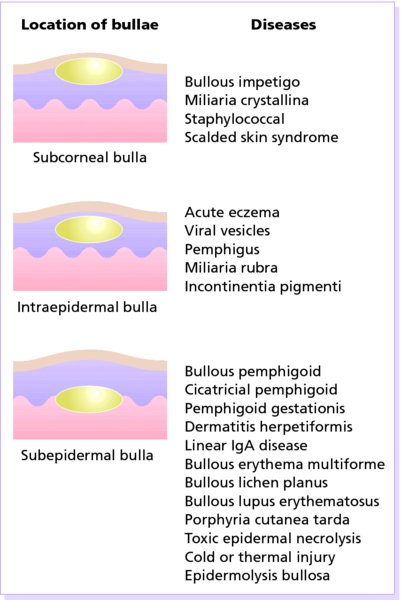

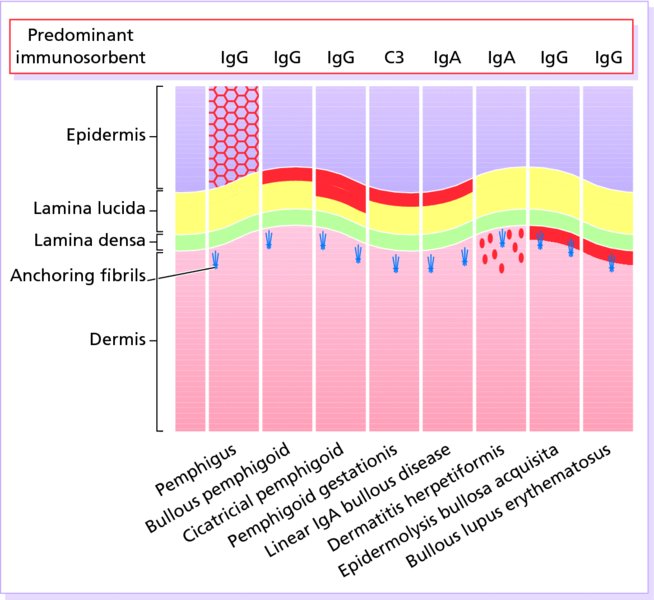

9 Vesicles and bullae are accumulations of fluid within or under the epidermis. They have many causes, and a correct clinical diagnosis must be based on a close study of the physical signs. The appearance of a blister is determined by the level at which it forms. Subepidermal blisters occur between the dermis and the epidermis. Their roofs are relatively thick and so they tend to be tense and intact. They may contain blood. Intraepidermal blisters appear within the prickle cell layer of the epidermis, and so have thin roofs and rupture easily to leave an oozing denuded surface. This tendency is even more marked with subcorneal blisters, which form just beneath the stratum corneum at the outermost edge of the viable epidermis, and therefore have even thinner roofs. Sometimes the morphology or distribution of a bullous eruption gives the diagnosis away, as in herpes simplex or zoster. Sometimes the history helps too, as in cold or thermal injury, or in an acute contact dermatitis. When the cause is not obvious, a biopsy should be taken to show the level in the skin at which the blister has arisen. A list of differential diagnoses, based on the level at which blisters form, is given in Figure 9.1. Figure 9.1 The differential diagnosis of bullous diseases based on the histological location of the blister. The bulk of this chapter is taken up by the three most important immunobullous disorders – pemphigus, pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis (Table 9.1) – and by the group of inherited bullous disorders known as epidermolysis bullosa. Our understanding of both groups has advanced in parallel, as several of the skin components targeted by autoantibodies in the acquired immunobullous disorders are the same as those inherited in an abnormal form in epidermolysis bullosa. Table 9.1 Distinguishing features of the three main immunobullous diseases. Many chronic bullous diseases are caused directly or indirectly by antibodies binding to normal tissue antigens. In the pemphigus family, these are cadherins holding keratinocytes of the epidermis together. In the pemphigoid family, antigens are constituents of the dermo-epidermal junction that anchor the epidermis to the dermis. In dermatitis herpetiformis, the antigen is a transglutaminase. Pemphigus is often severe and potentially life-threatening. There are two main types. The most com- mon is pemphigus vulgaris, which accounts for at least three-quarters of all cases, and for most of the deaths. Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. The other important type of pemphigus, superficial pemphigus, also has two variants: the generalized foliaceus type and localized erythematosus type. A few drugs, led by penicillamine and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), can trigger a pemphigus-like reaction, but autoantibodies are then seldom found. Finally, a rare type of pemphigus with severe mucosal erosions, paraneoplastic pemphigus, is associated with neoplasms such as thymoma, Castleman’s tumour and lymphoma. All types of pemphigus are autoimmune diseases in which pathogenic immumoglobulin G (IgG, predominantly IgG4) antibodies bind to antigens within the epidermis. The main target antigens are desmoglein 3 (in pemphigus vulgaris) and desmoglein 1 (in superficial pemphigus). Both are cell-adhesion molecules of the cadherin family (see Table 2.5), found in desmosomes. The antigen–antibody reaction interferes with adhesion, causing the keratinocytes to fall apart (acantholysis). Pemphigus vulgaris is particularly common in Ashkenazi Jews and people of Mediterranean or Indian origin. There is linkage between the disease and certain human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles. An endemic, superficial form of pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) is prevalent in certain areas of South America and Tunisia. It is postulated that a combination of genetic susceptibility (also linked to HLA class II alleles) and environmental exposure to a putative insect vector results in the disease. Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by flaccid blisters of the skin (Figure 9.2) and mouth (Figure 9.3). The blisters rupture easily to leave widespread painful erosions. Most patients develop the mouth lesions first. Shearing stresses on normal skin can cause new erosions to form (a positive Nikolsky sign). In the vegetans variant (Figure 9.4), heaped up cauliflower-like weeping areas are present in the groin and body folds. The blisters in pemphigus foliaceus are so superficial, and rupture so easily, that the clinical picture is dominated more by weeping and crusted erosions than by blisters. In the rarer pemphigus erythematosus the rash may have a predilection for photo-exposed areas; on the face, lesions are often pink, rough and scaly. Figure 9.2 Pemphigus vulgaris: widespread erosions that have followed blisters. Figure 9.3 Painful sloughy mouth ulcers in pemphigus vulgaris. Figure 9.4 Pemphigus vegetans in the axilla, some intact blisters can be seen. The course of all forms of pemphigus is prolonged, even with treatment, and the mortality rate of pemphigus vulgaris is still at least 15%. Most patients have a terrible time with weight gain and other side effects from systemic corticosteroids and from the lesions, which resist healing. However, about one-third of patients with pemphigus vulgaris will go into complete remission within 3 years. Superficial pemphigus is less severe. With modern treatments, most patients with pemphigus can live relatively normal lives, with occasional exacerbations. Complications are inevitable with the high doses of steroids and immunosuppressive drugs that are needed to control the condition. Indeed, side effects of treatment are now the leading cause of death. Infections of all types are common. The large areas of denudation may become infected and smelly, and severe oral ulcers make eating painful. Widespread erosions may suggest a pyoderma, impetigo, epidermolysis bullosa or ecthyma. Mouth ulcers can be mistaken for aphthae, Behçet’s disease or herpes simplex infection. Scalp erosions suggest bacterial or fungal infections. Pemphigus erythematosus is now considered as an overlap syndrome with lupus erythematosus. Biopsy shows that the vesicles are intraepidermal, with rounded keratinocytes floating freely within the blister cavity (acantholysis). Direct immunofluorescence (p. 42) of adjacent normal skin shows intercellular epidermal deposits of IgG and C3 (Figure 9.5). The serum from a patient with pemphigus contains antibodies that bind to the desmogleins in the desmosomes of normal epidermis, so that indirect immunofluorescence (p. 42) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays can also be used to confirm the diagnosis. The titre of these antibodies correlates loosely with clinical activity and may guide changes in the dosage of systemic steroids. Figure 9.5 Immunofluorescence (red) in bullous diseases. Because of the dangers of pemphigus vulgaris, and the difficulty in controlling it, patients should be treated by dermatologists. Resistant and severe cases need very high doses of systemic steroids, such as prednisolone (Formulary 2, p. 420) 60–180 mg/day. These ‘industrial doses’ work because prednisolone upregulates the expression of desmoglein molecules on the surfaces of keratinocytes, in addition to other effects above and beyond their anti- inflammatory ones. The dose is reduced only when new blisters stop appearing. Immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and mycophenylate mofetil, are often used as steroid-sparing agents. As ever, the benefit of increasing immunosuppression has to be weighed up against the risk of treatment-associated adverse reactions. With long-term corticosteroid therapy being the norm it is worth commencing bone and gastric protection at the earliest opportunity. New and promising approaches include plasmapheresis, immunoadsorption and administration of intravenous immunoglobulin. Rituximab is a humanized murine monoclonal antibody to CD20 that may knock out B cells, pre-B cells and antibody production. Dapsone may sometimes be helpful, especially to allow healing. After control has been achieved, prolonged maintenance therapy and regular follow-up will be needed. In superficial pemphigus, smaller doses of systemic corticosteroids are usually needed, and the use of topical corticosteroids may help too. Hailey–Hailey disease (familial benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomal dominant blistering condition resulting from mutations in the ATP2C1 gene located on chromosome 3. The gene encodes a calcium–manganese pump essential for desmosomal adhesion. Mutations result in suprabasal keratinocyte acantholysis. Clinically, this manifests as flaccid vesicopustules and superficial erosions coalescing to form larger scaly circinate plaques. These have a predilection for sites of skin friction, typically the neck, submammary and intertriginous areas. Secondary infection, both fungal and bacterial, is common. There is no universally effective treatment. Mild cases can usually be managed with topical corticosteroids, antibiotics, antifungals or vitamin D analogues. More severe cases may require systemic therapy with ciclosporin, methotrexate, dapsone or retinoids. There are case reports of successful outcomes with various surgical and ablative laser procedures. This is a common cause of blistering in children. The bullae erupt suddenly, are flaccid, often contain pus and are frequently grouped or located in body folds. Bullous impetigo is caused by Staphylococcus aureus. A toxin (exfoliatin) elaborated by some strains of S. aureus makes the skin painful and red; later it peels like a scald. The staphylococcus is usually hidden (e.g. conjunctiva, throat, wound, furuncle). The toxin causes dyshesion of desmoglein I, the same cadherin injured in pemphigus foliaceus. Here sweat accumulates under the stratum corneum leading to the development of multitudes of uniformly spaced vesicles without underlying redness. Often this occurs after a fever or heavy exertion. The vesicles look like droplets of water lying on the surface, but the skin is dry to the touch. The disorder is self-limiting and needs no treatment. As its name implies, the lesions are small groups of pustules rather than vesicles. However, the pustules pout out of the skin in a way that suggests they were once vesicles (like the vesico-pustules of chickenpox). Oral dapsone (Formulary 2, p. 413) usually suppresses it. Many patients have IgA antibodies to intercellular epithelial antigens. Severe acute eczema, especially of the contact allergic type, can be bullous. Plants such as poison ivy, poison oak or primula are common causes. The varied size of the vesicles, their close grouping, their asymmetry, their odd configurations (e.g. linear, square, rectilinear), their intense itch and a history of contact with plants are helpful guides to the diagnosis. In pompholyx, highly itchy small eczematous vesicles occur along the sides of the fingers, and sometimes also on the palms and soles. Some call it dyshidrotic eczema, but the vesicles are not related to sweating or sweat ducts. The disorder is very common, but its cause is not known. Some viruses create blisters in the skin by destroying epithelial cells. The vesicles of herpes simplex and zoster are the most common examples. These can be hard to separate on clinical grounds and only the two most important, pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis, are described in detail here. Several others are mentioned briefly. Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune disease. Serum from about 70% of patients contains antibodies that bind in vitro to normal skin at the basement membrane zone. However, their titre does not correlate with clinical disease activity. The IgG antibodies bind to two main antigens: most commonly to BP230 (which anchors keratin intermediate filaments to the hemidesmosome, p. 14), and less often to BP180 (a transmembrane molecule with one end within the hemidesmosome and the other bound to the lamina lucida). Complement is then activated (p. 24), starting an inflammatory cascade. Eosinophils often participate in the process causing the epidermis to separate from the dermis. Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic, usually itchy, blistering disease, mainly affecting the elderly (mean age of onset around 80 years). Usually, no precipitating factors can be found, but rarely drugs, ultraviolet radiation exposure or radiotherapy seem to play a part. Several neurological diseases may pre-date the onset of the disease; including cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis, and these are now considered risk factors for bullous pemphigoid. The skin often erupts with smooth itching red plaques in which tense vesicles and bullae form (Figure 9.6). Occasionally they arise from normal skin. The flexures are often affected; the mucous membranes usually are not. The Nikolsky test is negative. Denudation occurs only over small areas as blisters rupture, so the disorder would not be fatal were it not for its propensity to affect elderly people who may be already in poor health; factors carrying a high risk include old age, the need for high steroid dosage, and low serum albumin levels.

Bullous Diseases

Age

Site of blisters

General health

Blisters in mouth

Nature of blisters

Circulating antibodies

Fixed antibodies

Treatment

Pemphigus

Middle age

Trunk flexures and scalp

Poor

Common

Superficial and flaccid

IgG to intercellular adhesion proteins

IgG in intercellular space

Steroids Immunosuppressives

Pemphigoid

Old

Often flexural

Good

Rare

Tense and blood-filled

IgG to basement membrane region

IgG at basement membrane

Steroids Immunosuppressives

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Primarily adults

Elbows, knees, upper back, buttocks

Itchy

Rare

Small, excoriated and grouped

IgG to the endomysium of muscle

IgA granular deposits in papillary dermis

Gluten-free diet Dapsone Sulphapyridine

Bullous disorders of immunological origin

The Pemphigus family

Cause

Presentation

Course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Hailey–Hailey disease

Other causes of subcorneal and intraepidermal blistering

Bullous impetigo (p. 215)

Scalded skin syndrome (p. 217)

Miliaria crystallina (p. 169)

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis

Acute dermatitis (see Chapter 7)

Pompholyx (p. 94)

Viral infections (see Chapter 16)

Subepidermal immunobullous disorders

The Pemphigoid family

Presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree