It has been estimated that the prevalence of chronic, nonhealing wounds (NHWs) is about 2% of the US population. As a point of reference for this number, this estimate of prevalence is very similar to that of heart failure in America. The overall cost burden of NHWs is estimated conservatively at $35 to $50 billion per year. The impact on the health care system can be great, as those with NHWs have an average of at least two comorbid factors, often including diabetes, heart disease, or obesity. In addition, the presence of NHWs takes an emotional toll (including quality of life) on the patient, as well as their family, significant others, and community. NHWs can be life-impairing or life-altering for a short period or can continue for many years. They affect the very young to the very old, and have become a rapidly expanding health issue for our American veterans.

Wounds is a broad term that can encompass a variety of “types” of wounds. On the basis of the wound type, a “wound” may also be referred to as an “ulcer.” These terms are used interchangeably, and it is acceptable to do so. There are countless etiologies for wounds, but there are broad and common wound categories, which include (but are not limited to) pressure ulcers (PrUs), thermal injuries (frostbite and burns), venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, traumatic wounds, surgical wounds, infectious wounds (such as from abscesses), skin tears, wounds from systemic and chronic disease, and more. It is imperative that all types of health care providers, regardless of the setting, possess a basic working knowledge of wounds. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a high-level overview of wounds, with specific information that is applicable for the primary care clinicians.

Patients with NHWs are present in every health care setting. Clinicians may find themselves both intimidated and uninformed about just what to do about these health issues. Providers understand that wounds are complex, but often do not understand wound complexities. Unquestionably, the best action to take in providing quality patient care is to acquire the human, material, and equipment resources available for wounded patients in the particular geographical location. Certified wound ostomy continence nurses (CWOCNs) are the gold standard in nursing resources.

WOUND HEALING

A brief review of the phases of wound healing, physiology, and repair is essential to understand the treatment of any wound. Clinicians must address both the etiology and complications of a wound that has not healed. The “normal” timeline of wound healing is considered to be orderly. Wounds that do not progress should be assessed and determined whether they are acute or chronic. Ascertaining a thorough history of the wound is imperative to determining the course of care and cannot be overemphasized (Box 22-1).

Arguably, the most important question in the history surrounds the age of the wound, which automatically determines chronicity. An acute wound is considered to be one that passes through the wound healing process and responds to the local treatment within the expected time frame. Acute wounds such as surgical wounds, skin tears, and lacerations respond generally to standard treatment, though any wound can become chronic.

Gathering Wound History |

How did the wound occur?

When did the wound occur?

When was the wound noticed? This question is important for neuropathic patients.

What treatment was initially given to the wound?

What other wound treatments have been given and when?

Have any home or alternative remedies been used, and if so what?

Has the wound been infected?

Has any medication been prescribed or used on the wound?

Was it prescribed for this wound or left over from another occurrence?

Is there pain, including location, characteristics, occurrence, relievers, triggers?

Does this wound open and close cyclically?

Conversely, a wound that does not respond to treatment within 30 days is considered to be a chronic wound. Assumed to be stuck in the inflammatory process, a chronic wound has itself become a chronic response with cellular transaction changes. Because the logical order of healing demands the inflammatory phase give way to proliferation, if the inflammatory phase is in control of the wound environment, healing will not progress. Chronicity can occur with any type of wound, but is most often found in PrUs, leg ulcers, and neuropathic ulcers.

Phases of Wound Healing

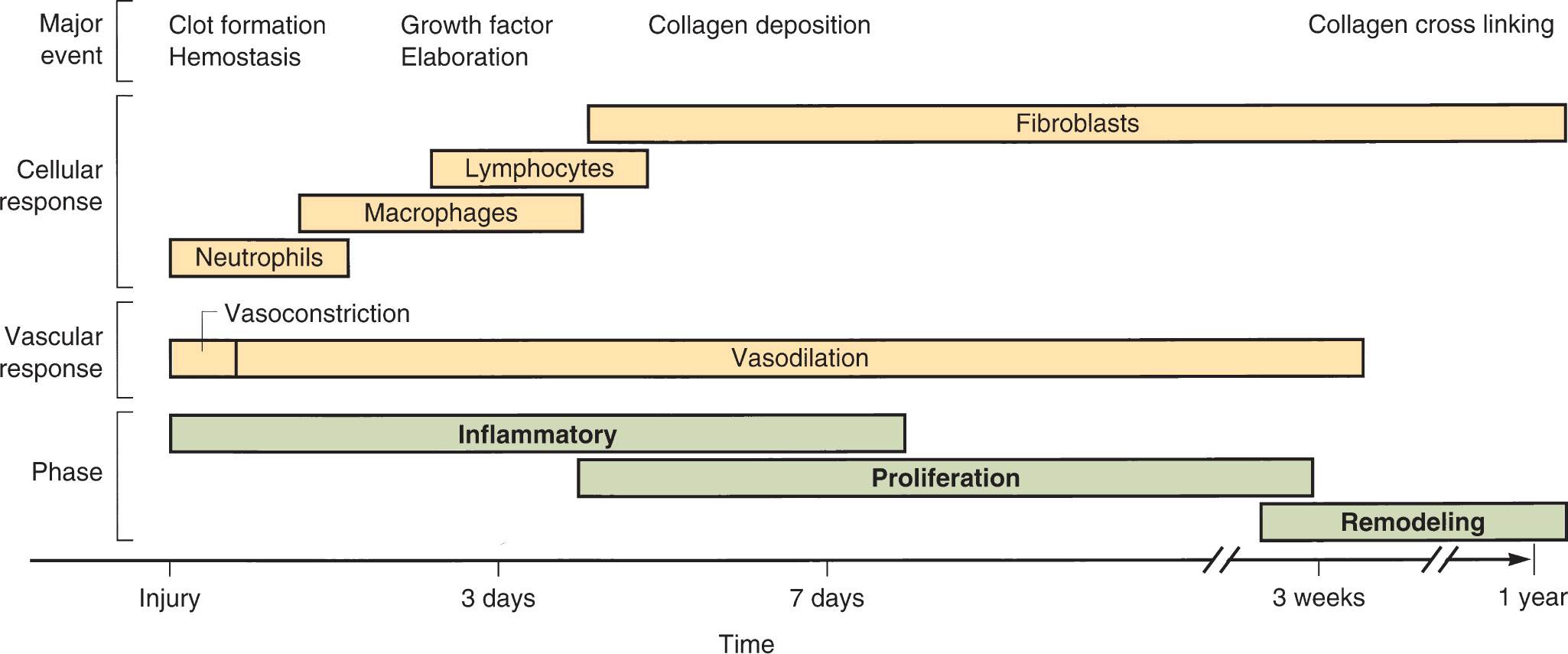

As mentioned, wound healing should progress through an orderly process (Figure 22-1). At the time of wounding, there is a disruption of cells, collagen, and tissues, which causes a hemorrhage. This event activates a series of cellular transactions that stop the hemorrhage, and ultimately form a fibrin clot, within minutes of the injury. Within 10 to 15 minutes, this clot is dissolved to allow the next cascade of events to occur, and it is at this point that the inflammatory stage begins.

Inflammatory phase

Initially in the inflammatory phase, the cellular trash is contained and removed as neutrophils and macrophages arrive. There is also a vasodilation process that occurs, which permits plasma and blood cells to pass into the wound bed, bringing growth factors and a host of other cells to the wound. Clinical signs of the inflammatory phase include edema, erythema, and exudate. By days 3 to 5, the inflammatory phase will lead to the proliferative phase.

FIG. 22-1. Timeline of phases of wound healing with dominant cell types and major physiologic events.

Proliferative phase

The proliferative phase is the time when the wound surface is restored and connective tissue is deposited. Beefy-red granulation tissue is formed, giving way to wound contraction and epithelial migration. It is in this stage that the growth factors that were released show their results, and new cells are formed to heal the wound, and provide collagen deposition and other transactions to result in tissue healing.

Remodeling phase

The remodeling phase (also called maturation) may begin as early as 1 week postinjury. Proliferation results in collagen deposition, but this deposition is unorganized. The maturation phase consists of collagen and cellular remodeling. This remodeling results in strength of the skin. At the end of proliferation, the skin has about 20% tensile strength, while at the completion of remodeling, the tensile strength approaches 80%.

Complications

Regardless of etiology, wounds are intended to pass through the phases of wound healing without any complication. However, comorbid conditions, chronicity, and confounding factors can impair the velocity and the mechanisms with which repair should occur. Any wound that is older than 1 year deserves a biopsy (including the margin of the wound) to rule out malignancy and transformation of cells that can signal other conditions.

Other variables prompting a workup include a cyclic wound, as the cycle itself is a symptom of some type of impairment in the wound environment at the very least. Cyclical wounds are chronic wounds that open and close; that is, wound closure cannot be sustained. This is the characteristic wound that heals, and reopens in a few days, or almost closes and then opens exponentially. This wound cycle of nonhealing can be due to circulatory conditions and autoimmune conditions that are not detected or controlled, and if the wound is associated with a bone, often signal acute or chronic osteomyelitis.

Infection of wounds, which can often be very subtle, can also lead to chronicity. Certainly, cellulitis, sepsis, and classic signs like purulent exudate and foul odor are indicators that are more evident. Often, the only sign of wound infection is delay of healing. Exploration and workup of these contributors to chronicity will be discussed later in this chapter.

Understanding the causes of wounds assists with differential diagnosis, leading to appropriate referral and management. Generally, wound healing principles are consistent across wound types. However, because wounds heal when the etiology is also treated, becoming familiar with etiologies is important. The following are common wounds seen in primary care but are certainly not inclusive of all wound types.

PRESSURE ULCERS

PrUs affect about 3 million people per year across all care settings, including at home, and almost $12 billion is spent on PrU treatment in the United States alone. The number of people affected and associated costs are only projected to increase in the coming years. Infection is the most common complication of PrUs. Geriatric patients with PrUs develop bacteremia at the rate of 3.5 per 10,000 hospital discharges, with a mortality rate approaching 50%. Statistics related to morbidity and mortality in relation to human skin wounds have not generally been collected, but the implications of poor life outcomes related to wounds are anecdotally noted (Sen et al., 2009).

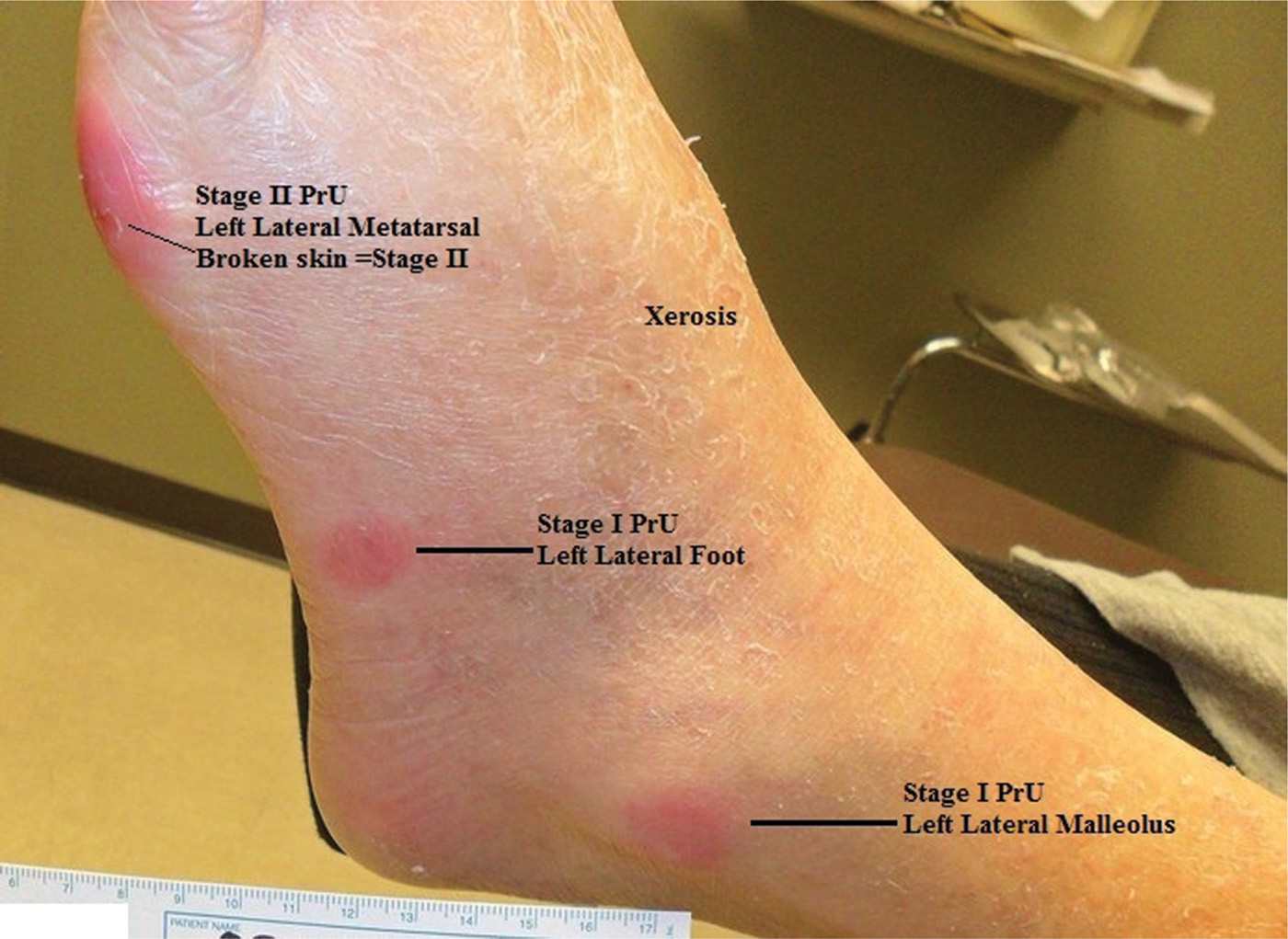

PrUs are defined as localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence as a result of pressure or in combination with shear and friction. Common locations for PrUs include the sacrum/coccyx, heels, buttocks, and the ischium (often called the sitting bones). The cellular death that can occur with pressure injury can be significant, and the damage incurred by the body can be very rapid and widespread.

Clinical Presentation

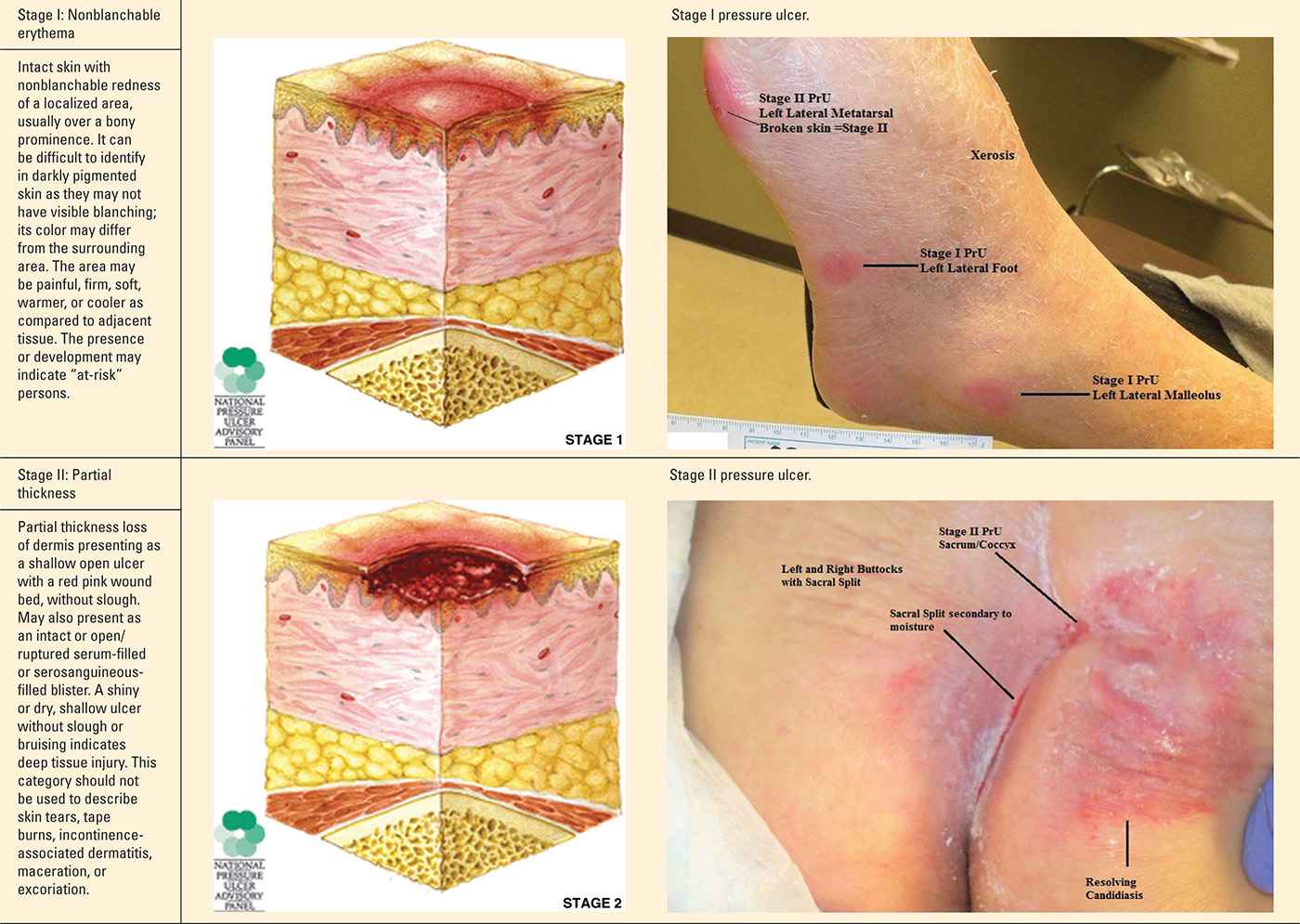

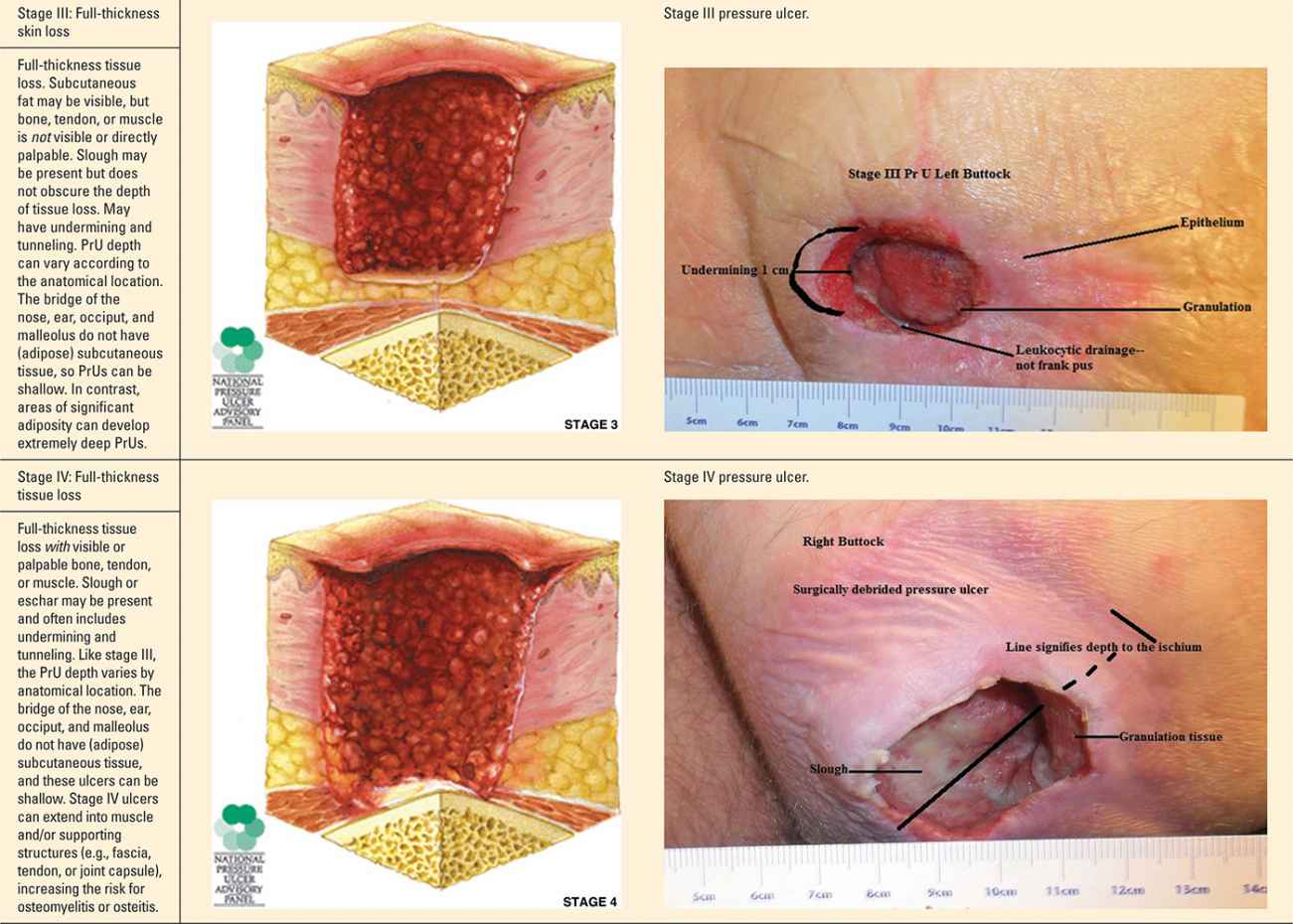

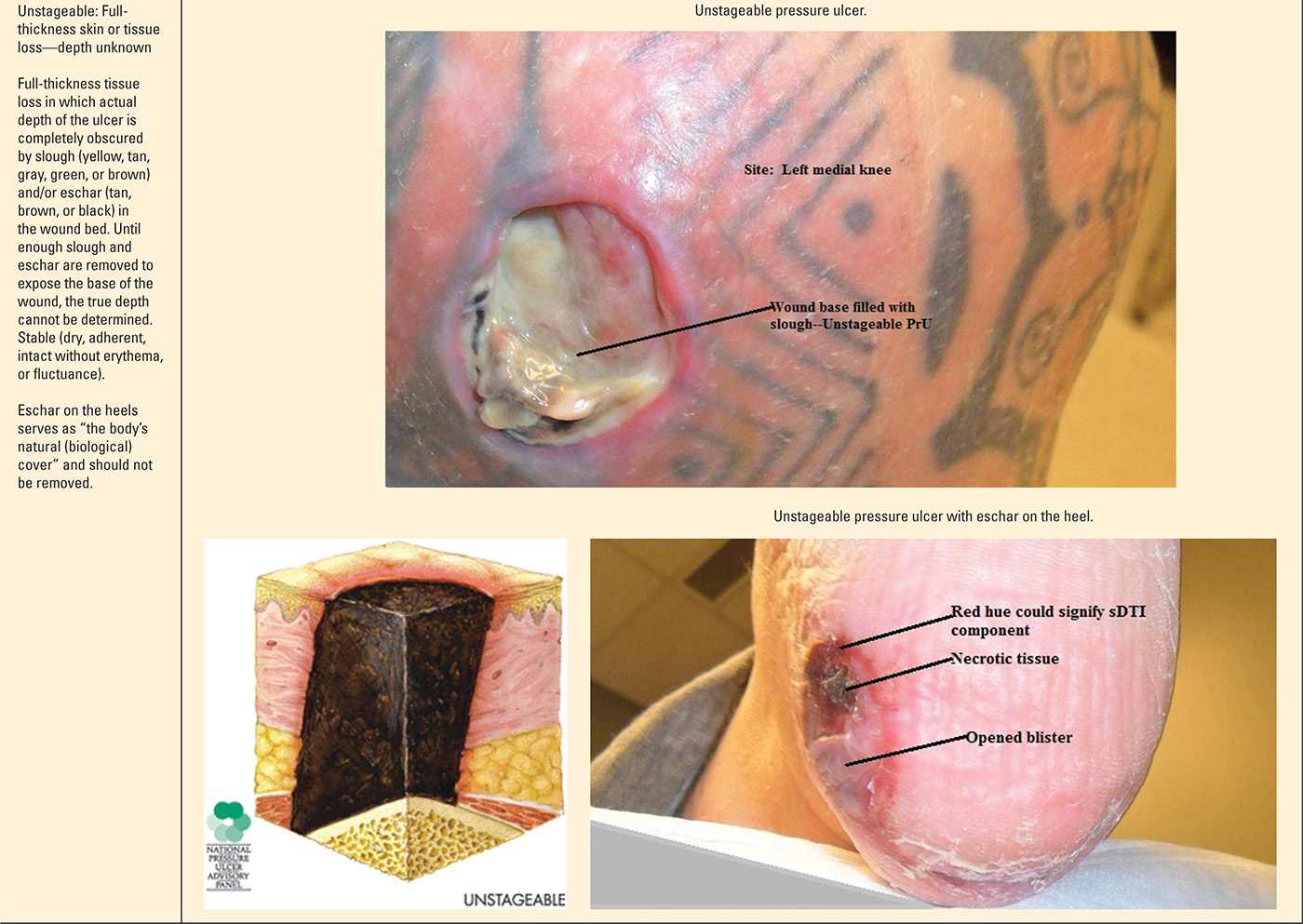

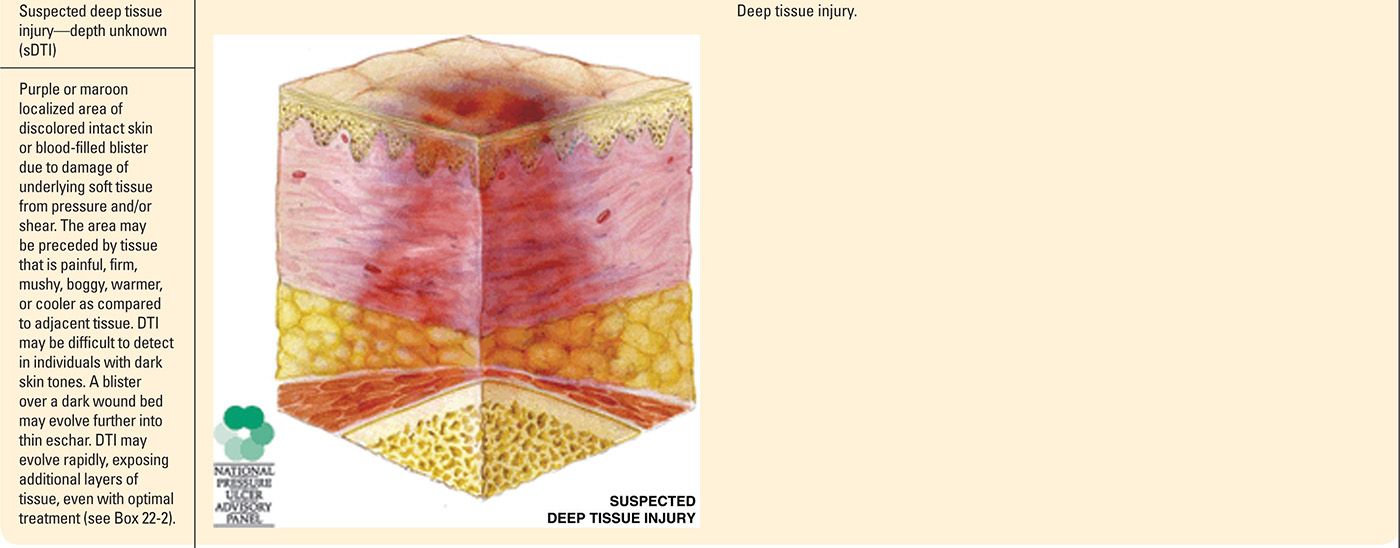

The staging and classification of PrUs provide a categorical approach to describing tissue destruction and clinical presentation. There are six stages or categories of injury, and the definitions are standardized (NPUAP, 2007). The staging of PrU can be complex. However, clinicians inexperienced with staging should take the purist approach—abide by the definitions and ensure your documentation of the wound supports the diagnosis (Table 22-1).

Pressure Ulcer Stages (Categories) |

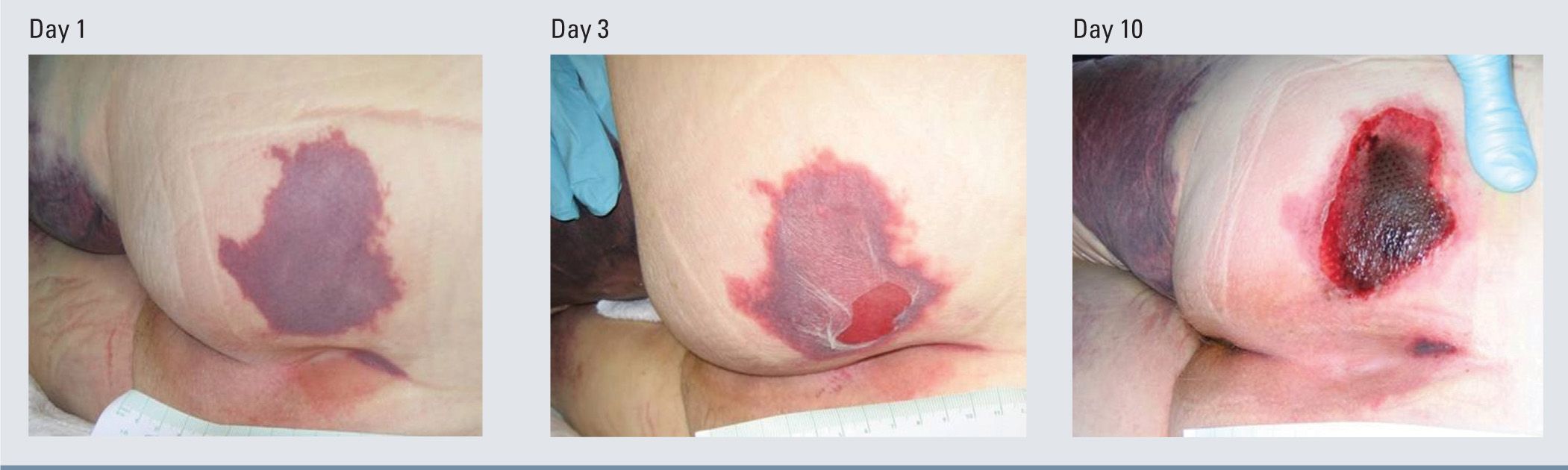

Progression of Suspected Deep Tissue Injury |

It is important to note that PrUs, while classified into stages, could present to the provider at any stage in the continuum. While the physiology and risk factors of PrUs are the same for any stage, clinicians may not see a stage I PrU prior to its advancement to a stage II PrU. Likewise, a PrU that presents as a sore and red area today could change and have a significantly different clinical presentation the next day. While there are limitations with the staging process, it can be very helpful in recognizing and guiding the management of a PrUs and sDTIs.

Management

Stage I pressure ulcers

When stage I PrUs are identified, it is important to consider the etiology—namely unrelieved pressure. Since individuals with one PrU are at increased risk to develop more, it’s important to consider pressure reduction both locally and globally. Optimal care of patients with a stage I PrU would include referral to a wound specialist/center. Yet primary care clinicians should develop management goals to reduce progression of the PrU, the development of new ulcers, and complications during the healing process.

The first and most important step in medical management is reducing/relieving the pressure (called “offloading”) to promote wound healing and prevention of new PrUs. Global pressure relief measures for PrUs can be ordered by the primary care clinician (e.g., a pressure-reducing mattress and/or chair cushion if they sit upright). Federal guidelines identify “group” surface for patients with staged PrUs (Box 22-3). Durable medical equipment (DME) companies are well versed and can help procure the necessary equipment to offload the patient. Patients may be eligible for a pressure-reducing mattress/hospital bed at home.

Whether lying in bed or sitting in the chair, frequent repositioning, definitely no less than at least every 2 hours, is essential. If the ulcer is on the dorsal surface of the body, consider side-to-side positioning rather than back-lying. If the ulcer has pressure on it when sitting, even with a pressure-reducing chair cushion, the patient’s sit time should be monitored. Consider a sitting restriction of no more than 2 hours up, and 2 hours in bed, as a rotation during awake hours.

Localized pressure relief measures for stage I PrUs are pressure reduction of the affected area (Figure 22-2). Consider practical measures such as elevation of heels. Try to avoid foam rings or doughnuts as pressure-reducing devices, because they concentrate the pressure to surrounding tissues rather than redistributing/reducing the pressure interface for the area. Positioning aids such as pillows or wedges or commercial heel offloading boots/devices might be useful.

Group Surfaces Criterias |

Group 1

Support surfaces are designed to either replace a standard hospital or home mattress or as an overlay placed on top of a standard hospital or home mattress. Products in this category include mattresses, pressure pads, and mattress overlays (foam, air, water, or gel).

Group 2

In addition to above, these powered air flotation beds, powered pressure-reducing air mattresses, and nonpowered advanced pressure-reducing mattresses

Group 3

Complete bed systems, known as air-fluidized beds, which use the circulation of filtered air through silicone beads

Topical therapies are not necessary for stage I PrUs. In fact, it was once thought that massage of the affected area would help to reestablish blood supply to the area. However, the current thinking is that massage to the area directly can actually cause more damage to occur and is no longer recommended. If the skin is scaly, a common problem with heel PrUs, for example, gentle application of a moisturizer may be warranted. In general, petrolatum is an effective moisturizer, but multiple compounds are on the market, including mixes of petrolatum and dimethicone, petrolatum and lanolin, and various natural moisturizers, which work as well.

Advanced pressure ulcers (stages II–IV)

The initial management of stages II, III, and IV PrUs is the same as that for stage I, in relation to offloading the pressure with surfaces and repositioning. Management decisions should be based on ulcer presentation. For example, a wound with cellulitis, bad odor, or frank pus may require a local or systemic anti-infective treatment. Advanced-stage PrUs require consultation and continuous care from a wound specialist, unless there is limited access.

Selection of dressings is based on the goal of care, and not on wound etiology. Palliative care goals involve comfort, while active care goals strive for wound healing. Stages III and stage IV PrUs may require packing to fill the void or “dead space” left from tissue destruction. Packing deep wounds is important to prevent infection and abscess formation. Presence of frank pus and odorous exudate demand microbiologic analysis. If palliation is the goal, less frequent dressing changes are preferred, in general. There are a variety of other complex treatment modalities available that would be best employed by the wound care specialist.

FIG. 22-2. Stage I pressure ulcer.

Nutritional screening should be performed on all patients with a stage II, III, or IV PrUs in addition to wound treatment. While visual examination of the patient may indicate general nutritional deficiencies, a thorough dietary assessment, as well as serum testing, is used to analyze the patient’s nutritional status. Patients with PrUs can have significant and undetected nutritional issues that impact their wound healing. It is considered a standard of care to assess the patient’s nutritional status, and it is imperative to incorporate this aspect of care into the wound treatment process. This is addressed at the end of this chapter.

Unstageable pressure ulcers

It is certainly possible to presume the depth of tissue injury, but technically, no classifiable stage can be determined until the wound base is visible. Treatment for unstageable PrUs should follow the same pathway as any advanced PrU, assuming the worst-case scenario of tissue destruction.

Suspected deep tissue injuries

Outpatient care to halt the progression of a suspected deep tissue injury (sDTI) is limited to simple pressure reduction (discussed above in PrUs) and protection of the area, using a “watch and wait” approach. Hospitalized patients and some wound care centers can offer low-frequency ultrasound therapy (LFUS), which can be beneficial in the treatment of sDTIs. Nutrition and overall health status must be assessed, and steps to intervene with comorbid factors should be implemented.

Topical ointments that contain trypsin and balsam of Peru may increase perfusion to the area applied but carry the risk contact dermatitis. These ointments act as a wound cover and protect the wound. Otherwise, protecting the wound with a soft dressing and changing one to two times per day would be indicated and may provide some relief to the patient. Systemic treatment for a sDTI is not indicated. However, primary care clinicians should address any and all confounding or comorbid conditions that may contribute to the delayed wound healing.

Referral and Consultation

Patients with an advanced PrU should be referred to the nearest wound care specialist. If the wound has necrotic tissue or exposed structures, consider surgical consult for debridement and potential skin graft/muscle flap. Some general and plastic surgeons can offer these services. Surgical consult should be sought as early as possible to prevent further complications such as sepsis, osteomyelitis (if not already present), and other complications. Optimal care of patient with an sDTI would include referral to a wound specialist or center who can provide other treatment modalities such as ultrasound.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Patients and caregivers should be educated and instructed about the importance of pressure redistribution and offloading. Follow-up visits for a stage I PrU highly depend on general patient condition. Patients at high risk to develop more PrUs warrant a follow-up in 1 to 2 weeks. However, changes in the patient’s condition should necessitate a call to you by the caregiver. Important changes include a break in the skin or the development of a blister in the area (both would upgrade the wound to stage II) or development of new PrUs, even if only stage I. These changes should prompt a patient referral for a wound specialist.

Advanced PrU patients living at home will need nursing care and possibly other services providing therapy. Facilitating this support is important for the patient, family, and caregivers, who may be overwhelmed in caring for their loved one. Feelings of guilt may arise if a loved one develops a PrU at home. Reassurance and education to caregivers may be needed, and should involve information regarding debility and its relationship to skin integrity failure.

As mentioned, patients with sDTIs are best managed and followed up by wound specialists. However, if none are available, the primary care clinician should monitor the patient weekly until the wound has stabilized and has declared to its fullest extent (meaning that the tissue destruction has stopped, and the wound now presents in the truest destructive form) and then every 1 to 2 weeks with coordinated care and support from home care and durable medical equipment resources.

VENOUS ULCERS

It is estimated that 500,000 to 600,000 people deal with venous leg ulcers (VLUs) each year in the United States. VLUs are the most common lower extremity ulcer, accounting for 80% to 90% of leg ulcers and frequently encountered in primary care practice. There are multiple causes of leg ulcers. Systemic diseases and conditions may present with cutaneous manifestations on the legs, including leukemias, syndromes, carcinomas, hematologic aberrancies, lymphatic abnormalities, and circulatory disorders (both venous and arterial). Often, leg ulcers have mixed etiologies, which makes for complex evaluation and management. For this chapter, focus will be on venous and arterial insufficiency.

Pathophysiology

VLUs are the result of venous insufficiency which is an impairment of the valves in the veins of the lower extremities. Insufficiency in the veins leads to pooling of blood in the lower extremities referred to as “stasis” or “venous stasis.” This malfunction causes tired, achy legs, dry skin, skin discolorations, skin texture changes, and ulcerations. Venous insufficiency is common in those who stand for long periods of time, are obese, have hypertension, and have vein varicosities and/or a history of superficial or deep vein thrombosis. Venous insufficiency can lead to chronic venous disease, commonly referred to as chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) or more recently as lower extremity venous disease (LEVD).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree