Patients often seek evaluation of their nevi (often referred to as moles by patients) because of a concern for possible malignancy or disconcerting appearance. Primary care clinicians are strategically positioned to assess skin lesions not only when it is the patient’s chief complaint but also during office visits for other health concerns. Skin examinations, integrated into patient visits, are opportunities for early recognition and treatment of skin cancer. The simple practice of having patients remove their shirt when listening to lung sounds can provide the clinician with the opportunity to visualize their back, one of the common areas for melanoma.

The examination of a patient with numerous pigmented lesions can be challenging for both novice and experienced clinicians. There are multiple tools and common characteristics that can help health care providers discern benign lesions from those that warrant further investigation. For lesions that do suggest possible pathology, this chapter will address the various sampling techniques and initial interpretation of the pathology report.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PIGMENTED SKIN LESIONS

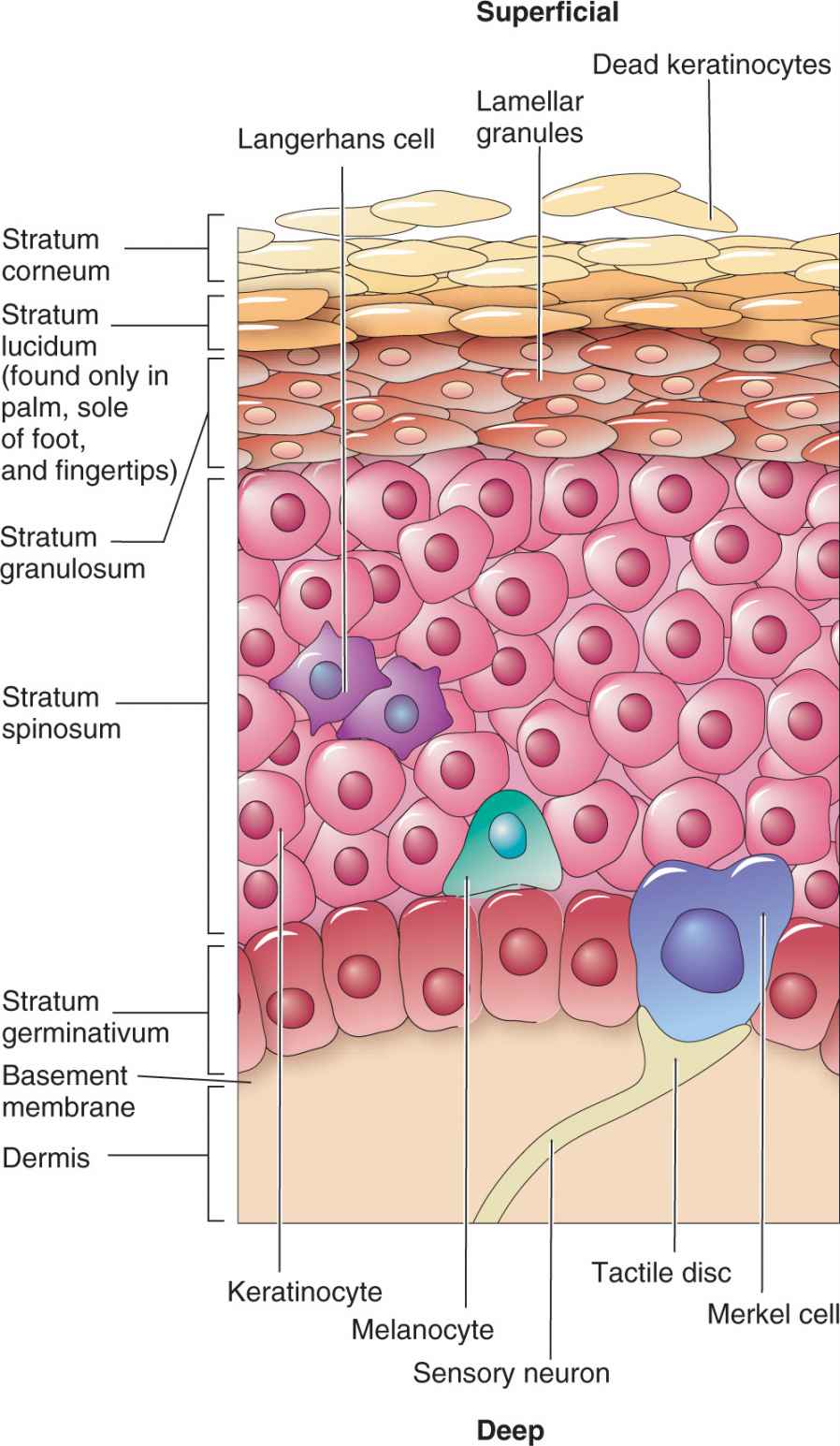

Pigmented skin lesions are due to melanocytes that develop from dendritic cells in the neural crest of the embryo and migrate to the epidermis. Melanosomes, contained in the melanocytes, produce melanin, which provides the skin with its color. There is about one melanocyte for each ten basal keratinocytes (Figure 7-1). Variation in the color of skin among races is due to the size and distribution of melanosomes, not number of melanocytes. Individuals with dark skin have larger melanocytes that are distributed more linearly along the basement membrane. Likewise, light-skinned people have smaller-sized melanocytes which are clustered together as well as containing less melanin.

Exposure to both natural and artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVR) increases the production of melanin, which results in larger melanocytes, giving lighter skin a tanned appearance. Other physiologic variables that influence the production of melanin include estrogen and progesterone. This can be seen with patient complaints of darkening nevi or melasma during pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, and use of oral contraceptives.

Melanin also has a protective function as it both absorbs and scatters UVR, which protects the keratinocytes from DNA mutation that can lead to oncogenesis. This small measure of protection (about SPF 4) contributes to the social practice of going to tanning beds to acquire a “base tan” before vacation. This creates a challenge for clinicians in teaching patients about the increased skin cancer risk from UVR for all types of skin.

BENIGN PIGMENTED LESIONS

Patients seek care from both primary care and dermatology providers for the complaint of a changing nevus. Often the patient reports that a nevus has raised, developed hair, changed color, or become speckled. They rely on the clinician’s assessment to reassure them that it is benign or proceed with appropriate diagnostics if it is suspicious for malignancy. However, all “brown spots” are not nevi, and understanding the pathophysiology and risk for malignancy of pigmented lesions can improve the clinician’s accuracy for risk, diagnosis, and patient satisfaction.

Epidermal Melanocytic Neoplasms

Most pigmented epidermal lesions are benign and have a vast variation in clinical presentation. The characteristics of lesions are based upon the number, size, amount of melanin, and distribution of the melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).

Lentigos

Lentigines (the plural of lentigo and pronounced len-tij´ĭ-nēz) present as pigmented macules that have an increased number of melanocytes or increased amount of melanin. Despite their benign pathology, patients may request treatment to minimize their appearance. They occur in a number of different clinical forms.

Ephelides, commonly known as freckles, are characterized by hyperpigmented brown macules found on sun-exposed areas during childhood. The number of ephelides usually increases with sun exposure in the summer and may almost completely fade during the winter. They are due to an increase in size of the melanocytes, not number of the melanocytes, and are evidence of UVR damage (Figure 7-2).

Lentigo simplex is larger and darker than an ephelides and can also appear during childhood. They are not affected by sun exposure and therefore do not fade in the winter months. A lentigo simplex can occur anywhere on the body as solitary, hyperpigmented brown 0.5- to 1.5-cm macule. They are characterized by an increased number of melanocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction. These benign lesions require no treatment (Figure 7-3).

Solar lentigines are a common response to sun exposure in fair-skinned, blue-eyed, and blonde or red-haired individuals. Like ephelides, their onset is during childhood and they are distributed in large numbers (sometimes coalescing) in sun-exposed areas of the face, neck, shoulders, arms, and dorsal hands (Figure 7-4). Unlike ephelides, these do not fade when the patient stays out of the sun. Pigmentation is the result of increased melanin production due to prolonged UV exposure. Treatment is not necessary unless the patient is seeking cosmetic improvement, which can be difficult if they are extensive. A clinical skin examination should be performed to identify abnormal lesions or “ugly duckling” amid the solar lentigines.

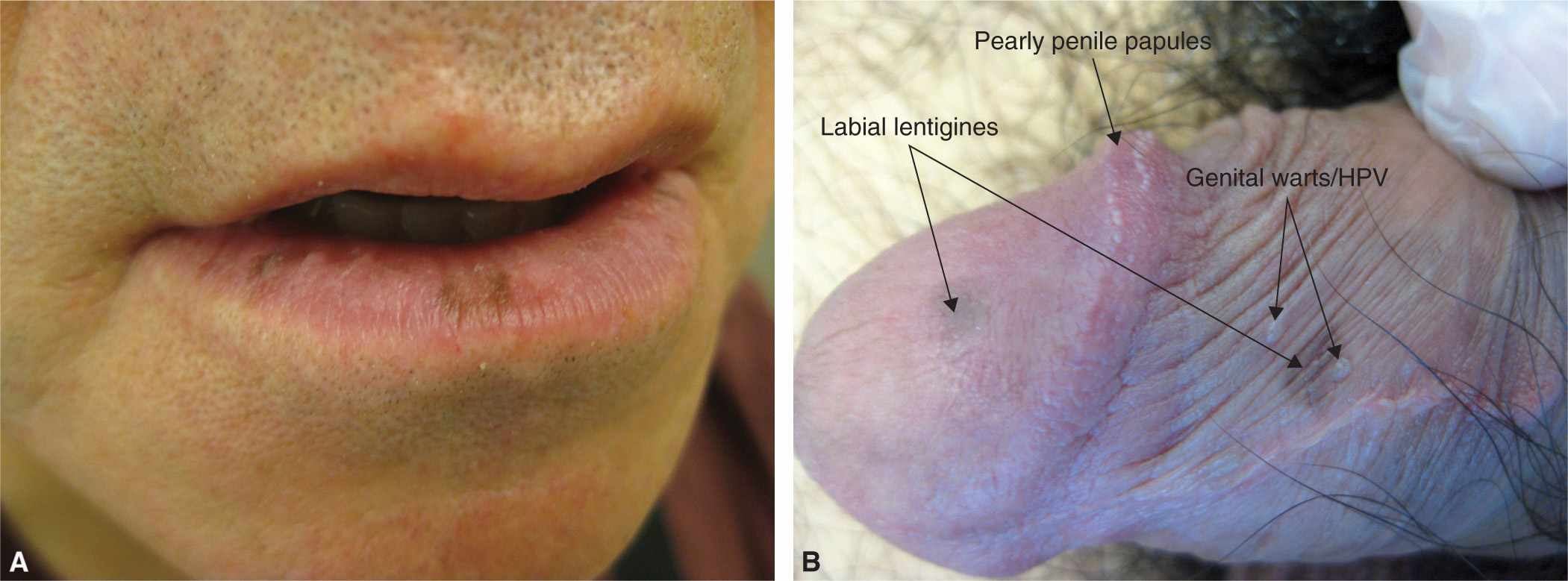

Labial, penile, and vulvar lentigines are a proliferation of melanocytes, with an increase in the number of dendrite melanocytes, which are different from the melanocytes found in typical keratinocytes. These lentigines occur on the labia, vulva, mucosa of the lips and glans penis. Solitary lesions are usually not concerning and require no treatment (Figure 7-5). However, numerous hyperpigmented brown macules noted on the lips, mucosal surfaces, and genitalia, should alert the clinician for potential Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (Figure 7-6). Patients diagnosed with this syndrome during childhood are at higher risk for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas and breast and ovarian cancers.

FIG. 7-1. Anatomy of the epidermis and location of melanocytes.

FIG. 7-2. Ephelides or common freckles are the result of UVR exposure and usually fade in the winter.

FIG. 7-3. Lentigo simplex.

FIG. 7-4. Solar lentigines from sun exposure do not fade in the winter. Noted “ugly duckling” lesion upon examination.

Café au lait macule

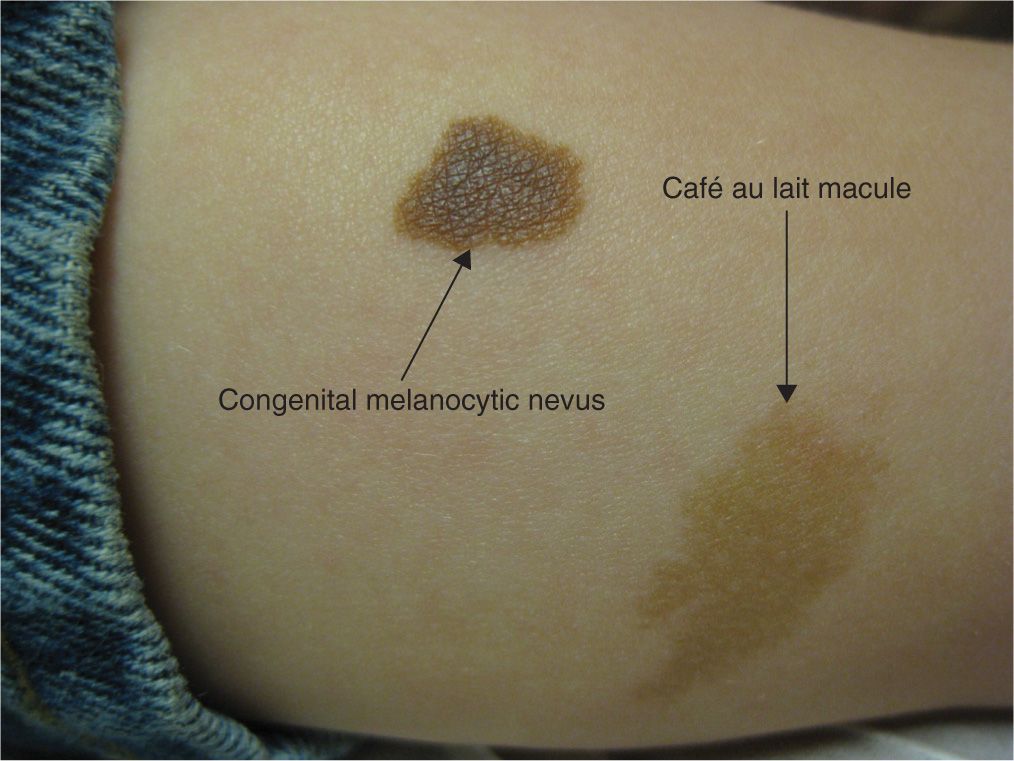

These uniformly pigmented, light brown macules and patches are known as café au lait lesions and typically appear at birth or during infancy. They are usually flat, ovoid in shape, and lighter brown than congenital nevi (Figure 7-7). Twenty percent of the population has one café au lait macule, which is considered normal. Multiple café au lait macules, however, can be associated with the autosomal dominant genodermatoses, neurofibromatosis type 1 and type 2 (NF1 and NF2, respectively). A full skin examination should be performed to assess for the number and size of café au lait macules/patches, presence of neurofibromas and axillary freckling. Patients with clinical presentation suspicious for NF1 or NF2 should be referred for neurologic and developmental evaluation (see chapter 6). In adults, a full skin examination should be performed for skin cancer screening.

FIG. 7-5. A: Labial lentigines more common on the lower lip. B: Penile lentigines in addition to pearly penile papules and HPV.

FIG. 7-6. Orolabial lentigines suspicious for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

FIG. 7-7. Comparison of a café au lait macule beside a small congenital melanocytic nevus.

Nevus spilus

Nevus spilus is a congenital epidermal nevus with an appearance similar to a café au lait. It typically presents in infancy as a light brown patch with darker hyperpigmented brown macules or speckles (also called speckled lentiginous nevus) within the lesion. Most are located on the trunk or lower extremities and are benign (Figure 7-8).

Becker’s nevus

A Becker’s nevus (Becker’s melanosis) is typically a very large, light brown to tan patch with or without an increased amount of darker hair growth. The most common location is on the shoulders, upper chest, or back, becoming more evident during adolescence, with a higher incidence in males. Becker’s nevi are epidermal nevi involving keratinocytes, hair follicles and melanoctyes. They are usually unilateral and may be associated with ipsilateral hypoplasia of breast and skeletal anomalies, including scoliosis, spina bifida occulta, or ipsilateral hypoplasia of a limb (Figure 7-9).

FIG. 7-8. Nevus spilus.

FIG. 7-9. Becker’s nevus classic presentation on the shoulder or upper chest.

Dermal Melanocytic Neoplasms

Mongolian spots

Commonly located over the sacrum of infants, Mongolian spots are dark blue-brown patches that occur in infants usually with dark skin tones. The hyperpigmented blue color is from elongated melanocytes, giving the patch the appearance of a bruise. Given the location of the lesion and bruise-like appearance on an infant or child, many providers have mistaken this for a sign of child abuse (Figure 7-10). They are benign and usually fade significantly by adulthood. It is uncommon, but possible for adults to develop this type of dermal melanocytosis (Figure 7-11).

FIG. 7-10. Dermal melanocytosis or common Mongolian spot commonly located over the sacrum.

FIG. 7-11. Less common dermal melanocytosis in a Caucasian adult.

Nevus of Ota and Ito

Nevus of Ota is oculodermal melanocytosis. It is thought to be due to the failure of the melanocytes to migrate from the dermis up to the epidermis during embryonic development. Patients present with a dark blue hyperpigmented patch, usually with a unilateral distribution along the trigeminal nerve (V1 and V2 branches). The underlying mucosa, conjunctiva, and tympanic membranes may be also be pigmented and may darken with age. There is an increased prevalence in women and Asian, African American, and Indian races (Figure 7-12). The less common nevus of Ito is similar, but involves the lateral supraclavicular or lateral brachial nerve distribution. Like any pigmented lesion, these should be monitored for signs and symptoms of melanoma. Glaucoma has been associated with nevus of Ota. Although usually benign, these lesions can have a psychological impact on the patient’s body image. Camouflage makeup is often used, but topicals have no effect. Q-switched laser, requiring repeated treatments, provides the most promising cosmetic results.

FIG. 7-12. Nevus of Ota.

Lesion Characteristics in Nails That Should Raise a Red Flag |

![]() Location: Single digit, thumb, or great toe nails

Location: Single digit, thumb, or great toe nails

![]() Appearance: Fast growth, longitudinal melanonychia, band width more than 3–5 mm

Appearance: Fast growth, longitudinal melanonychia, band width more than 3–5 mm

![]() Hutchinson’s Sign: Periungual pigmentation of skin

Hutchinson’s Sign: Periungual pigmentation of skin

![]() Nail Dystrophy: Notch in free distal nail margin, surface irregularity, oozing, or bleeding lesion similar to ingrown nail

Nail Dystrophy: Notch in free distal nail margin, surface irregularity, oozing, or bleeding lesion similar to ingrown nail

Melanonychia striata

Brown longitudinal stria (plural is striae) that occurs in the nail is called melanonychia striata. This can be a normal variant that is common in patients with darker skin and is typically consistent pattern present in several nails. The streak of pigmentation is thin, uniform, and does not involve the nail folds. Clinicians should carefully assess all nails for atypical features that may indicate a developing periungual melanoma and prompting a referral to a dermatologist for evaluation (Box 7-1).

Melanocytic Nevi

Pigmented nevi are composed of nevus cells (nevocytes) that are derived from melanocytes located in nests near the DEJ. Nevocytes are similar to melanocytes, but are nondendritic cells and larger in size. Some nevus cells remain at the DEJ while others eventually migrate down into the dermis, accounting for some of the normal physiologic changes that can occur throughout the life span. And since most common nevi have a very low risk for malignancy, understanding the normal characteristics and evolution of nevi can reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies on benign nevi, which can be costly, scarring, and stressful for patients. It can also help assist the clinician to recognize atypical features or suspicious symptoms indicating risk for melanoma and necessitate a biopsy.

Ways to Classify Melanocytic Nevi |

Onset

![]() Congenital: present at birth or soon thereafter

Congenital: present at birth or soon thereafter

![]() Acquired: occurs after 6 months old

Acquired: occurs after 6 months old

Location of Nevus Cells

![]() Epidermal: arising in the epidermis only

Epidermal: arising in the epidermis only

![]() Junctional: arising at the dermal–epidermal junction

Junctional: arising at the dermal–epidermal junction

![]() Dermal: nests in the dermis or subcutaneous fat only

Dermal: nests in the dermis or subcutaneous fat only

![]() Compound: a combination of junctional and dermal

Compound: a combination of junctional and dermal

Type of Cells

![]() Melanocytic: melanocytes only

Melanocytic: melanocytes only

![]() Spindle cell: spindle-shaped cells as in Spitz nevus

Spindle cell: spindle-shaped cells as in Spitz nevus

![]() Blue pigmented cells: Cellular blue nevi

Blue pigmented cells: Cellular blue nevi

The subtypes of nevi can be classified in several ways, including onset of the lesion, location of the nested cells, and type of cells (Box 7-2). There can be an overlap in the classification of the same lesion. For example, an intradermal nevus is an acquired nevus located in the dermis. Nonetheless, these categories can help you understand the pathophysiology and clinical presentation.

Congenital nevi

Nevomelanocytes clustered in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous that appear at birth, or within the first 6 months of infancy, are called congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN; Figure 7-13). CMN occur in approximately 2% to 6% of newborns and have been historically categorized according to the predicted adult size (PAS). This has guided clinicians in anticipating the risk for malignancy and management options (Table 7-1).

Although all CMN have the risk of developing melanoma, small- and medium-sized lesions carry the lowest risk (<1%), which would most likely occur after puberty. In contrast, large (also called giant or garment) nevi have an estimated lifetime risk of up to 5%, with half of these melanomas occurring before the age of 5 years. Yet many experts argue that lesion characteristics, in addition to size, should be considered in the classification criteria and ultimately risk stratification. Krengel et al. (2013) proposed new criteria in hopes of providing a better prognostic tool to measure risk and guide care. Lesions characteristics were added to the classification system as variables influencing risk for malignancy (Box 7-3). The stratification of CMN sizes was also expanded to include a separate “giant size” category. Large CMN overlying the spinal column and skull have been associated with neurocutaneous melanocytosis (NCM) with symptoms of increased cranial pressure, vascular birthmarks, spinal cord compression, tethered spinal cord, or leptomeningeal melanoma.

FIG. 7-13. A: Child with medium-sized CMN on the lip and chin of infant with significant cosmetic impact. B: Medium CMN.

Risk Stratification Based on Size of Congenital Melanocytic Nevi |

| SIZE OF LESION | MANAGEMENT |

Small

| <1.5 cm diameter | Greatest risk for malignancy occurs after puberty If no atypical features: Routine prophylaxis excision is controversial Regular self skin checks—ABCDEs Annual clinical examinations or with any changes Documented baseline photo of lesion UVR avoidance and protection Elective excisions can be delayed until puberty If any concern: PCPs may monitor small lesions if they are confident in their skin assessment skills Refer to a dermatologist for regular monitoring or biopsy of medium lesions, atypical symptoms, or if PCP is unsure |

Medium

| ≥1.5 to 10 cm diameter |

|

Large/Giant

| >20 cm or ≥10% BSA | Greatest risk for malignancy occurs before puberty Refer immediately to dermatologist: If located over head or spine due to increased risk for neurocutaneous melanocytosis Coordination of care with a neurologist, plastic surgeon, and other specialists Counseling patient and parents Lifelong monitoring and UVR avoidance |

PCP, primary care provider; UVR, ultraviolet radiation

Modified from Kopf, A.W., Bart, R.S. & Hennessey, P. (1979). Congenital Nevocytic nevi and malignant melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 1(2), 123–130.

Proposed Characteristics of Congenital Melanocytic Nevi That Increase Risk for Malignancy |

Size

Number of medium CMN

Location

Number of satellite nevi by 1 year of age

Heterogeneity of color

Rugosity

Hypertrichosis

Extensive nodules

Adapted from Krengel, S., Scope, A., Dusza, S.W., Vonthein, R., & Marghoob, A. A. (2013). New recommendations for the categorization of cutaneous features of congenital melanocytic nevi. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 68(3), 441–451.

Clinical Presentation

The initial presentation of small or medium CMNs can be varied from pink to dark brown and with some color variation including speckled appearance. They are usually well circumscribed and may have hypertrichosis. As the child ages, CMNs commonly rise into a plaque. Large CMNs may develop a cobblestone surface with color variation. Garment or bathing suit nevi may involve any area of the body and have a dermatomal distribution. A segmental or circumferential distribution can be associated with underlying musculoskeletal abnormalities.

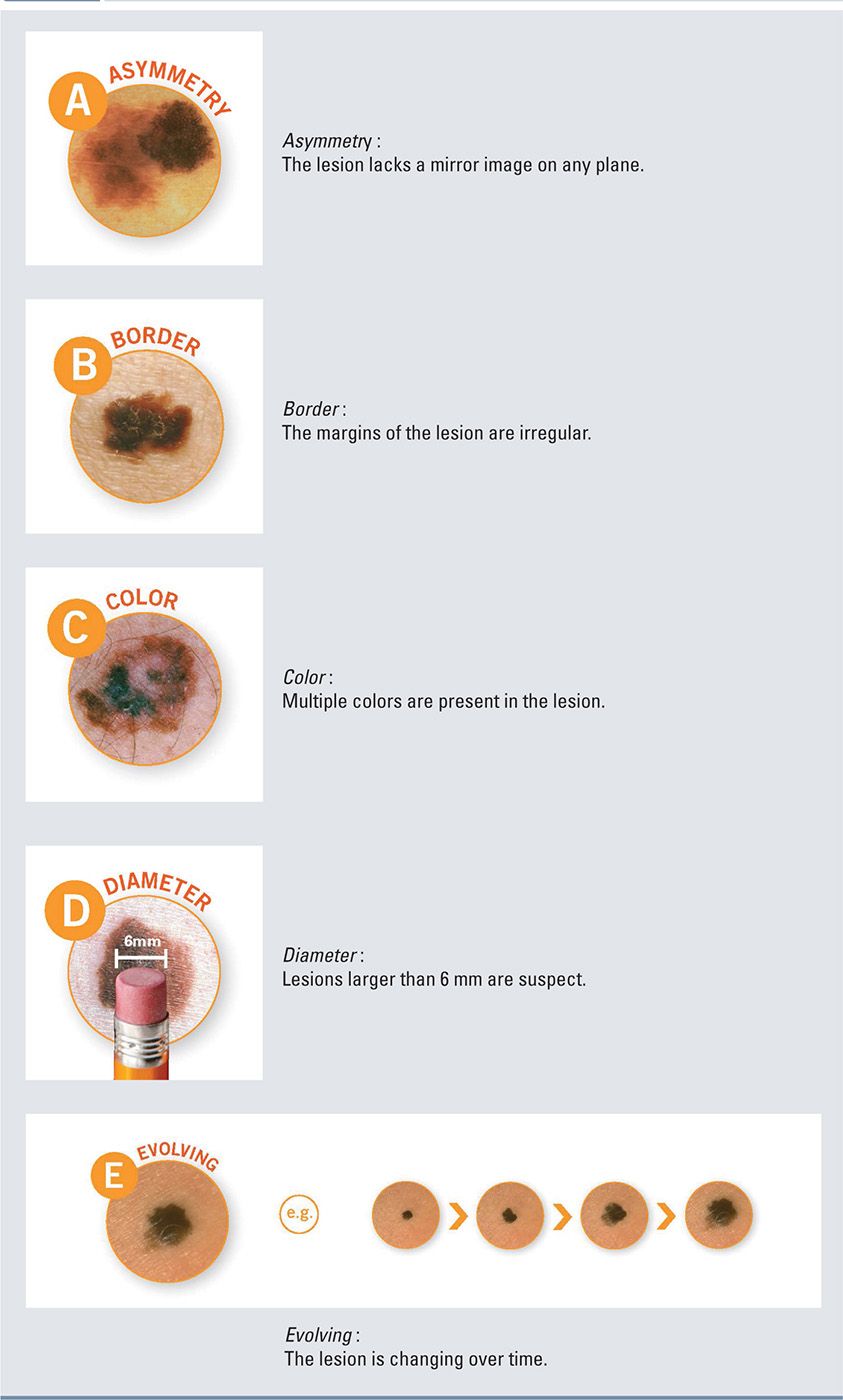

All CMNs, like any pigmented lesion, should be assessed for clinical characteristics of melanoma using the classic ABCDE checklist (Box 7-4). The common variation of color and irregular borders of large and giant CMN can make this risk assessment very complex. Additionally, particular attention should be given to the development of satellite lesions, nodularity, and ulceration.

ABCDE Checklist for Lesion Characteristics of Melanoma |

Diagnostics

Primary care clinicians should document the specific characteristics of any congenital nevus during the physical exam of a newborn or child. The size, number and location of each lesion should be noted. The PAS should be estimated since the lesion grows proportionately with the patient into adulthood and stratifies the patient risk for melanoma. To calculate the PAS, multiply the diameter of the lesion (in millimeters) by 2 if it is located on the head, or 3 if it is on the trunk. This determines the size for classification.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree