REACTIVE CONDITIONS

Intravascular Papillary Endothelial Hyperplasia (Masson Tumor)

Not an uncommon condition, intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia, or Masson tumor, represents an unusual endothelial proliferation in an organizing thrombus that can be misdiagnosed as angiosarcoma (2).

Clinical Summary. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia arises primarily within a venous channel or secondarily within a preceding angioma or some type of vascular anomaly, including hemorrhoids, as in Masson’s original description. Secondary Masson tumor often occurs in deep-seated hemangiomas. An exceptional case of an extravascular location in association with a hematoma has been reported (3). The lesions are almost always solitary, arising in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or even muscle with the head and neck region and the upper extremities. The fingers especially are the most common sites. Exceptional instances of multiple lesions of the lower extremities simulating Kaposi sarcoma (4), simultaneous multiple lesions of skin and bone (5), and multiple lesions associated with interferon beta treatment have also been described (6). All ages can be affected, although there is a slight female predominance (2). Primary lesions are usually tender nodules less than 2 cm in size, whereas secondary lesions occur because some preceding vascular abnormality increases in size.

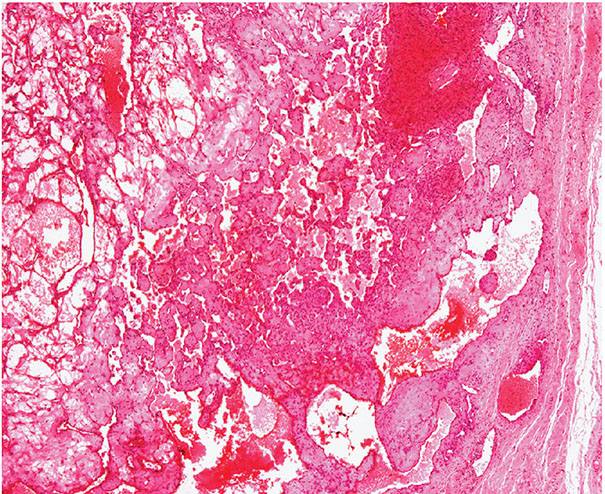

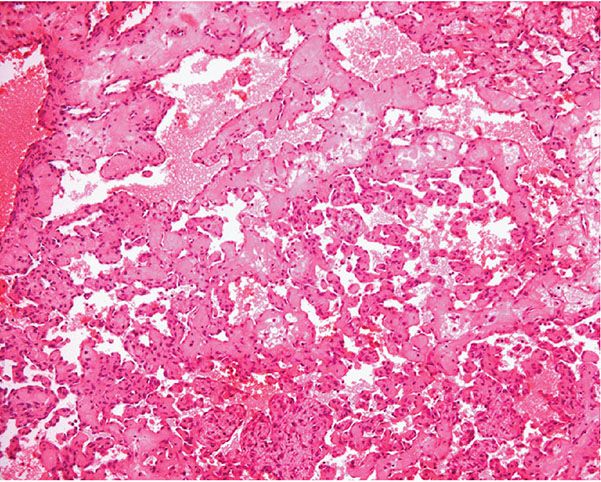

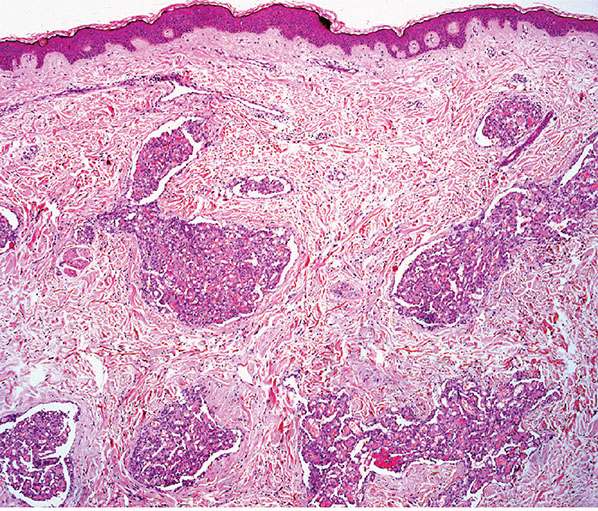

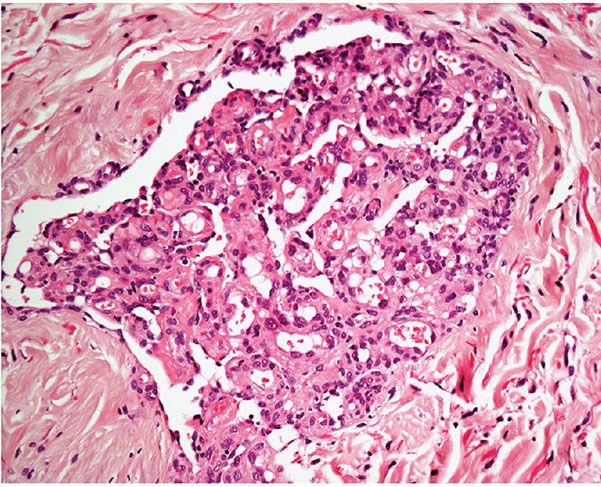

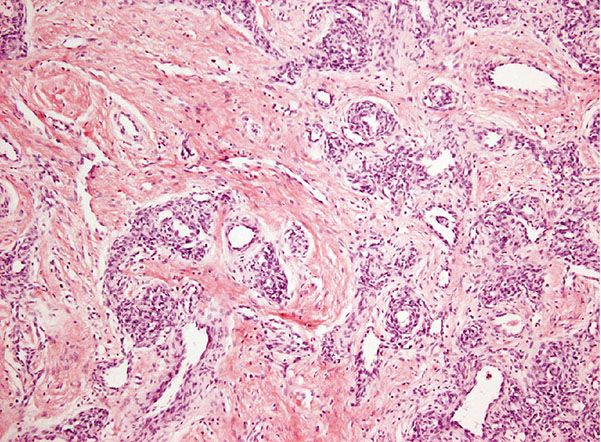

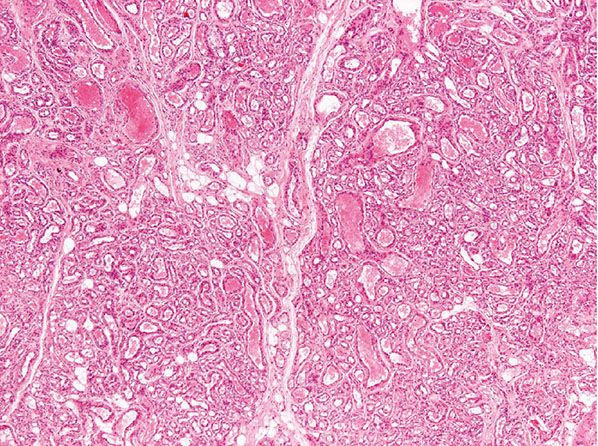

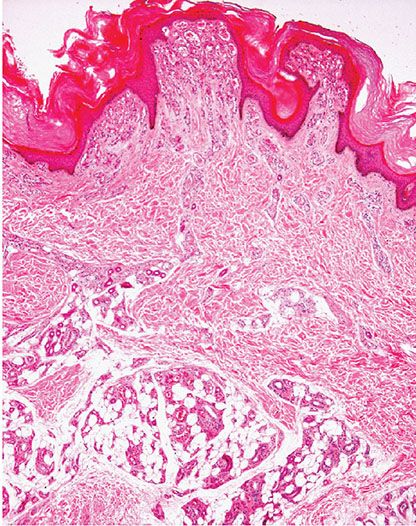

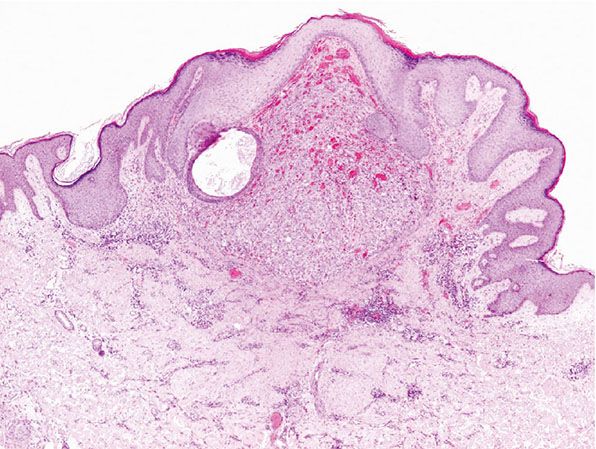

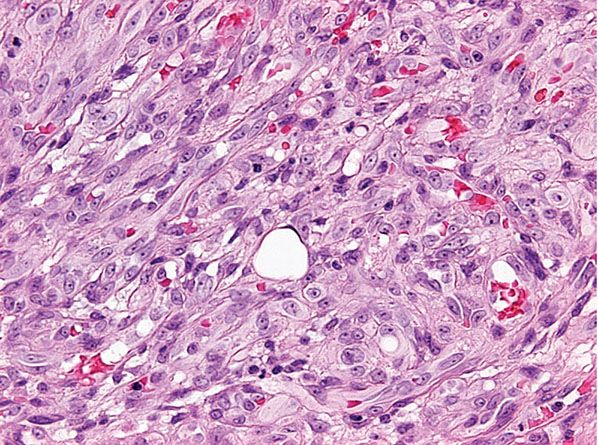

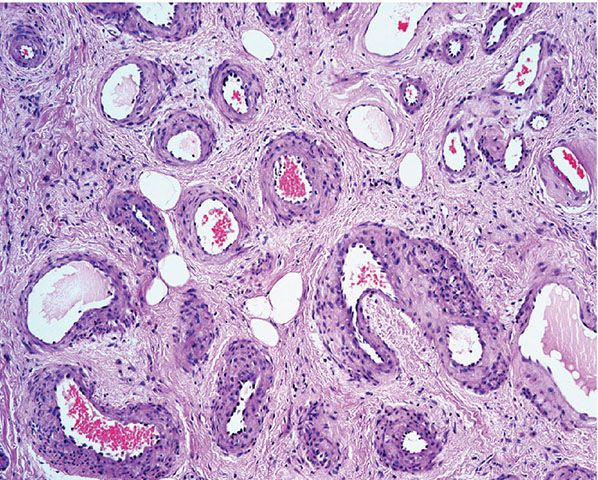

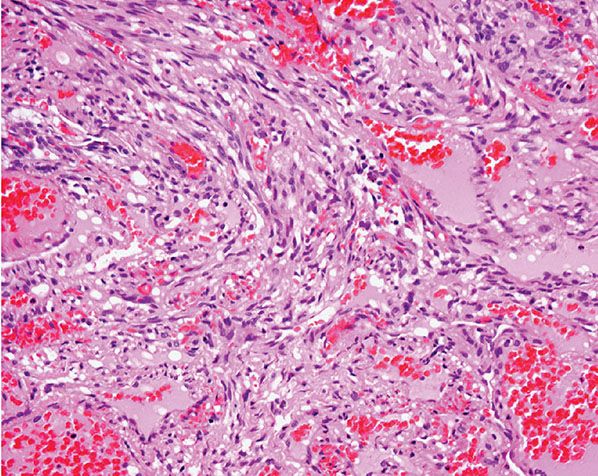

Histopathology. Often, low-power examination allows recognition of the intravascular nature of the process in a single thin-walled vein (Fig. 33-1) or as part of a preceding angiomatous condition. Extravascular lesions fail to reveal a blood vessel wall despite serial sectioning. The main lesion consists of a mass of anastomosing vascular channels with a variable degree of intraluminal papillary projections (Fig. 33-2). The stroma consists of hyalinized eosinophilic material that may merge with uncanalized thrombus remnants. The infiltrating vascular channels show enlarged and prominent endothelial cells that may be “heaped up” to give rise to intraluminal prominences, but atypia and mitotic activity are slight.

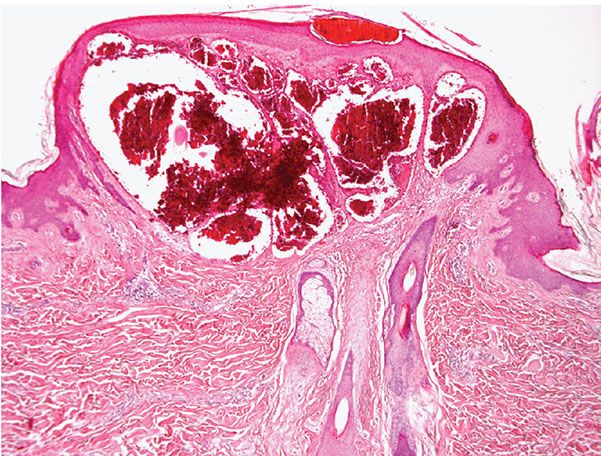

Figure 33-1 Primary intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Part of a markedly dilated vascular channel with prominent papillary structures intermixed with red blood cells and fibrin.

Figure 33-2 Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Typical hyaline papillary projections lined by endothelial cells focally mimicking a dissection of collagen pattern.

Differential Diagnosis. The occurrence of areas of somewhat atypical endothelial-lined channels apparently showing a “dissection of collagen” appearance can closely simulate a well-differentiated angiosarcoma. However, the stroma is not collagen and thus is not refractile on polarization, and the changes are localized and occur within a preceding vessel or a vascular anomaly. Usually, angiosarcoma shows a much greater degree of nuclear atypia, multilayering, and mitotic activity.

Principles of Management. Simple excision.

Angioendotheliomatosis

For many years, two distinctive forms of angioendotheliomatosis were recognized: an aggressive variant with systemic involvement and poor prognosis, and a reactive self-limited form with a benign course usually restricted to the skin. However, the so-called malignant angioendotheliomatosis shows no endothelial differentiation but represents a form of angiotropic lymphoma known as intravascular lymphomatosis (see Chapter 31). However, rare cases of epithelioid angiosarcoma can present with intravascular lesions in the dermis, particularly when the primary lesion arises in the lumen of a large blood vessel.

Reactive Angioendotheliomatosis

Clinical Summary. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis is an uncommon condition that almost exclusively affects the skin and presents in patients of either gender with a wide anatomic distribution and predilection for the limbs. Clinical presentation varies from erythematous or brown macules to papules and/or plaques that can be associated with purpura. A livedo-like pattern is sometimes present. In many cases, an association with systemic disease has been documented including cryoglobulinemia (7,8); paraproteinemia; renal disease; amyloidosis (9); antiphospholipid syndrome (10); rheumatoid arthritis (11); cirrhosis (11); polymyalgia rheumatica (11); sarcoidosis (12); myelodysplastic syndrome (13); and systemic infections, especially tuberculosis and bacterial endocarditis (14). Localized forms of the disease are less frequent and include a variant associated with peripheral vascular atherosclerotic disease described as diffuse dermal angiomatosis (14–16). The latter presentation has also been described in association with iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas (17) and in two female patients with pendulous breasts (18).

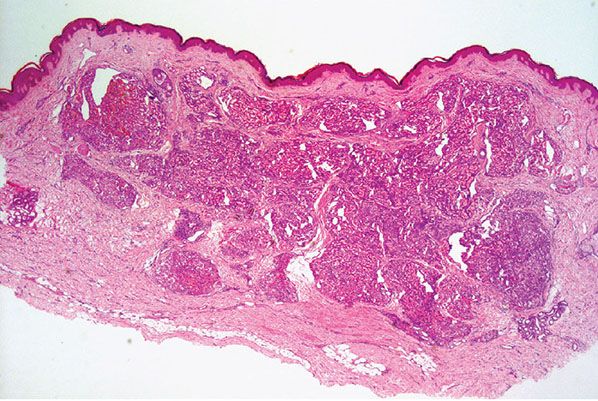

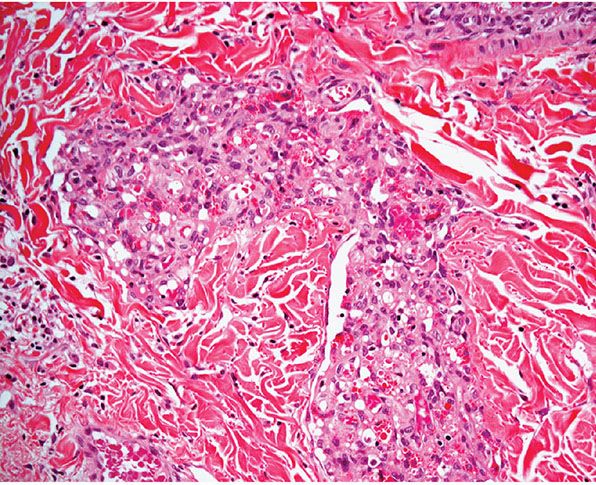

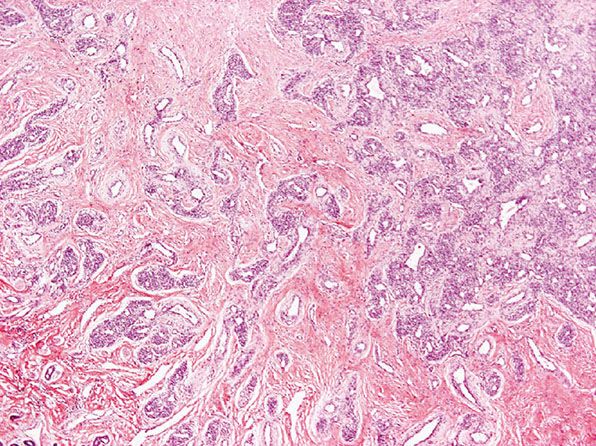

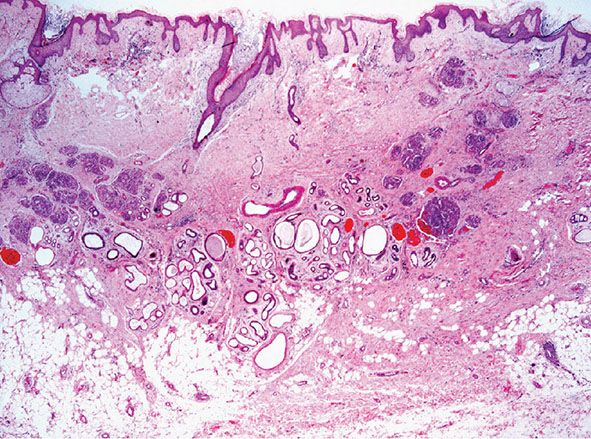

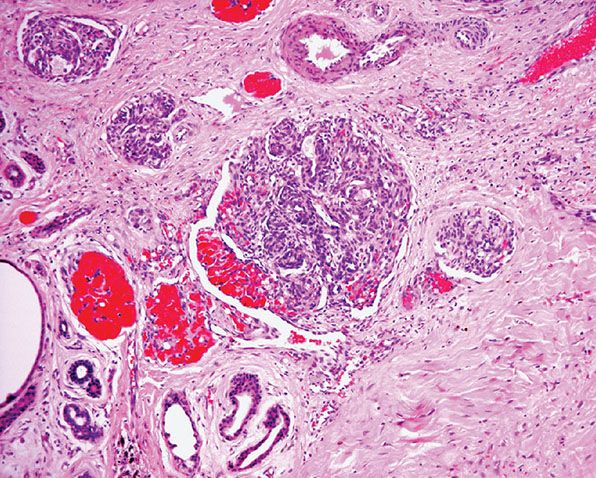

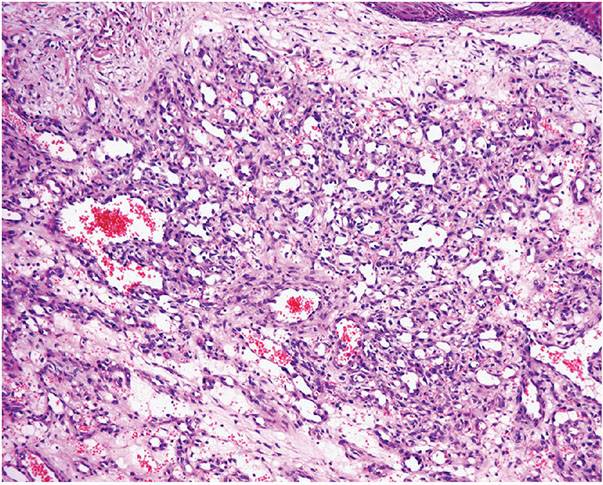

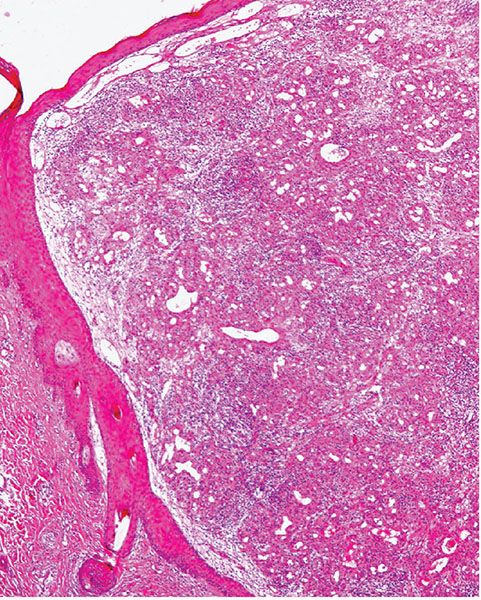

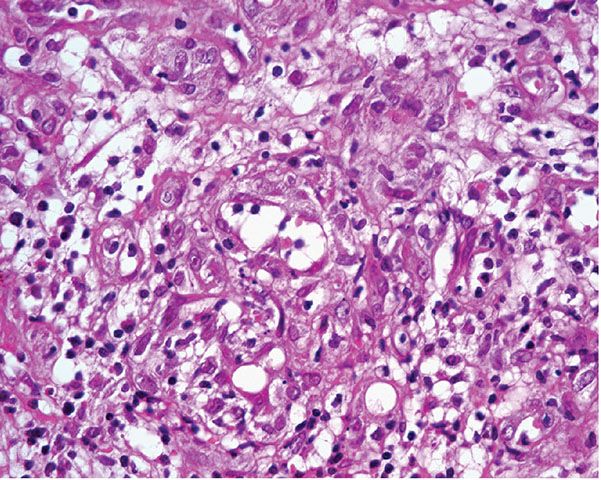

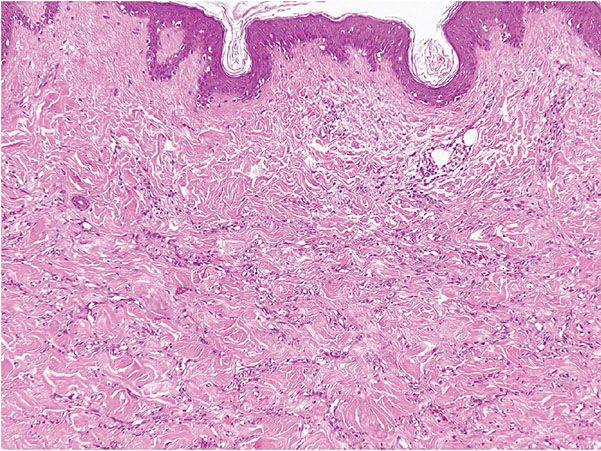

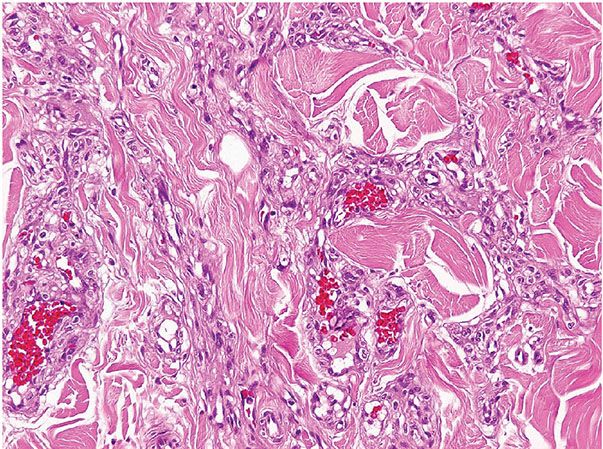

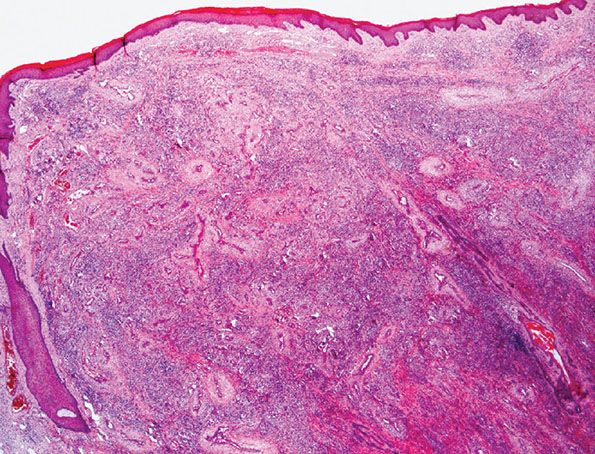

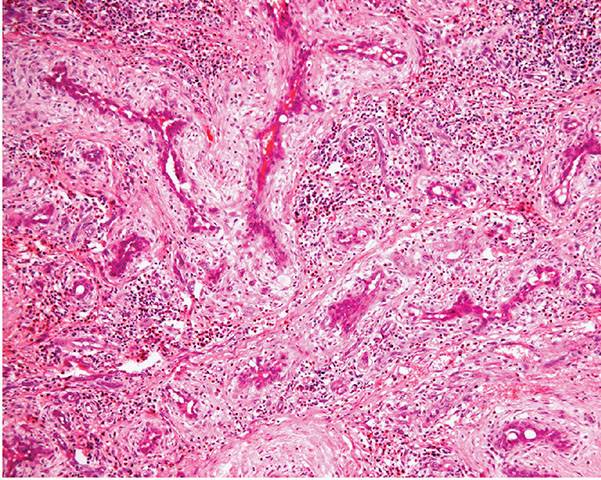

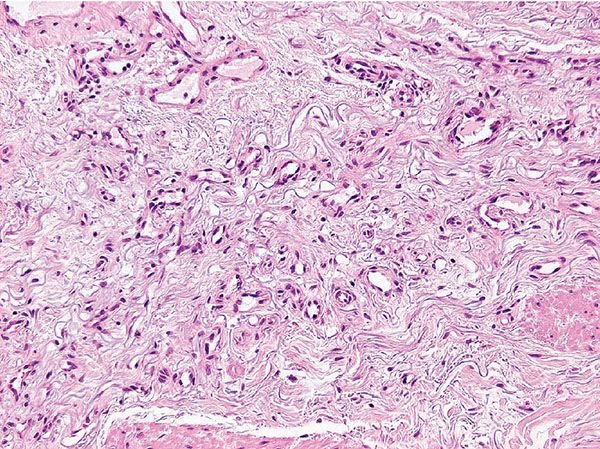

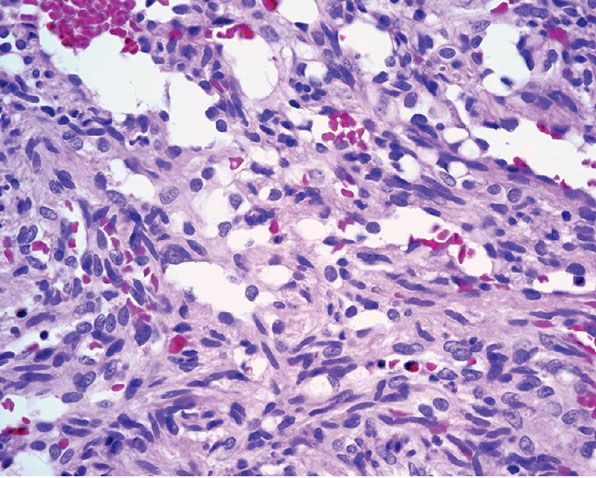

Histopathology. Lesions are predominantly dermal and composed of closely packed, variably dilated vascular spaces (mainly capillaries) (Fig. 33-3) lined by bland but plump endothelial cells surrounded by pericytes. Rare cases display endothelial cells with focal epithelioid change (11). Small lumina might be apparent, some of which are obliterated by endothelial cells or fibrin thrombi. Often, the capillaries appear to proliferate in the lumina of dilated preexisting blood vessels. Hyaline refractile eosinophilic thrombi representing immunoglobulins are present in cases associated with cryoglobulinemia (8) (Fig. 33-4). In diffuse dermal angiomatosis, the proliferating endothelial cells are not present within vascular channels but can be found between dermal collagen fibers.

Figure 33-3 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis. Numerous closely packed capillaries within preexisting dilated blood vessels are seen throughout the dermis.

Figure 33-4 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis. Plump endothelial cells and intraluminal eosinophilic globules in a case associated with cryoglobulinemia.

Histogenesis. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis, in contrast to malignant angioendotheliomatosis, displays universal reactivity for endothelial markers. It has been proposed that the endothelial cell proliferation is induced by a circulating angiogenic factor or, alternatively, especially in cases associated with cryoglobulinemia or atherosclerotic vascular disease, by occlusion of vascular spaces (8). In many instances, the vascular proliferation is triggered by luminal occlusion, and it is likely that thrombosis plays an important role in the pathogenesis (16).

Differential Diagnosis. The histologic distinction from tufted angioma may be difficult, but the clinical presentation of both entities is different, and tufted angioma shows clusters of capillaries in a typical cannonball distribution throughout the dermis with crescent-like dilated spaces that probably are lymphatic in nature in the periphery of many of the vascular tufts. In intravascular lymphomatosis, thin-walled vascular channels throughout the dermis and subcutis appear distended by atypical lymphoid cells, mainly but not always with a B-cell phenotype. Intravascular histiocytosis was originally regarded as the part of the spectrum of angioendotheliomatosis (19). It is however now considered a distinctive entity, with lesions most commonly developing close to involved joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Similar features may also be seen as an incidental finding in biopsies performed for other pathologies, including samples from patients with chronic lymphedema. Histologically, collections of histiocytes are present within the lumina of thin-walled blood vessels. These cells are positive for CD68 and CD163 and may be positive for CD31.

Principles of Management. The condition is usually self-limited or improves when the underlying disease is treated.

Glomeruloid Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Glomeruloid hemangioma is a highly distinctive, rare, reactive vascular proliferation that presents in patients with POEMS syndrome (Polyneuropathy, Organomegaly, Endocrinopathy, M-protein, and Skin changes), usually but not always in association with multicentric Castleman disease (20–24). The skin changes in POEMS syndrome include hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation, hyperhidrosis, sclerodermoid features, and multiple small, vascular papules on the trunk and limbs. Single or multiple lesions with similar morphology have been described in patients with no evidence of POEMS syndrome (25,26). Some single lesions described as such may be examples of the recently described papillary hemangioma (see Papillary Hemangioma section). Hemangiomas with features of capillary hemangioma and glomeruloid hemangioma have been described in an intracranial location in a patient with POEMS syndrome (27).

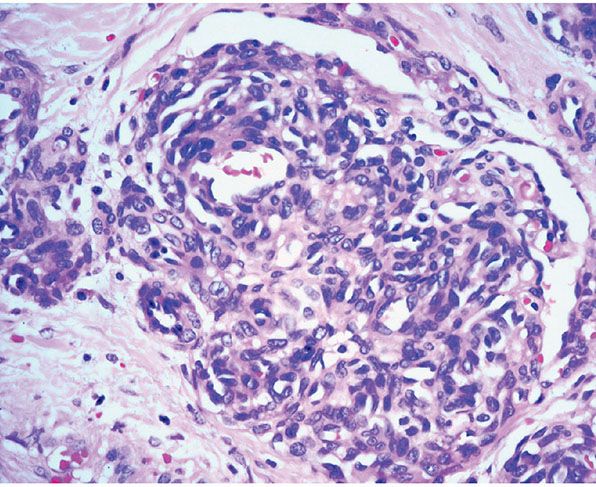

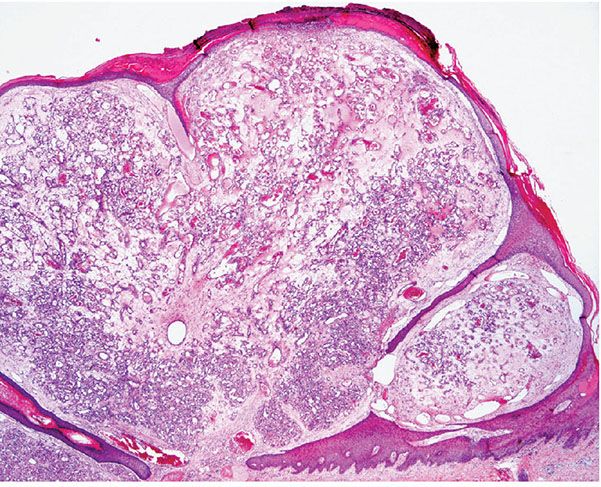

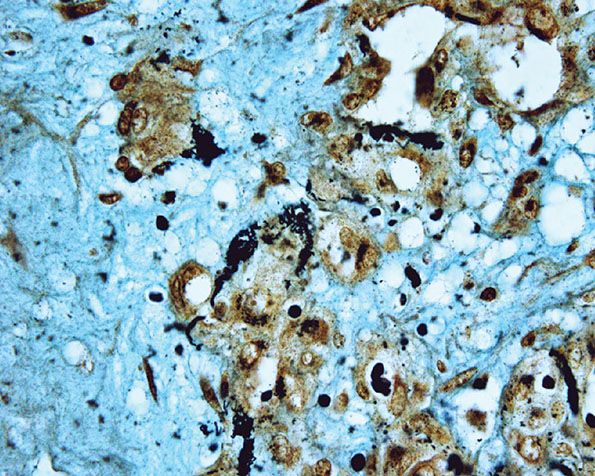

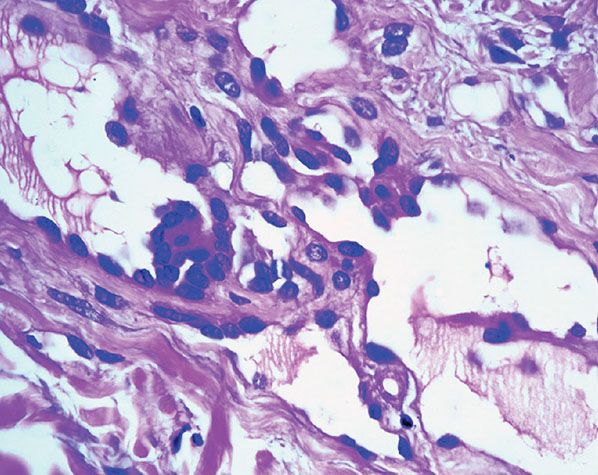

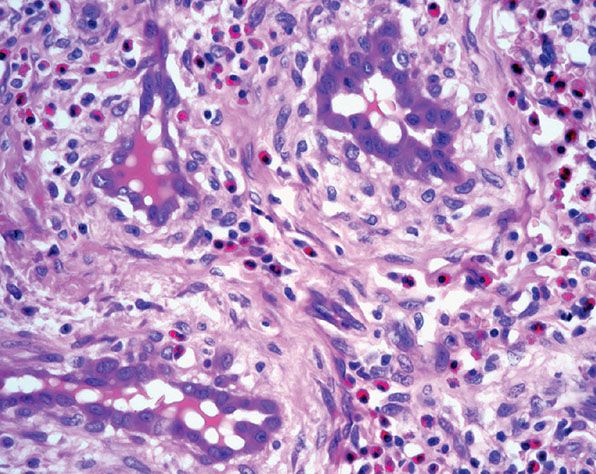

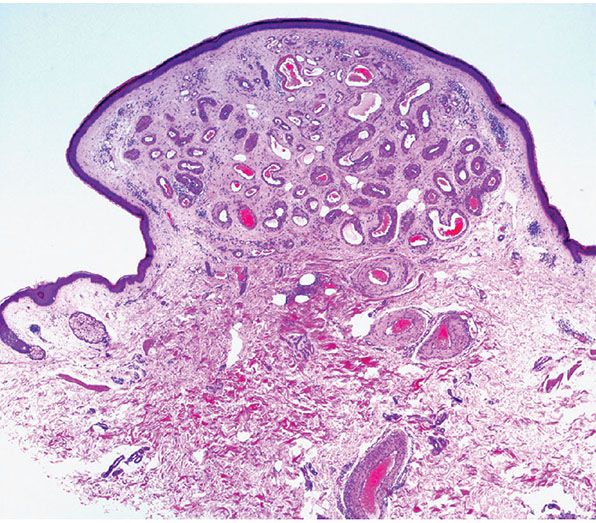

Histopathology. Most vascular lesions in POEMS syndrome show the features of cherry angiomas, and only a small number of lesions have the appearance of a glomeruloid hemangioma. Other lesions may display histologic features that do not fit exactly into a definitive diagnostic category. In glomeruloid hemangioma, there are numerous ectatic vascular spaces throughout the dermis that contain in their lumina clusters of small, congested capillaries surrounded by pericytes bearing a striking resemblance to renal glomeruli (Figs. 33-5 and 33-6). Although the endothelial cells are flat, a few scattered cells appear vacuolated and can show periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive hyaline globules. Initially it was suggested that the latter correspond to deposition of immunoglobulins. More recently however, it has been shown that the inclusions represent giant lysosomes with cellular debris and fat vacuoles known as thanatosomes (28). Staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is negative.

Figure 33-5 Glomeruloid hemangioma. Widely dilated preexisting vascular channels filled with smaller blood vessels. Note the low-power resemblance to reactive angioendotheliomatosis.

Figure 33-6 Glomeruloid hemangioma. Striking resemblance to a renal glomerulus.

Histogenesis. Glomeruloid hemangioma probably represents a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis. The cause of the vascular proliferation in POEMS syndrome has not been established, but it may be induced by an angiogenic factor, possibly the abnormal immunoglobulin in the vascular spaces.

Papillary Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Papillary hemangioma is a recently described variant of hemangioma with striking predilection for the head and neck of adults with male predominance (29). It presents as a long-standing asymptomatic papule, and local recurrence is exceptional.

Histopathology. Dilated, thin-walled vascular channels occupy the dermis and are characterized by the presence of multiple papillary projections with endothelial cells and pericytes associated with a thick basement membrane–like material. The endothelial cells are bland and contain abundant intracytoplasmic eosinophilic globules.

Histogenesis. The etiology is not known but it has been suggested that this hemangioma represents a solitary variant of glomeruloid hemangioma. The latter, however, has a distinctive glomeruloid architecture and lacks papillary projections containing basement membrane–like material and pericytes (30).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

VASCULAR ECTASIAS

Nevus Flammeus

Clinical Summary. The term nevus flammeus is often used to refer to two different lesions: the salmon patch and the port-wine stain. Although both lesions are congenital, the former tends to involute in the first years of life and usually has no association with other types of anomalies, while the latter tends to be persistent and is often related to other malformations. The salmon patch is present in up to 50% of newborns of either gender as an ill-defined, red to pale pink macule, mainly in the nape of the neck, the glabella, or the eyelids (31,32). It was recently reported to be present in 91.2% of hospitalized neonates (33). The port-wine stain occurs in about 0.3% of newborns as a macular, usually unilateral, red-pink lesion, with a predilection for the face (32). Later in life, the lesion becomes darker and raised. Acquired port-wine stains have rarely been described (Fegelers syndrome) in association with trauma, drugs, and even herpes zoster (34,35). Other vascular proliferations including lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) and exceptionally tufted angioma may present within a port-wine stain (36). Familial cases sometimes occur, and the gene has been mapped to chromosome 5q (37,38).

Sturge–Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) is characterized by the presence of a facial port-wine stain, often in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve associated with an ipsilateral leptomeningeal venous malformation, atrophy and calcification of the underlying cerebral cortex, epilepsy, mental retardation, ocular vascular malformations, glaucoma, and contralateral hemiparesis. There is a higher risk of neuro-ocular symptoms when there is involvement of the dermatome V1 by the port-wine stain.

In Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (osteohypertrophic nevus flammeus), hypertrophy of the soft tissues and bones of one or several extremities affected with a nevus flammeus is observed. Associated with this are varicosities or arteriovenous fistulas or both and, less commonly, spindle cell hemangioendotheliomas. Cases presenting with arteriovenous fistulas are sometimes known as Parkes–Weber syndrome. Complications of note are cutaneous ulcers and high-output cardiac failure.

In phakomatosis pigmentovascularis, there is a port-wine stain associated with melanocytic lesions including dermal melanocytosis and nevus spilus (39). Sturge–Weber and Klippel–Trenaunay can also be associated with this condition.

A new clinical syndrome has recently been reported as CLAPO: capillary malformation of the lower lip, lymphatic malformation of the face and neck, asymmetry, and partial/generalized overgrowth (40).

Histopathology. In the salmon patch, dilated capillaries are seen in the papillary dermis. In the port-wine stain, no telangiectases are apparent histologically until the patient has reached about 10 years of age (41). The capillary ectasias thereafter gradually increase with age. Ultimately, when the lesion is raised or nodular, dilation appears not only in the superficial capillaries but also in some of the blood vessels in the deeper layers of the dermis and in the subcutaneous layer. Many ectatic vessels are filled with red blood cells. Lesions with a deep component can be associated with a cavernous hemangioma or an arteriovenous malformation (41).

Histogenesis. Because no histologic abnormalities are present early in life with a port-wine stain, it appears likely that this malformation is the result of a congenital weakness of the capillary walls (41). Thus, the port-wine stain represents a progressive telangiectasia. Antibodies directed against components of the blood vessel wall, collagenous basement membrane protein (type IV collagen), fibronectin, and factor VIII–related antigen have an equivalent distribution and intensity in normal skin and nevus flammeus. Although this does not rule out a structural abnormality of these components, it has been suggested that the alteration may be related to the supporting dermal elements rather than to an intrinsic abnormality in the vessel wall (42). An abnormality in neuromodulation has been proposed as an alternate theory (43).

Principles of Management. Salmon patches tend to regress spontaneously, and laser is the treatment of choice for port-wine stains.

Angiokeratoma

Clinical Summary. Four types of angiokeratoma have been described that represent true ectasias of blood vessels of the superficial dermis (44):

1. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Patients present with numerous clusters of tiny, red papules in a symmetrical distribution, usually in the “bathing-trunk” area. Although often considered synonymous with Fabry disease, which is an X-linked genetic disorder associated with deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme A-galactosidase, identical clinical appearances have been described in patients with other enzymatic deficiencies, including B-galactosidase, neuraminidase, L-fucosidase, and B-mannosidase (45–47). In exceptional cases, presentation is not associated with detectable biochemical abnormalities, and these cases may be familial (48,49).

2. Angiokeratoma of Mibelli. Several dark red papules with a slightly verrucous surface are seen on the dorsa of the fingers and toes. Usually, the lesions appear during childhood or adolescence and measure 3 to 5 mm in diameter (50).

3. Angiokeratoma of Fordyce. Multiple vascular papules of 2 to 4 mm in diameter are seen on the scrotum (51). Similar lesions have been described on the vulva (52). They arise in middle or later life. Early lesions are red, soft, and compressible; later, they become blue, keratotic, and noncompressible.

4. Solitary or multiple angiokeratomas. Usually one and occasionally several papular lesions arise in young adults, most commonly on the lower extremities. They may be congenital, and when located in a restricted area of the lower limbs, the term angiokeratoma circumscriptum is used (53). The lesions range from 2 to 10 mm in diameter. Early lesions appear bright red and soft, but they later become blue to black, firm, and hyperkeratotic (44). Thrombosed lesions are not uncommonly misdiagnosed clinically as malignant melanomas.

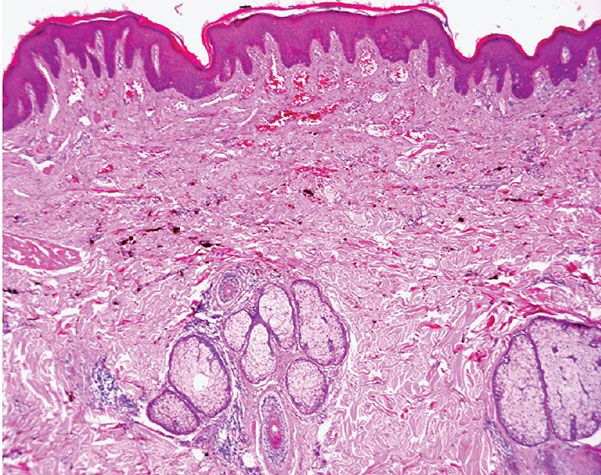

Histopathology. The histologic findings are essentially the same in all four above-mentioned types of angiokeratoma and consist of numerous, dilated, thin-walled, congested capillaries mainly in the papillary dermis underlying an epidermis that shows variable degrees of acanthosis with elongation of the rete ridges and hyperkeratosis (44) (Fig. 33-7). In cutaneous lesions of Fabry disease, cytoplasmic vacuoles representing lipids can sometimes be detected in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and pericytes.

Figure 33-7 Angiokeratoma. Note the ectatic blood vessels in the papillary dermis with overlying epidermal hyperplasia.

Principles of Management. In cases of solitary lesions, simple excision is the treatment of choice. In patients with A-galactosidase deficiency, treatment with the enzyme may result in regression of the lesions (54).

Generalized Essential Telangiectasia

Clinical Summary. Widespread linear telangiectases, mainly on the extremities and sometimes the trunk, may gradually develop in adults, predominantly in women between the third and fourth decades of life (55,56). There is no associated bleeding. Occasional cases are associated with lesions in the conjunctiva and oral mucosa, and exceptionally watermelon stomach has been reported (57).

Histopathology. Dilated, often congested, vessels are seen in the papillary dermis. The walls of the vessels are composed only of endothelium. The absence of alkaline phosphatase activity suggests that it is the venous portion of the capillary loop that participates in the disease process (55,56).

Principles of Management. Laser therapy may result in cosmetic improvement.

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Clinical Summary. This condition is very rare and presents in adults as asymptomatic, progressive, generalized telangiectasia with no involvement of the oral cavity or nails (58). The clinical appearances are indistinguishable from those seen in essential generalized telangiectasia.

Histopathology. Superficial, small dermal vessels appear dilated, and their walls are thickened by amorphous hyaline material. Rarely small blood vessels in the reticular dermis are involved (59). This material is positive for PAS and also for colloidal iron. It represents collagen, as demonstrated by electron microscopy; by immunohistochemistry, it is positive for collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin. Ultrastructure examination demonstrates that the vessels involved are postcapillary venules.

Principles of Management. Success with pulsed-dye laser has been reported (60).

Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia

Clinical Summary. Although unilateral nevoid telangiectasia may be congenital, in most instances, its onset is related to high estrogen levels associated with pregnancy, puberty, and chronic hepatic disease associated with alcoholism and rarely with hepatitis C (61,62). Neurologic abnormalities may rarely be found (63). It is more common in women, and presentation in children is very rare. The telangiectases, which are largely punctate and stellate rather than linear, follow a dermatomal distribution, particularly those associated with the trigeminal nerve and cranial nerves III and IV. Exceptional cases are associated with gastric involvement (64).

Histopathology. Numerous dilated vessels are seen in the upper and middle dermis and, to a lesser extent, in the deeper part of the dermis.

Histogenesis. It has been proposed that the changes seen in this condition are induced by an increase in estrogen receptors in a dermatomal distribution (65). However, this has not been confirmed by immunohistochemistry.

Principles of Management. Some response can be achieved by the use of pulsed-dye laser.

Angioma Serpiginosum

Clinical Summary. Angioma serpiginosum is a rare acquired vascular lesion that usually presents in the first two decades of life with a predilection for females. Anatomic distribution is wide, but lesions often present on the lower extremities. The disorder is asymptomatic, and slow progression occurs over the years. Focal spontaneous regression rarely occurs. Most cases are sporadic, but inherited cases have been reported (66). A typical lesion is characterized by deep red nonpalpable puncta that are grouped closely together in a macular or netlike pattern. Irregular extension at the periphery of the macules may cause them to have serpiginous borders. The deep red puncta represent dilated capillaries.

Histopathology. Dilated, thin-walled capillaries are seen in some of the dermal papillae and the superficial reticular dermis. Epidermal changes and extravasation of red blood cells do not occur.

Histogenesis. On electron microscopic examination, it is apparent that the thickening of the capillary walls is caused by a heavy precipitate of basement membrane–like material mixed with thin collagen fibers and an increased number of concentrically arranged pericytes (67). In addition, some of the dilated capillaries show slitlike protrusions of their lumina and endothelial lining into the surrounding thickened vessel walls. These findings indicate that angioma serpiginosum is not just a simple telangiectasia but represents a vascular malformation (67). It has been reported that the condition is associated with mutations of the gene PORCN on chromosome Xp11.3-Xq12 (68). This theory, however, has been disputed (69).

Principles of Management. Lesions may be treated with pulsed-dye laser.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Osler–Weber–Rendu Disease)

Clinical Summary. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), or Osler–Weber–Rendu disease, is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Up to four variants of the disease have been described, reflecting genetic heterogeneity (see Histogenesis). Although epistaxis may already begin in childhood, the characteristic telangiectases on the mucous membranes do not begin to appear until adolescence, and the cutaneous lesions often appear much later in life, particularly involving the upper part of the body. Typical lesions are small, bright red, nonpulsating papules.

Concomitant involvement of other organs including the gastrointestinal tract, liver, brain, lungs, spleen, kidneys, and adrenal glands is common. Associated vascular malformations are often a feature (70). Morbidity and mortality are mainly related to bleeding from internal organs.

Histopathology. Irregularly dilated capillaries and venules lined by flat endothelial cells are seen in the papillary and subpapillary dermis.

Histogenesis. On electron microscopy, the dilated vessels in the skin and oral mucosa are seen to be small postcapillary venules that normally do not possess pericytes. A defect in the perivascular supportive tissue has been found to be responsible for the breakdown of the junctions between endothelial cells and the resultant hemorrhage (70). A number of genetic abnormalities have been described in the disease. In type 1, HHT is associated with mutations on the endoglin gene on chromosome 9q34.1 (71). In type 2 HHT, the mutation is located on the activin receptor–like kinase gene on chromosome 12q13 (72). In other variants of the disease, mutations have been described on chromosome 5 (73) and on gene MADH4 located on chromosome 18q21.1 (74). In the latter setting, patients also have juvenile polyposis.

Principles of Management. Management of this systemic condition is complex and involves treatment of acute hemorrhagic complications, as well as screening for significant vascular malformations in visceral organs and preventive treatment (e.g., excision, radiation therapy) if appropriate. Specialized centers exist to provide expert advice and management.

Nevus Araneus (Spider Nevus)

Clinical Summary. Nevus araneus, or spider nevus, considered the most common form of telangiectasia, presents at any age, especially in children, with a predilection for the face and upper limbs (75). It is characterized by a central, slightly elevated, red punctum from which blood vessels radiate. Occasionally, pulsation can be observed. Although spider nevi often arise spontaneously, pregnancy, the use of oral contraceptives, and liver disease are factors predisposing to their appearance (75). Spontaneous regression is common as children grow older and after pregnancy.

Histopathology. In the center of the lesion is an ascending artery that branches and communicates with multiple dilated capillaries.

Principles of Management. Lesions can be treated by electrodesiccation or laser.

Venous Lake

Clinical Summary. Venous lake is a small, dark blue, slightly raised, soft lesion occurring on the exposed skin of elderly persons. It can usually be emptied of most of its blood by using sustained pressure. Usually, several lesions are present. The face, ears, and lips are the most common sites.

Histopathology. Venous lake represents a telangiectasia. In the upper dermis, close to the epidermis, the lesions show either one greatly dilated space or several interconnected dilated spaces filled with erythrocytes and lined by a single layer of flattened endothelial cells and a thin wall of fibrous tissue (76). In some instances, in place of fibrous tissue, there is a thin, irregular, noncontinuous, smooth muscle layer (77).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

BENIGN TUMORS

Congenital Hemangiomas

The term congenital hemangioma was first proposed in 1996 to describe a group of hemangiomas that first appear in utero and are fully developed at birth (78). These lesions were probably classified in the past as infantile hemangiomas (IHs) (79), vascular malformations, and even cavernous hemangiomas. These congenital hemangiomas have been divided into rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICH) and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (NICH). Although they seem to represent distinctive clinicopathologic entities, there is some degree of overlap not only between RICH and NICH but also between RICH and IH (80). This means that accurate diagnosis usually relies on close clinicopathologic correlation. It is still controversial whether these lesions are pathogenetically interconnected (80). Interestingly, RICH and NICH express levels of insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA at levels that are very similar to those expressed by IHs in children older than 4 years (81). VEGF receptor-1, however, is expressed at increasing levels in both RICH and NICH compared to IH.

Rapidly Involuting Congenital Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. RICH develops fully before birth and tends to regress during the first year of life. The tumor affects males and females equally and has a wide anatomical distribution with some predilection for the head and limbs (82,83). Some patients with RICH present with thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy early in the neonatal period (84). These alterations are mild and patients do not progress to true Kasabach–Merritt syndrome.

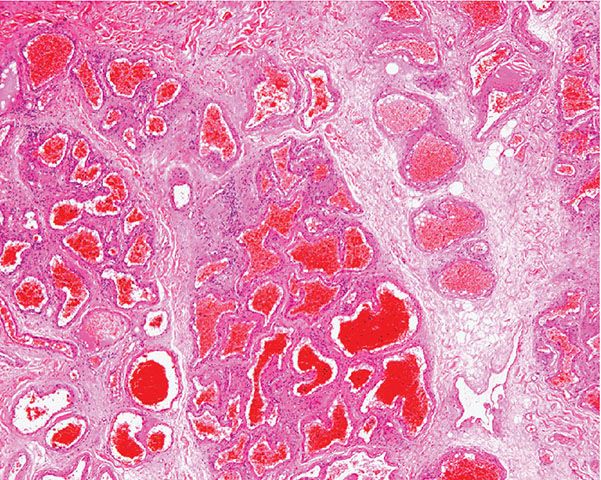

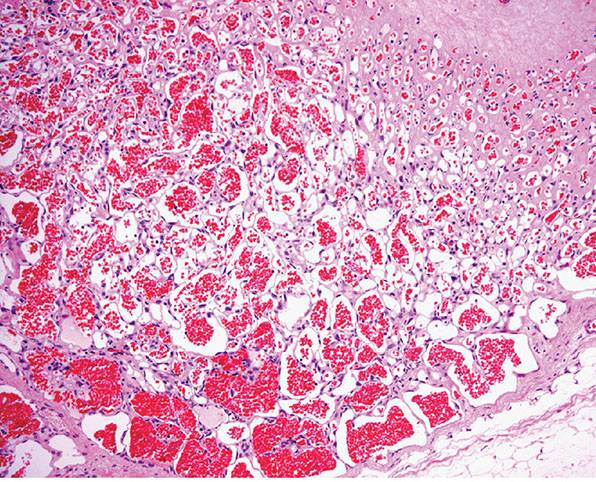

Histopathology. Lesions are mainly subcutaneous and extend focally into the dermis. The architecture is lobular, and between tumor lobules, there are often bands of fibrosis (Figs. 33-8 and 33-9) with focal inflammation, dystrophic calcification, and hemosiderin deposition. Lobules are composed of variably congested capillaries, each of which is surrounded by a layer of pericytes. The overlying epidermis and adnexal structures usually appear atrophic. Larger vascular channels may be found in the fibrotic areas. Individual lobules may show variable fibrosis. Extramedullary hemopoiesis may be seen, and perineural extension is absent. GLUT-1 staining is usually negative in tumor lobules. However, in rare cases, focal positivity may be present.

Figure 33-8 Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma. Fibrous tissue is seen not only within individual tumor lobules but also between different tumor lobules. (Courtesy of H. Kozakevich, MD, Boston, MA.)

Figure 33-9 Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma. Individual lobules are identical on high power to those seen in infantile hemangioma, but there is fibrosis with the lobules. (Courtesy of H. Kozakevich, MD, Boston, MA.)

Differential Diagnosis. This is discussed below, under NICH.

Principles of Management. Tumors usually regress spontaneously. In large lesions or those that affect vital organs, various treatment modalities have been attempted including embolization, surgical excision, and systemic steroids. Propanolol is usually not effective.

Noninvoluting Congenital Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. NICH is fully developed at birth but shows no signs of regression, and it progresses over time (85). There is an equal sex incidence, and although anatomical distribution is wide, there is predilection for the head and limbs.

Histopathology. Vascular lobules tend to be large and are often composed of capillaries and larger, sometimes thicker blood vessels (Fig. 33-10). Draining larger blood vessels are present in tumor lobules. Surrounding the latter, there are areas of fibrosis containing large blood vessels with features of veins and arteries. Arteriovenous fistulas are also identified, and this closely mimics arteriovenous malformations. Histologic distinction can be very difficult, and close clinicopathologic correlation is often necessary. As opposed to vascular malformations, NICH does not tend to recur. GLUT-1 staining is usually negative.

Figure 33-10 Noninvoluting congenital hemangioma. Tumor lobules vary more in size and contain a number of larger vascular channels.

Differential Diagnosis. The main differential diagnosis of RICH and NICH is IH. The latter typically develops shortly after birth, grows rapidly during the first year of life, and tends to involute over a period of several years. The lobules of RICH and IH are often identical, and it has been proposed that distinction between both is mainly based in the presence of bands of fibrosis around tumor lobules, presence of atrophy of adnexal structures and epidermis, and lack of GLUT-1 positivity in the former. In practice, however, and especially in small biopsies, distinction may be very difficult and clinicopathologic correlation is paramount. Staining for GLUT-1, the human erythrocyte glucose transporter, is particularly helpful, as IH tends to be diffusely positive for this marker (86) while RICH is usually negative, and if positive, the positivity, tends to be focal. Distinction between IH and NICH is easier, as the latter tends to display more variability in the size of vascular channels, GLUT-1 staining is usually negative, and arteriovenous fistulas are identified. The main problem with diagnosis of NICH, RICH, and IH is that there is some degree of overlap between the three entities, as demonstrated by the fact that IH may coexist with either RICH or NICH. The problem is further compounded by the fact that some cases of RICH fail to involute completely and behave more like NICH. In such cases, the histologic appearances overlap with those of RICH and NICH. At present, the pathogenetic relation between these groups of lesions remains obscure. Distinction between NICH and vascular malformations may be difficult. Radiologic studies are often helpful, and NICH, RICH, and IH are positive for WT1, while vascular malformations, particularly those that are arteriovenous in nature, tend to be negative for this marker (87).

Principles of Management. Lesions do not usually respond to medical treatment. Surgery is the treatment of choice but may be difficult in large tumors. Embolization may be used in large tumors involving vital structures.

Capillary Hemangioma Variants

Infantile Hemangioma (Strawberry Nevus, Juvenile Hemangioendothelioma, Juvenile Hemangioma)

Clinical Summary. Infantile capillary hemangioma, mostly represented by strawberry nevus, constitutes the most common vascular tumor of infancy, affecting as many as 1 in every 100 live births. Overall, it comprises between 32% and 42% of all vascular tumors (88,89). Lesions usually first appear between the third and fifth week of life, increase in size for several months to 1 year, and then start to regress. A typical lesion consists of one or several bright red, soft, lobulated tumors that vary greatly in size and have a wide anatomic distribution with a predilection for the head and neck area. Females are slightly more affected than males. On occasion, lesions can involve deeper soft tissues or even internal organs and can be associated with high morbidity, especially if located near vital structures. Complete spontaneous resolution is common, occurring in about 70% of capillary hemangiomas by the time the patient has reached the age of 7 years.

Contrary to what was believed in the past, capillary hemangiomas are not associated with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. This syndrome, consisting of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and acute or chronic consumption coagulopathy, is mainly seen with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (usually a subcutaneous lesion, see pages 1281 and 1284) and less commonly with cavernous hemangiomas (see page 1264) and tufted angioma (see page 1261).

Histopathology. All tumors have a lobular architecture (Fig. 33-11), but microscopic features change as the lesion evolves. During their period of growth in early infancy, capillary hemangiomas show considerable proliferation of their endothelial cells. The endothelial cells are large, mitotically active, and aggregated, predominantly in solid strands and masses in which there are only a few small capillary lumina. Not uncommonly, crystalline intracytoplasmic inclusions can be seen in the endothelial cells. The lumina can be highlighted with the use of a reticulin stain. In maturing lesions, the capillary lumina are wider, and the lining endothelial cells then appear flatter (Fig. 33-12). In mature lesions, some of the lumina may be greatly dilated, focally resembling a cavernous hemangioma. In the involuting phase, there is progressive fibrosis with disappearance of the blood vessels. The vascular nature of the tumor may then be difficult to establish. However, the lobular pattern is often preserved. A worrying but entirely benign feature seen in a number of capillary hemangiomas is the presence of perineural invasion (90).

Figure 33-11 Infantile hemangioma. Involvement of the dermis and subcutis by multiple lobules composed of capillaries.

Figure 33-12 Infantile hemangioma. Mature lesion with well-formed canalized capillaries and a neighboring feeding vessel.

Pathogenesis. Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies of capillary hemangiomas have demonstrated that tumors show remarkable cellular heterogeneity. A large proportion of the cells in a given tumor are endothelial cells and pericytes, but fibroblasts and mast cells are also present (91,92). A complex interaction among these cell populations may modulate the progression and latter evolution of capillary hemangiomas (93). Juvenile hemangiomas share the same unique phenotype with human placenta (93). Immunohistochemical staining for GLUT-1 uniformly stains endothelial cells in IH (86). Gene expression analysis of these tumors has shown that their features are those of a pro-proliferative cell type with altered adhesive properties as compared to endothelial cells of the normal dermal microvasculature (94).

Differential Diagnosis. Distinction between IH and RICH and NICH is discussed in Differential Diagnosis in the section Noninvoluting Congenital Hemangioma.

Principles of Management. Oral β-blockers, mainly propranolol, are used in IHs both in the proliferative and the nonproliferative stages, but they are more successful in the former (95). The effect of β-blockers may be explained by the expression of high levels of β2-adrenoreceptors in these tumors (96). Topical β-blockers have been tried in small and superficial noncomplicated lesions (95).

Cherry Hemangioma (Senile Angioma, Campbell de Morgan Spot)

Clinical Summary. Cherry hemangiomas are bright red lesions varying in size from a hardly visible punctum to a soft, raised, dome-shaped lesion measuring several millimeters in diameter. This very common lesion, often present in large numbers, may start appearing in early adulthood, and the number of lesions increases with age. Cherry hemangiomas may occur anywhere on the skin, but the trunk and the upper limbs are the most common sites.

Histopathology. In the early stage of development, cherry hemangiomas have the appearance of true capillary hemangiomas, being composed of numerous newly formed capillaries with narrow lumina and prominent endothelial cells arranged in a lobular fashion in the subpapillary region. As the lesion ages, the capillaries become dilated. In a fully mature cherry hemangioma, numerous moderately dilated capillaries lined by flattened endothelial cells are observed. The intercapillary stroma shows edema and homogenization of the collagen. The epidermis is thinned and often surrounds most of the angioma as a collarette.

Differential Diagnosis. In its early stage, cherry hemangioma, like granuloma pyogenicum, shows capillary proliferation; however, endothelial proliferation is much less pronounced than in granuloma pyogenicum, and thus solid aggregates of endothelial cells are not seen.

Principles of Management. Simple excision, if desired.

Tufted Angioma (Angioblastoma)

Clinical Summary. Tufted angioma is a benign angiomatous condition that can be regarded as identical to the angioblastoma reported by Japanese authors (97). The angiomas affect the genders equally, usually arising between the ages of 1 and 5 years (98–100); occasionally, the lesions are present at birth (101,102), but they may develop in adults or even in old age (103). There are exceptional instances of angiomas arising in pregnancy, with regression after pregnancy (104), the occurrence in several members of a family (105), and the development of lesions after liver transplantation (106). The most common sites for the angiomatous papules and plaques are the upper trunk, neck, and proximal part of the limbs. Exceptionally, presentation may be in the oral cavity (107). The lesions usually slowly progress for several years and can eventually cover wide segments of the body; some are tender on palpation, and rare lesions regress (108). In rare cases, hypertrichosis may be seen in the skin overlying the lesion. Low-grade coagulopathy and Kasabach–Merritt syndrome are rare associations (109–111).

Histopathology. Circumscribed foci of closely set capillaries are found scattered through the dermis and occasionally reach the subcutis. At lower magnification, these discrete, ovoid angiomatous lobules or tufts have been alluded to as giving rise to a “cannonball” appearance (Fig. 33-13). The vascular nature of the tufts may not be immediately apparent, as vascular lumina are compressed by enlarged endothelial cells and contain few red blood cells. Some of the vascular tufts appear to indent lymphatic-like channels (Figs. 33-14 and 33-15). Mitotic activity and cell atypia are insignificant.

Figure 33-13 Tufted angioma. Scattered, round or ovoid dermal lobules in a typical “cannonball” distribution.

Figure 33-14 Tufted angioma. Lobule composed of bloodless capillaries surrounded by dilated crescent-shaped vascular channels.

Figure 33-15 Tufted angioma. Often, the capillaries appear poorly canalized and pericytes are prominent.

The presence of strong labeling for actin indicates a prominent pericytic component among the tumor capillaries.

Differential Diagnosis. The main importance of this uncommon angioma, especially if it develops in adults, is the differential diagnosis from Kaposi sarcoma or possibly a low-grade angiosarcoma. Endothelial cells in tufted angioma may show slight spindling but not the elongated spindle cells of Kaposi sarcoma. The discrete focal arrangement of vascular tufts having few red blood cells also differs greatly from the mature lesions of Kaposi sarcoma. The absence of cell atypia is the main distinguishing feature from angiosarcoma.

The hypertrophic cellular appearance of the tufts is similar to the angiomatous tissue in IH, but the vascular aggregates are far more massive in the latter, where they tend to replace wide segments of the dermis and fat.

Distinction from kaposiform hemangioendothelioma is sometimes difficult, particularly in small biopsies, and it has been suggested that both tumors are part of the same spectrum (112). Morphologic similarities are indeed present and their relationship appears to be supported by a similar immunohistochemical profile: the spindle cells in both neoplasms are positive for Prox1, podoplanin, LYVE-1, CD31, and CD34, while the cells within the tufts are negative for Prox1, podoplanin, and LYVE-1 and positive for CD31 and CD34 (113). Interestingly, lesional cells of IH are negative for Prox1, a feature that may be used as an aid in differential diagnosis.

Principles of Management. Surgical excision may be performed in small lesions. In cases associated with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome, different treatment modalities have been reported including vincristine (with or without embolization) (109), systemic steroids, and even propranolol. The latter has shown only very limited response (114).

Pyogenic Granuloma (Lobular Capillary Hemangioma)

Clinical Summary. Pyogenic granuloma, or lobular capillary hemangioma, is a common proliferative lesion that is often related to trauma. Typically, the lesion grows rapidly for a few weeks before stabilizing as an elevated, bright red papule, usually not more than 1 to 2 cm in size (Fig. 33-16); it may then persist indefinitely unless destroyed. Recurrence after surgery or cautery is not rare. Pyogenic granuloma most often affects children or young adults of either gender, but the age range is wide; the hands, fingers, and face, especially the lips and gums, are the most common sites (115,116). Pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva in pregnancy (epulis of pregnancy) is a special subgroup. Lesions may rarely develop within a port-wine stain (36).

Figure 33-16 Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma). Ulcerated, polypoid papular lesion.

A rare and alarming event is the development of multiple satellite angiomatous lesions at and around the site of a previously destroyed pyogenic granuloma (117,118). This usually occurs following lesions on the shoulder or upper trunk in children. Histologically, lesions that are similar to pyogenic granuloma can occur in the deep dermis, the subcutaneous tissue (119), and even within dilated venous channels (120,121). Widely scattered angiomatous lesions resembling pyogenic granulomas have also been described (122–124), sometimes in association with visceral disease.

Histopathology. The typical lesion presents as a polypoid mass of angiomatous tissue protruding above the surrounding skin. It is often constricted at its base by a collarette of acanthotic epidermis (Fig. 33-17). An intact, flattened epidermis may cover the entire lesion, but surface erosions are common. In ulcerated lesions, a superficial inflammatory cell reaction can give rise to an appearance suggestive of granulation tissue, but inflammation does not appear to be an intrinsic feature. Inflammation is usually slight in the deeper part of the lesion and may be absent when the epidermis is intact. The angiomatous tissue tends to occur in discrete masses or lobules, resembling a capillary hemangioma—hence, the preference by Mills and associates (115) for the term lobular capillary hemangioma to describe this condition (Fig. 33-18). The angiomatous tissue is surrounded by myxoid stroma containing scattered spindle- and stellate-shaped connective tissue cells and occasional mast cells. The angiomatous tissue is composed of a variably dilated network of blood-filled capillary vessels and groups of poorly canalized vascular tufts. Mitotic activity varies and can be prominent. Feeding vessels often extend into the adjacent dermis, and rare lesions show a deep component in the reticular dermis. Occasionally, foci of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia occur within the larger deep vessels. Focal epithelioid endothelial cells can sometimes be seen. Focal cytologic atypia may be present, particularly in lesions arising in mucosal surfaces such as the mouth (125). The histology of recurrent or satellite lesions is similar, but the angiomatous proliferation can extend more deeply into the dermis. Pyogenic granulomas of the subcutaneous tissue or in veins show similar histologic features but lack an inflammatory component. Intravascular lesions can so distend the veins that the surrounding muscle coat can be thinned and difficult to detect (Fig. 33-19).

Figure 33-17 Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma). Early, nonulcerated lesion with the typical epithelial collarette.

Figure 33-18 Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma). Distinctive lobules of dilated and congested capillaries in an edematous stroma.

Figure 33-19 Intravascular lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma). Some cases occur entirely in an intravenous location.

Pathogenesis. It was once assumed that granuloma pyogenicum was caused by pyogenic infection. However, the histologic picture of early lesions suggests a capillary hemangioma, and even in eroded lesions that show inflammation, the appearance mimics that of a capillary hemangioma in its deeper portions. Therefore, the term lobular capillary hemangioma has been suggested (115).

Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positive labeling of endothelial cells for vascular markers, including CD3 and ERG and also of pericytes for smooth muscle actin.

Differential Diagnosis. Both Kaposi sarcoma and angiosarcoma should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis, especially when multiple lesions are present. Elevated polypoid lesions are rare in Kaposi sarcoma; most show obvious spindle cells woven between delicate vascular spaces, unlike in pyogenic granuloma. A much greater degree of cell atypia with intraluminal spreading of malignant cells characterizes well-differentiated angiosarcomas. Focal areas of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia within a pyogenic granuloma occasionally can simulate angiosarcoma, but, even so, nuclear atypia is slight.

A further differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma is with bacillary angiomatosis, an infectious, vascular proliferation seen in HIV-infected patients and caused by Bartonella henselae or less commonly by Bartonella quintana, which are small, gram-negative rods belonging to the family Bartonellaceae (126–128) (see Chapter 21). Bacillary angiomatosis is now rarely seen in the Western world, as HIV-positive patients are treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and with prophylactic antibiotics. Clinically, and especially histologically, lesions of bacillary angiomatosis can look remarkably similar to a pyogenic granuloma. The low-power architecture in superficial lesions may be almost identical to that seen in pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 33-20). In bacillary angiomatosis, however, the endothelial cells often have abundant pale cytoplasm (Fig. 33-21), and aggregates of neutrophils are present throughout the lesion, often in relation to clumps of granular basophilic material. This basophilic material shows bacilli when stained with Warthin–Starry (Fig. 33-22) or Giemsa stains. The presence of the organism may also be detected by PCR.

Figure 33-20 Bacillary angiomatosis. Similar low-power architecture to lobular capillary hemangioma, but there is more prominent inflammation in the background.

Figure 33-21 Bacillary angiomatosis. The vascular channels are lined by pale epithelioid endothelial cells. Often, neutrophils with nuclear dust are seen in the surrounding stroma.

Figure 33-22 Bacillary angiomatosis. Warthin–Starry stain showing numerous clumps of bacilli.

Vascular granulomatous lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas occasionally arise as a complication of systemic or topical retinoid therapy, but the histology is that of nonspecific vascular granulation tissue lacking a lobular architecture (129–131). Pyogenic granuloma–like lesions have also been described during capecitabine therapy (132).

Distinction from a nodular lesion of orf or milker’s nodule may be difficult, as the low-power architecture may resemble a lobular capillary hemangioma. However, in the former, there is often prominent hyperplasia of the epidermis and the infundibular portion of the hair follicles. The prominent vascular component represents granulation tissue with only a focal lobular architecture, and the keratinocytes often show typical viral inclusions.

Principles of Management. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Most lesions are incompletely removed by a shave biopsy, and local recurrence may occur.

Cavernous Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Sharing with IH the same age, gender, and anatomic distribution, cavernous hemangioma is still less common and tends to be larger, deeper, and less well-defined than the former and shows no tendency for spontaneous regression (88,89). Rare cavernous hemangiomas may be associated with an overlying capillary hemangioma. There are two rare conditions in which numerous cavernous hemangiomas occur: Maffucci syndrome and the blue rubber bleb nevus.

Maffucci Syndrome

Clinical Summary. The outstanding features of Maffucci syndrome are dyschondroplasia resulting in defects in ossification; fragility of the bones, causing severe deformities; and osteochondromas, which may develop into chondrosarcomas (32). In addition, large, compressible subcutaneous cavernous hemangiomas and spindle cell hemangiomas (SCHs) (see page 1273) may be present at birth or appear in childhood or early adulthood.

Histopathology. See next section.

Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus

Clinical Summary. In the blue rubber bleb nevus, cavernous hemangiomas are present at birth but may subsequently increase in size and number. The hemangiomas have a distinct appearance, and most of them are protuberant, dark blue, soft, and compressible; some are pedunculated. They vary from a few millimeters to 3 cm in diameter. In addition, subcutaneous hemangiomas are felt on palpation. There are also hemangiomas in the oral mucosa, the gastrointestinal tract, and less commonly in other organs (32). Some blue rubber bleb nevi are probably telangiectatic glomangiomas in which the glomus cells are sparse.

Histopathology. Cavernous hemangiomas appear in the lower dermis and the subcutaneous tissue with large, irregular spaces containing red blood cells and fibrinous material (Fig. 33-23). The spaces are lined by a single layer of bland endothelial cells. Not uncommonly, a capillary component is present, especially in the superficial portion of a tumor. Dystrophic calcification is often present.

Figure 33-23 Cavernous hemangioma. Markedly dilated and congested vascular spaces.

Variant of Cavernous Hemangioma: Sinusoidal Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Sinusoidal hemangioma is a relatively rare variant of cavernous hemangioma (133). The lesion presents as a bluish subcutaneous mass, especially in middle-aged adults, and has a predilection for females. Although the anatomic distribution is wide, tumors often present in the breast, and in this setting, angiosarcoma is considered in the differential diagnosis.

Histopathology. Sinusoidal hemangioma is lobular and focally ill-defined with partial or total replacement of subcutaneous fat lobules. The typical feature is the presence of gaping, markedly dilated and congested, thin-walled, back-to-back vascular spaces in a sievelike or sinusoidal arrangement (Fig. 33-24). Pseudopapillary structures due to cross-sectioning of these spaces focally resemble intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Fig. 33-25). The vascular channels are lined by bland, flat endothelial cells, which can be focally prominent and mildly pleomorphic. Thrombosis, hyalinization, dystrophic calcification, and even areas of infarction can be seen in older lesions. Distinction from a well-differentiated angiosarcoma is based on the presence in the latter of an infiltrative growth pattern, cytologic atypia, and multilayering. In breast lesions, it is worth remembering that mammary angiosarcomas are always intraparenchymal.

Figure 33-24 Sinusoidal hemangioma. Congested anastomosing vascular channels with a sievelike appearance.

Figure 33-25 Sinusoidal hemangioma. Higher magnification reveals a typical sinusoidal appearance.

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Verrucous Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Verrucous hemangioma is a rare form of vascular malformation that is usually congenital and only rarely presents later in life. Most cases present as wartlike, dark blue papules or nodules, with special predilection for the distal lower limbs (Fig. 33-26). Although the majority of cases are solitary, an exceptional case with multiple lesions on different parts of the body has been reported (134). Often, cases are confused clinically and histologically with angiokeratomas, but verrucous hemangiomas always have a deep component, and recurrence after incomplete excision occurs in up to one-third of cases (135).

Figure 33-26 Verrucous hemangioma. Verrucous vascular plaques are typically seen.

In Cobb syndrome, a lesion identical to a verrucous hemangioma presents on the trunk with a dermatomal distribution and in association with an underlying meningospinal hemangioma (136). Some cases of Cobb syndrome present in association with a port-wine stain.

Histopathology. The superficial portion of a verrucous hemangioma is indistinguishable from an angiokeratoma. However, a combination of congested capillaries and cavernous-like vascular spaces is seen extending into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 33-27). These vascular spaces are lined by flattened endothelial cells and are usually surrounded by a layer of pericytes. A lobular growth pattern is often apparent in the deep component.

Figure 33-27 Verrucous hemangioma. Note the superficial component similar to angiokeratoma but with a deep component extending to the subcutaneous tissue.

Principles of Management. Surgical excision is curative only if the deep component is completely removed.

Microvenular Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. This is a relatively rare, acquired vascular lesion that usually arises as a small, reddish lesion in young to middle-aged individuals of either gender (137,138). The arms, trunk, and legs are favored sites. Multiple lesions are exceptionally seen (139).

Histopathology. Histologically, thin, branching capillaries and small venules with narrow or slightly dilated lumina are found widely throughout the dermis (Fig. 33-28). There is no obvious endothelial cell atypia or accompanying inflammation, but slight dermal sclerosis is often present (Fig. 33-29). The collagen bundles around the vascular channels appear somewhat sclerotic. A fairly constant feature in many cases is the prominent infiltration of arrector pili muscles by the proliferating vascular channels (Fig. 33-30).

Figure 33-28 Microvenular hemangioma. Irregular, branching, thin-walled venules within the dermis.

Figure 33-29 Microvenular hemangioma. Note the small venules surrounded by somewhat hyalinized collagen bundles.

Figure 33-30 Microvenular hemangioma. Prominent infiltration of the arrector pili muscle.

Differential Diagnosis. The importance of microvenular hemangioma as an acquired vascular anomaly in young persons lies in the differential diagnosis from an early or macular lesion of Kaposi sarcoma. The lymphangioma-like channels of Kaposi sarcoma are more delicate, do not contain erythrocytes, show angulated outlines, and tend to wrap around collagen bundles. Furthermore, plasma cells and other inflammatory cells are common in Kaposi sarcoma but not in microvenular hemangioma. HHV-8 is consistently positive in Kaposi sarcoma and negative in microvenular hemangioma. Only a single case of HHV-8-positive microvenular hemangioma in a patient with POEMS syndrome has been reported (140).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Hobnail Hemangioma (Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma)

Clinical Summary. Hobnail hemangioma, or targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, is a relatively uncommon vascular tumor that usually presents in the trunk or extremities of young or middle-aged adults with a male predominance (141–143). Rare cases occur in the oral mucosa and in children. Multiple lesions are exceptional. The descriptive name initially given to this tumor reflects a typical clinical appearance characterized by a small solitary lesion consisting of a brown to violaceous papule, 2 to 3 mm in diameter, surrounded by a thin, pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring. However, these features are only present in a small percentage of cases, and most often the clinical appearance is that of a red-blue or brown papule. The alternative name of hobnail hemangioma, which emphasizes a more constant special histologic feature, has therefore been proposed (see text following). Interestingly, some lesions in females change during the menstrual cycle, suggesting that there is a direct hormonal influence (144).

Histopathology. In the superficial reticular dermis, there are thin-walled, dilated, and irregular vascular spaces (Fig. 33-31) often lined by bland endothelial cells with scanty cytoplasm and rounded nuclei that protrude into the lumina and closely resemble hobnails (Figs. 33-32 and 33-33). Intraluminal papillary projections and fibrin thrombi can be seen in the superficial blood vessels (Fig. 33-33). The vascular channels in the deeper dermis become much less conspicuous and eventually disappear completely. These deeper channels are irregular and angulated, lined by flattened endothelial cells, and dissect between collagen bundles. Extensive red blood cell extravasation and inflammatory aggregates predominantly of lymphocytes are seen. In a later stage, extensive stromal hemosiderin deposition is commonly seen.

Figure 33-31 Hobnail hemangioma. Typical wedge-shaped architecture with a prominent superficial component. Note the prominent hemosiderin deposition.

Figure 33-32 Hobnail hemangioma. Irregular congested vascular channels, some of which are lined by hobnail endothelial cells.

Figure 33-33 Hobnail hemangioma. Hobnail endothelial cells and small papillary projections.

Pathogenesis. Because there is a family of vascular tumors characterized by epithelioid endothelial cells, it has been proposed that this tumor represents the benign end of the spectrum of a group of vascular tumors characterized by hobnail endothelial cells that includes papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma (PILA, Dabska tumor) and retiform hemangioendothelioma (see page 1282). The endothelial cells are positive for D2-40 (podoplanin), suggesting a lymphatic line of differentiation (145). These cells are negative for WT1, and on the basis of this finding it has been proposed that the lesion represents a lymphatic malformation (145).

Differential Diagnosis. This includes patch-stage Kaposi sarcoma, retiform hemangioendothelioma, and benign lymphangioendothelioma (see page 1293).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Epithelioid Hemangioma (Angiolymphoid Hyperplasia with Eosinophilia)

The terms epithelioid hemangioma and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia highlight the controversy about whether this entity represents a vascular neoplasm or a reactive process consequent to trauma or some other stimulus. Previously, lesions included within this group were referred to as histiocytoid hemangiomas, but this name has been abandoned because as originally proposed it included other entities that do not qualify as epithelioid hemangioma (146,147). It is not clear whether this entity represents a reactive proliferation secondary to diverse stimuli including trauma (148) or a neoplastic process, but the latter is favored. Therefore, the term epithelioid hemangioma is generally preferred to encompass vascular lesions at the benign end of the spectrum of conditions characterized by endothelial cells that have an epithelioid morphology (146,147).

Clinical Summary. Most lesions arise either superficially in the dermis or in the subcutaneous tissue or deeper tissues, although occasionally both superficial and deep tissues are affected together (149). Blood eosinophilia has been reported in up to 15% of patients (147,149). Local recurrence may be seen in up to 30% of cases.

Superficial Lesions. Young to middle-aged women are mainly affected with the development of pruritic papules (Fig. 33-34) and plaques at or around the external ear. The lesions can be numerous but are limited to one side. Typically, the clinical course is chronic over several years despite excision and other treatment modalities. Such superficial lesions were originally referred to as pseudopyogenic granuloma. Occlusion of the external auditory canal can bring patients to the attention of ear, nose, and throat specialists. Sometimes, other areas in the head and neck region, especially the occipital region and the vicinity of the temporal artery, are affected.

Figure 33-34 Epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). Single or multiple vascular papules are often present in the ear.

Lesions of Subcutaneous and Deeper Tissues. Adults are mainly affected, and there is no gender predilection. The typical lesion is a solitary, slowly growing, firm, subcutaneous swelling 2 to 10 cm in size in the head and neck region, with some predilection for the pre- or postauricular sites. Sometimes, more than one lesion arises. Most lesions are asymptomatic except for occasional pruritus. Lymphadenopathy is usually not seen. Occasionally, other body sites are affected, such as the arm, hands, axillae, or inguinal region (149–151). Rare cases have been documented in association with a traumatically induced arteriovenous fistula involving the popliteal artery (152). Origin from the radial artery has also been documented (153). The condition can persist for years, but serious complications do not occur.

Epithelioid hemangioma may also rarely occur in the oral cavity (154), tongue (155), lymph node (156), bone (157), and testis (158). A case has also been reported in an ovarian teratoma (159). Epithelioid hemangiomas occurring at sites different from the skin often lack the inflammatory component.

Histopathology. The main components of the pathology include the following:

1. Proliferation of small- to medium-sized blood vessels often showing a lobular architecture (Fig. 33-35). Many of these vascular channels are lined by greatly enlarged (epithelioid) endothelial cells (Figs. 33-36 and 33-37).

Figure 33-35 Epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). Superficial lesion from the ear showing typical lobular architecture and a prominent inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 33-36 Epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). Numerous vascular channels lined by prominent large, pink epithelioid endothelial cells and surrounded by inflammation.

Figure 33-37 Epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). Prominent endothelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and numerous eosinophils in the surrounding stroma. Note the perivascular fibrosis and numerous eosinophils.

2. A perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate composed mainly of lymphocytes and eosinophils.

3. Nodular areas of a lymphocytic infiltrate with rare follicle formation.

4. Frequent origin from a small artery or a vein. Rarely, the whole lesion is intravascular (Fig. 33-38). The condition originally described as intravenous atypical vascular proliferation likely represents a variant of intravascular epithelioid hemangioma (160).

Figure 33-38 Intravascular epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). Some cases of epithelioid hemangioma are entirely intravascular.

In superficial lesions, there is variable degree of vascular hyperplasia that can include areas in which the proliferation is almost angiomatous. A distinctive feature is the “cobblestone” appearance of enlarged endothelial cells that project into the lumina of some vessels. The nucleus of these cells is ovoid and orthochromatic without atypia or evidence of mitotic activity. Affected vessels often show endothelial cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles, which is a prominent feature of diagnostic value (Fig. 33-37). The most abnormal blood vessels are usually surrounded by stellate and spindle-shaped cells in a mucoid stroma. The associated perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually loosely scattered around the affected vessel, but it may be almost completely absent in some places. Generally, eosinophils make up 5% to 15% of the cells. Lesions with few inflammatory cells are rarely seen. Inflammatory cells also decrease markedly in late stages when a prominent fibrotic component is often present.

The epidermis above the lesions may show acanthosis or erosions owing to superficial trauma. The skin appendages are usually unaffected except for the occasional finding of follicular mucinosis (161).

In subcutaneous lesions, the inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually more massive, with a central, poorly circumscribed nodule that replaces the fat. The nodule is composed of confluent sheets of small lymphocytes and eosinophils in which a network of poorly canalized thick-walled capillaries is embedded. Satellite smaller islands of lymphoid cells with lymphoid follicles usually surround the central nodule. Eosinophils can form up to 50% of the cell population.

In about 50% of cases, evidence of involvement of medium- to large-sized arteries can be found. A variable degree of blood vessel damage occurs, with infiltration of the vessel wall by inflammatory cells and occlusion of the lumen. Partial loss of the internal elastic lamina is often seen.

Histogenesis. The etiology and pathogenesis of angiolymphoid hyperplasia is at present uncertain. Occasionally, trauma (148) or external otitis can precede the onset of the disease. Ultrastructural studies have not confirmed that the enlarged endothelial cells are developing histiocytic properties, as has been suggested. There is no relation to HHV-8, but transient angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia and Kaposi sarcoma have been described after primary infection with HHV-8 in an HIV-positive patient (162,163).

Differential Diagnosis. The proliferation of endothelial-lined channels with large irregular cells can be misinterpreted as angiosarcoma. The latter can be accompanied by a lymphocytic infiltrate, but eosinophils are rarely present. The main distinguishing feature is the presence of nuclear atypia with hyperchromatism, mitotic activity, and dissection of collagen pattern in angiosarcoma but not in epithelioid hemangioma. Distinction from the retiform hemangioendothelioma (page 1282) is easy: Angiolymphoid hyperplasia lacks a retiform growth pattern and does not show tall, narrow endothelial cells with a typical hobnail appearance, as is the case in retiform hemangioendothelioma.

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia can be distinguished from most benign angiomas or ectasias by the absence of an intrinsic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the latter. Greatly enlarged endothelial cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm rarely feature in benign angiomas, although they can be seen focally in lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma).

Persistent insect bite reactions can show overlapping histologic features with angiolymphoid hyperplasia, but the vascular proliferation is rarely as exuberant. A somewhat similar pathology can also arise as a reaction to injected vaccines (164,165). The histology is characterized by a deep lymphoid infiltrate with lymphoid follicles, tissue eosinophilia, and fibrosis. Vascular hyperplasia is however less marked than in angiolymphoid hyperplasia, and epithelioid endothelial cells are not a feature. A diagnostic feature is the presence of aluminum-containing histiocytes as demonstrated by solochrome-azurine when aluminum-adsorbed vaccines have been used (164). The presence of aluminum may also be demonstrated by energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis.

When angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia was first described in Western Europe, similarities to Kimura disease as reported in the Far East were noted. Indeed, many authors thought that both conditions might be part of one disease spectrum (166). However, more recently, most authorities emphasize differences between the two entities (166–169). Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia and Kimura disease occur most commonly in the head and neck region in adults and both share the histologic features of extensive lymphoid proliferation, tissue eosinophilia, and evidence of vascular hyperplasia. Kimura disease, however, demonstrates a wider age span, with a male predominance and a tendency for more extensive lesions to occur, often with involvement of salivary tissue and lymph nodes and at sites distant from the head and neck region. Authors from the Far East have stressed the histologic differences, the most important of which are the lesser degree of exuberant vascular hyperplasia, lacking prominent eosinophilic endothelial cells, and the absence of uncanalized blood vessels in Kimura disease. Other points of difference are eosinophilic abscesses and marked fibrosis around the lesions in Kimura disease and the absence of lesions centered around damaged arteries. There is an important association between Kimura disease and renal disease, particularly nephrotic syndrome (170).

Principles of Management. Surgery is the treatment of choice. Intralesional steroids may also be used.

Cutaneous Epithelioid Angiomatous Nodule

Clinical Summary. Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule is a recently described lesion within the spectrum of vascular tumors with epithelioid endothelial cells (171–173). It is rare and presents in adults as a papule or nodule with predilection for the trunk followed by the limbs and face. Occasionally, multiple lesions may be seen, and there is no tendency for local recurrence (174,175). An exceptional case has been described in association with a vascular malformation (176).

Histopathology. Scanning magnification shows a superficial, well-circumscribed proliferation (Fig. 33-39) often surrounded by an epidermal collarete. It is composed of sheets of epithelioid endothelial cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and a single, small nucleolus (Fig. 33-40). Cytologic atypia is absent, and mitotic figures may be focally seen (Fig. 33-41). There is little tendency for formation of vascular channels, but individual endothelial cells often contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles. There is very little stroma between tumor cells, and in the background, scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells and eosinophils may be seen.

Figure 33-39 Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule. Superficial, well-defined polypoid lesion.

Figure 33-40 Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule. Sheets of epithelioid endothelial cells with focal intracytoplasmic lumina.

Figure 33-41 Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule. Cytologic atypia is mild or absent, and there are rare mitotic figures.

Differential Diagnosis. Distinction from epithelioid hemangioma is easy, as the clinical setting in the latter is different, and lesions are composed of vascular channels lined by epithelioid endothelial cells and not by solid sheets of epithelioid endothelial cells. Bacillary angiomatosis can be distinguished from epithelioid angiomatous nodule, as lesions in the former are usually multiple, and histologically there is formation of vascular channels lined by pale epithelioid endothelial cells and associated amorphous basophilic aggregates and neutrophils, indicating the areas where the bacteria are located. Distinction from epithelioid angiosarcoma is based on the infiltrative growth pattern, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity in the latter.

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Acquired Elastotic Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. Acquired elastotic hemangioma is a recently described and distinctive relatively rare vascular lesion that develops in sun-exposed skin, mainly of the forearms and neck of middle-aged to elderly patients, with predilection for females. The clinical presentation consists of a small, red or blue, circumscribed and asymptomatic plaque (177).

Histopathology. Lesions are well-circumscribed and consist of a superficial, bandlike proliferation of capillaries in the background of solar elastosis (Figs. 33-42 and 33-43). Each capillary is surrounded by a layer of pericytes. Expression of D2-40 (podoplanin) suggests a lymphatic line of differentiation (178).

Figure 33-42 Acquired elastotic hemangioma. Superficial plaquelike proliferation of small, round vascular channels. (Courtesy of Dr. T. Mentzel, Friedrichshafen, Germany.)

Figure 33-43 Acquired elastotic hemangioma. Note the solar elastosis in the background. (Courtesy of Dr. T. Mentzel, Friedrichshafen, Germany.)

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Arteriovenous (Venous) Hemangioma (Cirsoid Aneurysm)

Clinical Summary. Arteriovenous (venous) hemangioma, or cirsoid aneurysm, usually occurs as a solitary dark red papule or nodule on the face (especially the lip) or, less commonly, on the extremities of adults, with equal gender incidence (179,180). Rare cases present in the oral cavity (181). Most of the lesions measure less than 1 cm in diameter.

Histopathology. Within a circumscribed area, usually restricted to the dermis (Fig. 33-44), densely aggregated, thick-walled and thin-walled vessels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells are observed (Fig. 33-45). The walls of the thick-walled vessels consist mainly of fibrous tissue but, in most instances, also contain some smooth muscle. Internal elastic lamina is found in very few vessels, indicating that most of the blood vessels are veins. Many vessels contain red blood cells, and thrombi are occasionally seen (181). Lesions with similar histologic appearances can be seen in the deeper soft tissues of younger patients and can be associated with hemodynamic complications due to shunting.

Figure 33-44 Cirsoid aneurysm. Polypoid superficial lesion composed of dilated, thick-walled vascular channels.

Figure 33-45 Cirsoid aneurysm. A combination of small veins and arteries.

Histogenesis. It seems likely that many of these lesions represent pure venous hemangiomas, some of which have arterialized veins (181).

Principles of Management. Simple excision is the treatment of choice.

Angiomatosis

Clinical Summary. Angiomatosis is an uncommon condition that presents exclusively in children and adolescents, and is defined as a diffuse proliferation of blood vessels affecting a large contiguous area of the body (182–184). Anatomic distribution is wide, but there is a preference for limb involvement. A typical case presents with involvement of the skin, underlying soft tissues, and even bones. Associated limb hypertrophy is common. Involvement of parenchymal organs and the central nervous system can be present. Owing to extensive involvement, surgical treatment is difficult, and recurrences are common.

Histopathology. Most tumors are composed of abundant mature fat intermixed with blood vessels in two histologic patterns (183). The most common pattern is a mixture of veins with irregular walls, cavernous vascular spaces, and capillaries. The veins often show an incomplete muscular layer, and smaller blood vessels can be seen in the walls of larger vessels. The second pattern is composed mainly of capillaries with a focal lobular architecture. Perineural invasion can be a feature in both patterns.

Spindle Cell Hemangioma

Clinical Summary. SCH is a tumor that was first described in 1986 (185) as a form of low-grade angiosarcoma. This view was challenged in subsequent publications, and until very recently a nonneoplastic process most likely related to a vascular malformation was the dominant theory. However, recent cytogenetic evidence supports a benign neoplastic process (see Pathogenesis). Gender incidence is equal, and most lesions arise in the second or third decade of life. It presents as multiple red-blue nodules in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, most commonly involving the distal aspects of the extremities with a predilection for the hands. Less frequently, lesions are seen on the head and neck. Visceral lesions do not occur, and involvement of deeper soft tissues and bone is rare (186,187). The clinical course is indolent, with multiple new lesions appearing over the years. Spontaneous regression is exceptional. In approximately 10% of cases, associated anomalies include lymphedema, Maffucci syndrome, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, and early-onset varicose veins (185,186,188,189).