FIGURE 13–1 Wet-to-dry dressings Wet-to-dry dressings adhere to healthy granulation tissue and can cause capillary destruction upon removal. In addition to causing the wound to bleed, removal of dry adhered dressings can be very painful for the patient.

The concept of using a wet-to-moist dressing to avoid this trauma may still cause injury. The dressing is prepared in the same manner as a wet-to-dry dressing except the gauze is applied with more moisture with the intent that it will remain moist until removal. Nevertheless, it may become a wet-to-dry dressing in practice. A study of the mechanism of action of saline dressings suggests that they function as an osmotic dressing.6 Normal saline is isotonic. As water evaporates from the saline dressing, it becomes hypertonic and fluid from the wound tissues is drawn into the dressing in an attempt to reestablish isotonicity. However, wound fluid is not merely water; it contains blood and proteins that may begin to form an impermeable layer on the dressing’s surface. At this point, fluid from the wound is unable to replace the fluid lost from the dressing by evaporation and the dressing dries out completely. Consequently, unless the dressing is changed frequently, or remoistened between dressing changes, it will still function as a wet to dry.

Additionally, cooling of the tissues at dressing changes may impede healing. Evaporation of water from a surface results in a reduction of temperature at that surface. Reduction in tissue temperature has multiple physiologic effects, including local reflex vasoconstriction and hypoxia, impairment of leukocyte mobility and phagocytic efficiency, and increased affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen—all of which not only impede healing but increase susceptibility to infection.6

Gauze dressings present no physical barrier to the entry of exogenous bacteria. An in vitro study showed that bacteria were capable of penetrating up to 64 layers of dry gauze, and moistened gauze provides even less of a barrier to bacterial penetration, again increasing the risk of infection. In a literature review of 3047 wounds, the overall infection rate for wounds dressed with moisture-retentive dressings was 2.6%, whereas the infection rate for gauze-dressed wounds was 7.1%.6

Wet-to-dry dressings may incur more labor for the clinician or caregiver and more costs for the health care system. In order for gauze to remain continuously moist to support optimal healing, it must be either changed frequently or remoistened with additional saline. This requires additional labor on the part of the clinician or the lay caregiver. Dressing changes two or three times a day used to be common. In today’s reimbursement climate, this practice is no longer feasible, not only from a reimbursement perspective, but also from the standpoint of best patient outcomes. In home health care, multiple dressing changes a day require the expense of extra travel, home visits, and post-visit time for documentation. Even without the expense of travel in acute or long-term care settings, frequent dressing changes still require time that could be used for other patient care tasks.

GOAL-BASED WOUND MANAGEMENT7

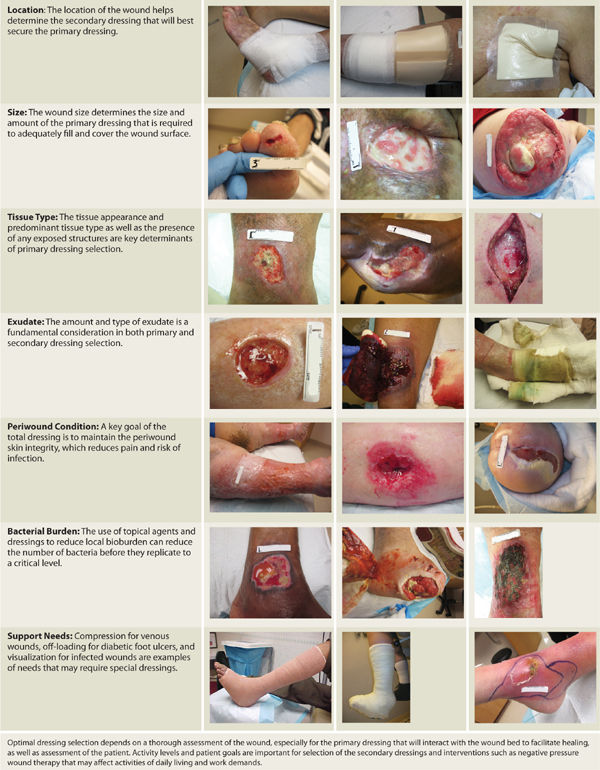

Assessment of the patient with an open wound involves a holistic approach and there are many facets of the evaluation that go beyond purely the physical makeup of the wound, for example, the appropriate diagnosis of the wound etiology, patient comorbidities, nutrition, and tissue oxygenation. Open wounds are dynamic and are continuously changing; therefore, dressing selection for optimal healing must also change. It is rare that a singular treatment plan for any given wound will remain the same throughout the healing process. Decision making relative to treatment is based on a thorough assessment of the patient and the wound at regular intervals so that timely changes in the care plan can be made. Specific wound and patient characteristics to be assessed that will drive treatment decisions are illustrated in TABLE 13-1.

TABLE 13-1 Assessment of the Wound and the Patient for Dressing Selection

Location

The location of the wound on the patient has less to do with the primary dressing (the dressing that is in contact with the wound bed) and more to do with how the dressing may be secured. Wounds located on the torso will require a dressing that is self-adhering, has an incorporated adhesive border, or is secured with additional tape. Wounds on the extremities can be secured with self-adhering dressings, gauze rolls, tubular bandages, or stretch net. The skin condition, patient activity level, potential trauma, possible contamination, and the desire to bathe or shower are also factors to be considered when selecting the secondary dressing.

Size

The size of the wound determines the size of the dressing required to adequately fill and cover the wound surface. Undermining or sinus tracts need to be loosely packed or filled, usually with the same primary dressing. All categories of dressings are available in a variety of sizes and shapes to accommodate the dimensions of most wounds. The outlier in the size consideration is the very large wound requiring frequent dressing changes (eg, a large surgical wound) in which case negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) may accomplish more rapid reduction in wound size and allow more patient activity. (See Chapter 15, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy.) If wound healing is not the immediate or long-term goal, a better dressing selection is one that is cost-effective; requires less frequent changes; and manages exudate, odor and pain.

Tissue Type

The predominant tissue type and the exposure of vital structures such as bone, tendon, and muscle are key determinants of dressing selection. Healthy granulating wound beds and exposed viable structures need to be kept moist and protected from trauma. The presence of necrotic tissue requires a decision about appropriateness and type of debridement.

Exudate

The amount and type of exudate is a fundamental consideration in dressing selection. The optimal dressing material adequately manages wound drainage by wicking the exudate into a secondary dressing. This prevents pooling of exudate on the wound surface, which can become a nidus for bacterial growth as well as a source of leakage and maceration of the surrounding skin. A dry tissue bed requires hydration, a moist bed needs to be maintained, and a wet surface with large amount of exudate requires absorption. The exudate levels will also determine frequency of the dressing change.

Periwound Condition

A key goal of any dressing is to maintain the periwound skin and prevent maceration (ie, over-wetting), stripping/mechanical trauma, prevention and treatment of rashes, and prevention of tape irritation. A dressing that adequately manages exudate is the primary strategy for maintaining intact skin. The use of a barrier wipe or ointment also protects the skin from moisture as well as from trauma during tape removal. Silicone-backed dressings help prevent pain and trauma at dressing change and facilitate remodeling of the wound areas that have reepithelialized. A rash or blistering of the periwound area may be an indication of an allergic reaction to a particular dressing or tape; the location and distribution of the rash or blisters are a clue to the etiology. A true allergic reaction usually results in the presence of rash or blistering where the tape or irritating agent was in contact with the skin.

Blistering, especially on one side of dressing edge, is usually indicative of tape being applied with tension, thus resulting in a separation of the epidermis and dermis that subsequently fills with fluid, hence the blister.8 Applying tape without tension by anchoring in the middle and smoothing outward can prevent this.

Bacterial Burden

All wounds are contaminated. As bacterial levels rise, the potential for infection in the deeper tissue increases. Even in the absence of gross infection, wound healing can be affected by the increase of proteases, toxins, and other consequences of bacteria. The use of topical agents and dressings to reduce local bioburden can reduce the number of bacteria before they rise to a critical level and negatively influence wound healing. Multiple dressing options exist to address bacteria while still meeting the environmental needs of the wound. (See the section Antimicrobial Dressings at the end of this chapter.)

Pain

Every patient has an acceptable level of pain, and every treatment plan includes strategies to mitigate or eliminate pain to the extent possible, or at least to the patient’s acceptable level. A survey conducted in 2002 in 11 European and North American countries identified the top issues in wound healing as (1) preventing trauma to the wound surface and periwound skin and (2) preventing pain to the patient during dressing changes.9 Maintaining a moist wound bed, selecting a nonadherent dressing that is easy to remove, gentle cleansing, administering oral and IV pain medications at the optimal times, and using a topical anesthetic for procedures such as debridement are strategies that reduce the pain associated with both acute and chronic wound care. In some cases, having the patient don gloves and assist in the dressing removal can help minimize pain and reduce anxiety.

Support Needs

Topical care is only a part of the multifaceted approach to achieving wound healing. A thorough patient assessment to determine wound etiology and the appropriate supportive management is an integral part of the treatment plan. To that end, dressing choices are also determined by the supportive care or other medical interventions required to manage the underlying etiology and comorbidities. Examples include but are not limited to

Patients with venous disease requiring compression wraps or patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) off-loaded with total contact casts require dressings that may be left in place until the compression or casts are removed.

Patients with venous disease requiring compression wraps or patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) off-loaded with total contact casts require dressings that may be left in place until the compression or casts are removed.

Patients with suspected or confirmed infection may require frequent observation of the wounds.

Patients with suspected or confirmed infection may require frequent observation of the wounds.

Patients with periwound dermatitis being treated with topical steroids require dressings changed at the frequency needed for the reapplication of medications.

Patients with periwound dermatitis being treated with topical steroids require dressings changed at the frequency needed for the reapplication of medications.

Quality of Life

Optimal wound management involves a holistic approach that considers patient wishes and lifestyle, work requirements, and activities of daily living. An important first consideration is the overall goal for the wound, for example, can it be healed? In the case of a patient with a terminal illness or a wound of the lower extremity with inadequate circulation, the goal may not be healing but pain and odor control, prevention of infection, and prevention of wound deterioration. The patient who desires or requires showering needs a waterproof dressing if showering with the wound exposed is not appropriate. The working patient needs a treatment plan that accommodates the working schedule and environment, as well as a dressing that can be camouflaged, hidden, or at least be presentable. In summary, the patient needs a dressing that will prevent the wound from interrupting daily life as much as possible.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE IDEAL WOUND DRESSING10–16

There is no “one size fits all” for dressing selection for open wounds. There are literally thousands of dressings available considering the various categories, shapes, and sizes. Although the form (ie, the ingredients) of the dressing is important, the function, or how it will optimize the wound environment, is more essential in decision making. That being said, there is almost always more than one option available to meet the assessed needs of any wound. TABLE 13-2 describes the desired characteristics of an ideal wound dressing.

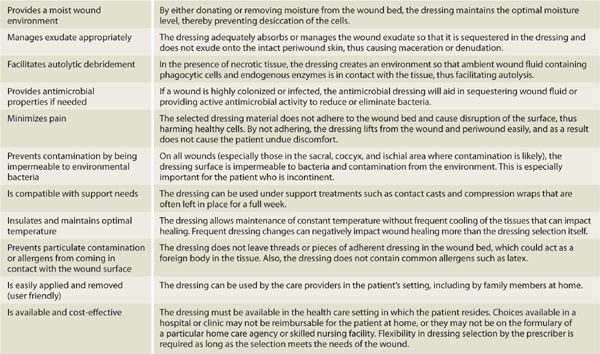

TABLE 13-2 Characteristics of the Ideal Wound Dressing