- Dysregulated adipose tissue – either one of:

- Lipomas

- Regional absence of fat

- Lipomas

- Vascular malformations – one or more of:

- Capillary malformation

- Venous malformation

- Lymphatic malformation

- Capillary malformation

- Lung cysts

- Facial phenotype consisting of:

- Dolichocephaly

- Long face

- Minor downslanting of palpebral fissures and/or minor ptosis

- Low nasal bridge

- Wide or anteverted nares

- Open mouth at rest

- Dolichocephaly

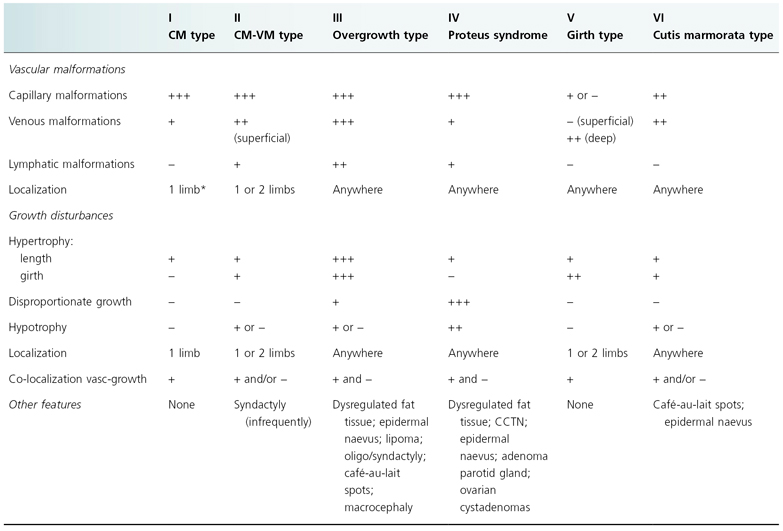

Table 111.1 Proposed classification for Vascular Malformations–Dysregulated Growth syndromes

[5]

CM, capillary malformation; CM-VM, capillary malformation–venous malformation; CCTN, cerebriform connective tissue naevus.

History.

The name of this syndrome comes from the Greek god Proteus, ‘the polymorphous’, who could change shape at will to avoid capture. The name reflects the highly variable manifestation of this disorder. Wiedemann and colleagues [6] who named it were unaware that this syndrome had already been described.

Cohen and Hayden [7] in 1979 first delineated this syndrome as ‘a newly recognized hamartomatous syndrome’. They reported two children with hamartomatous overgrowth, who were believed to have had neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) for many years. In this report they differentiated this new syndrome from NF1 and Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome.

Joseph Carey Merrick, the ‘Elephant Man’, probably had Proteus syndrome and not neurofibromatosis as previously thought [8]. His remains have been kept and studied at the Royal London Hospital in London (UK). The skeletal findings are consistent with Proteus syndrome, with ‘moccasin’ lesions and the absence of café-au-lait spots [8].

To date, more than 100 cases have been reported that fulfil the Biesecker diagnostic criteria and many more that resemble Proteus syndrome.

Aetiology and Pathogenesis.

Somatic mosaicism, lethal in the non-mosaic state, is the most favoured hypothesis. The sporadic occurrence, 1 : 1 sex ratio, the mosaic distribution of the lesions and variable extent of involvement, never affecting the entire body or an entire organ system, support this hypothesis. It is likely that this is true not only for Proteus syndrome but also for other disorders with vascular malformations and dysregulated growth. Indeed, monozygotic twins discordant for Proteus syndrome were reported by Brockmann et al. [9], and three monozygotic female twins discordant for vascular malformations and dysregulated growth were reported by Oduber et al. [10]. Schwartz and colleagues [11] demonstrated single band differences in monozygotic twins discordant for Proteus syndrome using DNA fingerprinting. Differences in normal and affected areas of another patient with Proteus syndrome were also observed.

The genetic defect of Proteus syndrome has not been identified. It has been hypothesized that entities that combine vascular malformations and dysregulated growth have a polygenic cause and are inherited in a paradominant fashion [12]. One or more mutated genes involved in angiogenesis, combined with one or more mutated genes involved in growth can give rise to such entities. A marked variability in symptomatology within the group of patients with vascular malformations and dysregulated growth should then be expected, as many genes are involved in both angiogenesis and growth, and many combinations of mutated genes are possible.

PTEN mutations have been found in some patients resembling Proteus syndrome but not fulfilling Biesecker’s diagnostic criteria [13,14], but no PTEN mutations were found in Proteus syndrome patients fulfilling the criteria [15,16]. PTEN is a tumour suppressor gene and is involved in the control of apoptosis. Germline mutation in PTEN is associated with Cowden syndrome and Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome, which also represent hamartomatous syndromes.

Say and Carpenter [17] reported a child resembling Proteus syndrome who was mosaic for a duplication of 1q11-q25. A presumed father-to-son [18] and a mother-to-son transmission [19] have been reported. An autosomal dominant inheritance with variable expression and with most cases representing new mutations has been suggested. However, the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome in the parents in these two reports was not convincing. Happle [20] suggested that this exceptional familial aggregation could reflect a paradominant inheritance.

Consanguinity is not more common in this group than in the general population, and together with the sporadic occurrence this makes an autosomal recessive form of inheritance unlikely [21].

There has been one report [22] of a patient whose excised tumour revealed clonal chromosome aberration: mos46, XY, add(9)(p13) [5]/46,XY [30].

Overgrowth can result from hyperplasia (increased number of cells), hypertrophy (increased cell size) or an increase in the interstitium. Proteus syndrome is characterized by local hyperplasia. The molecular basis of the abnormal tissue growth control in Proteus syndrome remains unknown. It is possible that a mutation affecting the receptor of a tissue growth factor or a local regulator of a tissue growth factor is responsible for the syndrome. Yilmaz and co-workers [23] performed a genome-wide scan and could not detect loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and chromosome copy number variations (CNV) in Proteus syndrome using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarrays. In cancers LOH and CNV are common findings.

Rudolph and colleagues [24] demonstrated that fibroblasts of the affected tissue in Proteus syndrome produced an unusual pattern of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP), containing large amounts of an IGFBP with high affinity to IGF-II. Nazarro and colleagues [25] observed no abnormalities in the expression of epidermal growth factor receptors in an immunohistochemical study of skin lesions.

Pathology.

Several cutaneous and visceral hamartomas are observed in Proteus syndrome.

The epidermal naevus found in Proteus syndrome is the non-organoid type [1] and consists of hyperorthokeratosis, acanthosis and papillomatosis without adnexal hyperplasia [25].

The connective tissue naevus shows a highly collagenized fibrous connective tissue. It can be easily differentiated from lesions of neurofibromatosis, in which the connective tissue is very delicate [26].

The lipomatous lesions are usually compound tumours, principally composed of mature adipocytes [26]. Lymphatic and vascular tissue are also found in these lesions.

It is important to note that skull hyperostoses are bony overgrowths and not true tumours [21].

Clinical Features.

Proteus syndrome is characterized by asymmetrical overgrowth of almost any part of the body (Fig. 111.1). Biesecker and colleagues [1,2] published recommendations for diagnostic criteria that are summarized in Box 111.1. The wide range of clinical expression and the absence of any molecular marker or diagnostic laboratory test make it difficult to establish highly sensitive and specific criteria [27].

Mosaic distribution, sporadic occurrence and progressive course are mandatory. The connective tissue naevus, when present, is almost pathognomonic. Hyperostosis of the external auditory canal is uncommon, but is also an important diagnostic clue, particularly in mildly affected individuals [1].

Skin

The most prominent cutaneous features are the connective tissue naevus and the epidermal naevus. The connective tissue naevus is frequently found and is one of the most distinctive features of Proteus syndrome. The plantar connective tissue naevus, the ‘moccasin’ lesion, is very suggestive of Proteus syndrome when present (Fig. 111.2). It is a progressive overgrowth of the plantar surface that acquires a cerebriform appearance with time. It is usually symmetrical, with a firm consistency. The latter is different from the soft consistency of plexiform neurofibroma, which may be present at the same location. The connective tissue naevus can also occur on the palms and rarely in other parts of the body.

Fig. 111.2 Cerebriform soft-tissue thickening of the plantar aspect of the foot (same patient as Fig. 111.1).

The epidermal naevus is a frequent finding. It is usually brown or brownish-black, flat, soft and papillomatous, well demarcated, and asymmetrically present.

Café-au-lait macules, naevus sebaceous, hyperpigmented and hypopigmented diffuse areas and linear streaks have also been described in Proteus syndrome. According to the literature, café-au-lait macules are uncommon and usually occur as a single lesion, small in size [28,29]. The authors’ experience is that pigmentary changes are common in Proteus patients and can be multiple and large in size.

Infrequent manifestations are patchy areas of dermal hypoplasia.

Adipose Tissue

Lipomatous lesions are hamartomas that are principally composed of mature adipocytes, often together with fibrous, vascular and lymphatic tissue (Fig. 111.3). Superficial lesions typically affect the thorax, epigastrium and gluteal region and usually appear later in the course of the disorder [26]. They tend to be confined and self-limited in growth. Intra-abdominal, pelvic and thoracic lipomas, however, have a potential for invasive or aggressive behaviour [1,30–32]. Infiltrative lipomas are common in the paraspinal muscles and limbs [1]. Acute abdomen associated with intra-abdominal lipomatosis [33] and spinal infiltration [27,29,31,34] has been reported.

Abdominal lipomas can be associated with increased abdominal girth.

Dysregulation of adipose tissue with increased and decreased subcutaneous fat at different sites in the same patient has been observed. It may indicate that the regulation of growth and differentiation of the adipose tissue may be involved both locally and systemically [26].

Vascular Malformations

Vascular malformations are developmental defects of capillary, venous or lymphatic channels. They are present at birth and grow proportionately with the patient. They are common in Proteus syndrome [35]. Patients with extensive and severe vascular malformation are at risk of pulmonary embolism [36,37]. Occasionally, abdominal vascular malformations can bleed, requiring urgent surgical management [38]. Cardiac malformations are uncommon.

Disproportionate Overgrowth

Disproportionate asymmetric overgrowth involves especially the arms, legs, feet and digits (Fig. 111.4). Some overgrowth and asymmetry can be present at birth but this is limited. Growth tends to decrease or stop in adolescence but exceptions exist. Macrodactyly is a common feature of Proteus syndrome. Nevertheless, any organ may be involved [1]. Splenomegaly [27] and enlargement of the thymus have been reported [1,39].

Elongation of long bones, bony hypertrophy and hyperostoses are among the most common musculoskeletal abnormalities [29]. Bone elongation and hypertrophy accompany an overgrowing limb in 50% of patients [29].

Hyperostoses (bone overgrowths) of the skull and external auditory meatus, and megaspondylodysplasia are typical features of Proteus syndrome.

Musculoskeletal Abnormalities

Musculoskeletal anomalies are common in Proteus syndrome, especially those associated with bony overgrowth, which can lead to deformities and compromise surrounding structures [29]. Ventilatory failure secondary to massive hypertrophy of ribs [40] and vertebral overgrowth, resulting in spinal cord compression [41], have been reported.

Reviewing the literature, the following have been reported: elongation of the neck and trunk due to spinal anomalies as well as progressive scoliosis and kyphosis; hip asymmetry and hip dislocation; coxa valga; genu valga; vertebral and rib abnormalities; bony protuberances; clinodactyly; syndactyly; polydactyly; valga deformity of the hallux and feet, and hyperflexibility [28,29,42]. It should be stressed, however, that the diagnosis Proteus syndrome is possibly not correct in all reports.

Cohen [21] delineated four types of abnormal growth in the craniofacial skeleton: hyperostoses, unilateral condylar hyperplasia, abnormal calvarial remodelling and craniosynostosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree