Medications are commonly prescribed by health care providers as part of the management of patient illness and wellness. Many individuals, especially the elderly, have multiple chronic diseases accompanied by a long list of drugs prescribed by various clinicians. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are common and can range from a mild exanthematous eruption to a potentially life-threatening condition. Nearly 100,000 deaths are attributed to ADRs each year in the United States. Cutaneous manifestations are frequently associated with an ADR and can provide clinical clues for early diagnosis and prompt management. Hence, clinicians must be mindful to consider the possibility of an ADR or side effect in patients presenting with skin eruptions.

This chapter will review the most common and important cutaneous eruptions associated with drug use and guide clinicians in the evaluation and treatment of these conditions. Urticarial drug eruptions and angioedema are discussed in chapter 16.

ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS

An ADR is an unintended and toxic response to a drug given for the purposes of prevention, diagnosis, or therapeutics (WHO, 2008). The reaction cannot be explained by another disease state or drugs and does not include drug abuse, overdose, withdrawal, or errors in administration. A serious ADR is considered one that results in death, disability, birth defect, or requires medical or surgical intervention (FDA, 2014). In contrast, side effects (SEs) are predictable and less toxic adverse effects that occur more frequently. SEs are usually dose related.

Risk Factors

Multiple factors place an individual at increased risk for developing an ADR including the drug itself. Clinicians should maintain a heightened awareness when their patients are receiving medications that are known to be high risk for ADR. Overall, aminopenicillins, sulfonamides, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) account for the largest number of drug-related cutaneous eruptions. Other risk factors include the following:

• Host. The elderly are at greater risk for ADRs that may be attributed to polypharmacy and changes in drug metabolism and/or excretion with aging. Children are also at higher risk due to their smaller body size. Females are affected more than males, and individuals with a history of an ADR have an increased risk of developing one to another medication.

• Immune status. Patients who are immunosuppressed, have HIV, or have malignancies such as lymphoma have an increased risk for ADRs, the degree of which may correlate with the severity of their disease state.

• Genetics. There is an association with HLA types present in identified races that predispose them to an ADR induced by a specific drug like phenytoin, carbamazepine, allopurinol, sulfamethoxazole, and abacavir. Patients with a history of an ADR may have family members who may not be able to metabolize that drug or tolerate its metabolite.

• Medications. The drug itself may have factors that increase the risk for an ADR, including the class of drug, dose, route of administration, and drug–drug interactions.

• Infection. Patients are at greater risk of developing a hypersensitivity reaction during viral illnesses. The most well-known example is an ampicillin-induced rash in patients with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) or a trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced rash in patients with HIV. Drugs can also trigger latent viral infections.

Pathophysiology

ADRs are classified as immunologic, nonimmunologic, or idiosyncratic. It is helpful to recognize the type so that appropriate treatment may be initiated and future reactions avoided.

Immune-mediated reactions

Most ADRs are an immunologic response to a drug and considered a hypersensitivity reaction (see chapter 16). Cutaneous ADRs can be classified as type I to IV reaction patterns:

• Type I (immediate): IgE mediated, occurs within minutes of ingesting medication. ADRs include urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis.

• Type II: IgG mediated and cytotoxic. Examples would include drug-induced hemolytic anemia or pemphigus.

• Type III: antigen–antibody complexes deposited in skin and vessels. The onset is minutes to days after ingestion. ADRs include serum sickness, urticarial vasculitis.

• Type IV (delayed): sensitized T cells with four subtypes. This is the most common type of ADR and typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks after initiation of the suspected culprit drug. Type IV hypersensitivity ADRs include Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), contact dermatitis, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

Nonimmunologic reactions

High drug doses or overdosage, as well as undesirable drug SEs (i.e., chemotherapy), can illicit non-immune-mediated cutaneous reactions. Extended therapy on a medication may result in cumulative toxicity to the drug or its metabolites which may be an immediate (i.e., amiodarone) or delayed (i.e., arsenic) reaction. Drug–drug interactions can also occur via numerous mechanisms including the displacement of medication from binding proteins or receptor sites (i.e., tetracycline and calcium). As mentioned, drugs can alter the metabolism of other drugs or metabolic changes within the body. And lastly, drugs can exacerbate a disease or trigger a latent disease process (i.e., lithium and psoriasis).

Idiosyncratic reactions

When an ADR cannot be attributed as an immunologic or nonimmunologic reaction, it is considered idiosyncratic.

History

The diagnosis of a cutaneous ADR is based on clinical suspicion, presentation, chronology, and probability. The most important factor in the diagnosis of an ADR is the history and timing of the intake of the suspected drug. A detailed history of all prescription, nonprescription, and recreational drugs taken by the patient must be collected; however, it can be a lengthy process especially in the elderly where polypharmacy is common. It can be helpful to inquire about all routes of administration when accounting for their medications (Box 17-1). The chronology is critical to identifying the causative agent of an ADR, including date of initiation, dosage, and first sign of the reaction. And a family history of ADRs should be noted, given the genetic associations that have been observed.

Clinical Presentation

Physical examination findings often mimic other skin disorders and may occur days or even years after beginning drug therapy, making the diagnosis challenging. An important variable that impacts the quality of the physical assessment is a complete body examination. Often, patients perceived their “rash” to be independent of any other symptoms or lesions occurring on other parts of their body (see chapter 1).

A detailed physical examination should be performed carefully, making note of the primary morphology and distribution of the cutaneous symptoms. Close examination of the oral cavity and other mucous membranes is extremely important. Vital signs should be taken to assess for fever, hypotension, tachycardia, and other systemic symptoms signaling a possible life-threatening ADR.

Diagnosis of a cutaneous ADR eruption is based on clinical suspicion, chronology, and probability. Clinicians should always consider drug eruption in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with pruritic, symmetrical, and generalized skin rashes. There are several valuable resources and online databases available, such as Litt’s Drug Eruption Manual (2009), which can enable clinicians to view specific drug information, reaction, and incidence. It also provides content regarding the most common drug eruptions and patterns that can aid in predicting, diagnosing, and managing the patients with suspected ADRs.

Diagnostics

Most ADRs are diagnosed based on history and physical findings and do not require any diagnostics. In severe or persistent cases, further testing may be necessary. Skin biopsy may be indicated to support the clinician’s suspicion and to rule out other disease processes. Histologic findings typically show spongiosis with perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes and eosinophils, and require clinicopathologic correlation. Patients and clinicians must understand that even if histology supports the diagnosis of an ADR, it cannot identify the offending agent. This is a patient expectation that should be discussed and managed before a biopsy is performed. Immunofluorescence is performed when a connective tissue disease or autoimmune blistering disease is suspected.

The Seven “I”s for History of Patient Medications |

Instill (eye, ear drops, contact lens solution)

Ingest (capsules, tabs, gels, liquids)

Inhale (cortico steroids)

Inject (IM, IV, SC)

Insert (suppositories)

In secret (sharing among elders or teens)

Intermittent (not taken every day)

Approach to Identifying Cause of Adverse Drug Reaction |

1. Identify the morphology, distribution, and location for a clinical pattern

2. Assess for signs and symptoms of systemic organ involvement

3. Determine any/all medications that have been ingested

4. Establish an accurate chronology of medication intake; create a timeline

5. Inquire about a personal and family history of prior ADRs

6. Determine the probability of ADR

7. Consider a nondrug etiology

8. Discontinue the suspected offending drug

9. Consider additional labs or biopsy, if indicated

10. Educate the patient that the ADR will not resolve immediately

11. Ensure the patient understands importance of documenting the allergy

12. Consider rechallenge at a later date, if appropriate

Other diagnostics including laboratory studies are indicated in patients with systemic symptoms. In addition to a complete blood count with differential and chemistry panel, antinuclear antibodies (ANA) screening can be helpful. Antihistone antibodies may support a diagnosis of drug-induced lupus. Blood cultures, urinalysis, and stool guaiac will help to rule out infection and vasculitis. Provocation testing is only considered in specific circumstances and is generally performed in carefully controlled settings.

Management

Management of an ADR is relative to the specific drug and reaction type which will be discussed in this chapter. However, the first and universal approach to all ADRs is discontinuation of the offending drug (Box 17-2).

Patient Education and Follow-up

Regardless of the type of drug eruption, any patient diagnosed with an ADR must be educated about lifelong avoidance of the offending drug, medications in the same drug class, or other classes that may have potential cross-reactivity. Good communication between the patient and health care team should ensure that all personal health records and medic-alert identifiers reflect the patient’s history of serious ADRs. Most importantly, patients with an ADR should be instructed to notify their health care provider should the rash recur or worsen, indicating a severe hypersensitivity reaction. Clinicians should be alerted if the patient develops fever, redness that starts to expand over the body, blisters, ulcerations, or sores on any mucous membrane, or the patient experiences a new onset of pain. In the event that the provider is unavailable, the patient should be referred to the emergency department (Box 17-3).

CUTANEOUS DRUG REACTION PATTERNS

ADRs are often described by the pattern of symptoms, morphology, distribution, and/or underlying etiology. The spectrum of clinical presentations can be categorized into one of the following patterns: exanthematous, fixed drug, bullous, neutrophilic, acneiform, drug-induced lupus, photosensitivity, and pigmentary eruptions. The reaction pattern can aid in the diagnosis as many drugs are known for specific reaction patterns.

Red-Flag Symptoms for Systemic Involvement in Adverse Drug Reaction |

Fever

Purpura

Erosions/blisters of mucosal membranes

Angioedema

Erythroderma

Blisters (especially positive Nikolsky sign) or necrosis

Facial edema

Lymphadenopathy

Chest pain or dyspnea

Meningism

Arthralgia

EXANTHEMATOUS DRUG REACTIONS

Exanthematous drug eruptions account for about 95% of all drug reactions. As the name implies, exanthematous eruptions are maculopapular or morbilliform (measle-like in appearance) and are often difficult to distinguish from viral exanthems such as EBV, enterovirus, adenovirus, acute HIV, HHV-6, parvovirus (Box 17-4).

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of these reactions is unknown, but it is believed to represent a type IV hypersensitivity reaction characterized by a T-cell-mediated response, causing direct cellular damage.

Drugs Frequently Implicated in Exanthematous Drug Reactions |

Allopurinol

Amoxicillin

Ampicillin

Cephalosporins

Barbiturates

Captopril

Enalapril

Carbamazepine

Chlorpromazine

Diflunisal

Gentamycin

Gold salts

Glipizide

Glyburide

Isoniazid

Lithium

Naproxen

Penicillin

Phenothiazines

Phenylbutazone

Phenytoin

Piroxicam

Quinidine

Sulfonamides

Thiazides

Thiouracil

TMP/SMX

Adapted from Habif, Clinical Dermatology (2010).

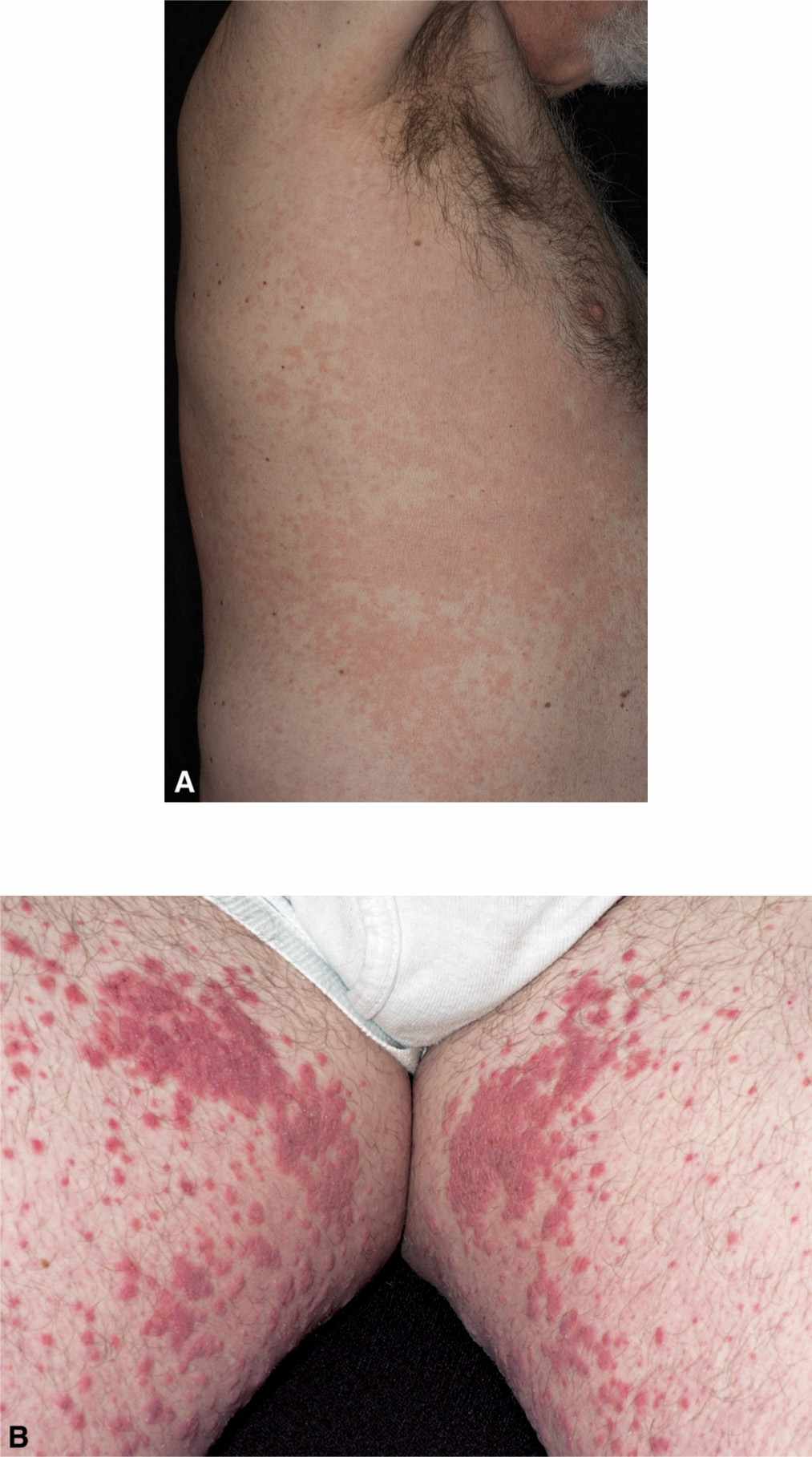

Clinical Presentation

The onset of exanthematous ADRs usually occurs within hours to weeks after initiation of the drug. They generally develop as bright red, pruritic macules and papules that symmetrically appear on the trunk but may coalesce and spread to the extremities (Figure 17-1A). In adults, it usually spares the face, whereas in children, it may be limited to the face and extremities. Confluent lesions may develop bilaterally (Figure 17-1B) and in the intertriginous areas. Palms, soles, and mucous membranes can be involved. The associated pruritus often disturbs sleep. A low-grade fever and/or chills may be present compared to the high-grade fever associated with a hypersensitivity syndrome reaction. The onset of exanthematous eruptions usually occurs within hours to weeks after initiation of the drug.

FIG. 17-1. A: Exanthematous eruption. B: Exanthematous eruption coalescing plaques.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Exanthematous adverse drug reaction |

• Viral exanthem

• Scarlet fever

• Acute graft-versus-host disease

• Kawasaki disease

• Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

• Secondary syphilis

• Systemic juvenile arthritis (Still disease)

• Disseminated allergic contact dermatitis

• Urticaria

Diagnostics

An exanthematous drug eruption is usually a clinical diagnosis that correlates with a history of drug administration. In most cases, it is not necessary to perform a skin biopsy except when the diagnosis is in question or to rule out other causes. Histopathology typically shows eosinophilia, perivascular lymphocytes, and vacuolar if the patient interface dermatitis. If the patient’s morbilliform rash progresses or if the patient develops fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, or angioedema, additional diagnostics would be indicated for evaluation of systemic involvement.

Management

In addition to discontinuing the suspected drug, symptomatic treatment is all that is needed for a mild or moderate exanthematous drug eruption. Antihistamines, both H1 and H2 blockers, may be used to reduce pruritus. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used during the acute phase, if necessary. Since this eruption is often widespread, triamcinolone 0.1% cream or ointment, prescribed in a large quantity (1-lb jar), is usually sufficient but should be avoided on the face, skin folds, and genital areas (see chapter 2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree