intestinal lymphangiectasia) and lymphoedema of the limbs, genitalia and face (Fig. 114.6). There may be learning difficulties, epilepsy and microcephaly, although milder cases with normal intelligence have been reported. The dysmorphic features are consistent with oedema in utero, with epicanthic folds, flat nasal bridge, thickened, oedematous eyelids and downslanting palpebral fissures. The neck may be webbed [55]. The oedema is usually generalized but may be asymmetrical. It may present antenatally with hydrops fetalis, at birth or at any time in the first 12 years of childhood. There is a high prenatal and postnatal mortality associated with this condition.

Generalized, Multisegmental Lymphatic Dysplasia

This condition presents with a mosaic of lymphoedema affecting different body parts, in a segmental, asymmetrical pattern, with visceral involvement and a low recurrence risk. Facial involvement is frequent. Visceral or systemic involvement includes pleural or pericardial effusions, and pulmonary or intestinal lymphangiectasia. This condition usually presents at birth and there is rarely a significant family history. The aetiology is unknown [8].

Lymphoedema with Overgrowth, Vascular or Cutaneous Manifestations and Congenital Multisegmental Lymphoedema

This is a diverse group of patients with vascular anomalies, disturbed limb growth (overgrowth or undergrowth) and/or cutaneous manifestations, of varying types, with or without lymphoedema.

Lymphatic abnormalities can be seen as a component of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), Parkes Weber syndrome, Proteus syndrome and CLOVE (Congenital Lipomatous Overgrowth, Vascular malformations and Epidermal naevi) syndrome. These are distinct congenital malformation entities about which there is much literature and debate attempting to delineate the diagnostic criteria.

Aetiology.

The aetiology of these conditions remains unknown and the severity of the phenotype is highly variable. However, the sibling and offspring recurrence risk is very low suggesting that they are not due to a germline mutation. There have been various speculations as to the underlying cause, but the mechanism is still not understood.

Clinical Features.

Klippel–Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS) (OMIM 149000) [58]

Oduber et al. [59] proposed the following definition for KTS: KTS is characterized by two major features (at least one from group a, which should always include either a1 or a2, and at least one from group b):

Group a: Congenital vascular malformations

1 Capillary malformation including port-wine stains on any part of the body.

2 Venous malformation including hypoplasia or aplasia of veins, persistence of fetal veins, varicosities, hypertrophy, tortuosity, and valvular malformations.

3 Arteriovenous malformations (AVM): this includes only very small AVMs or arteriovenous fistulae.

4 Lymphatic malformations: including hypoplasia, hyperplasia of the lymphatics or megalymphatics.

Group b: Disturbed growth

1 Disturbed growth of bone in the length or girth.

2 Disturbed growth of soft tissue in the length or girth.

The disturbed growth includes hypertrophy or hypotrophy of a limb or digit and not always at the same site as the capillary or venous malformation.

Elongation of the affected limb is frequently found, whereas lymphoedema occurs in some 84%, varicose veins in 36% and flat capillary malformations (angiomas) in 32%. Deep and superficial veins are malformed. Lymphatic malformations, for example lymphangiomas, may also occur [60]. Thromboembolic episodes and thrombophlebitis frequently occur [61].

Parkes Weber syndrome (OMIM 608355) is a distinct entity associated with significant arteriovenous anastomoses in a limb [62]. Although the term Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome has been used to describe both conditions, they should be considered as separate entities. The distinction between these two entities may be complicated further as some unique features may not become apparent until the patient is older.

Treatment.

Treatment for this condition is mainly conservative. Conventional stripping of varicose veins should not be undertaken unless the deep veins are normal; in KTS this is often not the case. The lymphoedema should be managed in the standard way as specified later. The vascular anomaly is now amenable to treatment using the pulsed dye laser.

Proteus Syndrome (OMIM 176920)

See also Chapter 111.

Aetiology.

This very rare syndrome causes many varied abnormalities (protean manifestations). It has been considered to be a genetic condition for some time, but not inherited. Mutations in the PTEN gene have been reported in Proteus-like syndromes [63], but are not found in most cases of Proteus syndrome and probably represent a distinct sub-phenotype. (PTEN mutations can also cause other hereditary hamartoma syndromes such as Cowden syndrome and Bannayan–Riley–Rulvalcaba syndrome.)

Clinical Features.

Massive, asymmetrical overgrowth of any part of the body, including the face, is characteristic of this condition. There may be macrodactyly with rugose or cerebriform overgrowth of the plantar or palmar soft tissue (moccasin lesion). The overgrown limb may have lymphoedema or lymphatic malformation. Skin manifestations include verrucous epidermal naevi, haemangiomas, varicosities, lipoma-like hamartomas and lymphangiomatous swelling. There may be brain involvement, with hydrocephalus or hemimegancephaly. In some cases there is early death due to pulmonary embolus, laryngospasm, epilepsy or sepsis (for a more detailed review of Proteus syndrome, see Chapter 111).

CLOVE Syndrome (OMIM 612918)

CLOVE syndrome was first described in 2007 [64]. It is characterized by Congenital Lipomatous Overgrowth, Vascular malformations and Epidermal naevi. It appears to be sporadic with a low recurrence rate. The clinical features overlap with Proteus syndrome but patients with this condition have a progressive, complex mixed truncal vascular malformation, dysregulated adipose tissue, vascular malformations and bony overgrowth that, unlike Proteus syndrome, is not progressive. The cerebriform overgrowth of the plantar or palmar soft tissue (moccasin lesion) seen in Proteus syndrome is not seen in this condition.

WILD Syndrome

There are two cases in the literature for whom the acronym WILD syndrome has been proposed; the characteristics are Warts, Immunodeficiency, Lymphoedema and Dysplasia (anogenital). In 2008 Kreuter et al. [65] reported a patient with primary lymphoedema, disseminated flat warts, condylomata acuminata, dysplasia of the genital and anal mucosa, and lymphopenia with severe reversal of the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio. Ostrow et al. [66] reported on a single case with congenital lymphatic dysplasia resulting in lymphoedema, widespread flat warts, compromised T-cell status and condylomatous (partially dysplastic) lesions. The patient developed squamous cell carcinoma of the right thumb and groin [66]. No genetic loci have yet been implicated in WILD syndrome.

Yellow Nail Syndrome (OMIM 153300)

Aetiology.

This is very unlikely to be a genetic condition as there is usually no family history of note [67] However, there have been two case reports describing autosomal dominant inheritance [68]. The diagnosis in these two cases may be inaccurate as discoloration of the nails is frequently associated with lymphoedema.

Clinical Features.

Lymphoedema may present as part of this condition but rarely in children. Lymphoedema is associated with yellow nails, chronic sinusitis and pleural effusions. In most cases the lymphoedema is unusual in that there may be no characteristic skin changes, the oedema can resolve (as can the nails) and there may be only minimal lymphatic insufficiency on lymphoscintigraphy. It is sometimes seen as a paraneoplastic association.

Amniotic Bands

Congenital lymphoedema associated with amniotic bands is poorly understood. The bands, which it is thought may wrap around digits or limbs, cause circumferential fibrosis and scarring. This can lead to autoamputation of digits or lymphoedema distal to the band [69].

Secondary Lymphoedema in Childhood

Damage to the lymphatic channels may occur secondary to any number of causes. Typically, secondary lymphoedema is uncommon in children but it may occur as a result of surgical removal or radiation of lymph nodes for cancer treatment. Cancers that can result in lower limb swelling include sarcoma and pelvic tumours. Lymphoproliferative tumours rarely cause lymphatic obstruction.

Trauma to the lymphatics may lead to lymphoedema. However, extensive trauma is needed to induce permanent lymphoedema due to the efficient regenerative powers of the lymphatics. This regeneration is impeded following scarring.

Filariasis is considered to be the most common cause of secondary lymphoedema worldwide. The infection is often acquired in childhood, and children as young as 3-years old have been shown to be affected. It occurs as a result of infection with the nematode worm (Wuchereria bancroftii), which is transmitted by the mosquito through direct inoculation of the skin with microfilariae. These larvae migrate and mature in the lymphatics into adult worms, leading to progressive damage to these vessels and ultimately causing lymphoedema. However, this is a very rare cause of lymphoedema in the Western world.

Management of Lymphoedema

Diagnosis

Lymphoedema has three main consequences:

1 swelling (oedema);

2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree