Patients frequently present to primary care with viral infections, which can be challenging to diagnose because of their various clinical presentations. Viruses are a large group of submicroscopic infective agents and are separated into two main groups, the DNA and RNA virus types. Viruses can also be classified by their mode of transmission, for example, airborne viruses. This chapter will cover a broad range of viral skin diseases; however, the viral exanthems will be discussed in chapter 6, Pediatrics.

Structurally, viral particles (virion) contain a central core of genetic material (RNA or DNA) within a protein coat (capsid). Some viruses have an outer membrane, known as the envelope, which enables the virus to identify and bind to the host membrane. Viruses require living cells to grow and multiply. Infections occur when the virus introduces its own genetic material into the nucleus of a cell within the host. The host cell will then reproduce normally and will subsequently reproduce the newly introduced viral particles. These particles are then spread throughout the host and infection ensues. Treatment of viral infections depends on the structure of the virus and is aimed at stopping reproduction, not killing the virus, as is often seen in antibacterial therapy.

WARTS

Warts, or verruca, are one of the most common viral infections seen in primary care and affect approximately 7% to 10% of the population. They are small, benign growths caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV), a member of the papovavirus group. They are frustrating for both patients and providers as treatment is often tedious and long term.

Pathophysiology

The papovaviruses are double-stranded, naked (nonenveloped) DNA viruses and are characterized by their slow growth. These viruses typically infect the epithelia of the skin or mucosa, favoring certain locations such as the hands, feet, face, or genitalia. Over100 subtypes of HPV have been identified, and infections can be categorized as anogenital lesions (condyloma acuminatum or genital warts) and nongenital lesions (common warts or verruca). Anogenital warts will be discussed in chapter 21.

While warts themselves are not cancerous, some strains of HPV (usually ones not associated with warts) are oncogenic. Cutaneous warts can be spread through direct person-to-person skin contact or indirectly through contaminated surfaces and objects (e.g., swimming pools, showers). Autoinoculation of the virus from an existing lesion to adjacent skin is commonly seen on the hands in the interdigital and periungual areas. The risk of becoming infected will depend on the immune status of the exposed individual, the amount of virus present during exposure, and the nature of the contact.

Clinical Presentation

Common warts (verruca vulgaris)

Verruca vulgaris, also known as common warts, usually occurs in patients between the ages of 5 and 20 years. Only 15% occur after the age of 35 years. Common warts can be found anywhere on the body but are predominantly found on the hands, particularly the fingers and palms, where fissuring and bleeding can occur at times. A major risk factor is frequent immersion of hands in water; so they are frequently seen in food handlers. Lesions range in size from <1 mm to >1 cm, with the average size being around 5 mm. Typical morphology is a rough, skin-colored papule with a grayish surface that interrupts normal skin lines. The clinical presentation is so characteristic that “verrucous” is used as an adjective to describe the morphologic features of other dermatologic conditions with a similar appearance, such as a seborrheic keratosis.

It is thought that common warts on the body are spread by autoinoculation from the hands. Periungual warts, typically seen at the proximal and lateral nail folds, are often seen in patients who bite their nails (Figure 10-1).Warts may be seen in or around the mouth in these patients as well. Digitate or filiform warts, small (usually 1–3 mm) pedunculated skin-colored papules with multiple, small finger-like projections, can be seen on the face and scalp (Figure 10-2).

Flat warts (verruca plana)

Flat warts, also known as verruca plana, can affect children and young adults, typically present as multiple 2- to 4-mm flat-topped papules. Color can range from slightly erythematous or pink, or tan/brown on lighter skin, to darker brown or hyperpigmented on darker skin. These generally appear in crops on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, elbows, or knees. Men who shave their faces, and women who shave their legs or underarms, can spread the virus and develop numerous flat warts at the site. This is frequently seen in atopic patients from scratching. The distribution is usually more linear (Figure 10-3). Fortunately, of all HPV types, flat warts have the highest rate of spontaneous remission.

Plantar warts (verruca plantaris)

Plantar warts, also known as verruca plantaris, typically present as hyperkeratotic, flesh-colored verrucous papules or plaques. It is common to see multiple lesions present at the same time. Size can range from <1 mm to >1 cm. Lesions may be mistaken for either a callus or a corn, due to their tendency to occur on the pressure points on the ball of the foot, particularly at the mid-metatarsal area. A callus is a circumscribed area of superficial hyperkeratosis, caused by repeated friction or pressure. A corn, or clavus, is a circumscribed thickening of the skin with a central translucent, hornlike core, also caused by repeated friction or pressure. If a callus is pared down, it will reveal normal-appearing skin underneath. If a corn is pared down, it will reveal a clear, horny core. This can be useful in determining diagnosis and treatment.

FIG. 10-1. Periungual warts.

Anogenital warts and condylomata acuminata

Genital warts are the most common sexually transmitted infection. The estimated lifetime risk for infection in sexually active adults can be as high as 80%. Genital HPV is closely linked with cancer of the cervix, glans penis, anus, and vulovovaginal area. There are more than 30 types of HPV associated with genital warts (see chapter 23) and at least 15 types that are oncogenic or high risk.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Warts |

• Seborrheic keratoses

• Acrochordons (skin tags)

• Clavus (corn) or callus

• Molluscum contagiosum (MC)

• Squamous cell carcinoma

FIG. 10-2. Filiform wart.

FIG. 10-3. Flat warts.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is made on clinical appearance. Warts will always interrupt normal skin lines (dermatoglyphics; Figure 10-4), and usually, thrombosed capillaries can be seen (Figure 10-5). If not immediately apparent, a no. 15 blade can be used to lightly pare away hyperkeratotic debris from the surface of the lesion. When this is done, pinpoint black to red dots, which represent the thrombosed capillaries, will be revealed. This is considered a diagnostic sign and is not seen in other skin lesions with a similar clinical appearance.

Although seborrheic keratoses can have a very verrucous appearance, the presence of pseudohorn cysts (keratin deposits within the thickened surface) on close examination can help to differentiate them from warts. Seborrheic keratoses are also often pigmented. Skin tags are soft, fleshy, pedunculated skin-colored papules that can have a clinical appearance similar to filiform wart, but will lack the characteristic finger-like projections on close examination.

FIG. 10-4. Interrupted dermatoglyphics of warts.

FIG. 10-5. Thrombosed capillaries after paring wart. This sign is pathognomonic.

A corn or clavus can commonly be mistaken for a wart because of its tendency to interrupt normal skin lines, but will not have the capillary dots when pared. Squamous cell carcinoma should be considered when lesions have irregular growth, ulceration, or are resistant to therapy, particularly when seen in sun-exposed areas or in immunosuppressed patients. Biopsy is not typically necessary, especially in nongenital lesions, but may be done in challenging cases to confirm the diagnosis.

Management

Warts are a benign skin condition, and spontaneously resolve in up to two thirds of patients, without treatment, within 1 to 2 years. Despite this, warts are a frequent reason for office visits and dermatology referrals. The majority of warts can be successfully treated in the primary care setting or even by the patient at home. The plan of care should be based on the clinical appearance, location, age, and the immune status of the patient. Clinicians should remember that verrucae do not necessarily need to be treated. Monitoring or no treatment is an acceptable option for the patient.

Treatment is indicated if the lesions are painful or interfere with function, and should be pursued before they multiply and while they are still small. Viruses cannot be seen, so even if the treated area appears normal, the virus may exist in the remaining tissues, and the wart may recur. All existing warts should be treated at the same time, if possible.

The goal of therapy is to remove the wart without leaving a scar. Current therapies are not wart specific, and the mechanisms of action in existing therapies are either destructive or immune-based. Therapies available are both over-the-counter and in-office treatment; both may take several weeks or months and recurrence is common. A Cochrane review of evidence-based studies showed that salicylic acid and cryotherapy are the two preferred treatment methods. Table 10-1 summarizes treatment options.

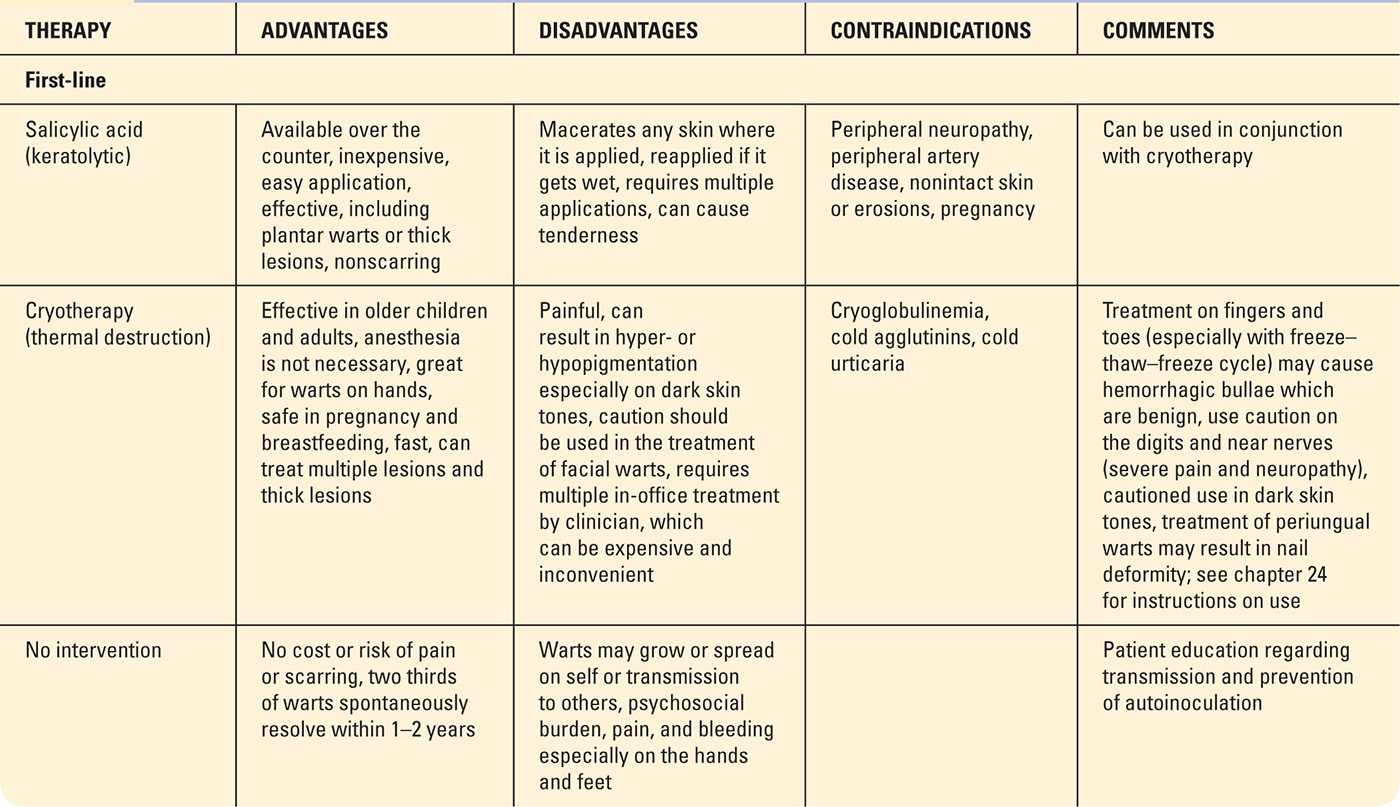

First- and Second-line Treatment Options for Warts |

Destructive therapies

Salicylic acid is generally first-line therapy and is available in liquid form, topical plasters, or patches and can be used by adults and children. It should be avoided in patients with peripheral neuropathy as the extent of tissue damage can go unnoticed and the risk for impaired healing may exist. The liquid forms come in two strengths, 17% (Occlusal HP, Duoplant, Compound W, Duofilm, and Wart-Off) and 27.5% (Virasal). These are used in children and on thinner warts in adults, allowing for easy application to multiple areas. However, lower-strength preparations may not be as effective in the treatment of thick or plantar warts. In these cases, more potent preparations containing 40% salicylic acid in plaster form (Mediplast or Duofilm patch) may be used. If treatment is performed in the office, a no.15 blade should be used by the clinician to pare down the thick keratotic layer prior to treatment in order to allow the medication to effectively penetrate to the infected tissue and hopefully shorten course of treatment.

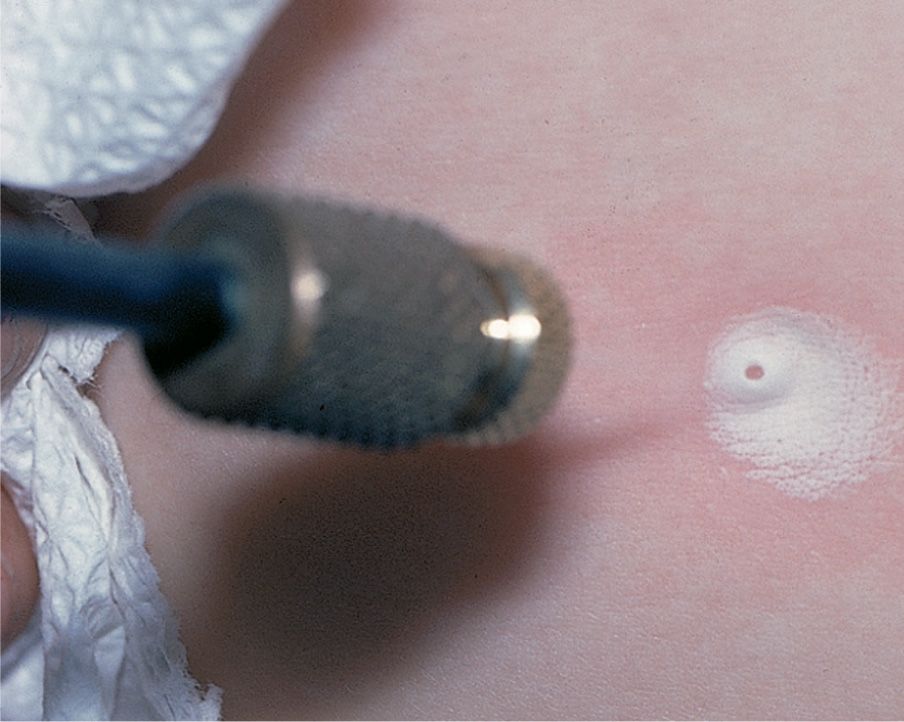

Cryotherapy, using liquid nitrogen, is the most common in-office treatment of warts. This is useful in older children and adults, but poorly tolerated in young children because of the associated discomfort. Multiple treatments spaced about 2 to 4 weeks apart are typically required. Patients should also be instructed to use salicylic acid between treatments after the blister has resolved to aid in resolution.

Duct tape is a commonly used household remedy for warts; however, there is conflicting evidence to support its effectiveness. If desired, the silver brand of duct tape that is sticky enough to adhere to the skin is recommended. The goal is to keep the wart occluded with the duct tape as much of the time as possible and can be used in combination with salicylic acid for enhanced benefit.

Cantharidin liquid 0.7% is a topical destructive agent that is used by many providers in the office setting. Also known as cantharone, cantharidin is an extract of a blistering insect that is an effective treatment approach for children since the application process is pain-free. The patient can, however, develop pain when the treated sites evolve into blisters. Canthacur PS is a combination of cantharidin, podophyllin 5%, and salicylic acid 30%. This is a good choice for patients with multiple, thick plantar warts where deeper penetration is needed. Repeating treatments every 3 to 4 weeks may be required. Cantharidin is not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); however, it is on the FDA’s proposed bulk substances list, which allows preparations containing cantharidin to be administered by providers in the office. See chapter 24 (Skills Section) for details on cantharidin application.

Immune-based therapies

There have been reports of the off-label use of oral cimetidine given in doses of 30 to 40 mg/kg/day being effective in the treatment of warts. This is thought to be due to its systemic immunomodulatory effects. Although this medication is available over the counter, caution should be used when recommending this treatment as there are multiple potential drug interactions associated with its use. The medication by itself is generally safe and well tolerated. Additional immune-based therapies, including topical agents and intralesional treatments, may be available for use by an experienced practitioner in a specialty setting.

Advanced therapies

Sometimes warts can be recalcitrant to common therapies. Advanced treatments or third-line therapies are available, but should be administered by an experienced dermatology provider. Other topical therapies are used effectively but are off label for use in the treatment of warts and include imiquimod cream, 5-fluorouracil, and squaric acid dibutylester. Surgical excision, ablative laser, curettage and desiccation, and snip or shave excision can be performed depending on patient circumstances and office setting. Some dermatology specialists use intralesional immunotherapy with candida antigen or bleomycin. These more aggressive therapies can have significantly higher risks for infection, scarring, and side effects, which should be discussed prior to the procedure with the patient.

Referral and Consultation

Patients with recurrent, recalcitrant, or clinically atypical lesions should be referred to a dermatologist for evaluation and treatment. For patients who do not respond to first- or second-line therapies, consider a referral to a dermatologist for more advanced treatment options.

Special Considerations

Immunosuppression. In general, warts of all types are more common and more difficult to treat in immunosuppressed patients. The clinical presentation may be different, making correct diagnosis of the lesion challenging. A referral to a dermatologist or for biopsy may be necessary.

Pediatrics: Treatment should be aimed at using the least painful methods and lowest potential for permanent side effects like scarring and dyschromia. More destructive methods should be reserved for the most difficult cases where scarring is not a consideration.

Pregnancy: Salicylic acid is a pregnancy category C medication and should not be used in pregnant patients due to the possibility of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus associated with its use. Cryotherapy is the treatment of choice in pregnancy.

Prognosis and Complications

Warts are self-limiting and will spontaneously resolve, most within 2 years. Warts that have been present for an extended period of time are less likely to resolve spontaneously. Emphasis should be placed on the fact that warts may take weeks to months to resolve, so that patients do not become discouraged and stop treating lesions at home prematurely. Also remind patients that recurrence is common and can be frustrating.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Education is particularly important for patients treating lesions at home. It is important to review with the patient that salicylic acid will destroy healthy skin as well as the wart, and that the medication should only be applied to the affected area and a few millimeters of surrounding skin to ensure complete treatment. Plain petrolatum can be applied to the normal skin surrounding the wart prior to treatment in order to prevent damage to normal skin.

Prior to treatment, it is also helpful to soak the area in warm water to help soften the skin and allow for better penetration of the medication. Plasters or patches are affixed to clean skin and kept dry for 2 to 3 days. The patch is then removed, the wart pared down with a nail file or pumice stone, and the process is repeated until the wart has resolved. It is important to instruct patients to follow these steps before reapplying the salicylic acid. It should be noted that whatever tool they are using at home to pare down the warts should be dedicated only for this purpose and should not be used elsewhere on the body, or by other members of the household to minimize autoinoculation or spreading of warts. Instruct the patient to use an electric shaver (not a razor) on warts in hair-bearing areas such as the face or legs. For plantar warts, avoid going barefoot through the house and disinfect the shower base with a diluted bleach solution after bathing. Be sure to wear sandals or shower shoes in public facilities or pools.

Follow-up is individualized and depends on the patient, the extent of the disease, and the treatment being utilized. If a wart is being treated by the practitioner within the office setting, reasonable follow-up is every 2 to 4 weeks.

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

MC is a self-limiting viral skin infection commonly seen in primary care. This challenging skin eruption can have tremendous psychosocial impact that drives patients to seek treatment for the infection. Patients, families, school and daycare facilities, and clinicians can become frustrated with attempts to eradicate MC.

Although MC is a common infection of childhood, it can occur in adolescents and adults. In adults, genital lesions are usually sexually transmitted. Anogenital lesions in children are usually spread through autoinoculation. Patient populations like those with atopic dermatitis or immunosuppression have a higher incidence of MC when compared to the general population.

Pathophysiology

MC is a large double-stranded DNA virus that consists of four closely related members of the poxvirus group. The virus contains unique genes that encode proteins and impairs the host’s immune response and ability to fight the infection. MC is a localized, subacute viral infection of the epithelium that is spread by direct skin-to-skin contact, especially with wet or disrupted skin surfaces. Swimming or bathing with an infected person can increase the risk of transmission. It may also be spread by autoinoculation, sexual contact, shared clothing, and towels. The incubation period can range from 1 to 7 weeks.

Clinical Presentation

MC lesions typically present as 2- to 5-mm firm, skin-colored to pink, pearly dome-shaped papules with a central dell or umbilication (Figure 10-6).The dell may not be obvious but a soft white central core may be present. In children, the distribution may be generalized and can range from a few to more than 100 lesions. Common areas of involvement include the face, trunk, and extremities. Genital lesions can occur in up to 10% of childhood cases with widespread involvement. If the genitals are the only area affected, the possibility of sexual abuse should be considered.

Adults will typically have fewer than 20 MC lesions, commonly seen on the lower abdomen, upper thighs, and the penile shaft in men. Mucosal involvement is very uncommon; however, sexually transmitted lesions will occur in the anogenital region or pubis. In atopic patients, lesions will commonly occur in areas of dermatitis (Figure10-7). Lesions seen in immunocompromised patients may be large, up to 1.5 cm, and known as giant molluscum or may be widespread with hundreds of lesions.

MC can spontaneously resolve in immunocompetent patients within about 2 months, and infection usually clears completely in several months. Lesions can become erythematous and swollen, which many believe is a sign of impending clinical resolution or the beginning of the end (BOTE) (Butala, Siefried, Weissler, 2013). Lesions may be pruritic or sometimes pustular. Molluscum dermatitis, a common phenomenon, is characterized by the development of eczematous patches or plaques surrounding the lesions. The dermatitis has been attributed to the localized reaction to the virus.

FIG. 10-6. Classic molluscum lesion.

FIG. 10-7. Molluscum in atopic dermatitis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Molluscum contagiosum |

• Genital warts

• Folliculitis

• Keratosis pilaris

• Basal cell carcinoma

• Infectious processes such as cryptococcosis or histoplasmosis

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is clinically made by the characteristic appearance of the lesions. MC lacks the verrucous appearance of warts and presents as discrete lesions, whereas warts often coalesce into larger lesions. Solitary lesions or a giant molluscum that occurs on the face can be differentiated from basal cell carcinomas that typically present as a translucent skin-colored papule with telangiectasias and rolled borders.

Biopsy is not necessary but may be performed to confirm the diagnosis especially in the case of large lesions or extensive involvement. The virus itself cannot be cultured; however, bacterial culture may be needed if there is concern for secondary infection. If the central umbilication or dell is not obvious, a dermatoscope or magnifying lens may help identify the central core.

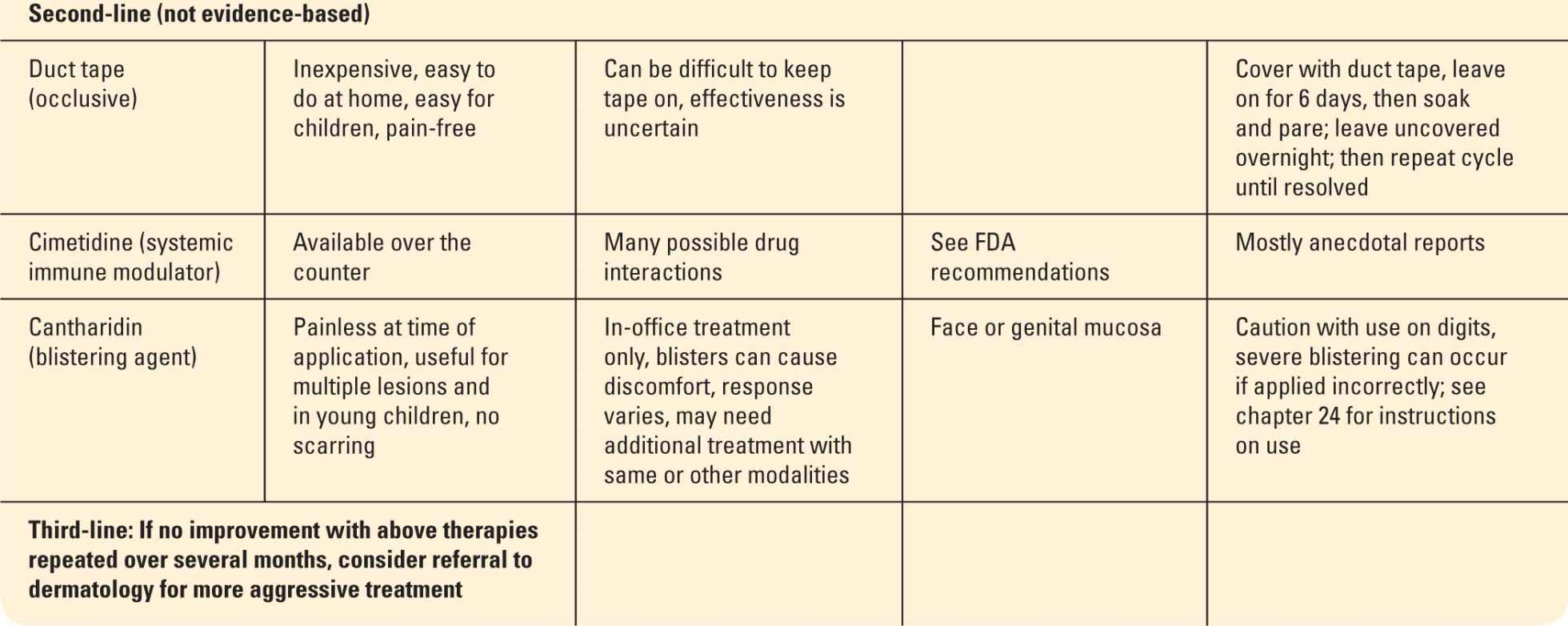

Confirmation can also be made in the office by gently curetting the white, central core from the lesion, placing it between two slides with a drop of potassium hydroxide (KOH). The slide is gently heated and then crushed with firm, twisting pressure. The contents from the central core contain most of the viral cells and can be directly examined with microscopy. Molluscum bodies appear as dark, round cells that disperse easily with slight pressure (Figure 10-8). Normal epithelial cells are flat, varied rectangular shapes, and tend to remain stuck together in sheets.

CLINICAL PEARLS

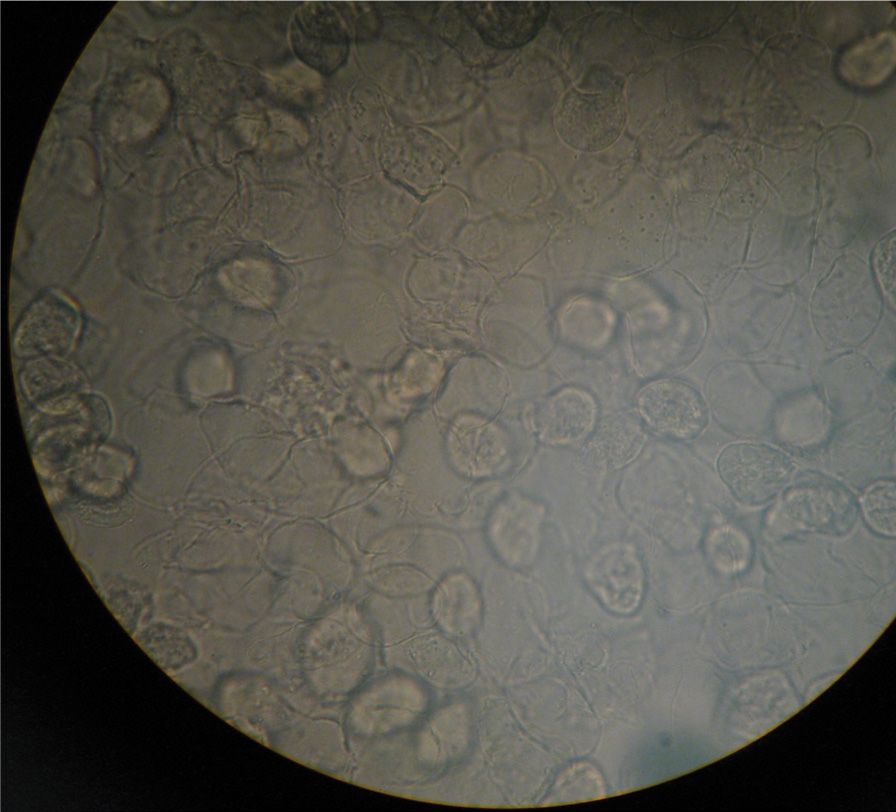

![]() The central umbilication may not always be visible on clinical examination. Lightly spraying or touching the surface of the lesion with liquid nitrogen will often reveal this distinctive finding.

The central umbilication may not always be visible on clinical examination. Lightly spraying or touching the surface of the lesion with liquid nitrogen will often reveal this distinctive finding.

![]() The umbilication will appear against the frozen white background and is a helpful diagnostic sign (Figure 10-9).

The umbilication will appear against the frozen white background and is a helpful diagnostic sign (Figure 10-9).

FIG. 10-8. Molluscum bodies on KOH prep.

Management

MC can ultimately resolve without any treatment. Therefore, the plan of care should be individualized to the patient. Consideration should be given to the patient’s age, location of lesions, number of lesions, risk for scarring, risk for hyper- or hypopigmentation, and immune status. Treatment may be provided in order to prevent lesions from spreading to other areas on the body or transmission to others. All sexually transmitted lesions should be treated along with screening for other sexually transmitted infections. Further treatment indications include pruritus, secondary infection, surrounding dermatitis, or scarring.

Prior to treating MC, a full skin examination should be performed to identify any other lesions on the body. Incomplete treatment can result in autoinoculation and treatment failure. In cases where there is associated dermatitis or pruritus, the provider may consider treating the patient with a topical agent that will help to repair and maintain the epidermal barrier.

There are many additional treatment options available; however, a 2012 Cochrane review concluded that there is no evidence showing that one method is convincingly more effective than the others. Topical treatment is common and includes the use of cantharidin, as discussed previously in the treatment of verruca. Since the application is painless, children are more cooperative, but painful blisters may follow application. Clinicians should consider testing 2 to 3 lesions initially to ensure that the patient does not have sensitivity to it.

FIG. 10-9. Frozen molluscum. The central dell becomes apparent with light cryotherapy.

Cryotherapy is a destructive method that can be used in primary care but has limitations due to the discomfort of the procedure, especially in children. Other therapies are geared toward removing the viral core of the MC. Curettage is a successful method used by experienced clinicians for treatment in children or adults with a limited number of lesions. Topical anesthetic cream (EMLA) can be applied 30 to 60 minutes prior to treatment to minimize the discomfort associated with the procedure. This method may also cause a small scar so the treatment site should be chosen carefully. Nicking the lesion with a no. 11 blade and sterile needle allows the removal of the central core and can be effective. Less invasive approaches include application of surgical or duct tape daily (after bathing) for 16 weeks, which can lead to a cure in up to 90% of children. Strong adhesives may cause a contact dermatitis.

Referral

In recalcitrant cases, generalized widespread lesions, or where immunosuppression is suspected or confirmed, referral to a dermatologist would be recommended. Treatment modalities that may be utilized in a dermatology setting include imiquimod, podophyllotoxin 0.5%, laser therapy, topical retinoids, trichloroacetic acid, and cidovir. Lesions located in the periocular region should be referred to an ophthalmologist for management.

Special Considerations

Immunosuppression: Patients may be referred to an infectious disease specialist for consideration of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. Patients with extensive lesions should be tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the possibility of other immune deficiency disorders should be considered.

Genital lesions: Should raise suspicion for other sexually transmitted infections.

Pregnancy: Curettage, cryotherapy, and incision with expression of the central core are all safe treatment options to use during pregnancy. Podophyllin, podofilox, and imiquimod are all teratogenic and are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Prognosis and Complications

MC is generally self-limiting and is not associated with malignancy. Complications include secondary infection and scarring as a result of treatment. In immunosuppressed patients, MC can be difficult to treat and may recur for years.

Patient Education and Follow-up

While it is not necessary to isolate the infected individuals, patients and parents of infected children should be educated on transmission-reducing methods. Children with MC should not be prevented from attending school or daycare. Lesions in areas that are likely to come in contact with others, such as those on the arms or legs, should be covered with clothing or a watertight bandage. Patient should be instructed to avoid scratching to prevent autoinoculation.

Infected children should not bathe with others, and towels should not be shared in order to prevent spread of infection. Sexual activity with affected individuals should be avoided until lesions are resolved. Condoms will not provide a barrier from areas commonly affected with MC. Patients with atopic dermatitis and a history of molluscum and/or flat warts can benefit from regular moisturizing with a preparation containing ceramides to protect the normal skin barrier and help prevent autoinoculation. The use of topical corticosteroids in these patients is controversial.

Follow-up and monitoring of patients with MC is dependent on the treatment modality used and the number of lesions on individual patients.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is one of the most prevalent infections worldwide. It is estimated that about 90% of adults in the United States have HSV-1 antibodies. HSV infections are caused by two different human herpes virus types. HSV-1 is more prevalent than HSV-2 and is typically associated with oral herpes simplex infections (cold sores). HSV-2 is typically associated with genital herpes simplex infections. However, HSV-1 has been found in genital infections and HSV-2 in oral infections, presumably as a result of oral genital sexual contact, or autoinoculation. Genital HSV infections are discussed in chapter 21.

Pathophysiology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree