1 Assessment

The primary assessment of the hand injury is like good detective work. It can enable the surgeon to exactly predict which structures may be damaged and need to be identified during the surgery.

1.1 History

History should begin with the occupation and hand dominance of the patient. The mechanism of injury is important and can give clues before surgery is undertaken, for example, knowledge of the type of saw blade can forewarn the surgeon of possible segmental defects in structures. Powered saws tend to result in segmental defects. Relevant past medical history helps to determine the patient’s anesthetic risk.

1.2 Examination

1.2.1 Look

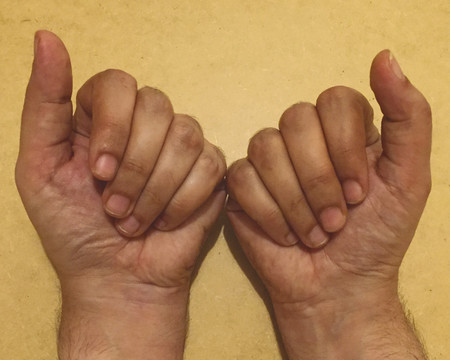

Inspect the cascade of the digits of the hand and identify any obvious irregularity (Fig. 1‑1, Fig. 1‑2, Fig. 1‑3). All fingertips should naturally tend to flex toward the scaphoid tubercle (Fig. 1‑4). Always compare both hands. Assess for wound vascularity by assessing capillary refill at the pulp of the injured digits.

Rotational deformities resulting in scissoring of digits should be documented (Fig. 1‑5, Fig. 1‑6).

In Fig. 1‑2 and Fig. 1‑3, the patient has suffered a knife laceration that has resulted in the division of his or her flexor tendons. Therefore, the normal cascade has been disrupted.

1.2.2 Feel

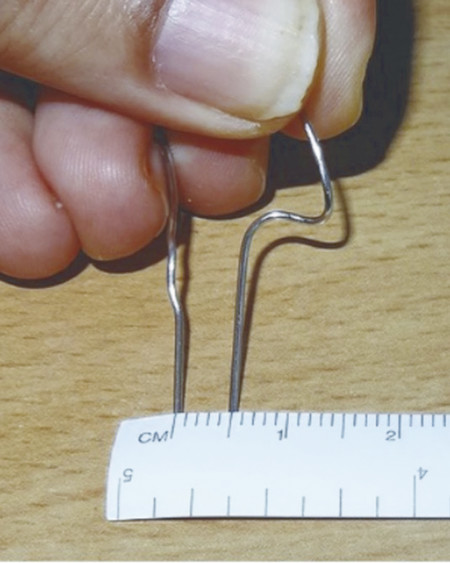

Sensation can be tested with static two-point discrimination (S2PD) (Fig. 1‑7, Fig. 1‑8). Suspect sensory nerve injury if S2PD is greater than 5 mm or the patient has lost the ability to discriminate between one versus two pinpoints. It is important to note that some patients struggle to do this on normal digits and comparison must be made on the uninjured side.

In young children, the tactile adherence test can be used to assess the digital nerve. When gently brushed along a normal digit, a plastic pen will drag due to the normal perspiration. In denervated areas, sweating gets stopped, and this drag is lost; the pen slides with less friction.

Sensory loss in the median, ulnar, and radial nerve distributions should be mapped and documented.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree