11 Immediate Reconstruction of the Breast

11.1 Indications and Approaches for Immediate Reconstruction of the Breast

Introduction

The advent of breast-conserving surgery has helped raise patients’ expectations of a good aesthetic outcome after breast reconstruction. It is therefore vital to offer “immediate” help to patients who have to undergo mastectomy due to factors related to tumor biology. Immediate reconstruction can help spare the patient the psychological trauma of breast amputation. It can also help her feel less abandoned in facing disfigurement, by providing hope that her physical appearance may be restored. These aspects are important in assessing the indication for immediate reconstruction.

Indications

Improved aesthetic outcomes after immediate procedures, as well as numerous long-term studies that have not reported any evidence of an adverse effect of reconstruction on the course of the disease, have helped alter attitudes to the appropriate timing of reconstruction.

In the treatment of breast cancer, increasing attention is being given to psychological and aesthetic factors, provided they do not compromise oncological safety. Such factors were ultimately responsible for the development of breast-conserving surgery. Two-thirds of breast cancer patients now benefit from the use of breast-contouring techniques. However, approximately one-third of patients have to undergo (modified radical) mastectomy.

Nowadays, when a mastectomy is indicated, reconstruction should form part of the treatment planning from the start. Although reconstruction is not always necessary after mastectomy, incorporating reconstruction into the treatment planning at an early stage can help avoid psychological and social sequelae.

It is a prerequisite for immediate reconstruction that the patient should have a strong desire for it and that her view of the treatment and her expectations about the results should be realistic.

Immediate reconstruction used to be available only to women with smaller breast tumors and no clinical evidence of lymph-node involvement. With the exception of those with advanced-stage or inflammatory tumors, increasing numbers of patients are now regarded as being suitable candidates. This trend is mainly due to evidence from prospective controlled studies, which have found no differences in the overall survival or local recurrence rates in women undergoing immediate reconstruction in comparison with control groups.

However, the situation now appears to be changing once again, as it has now been shown in several studies that radio-therapy of the chest wall is beneficial not only with regard to freedom from local recurrences, but above all in relation to the overall survival rate in postmastectomy patients with tumors exceeding 3–5 cm in size and/or involvement of more than three axillary lymph nodes.

However, radiotherapy has a considerable influence on the various methods used for immediate reconstruction.

As capsular contracture can be expected after radiotherapy, implant reconstruction must really be regarded as outdated. Even temporary implant placement (to prevent skin shrinkage) is not advisable, in view of the inevitable tissue trauma (to the pectoralis major, etc.) and for economic reasons (costs of surgery, implants, etc.).

Radiotherapy also has adverse effects in patients who have undergone autologous tissue reconstruction. Radiodermatitis, fat necrosis, and diffuse tissue fibrosis can occur. Such events not only ruin the aesthetic results, but also can lead to painful scarring. Due to its muscle mass, the latissimus dorsi flap is considered to be less vulnerable to radiation, although postirradiation sequelae are not uncommon.

The consequences for the patient are disastrous in two respects. Firstly, the good results of primary reconstruction are lost, and secondly, another autologous tissue transfer procedure (involving surgery, a donor-site defect, complications, and anxiety for the patient) is needed for a satisfactory corrective operation.

In the final analysis, the majority of breast surgeons would not recommend immediate reconstruction in patients who require postmastectomy radiotherapy.

Approaches

Skin-Sparing Mastectomy

It should be recalled that to achieve optimal reconstructive results, the type of mastectomy and the selected reconstruction technique go “hand in hand.” Initially, “normal” mastectomies (with an elliptical incision around the nipple–areola complex) were only occasionally combined with simultaneous reconstruction. Over time, however, this had repercussions for the type of skin resection used in mastectomy.

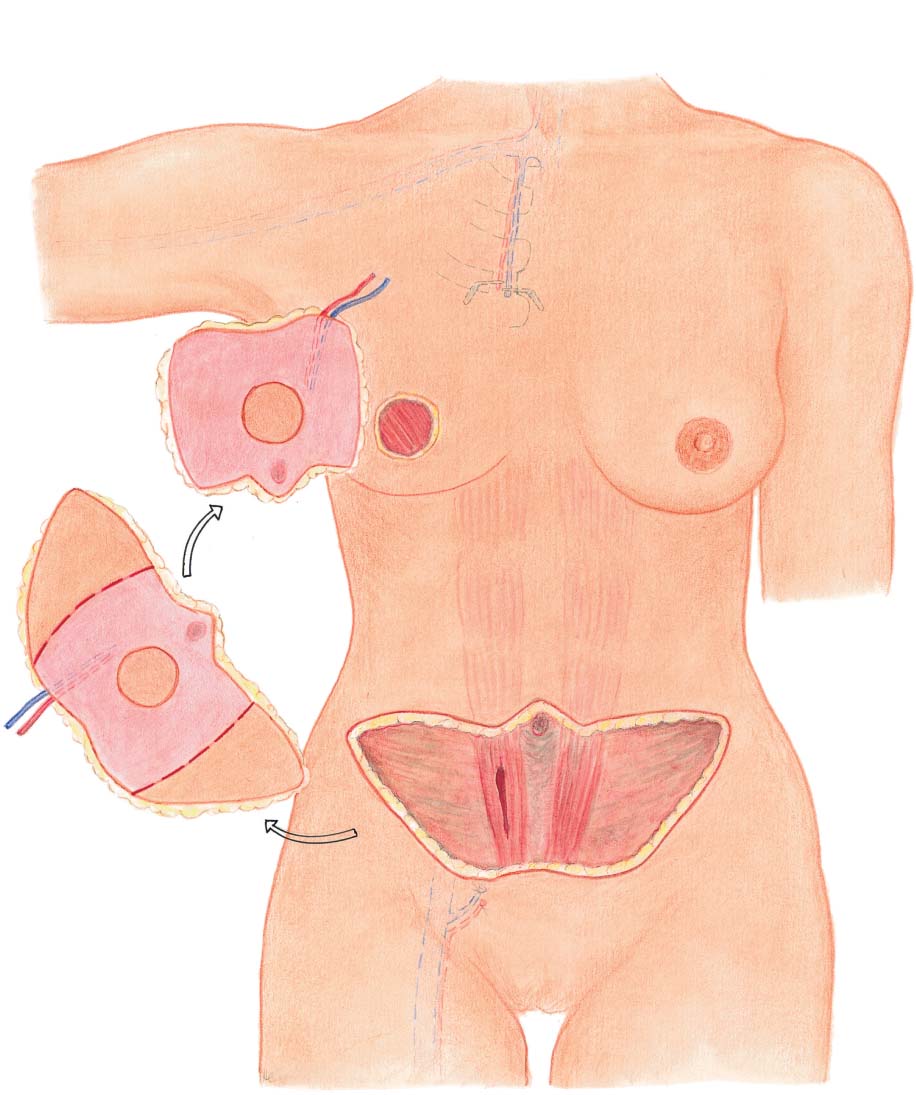

Experience showed that preserving more skin helped optimize the aesthetic results. This is easily understandable when one considers that the breast shape is primarily defined by the skin envelope; also, the position of the inframammary fold has to be preserved or reconstructed. In an ideal situation, where the entire skin envelope is preserved—as in subcutaneous mastectomy—“only” the breast parenchyma that had been lost would have to be replaced in order to obtain a perfect result.

This has contributed to the widespread use of “skin-sparing” techniques in mastectomy with immediate reconstruction, although there is still no standard definition of what technically constitutes a skin-sparing mastectomy.

Variations in skin-sparing techniques range from a small ellipse, to periareolar incisions, to preservation of the entire skin envelope, including the areola ( Fig. 6.59 ) but without the nipple, or including the nipple–areola complex ( Fig.11.2 ).

The wide variety of techniques used makes it difficult to assess comparative studies evaluating the results. Opponents of “skin-sparing” mastectomy fear that oncological safety is being sacrificed in favor of a good aesthetic outcome—which, of course, should never be allowed to happen.

Numerous follow-up studies have shown that preserving the breast skin is not associated with higher rates of local recurrence.

The radicality of the mastectomy procedure depends on the tumor, of course. If there is skin infiltration, it is not possible to preserve the skin. On the other hand, ductal carcinoma in situ can be resected while preserving the entire breast, even sparing the nipple–areola complex, given a 1.0–1.5 cm tumor–nipple distance and adequate excision of the nipple tissue core.

Skin-sparing mastectomies are not for inexperienced surgeons, nor are they routinely indicated. However, these considerations do not preclude the use of this method.

As previously discussed, the mastectomy and reconstruction should ideally be carried out by the same surgeon. It is clearly technically more difficult to perform a mastectomy through an incision around the perimeter of the areola than through a conventional, longer elliptical incision extending over the breast skin. The extra effort is only worth it if it is justified by the reconstructive results.

When oncological and reconstructive surgery are to be performed separately, close communication between the physicians involved is essential.

Skin-Sparing Periareolar Mastectomy

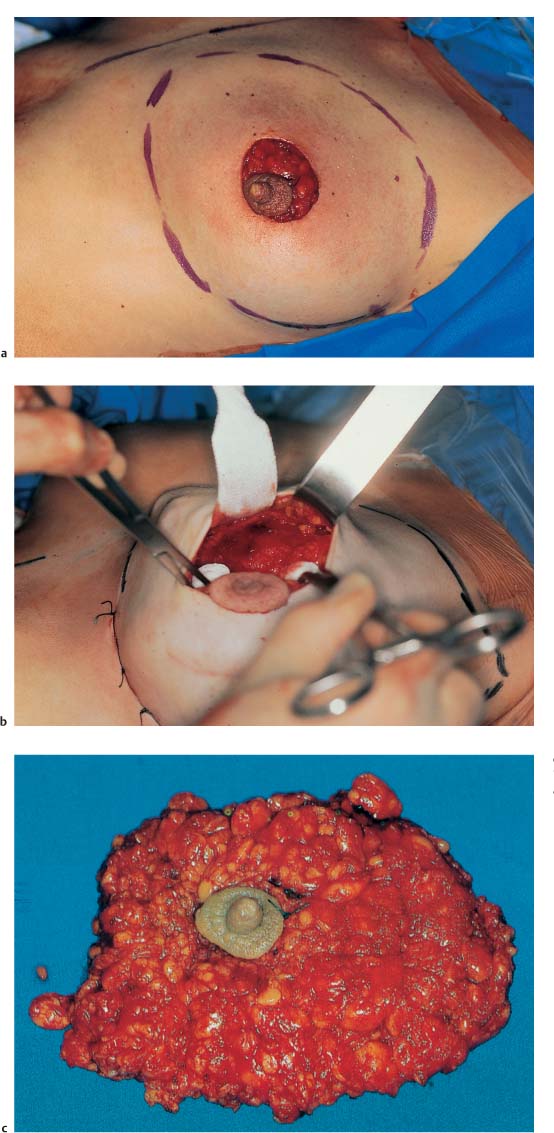

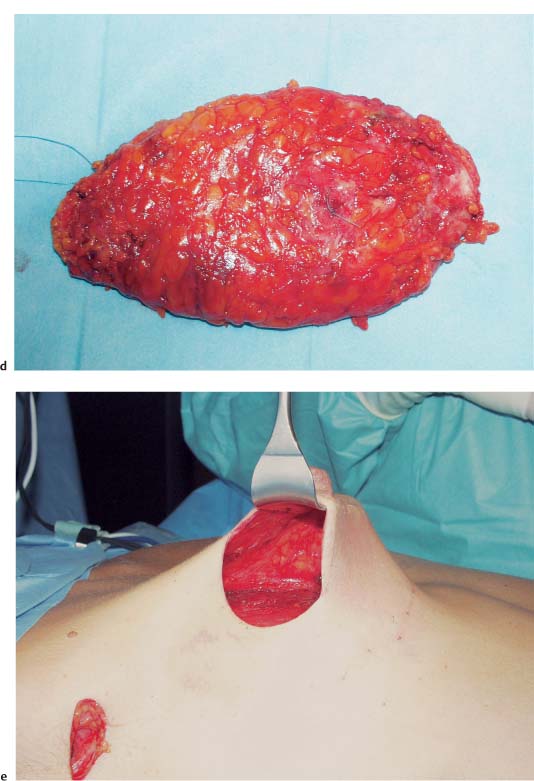

Total mastectomy—like modified radical mastectomy (MRM)—can be performed without oncological compromise through a circular, periareolar incision, with resection of the nipple–areola complex ( Fig.11.3 ). Axillary dissection of level I and II nodes, if necessary, can follow en bloc via the usual axillary approach ( Fig.11.2b ).

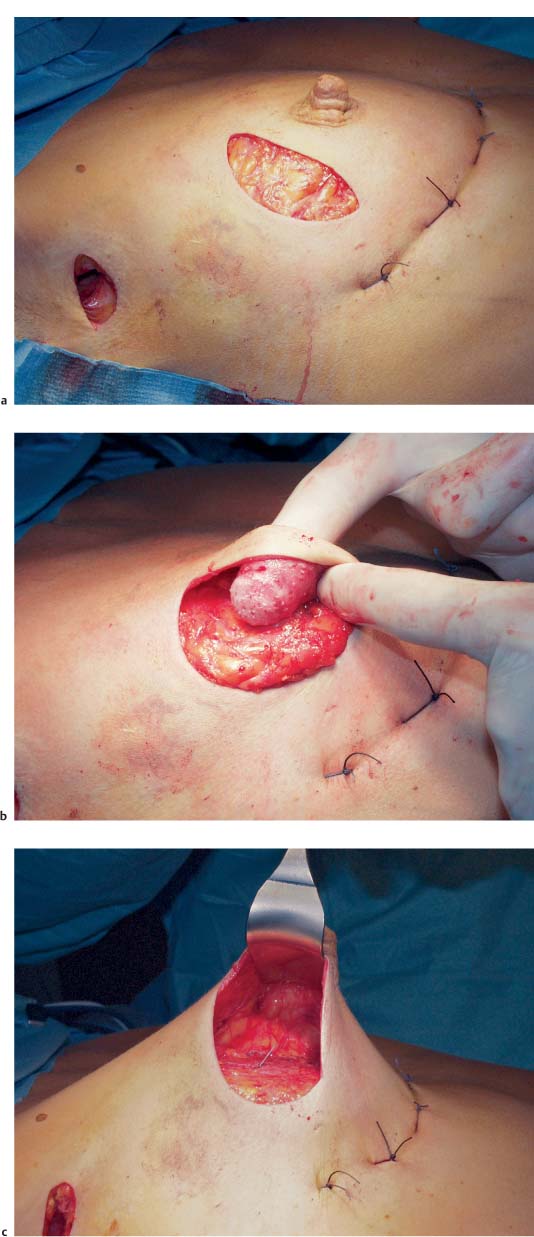

In immediate reconstruction of the breast using a skin or myocutaneous flap, the resected areola is then replaced with a round skin island, from which the nipple–areola complex can later be reconstructed ( Fig.11.10 ).

In implant reconstruction, the round skin defect is closed using a pursestring suture. The resulting scar is later covered with a full-thickness skin graft during reconstruction of the nipple–areola complex ( Fig.11.9 ).

This procedure provides excellent aesthetic results, while ensuring the same high degree of oncological safety as a mastectomy using a conventional incision.

Mastectomy with Nipple Resection and Preservation of the Areola

The “next level” of skin preservation involves conservation of the areola and resection of the nipple. Supporters of this procedure argue that the areola does not contain any glandular tissue and can therefore be maintained just as the skin envelope is preserved. The skin incision is placed around the nipple and then extended transversely through the areola. The incision can then proceed in any direction, preferably inferiorly.

A skin ellipse used as a monitor island can later be used in nipple reconstruction.

The authors do not have any experience with this technique. An example of the procedure is shown in the section on superior gluteal artery perforator (SGAP) flaps ( Fig. 6.59 ).

Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

If certain criteria are met, the entire nipple–areola complex can be retained. Firstly, the tumor has to be at a distance at least 1 cm away from the nipple. In addition, intraoperative frozen-section histopathological diagnosis has to confirm that the breast parenchyma behind the nipple is nonmalignant. In these conditions, oncologically safe resection of ductal cancers is also possible.

Although the surgical technique largely resembles that used for subcutaneous mastectomy, the plane of resection is much more aggressive, corresponding to a total mastectomy in the superficial subcutaneous plane. Also, the nipple is hollowed out. This typically leads to necrosis of the nipple tip (which heals well spontaneously), but it allows the most extensive resection possible of the terminal ducts.

The incision used in this procedure depends on the type of reconstruction. In implant reconstructions, a semicircular areolar incision, possibly extending laterally, is recommended ( Fig.11.8 ).

We do not recommend an inframammary fold approach. Muscular coverage of the implant is poor at this site, and superficial wound healing disorders can quickly spread to the implant. However, muscular coverage near the nipple is very good.

In microsurgical procedures requiring anastomosis with the internal mammary vessels, a generous curvilinear incision placed above or below the nipple is helpful for good exposure of the second or third rib ( Fig.11.15 ).

Impaired circulation of the skin flap or nipple–areola complex can present a problem. This does not have any significant consequences in autologous tissue reconstruction, but it may trigger infection in patients with implants. If this occurs, the areola may need to be removed in a secondary procedure.

Still, excellent reconstructive outcomes are possible with techniques that preserve the entire breast. The patient has to be informed that despite preservation of the nipple, sensation in the nipple–areola complex is lost.

Choice of Reconstructive Procedure

The most difficult decision to be made is choosing the type of breast reconstruction. In principle, any procedure used in secondary reconstruction can also be used for immediate reconstruction. In these cases in particular, the indication needs to be established and adjusted on an individual basis—both in relation to the physical findings and in relation to the oncological situation.

The prerequisites for immediate reconstruction are thus completely different from those in secondary reconstruction. As the procedure is often followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, there is an additional time constraint on the surgical intervention and postoperative course. Weakness resulting from surgery or impaired wound healing has to be taken into consideration and discussed openly with the patient.

With regard to the long-term results of immediate reconstruction, the outcomes of autologous tissue reconstruction are generally superior to those achieved with implant reconstruction. However, special care is needed when using autologous tissue techniques in immediate reconstruction. Major complications are more common than in “simple” implant reconstruction and can delay the start of adjuvant therapy. Transfusion of homologous blood can also potentially worsen the oncological situation.

In addition, the patient has to take the decision for or against any given reconstruction procedure at a time when she is facing the diagnosis of breast cancer and is thus in considerable psychological distress. It is all but impossible for patients to give rational consideration to this “side issue.”

The breast surgeon has to be able to address all of these concerns and has to show sensitivity in striving to reach the right decision in agreement with the patient. The following are some of the key factors that help determine whether a given procedure is appropriate:

The procedure must be desired by the patient herself. She should never be talked into it.

The results of implant reconstruction are reversible, but the results of autologous tissue reconstruction are not.

Autologous tissue reconstruction is much more stressful for the patient.

Implant reconstructions are technically “quick and easy,” but often yield poor aesthetic results. A need for revision surgery may be anticipated.

Invasive tumors often require prompt initiation of chemo-therapy. This tends to rule out complicated microsurgical procedures.

Intraductal tumors are generally cured by mastectomy, and hence there is no time pressure for follow-up treatment. This supports the use of a more complex procedure.

If radiotherapy of the chest wall is anticipated (tumor size exceeding 3–5 cm, involvement of more than three axillary lymph nodes), immediate reconstruction is usually not advisable (see above).

A history of heavy smoking tends to support the use of an autologous tissue procedure, as the perfusion of the mastectomy flaps is usually inadequate.

If the patient has a tendency to prefer autologous tissue reconstruction, but is unable to make a final decision, temporary implant reconstruction may be an option. After primary treatment, the change of procedure can be electively planned and carried out. This is not an “economical” option.

If there is any doubt, immediate reconstruction should not be performed.

The reader is referred to Chapter 6 for further details of the individual procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree