Figure 8-1 Vascular injury. Hypersensitivity vasculitis showing an upper dermal small blood vessel with full-blown features of neutrophil-rich vasculitis. The specimen was obtained from a 2-day-old purpuric papule.

Secondary Vasculitis, Incidental Vasculitis, Vasculopathy, Pseudovasculitis

Terminology has been developed to describe whether vascular injury or vasculitis is primary or secondary (incidental), the degree of injury present, and conditions or disorders mimicking vasculitis (2–13). Primary vascular injury implies that the vascular insult is the predominant disease process. Secondary or incidental vascular injury indicates that an underlying nonvascular disease process is the primary pathologic process. The context of the histologic findings is important. For example, an ulcer, folliculitis, herpes virus infection, or trauma may cause vasculitic changes in nearby blood vessels. Sometimes, the primary lesion may be hidden deeper in the tissue, and additional sections may be revelatory. In many instances, distinguishing clearly between a primary and a secondary vascular insult is not possible. However, secondary vascular injury is often variable, with sparing of some vessels within the zone of tissue injury. Other indications of secondary vascular injury include deposition of fibrinoid material at the periphery of the vessel wall and focal thrombosis without significant infiltration by inflammatory cells.

The term vasculopathy or pseudovasculitis may be used to describe certain degrees of vascular alteration and injury that fail to satisfy the criteria for vasculitis (Table 8-1). Such histopathologic alterations might include hemorrhage, vascular thrombosis (hypercoagulable states), embolic phenomena with little additional evidence of vascular injury (Fig. 8-2), deposition of fibrinoid material with little or no inflammation, minimal infiltration of vessel walls with little or no leukocytoclasis, pathologic alterations of the vessel wall, vasospasm, and repetitive vascular trauma (2–13).

Figure 8-2 Vasculopathic reaction, disseminated intravascular coagulation. Pink fibrin thrombi are present within vessels that do not show evidence of damage or inflammation in their walls.

EVALUATION OF VASCULITIS

In an attempt to provide a structure for more consistency in the diagnosis of vasculitides, a consensus nomenclature and categorization has been developed. The consensus document “The International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitis” was updated in 2012 in an effort to adopt widely accepted names and definitions (13). The new naming system uses the size of the involved blood vessel (small, medium, large) as an important organizing principle (Table 8-2). Thus, the standardized nomenclature for vasculitis is based on vessel size (3,4,14,15). Large vessels are considered to include the aorta and large named arteries and veins. Medium-sized vessels include medium-sized and small arteries and veins located in the subcutis or near the dermal–subcutis junction in the skin. Small vessels include arterioles, venules, and capillaries of the dermis. Classification based on vessel size is helpful because there is some correlation with the clinical presentation. Macular purpura, palpable purpura, urticaria, vesicles and bullae, and splinter hemorrhages typically reflect small-vessel injury. Cutaneous nodules, ulcers, livedo reticularis, and digital gangrene suggest the involvement of medium-sized arteries. However, classification based on vessel size alone is of limited value in dermatopathology because most cutaneous vasculitides affect primarily small dermal vessels. Small-vessel vasculitides are subclassified according to the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate (neutrophilic/leukocytoclastic, lymphocytic, or granulomatous) in combination with data from clinical and laboratory findings. In addition, terminology has been proposed and widely accepted to replace nomenclature for two important conditions, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis and Churg–Strauss syndrome (see below and Table). A practical approach (Table 8-3) for the histopathologist in evaluating vascular inflammatory reactions is to decide whether clear-cut vascular damage is present and sufficient for a designation as vasculitis, assess the cellular composition of the inflammatory infiltrate, and define the anatomic distribution of the infiltrate within the skin. Associated findings, such as microorganisms, may narrow the differential diagnosis. During evaluation, the evanescent quality of vascular damage should be kept in mind as lesions also have life spans; a neutrophilic vasculitis with leukocytoclasia may evolve into a predominantly lymphocytic or even granulomatous process.

Names for Vasculitides Adopted by the 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus on the Nomenclature of Vasculitides

Large vessel vasculitis (LVV) |

Takayasu arteritis (TA) |

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) |

Medium-sized vessel vasculitis (MVV) |

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) |

Kawasaki disease (KD) |

Small-vessel vasculitis (SVV) |

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) |

Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener) (GPA, WG) |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome) (EGPA, CSS) |

Immune complex SVV |

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease |

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV) |

IgA vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein) (IgAV) |

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (HUV) (anti-C1q vasculitis) |

Variable vessel vasculitis (VVV) |

Behçet disease (BD) |

Cogan syndrome (CS) |

Single-organ vasculitis (SOV) |

Cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis |

Cutaneous arteritis |

Primary central nervous system vasculitis |

Isolated aortitis |

Others |

Vasculitis associated with systemic disease |

Lupus vasculitis |

Rheumatoid vasculitis |

Sarcoid vasculitis |

Others |

Vasculitis associated with probable etiology |

Hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis |

Hepatitis B virus-associated vasculitis |

Syphilis-associated aortitis |

Drug-associated immune complex vasculitis |

Drug-associated ANCA-associated vasculitis |

Cancer-associated vasculitis |

Others |

Adapted from Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(1):1–11.

Approach to Vasculitis

1. Determine whether vasculitis or vasculopathy is present or absent 2. Primary or secondary 3. Size of vessel and type a. Large b. Medium c. Small 4. Composition of infiltrate a. Neutrophilic/leukocytoclastic b. Eosinophilic c. Lymphocytic d. Histiocytic/granulomatous 5. Evaluation for infection 6. Serologic and immunopathologic evaluation a. Evaluation for ANCA, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins b. Immunofluorescence and other studies for the detection of immune complexes, for example, immunoglobulin A-fibronectin aggregates 7. Clinical context a. Cutaneous involvement only b. Extent of systemic involvement |

Histopathology alone is inadequate to classify a vasculitic disease process. Integration of data from clinical history and physical examination, other laboratory tests, and even arteriography may be critical to arrive at a final diagnosis. In particular, clinical and radiographic findings are needed to assess the degree of systemic involvement and range in size of arteries involved. Infection must be excluded via special stains, cultures, and other laboratory studies. Evidence for specific systemic conditions, such as collagen vascular diseases, hepatitis, and ingestion of certain medications or illicit drugs that may be associated with vasculitis must be evaluated.

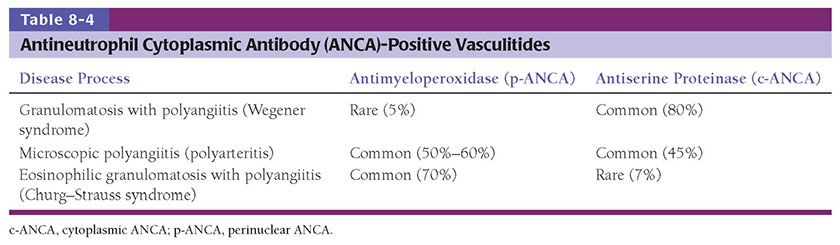

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) are serologic markers that have allowed classification of a subset of vasculitides. These markers may reflect biologic relationships between disease processes (14–18). ANCAs are best demonstrated by a combination of indirect immunofluorescence of normal peripheral blood neutrophils followed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect specific autoantibodies. Indirect immunofluorescence assays reveal two staining patterns: cytoplasmic (c-ANCA) and perinuclear (p-ANCA). ELISAs show that the majority of c-ANCAs are autoantibodies to proteinase 3, and most p-ANCAs are specific for myeloperoxidase (MPO). These antibodies are especially helpful, in combination with clinical features, in the differential diagnosis of three small-vessel vasculitides: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis, WG) (GPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome, CSS) (EGPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). GPA is usually associated with c-ANCA, MPA with either p- or c-ANCA, and EGPA with p-ANCA (see following discussion and Table 8-4). These three syndromes are termed “pauci-immune vasculitides” because vascular injury is not associated with immunoglobulin deposition in vessel walls, in contrast to the immune complex-mediated small-vessel injury seen in entities such as Henoch–Schönlein purpura. The role of ANCAs in these disease processes is unclear. ANCAs may induce vasculitis by activating circulating neutrophils and monocytes, allowing adherence to vessels, degranulation, and release of toxic metabolites. These events precipitate vascular injury. On the other hand, ANCA may be present as an epiphenomenon unrelated to the pathogenesis of these diseases.

The following sections discuss the histologic features and clinical differential diagnoses of inflammatory vascular reactions affecting the skin. Large-vessel vasculitides with cutaneous or subcutaneous findings include temporal (giant cell) arteritis and Takayasu arteritis (TA) (19–22). Vasculitis affecting medium-sized and small arteries and, in particular, small-vessel vasculitides are discussed in more detail.

VASCULITIS OF LARGE AND MEDIUM-SIZED VESSELS

Temporal (Giant Cell) Arteritis

Clinical Summary. The clinical presentation may include pain and tenderness of the forehead and sudden visual impairment. Erythema and edema of the skin overlying the involved arteries are commonly seen, and occasionally the scalp may ulcerate (19). The involved artery may be palpable. Clinical laboratory data include a significantly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although the clinical presentation is strongly suggestive of the diagnosis, a biopsy is often performed for confirmation. However, results of diagnostic tests are not always positive.

Pathogenesis. Giant cell arteritis primarily affects large or medium-sized arteries in the temporal region of elderly individuals. Although the etiology of temporal arteritis is unknown, in some cases, actinic degeneration of the internal elastic lamina may provoke granulomatous inflammation in a reaction similar to actinic granuloma. The arteritis may be unilateral or bilateral, and associated with involvement of other cranial arteries, notably the retinal arteries.

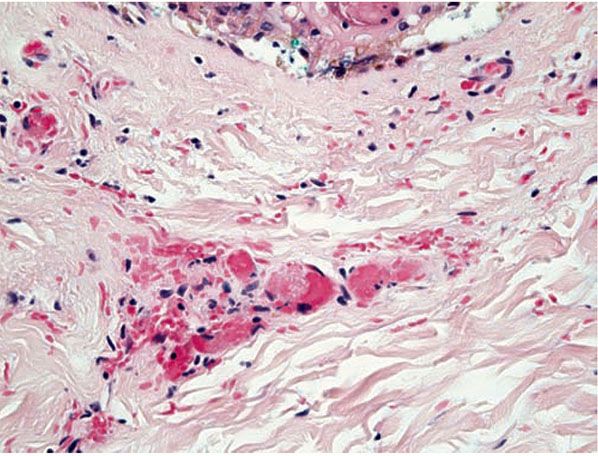

Histopathology. Involved arteries show an inflammatory process of mainly lymphocytes and macrophages that may extend throughout the entire arterial wall (Fig. 8-3). Classically, fragmentation of the lamina elastica and elastophagocytosis by multinucleated giant cells are seen. However, depending on the stage of the disease process, giant cells may not be present and the inflammatory infiltrate is often unevenly distributed. Step sections may be needed to reveal diagnostic features. In some instances, neutrophils may be present; thus some neutrophils in a background of findings otherwise typical for giant cell arthritis should not exclude the diagnosis. An elastica van Gieson stain greatly facilitates the evaluation of elastic fibers. Disruption of the internal elastic lamina is not sufficient for diagnosis because this is nonspecific. In late stages, thickening of the intima by deposits of fibrin-like material and myofibroblastic proliferation with subsequent luminal narrowing may be the only findings. Classic histologic findings may become difficult to recognize following steroid treatment. Three reliable histopathologic parameters of corticosteroid-treated temporal arteritis have been identified (23), including (a) complete or incomplete mantle of lymphocytes and epithelioid histiocytes located between the outer muscular layer and the adventitia; (b) large circumferential defects in the elastic lamina (best seen with the Movat pentachrome); and (c) absent or few small multinucleated giant cells. The CD68 immunostain may aid in the identification of rare histiocytes.

Figure 8-3 Giant cell arteritis. A and B: Biopsy of the temporal artery shows a predominantly mononuclear cell infiltrate with a few giant cells in the region of the internal elastic lamina.

Differential Diagnosis. Not all cases of arteritis involving the temporal artery represent examples of temporal arteritis. Infection-related vasculitis, connective tissue disease, and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) might enter into the differential diagnosis. The latter processes often show necrotizing neutrophilic vasculitides (depending on the stage), and diagnosis depends on serologic studies, the absence of infection, and clinical findings.

Principles of Management. Urgent treatment with high-dose systemic steroids is necessary to decrease the risk of blindness secondary to retinal artery occlusion.

Takayasu Arteritis

Clinical Summary. The principal clinical manifestations, usually in women younger than 40 years, include erythematous nodules often of the lower extremities (easily be misdiagnosed as erythema nodosum or erythema induratum) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)–like ulcers (22).

Pathogenesis. A chronic, fibrosing large-vessel vasculitis primarily involving the aorta TA may rarely have cutaneous involvement (21,22).

Histopathology. Small and medium arteries of the subcutaneous fat usually show a necrotizing panarteritis with fibrinoid necrosis and sparse inflammatory infiltrates containing lymphocytes and neutrophils. Additional findings may include granulomatous vasculitis, fibrin thrombi without vasculitis, neutrophilic abscesses, and septal and lobular panniculitis.

Differential Diagnosis. PAN, PG, and erythema nodosum may be histologically indistinguishable. Additional clinical findings and angiography should facilitate differentiation of TA from other entities.

Principles of Management. First-line treatment is with oral corticosteroids, although other immunosuppressant such as methotrexate and biologics are acceptable. For severely narrowed or acutely blocked arteries, surgery may be required.

VASCULITIS AFFECTING MEDIUM-sized AND SMALL VESSELS

Vasculitides affecting medium-sized vessels include Kawasaki syndrome, TA, infections, Buerger disease, PAN, MPA, GPA (WG), EGPA (CSS), rheumatoid vasculitis, lupus vasculitis, and giant cell (temporal) arteritis. A variety of data are used to subclassify this group, including laboratory findings such as ANCA, the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate, and the type of blood vessel (artery or vein) involved. The presence of an internal elastic lamina, visualized as a wavy layer of elastic fibers, between the intima and media characterize an artery. Another feature of an artery is a prominent concentric muscular layer. In many circumstances, the distinction between vein and artery is straightforward; however, persistent hydrostatic pressure in the lower extremities may result in hypertrophy of the medial musculature of subcutaneous veins. In this location, the muscular layer of the vein may be thicker than its arterial counterpart. Knowledge of this pitfall and an appropriately interpreted elastic stain can prevent misidentification of entities in this category (24,25).

Kawasaki Disease (Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome)

Clinical Summary. Kawasaki disease is a necrotizing arteritis that usually affects young children, with a peak incidence at 1 year of age (20); recently, Kawasaki’s has been reported in HIV-positive adults as well. Mucocutaneous findings are common and include a polymorphous exanthematous macular rash, conjunctival congestion, dry reddened lips, “strawberry tongue,” oropharyngeal reddening, and swelling of the hands and feet—especially the palms and soles. Typically, a nonpurulent cervical lymphadenopathy is associated. Desquamation of the skin of the fingers typically occurs after 1 to 2 weeks, often followed by thrombocytosis. The most serious clinical complications are related to arteritis and thrombosis of the coronary arteries.

Pathogenesis. The cause for Kawasaki disease is currently unknown, although most believe it is caused by both genetic predisposition and environmental factors, such as viral infection.

Histopathology. Cutaneous vasculitis is rare. The macular rash is usually accompanied by nonspecific histologic changes. Characteristic arteritis is typically found in visceral sites such as the coronary arteries (see Chapter 7).

Principles of Management. Administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin are currently the treatment guidelines, although aspirin must be cautiously used given its association with Reye syndrome in children with viral infection.

Superficial Thrombophlebitis

Clinical Summary. Superficial thrombophlebitis (STP) of small to medium-sized veins is a common condition usually involving the lower extremities and presents as a painful or tender erythematous cordlike structure or nodule (26). Ultrasonography usually provides the diagnosis.

Pathogenesis. STP is associated with increased risk of clotting. Affected individuals often have predisposing factors such as varicose veins, a hypercoagulable state, ingestion of oral contraceptives, or an underlying malignancy. Variants of STP include Mondor disease and superficial septic thrombophlebitis (usually secondary to peripheral venous infusion).

Histopathology. Small and medium-sized veins of the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat are involved by an acute vasculitis and thrombosis that occludes the vessel lumina. Early lesions demonstrate dense inflammatory infiltrates primarily composed of neutrophils within the vessel wall. The venous wall is significantly thickened by this influx of leukocytes and edema fluid. In later stages one may observe other inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleate giant cells within the walls of veins. Recanalization of the affected veins ultimately occurs with resolution of the process. A Gram stain is indicated for the assessment of septic STP.

Differential Diagnosis. PAN, the principal entity to be distinguished, involves medium-sized arteries rather than veins. PAN is more inflammatory and less thrombogenic than STP to the extent that thrombi are usually absent in PAN. PAN shows conspicuous fibrinoid necrosis whereas STP usually does not. An elastic tissue stain, especially if the lower extremity is biopsied, to fully characterize the involved vessels may facilitate the differentiation of PAN and STP.

Principles of Management. Local care with warm compresses and gentle compression stockings and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) for tenderness associated with clots are reasonable initial approaches. Patients at high risk of clotting may warrant anticoagulation therapy. Superficial thrombophlebitis can be an initial manifestation of a deep vein thrombosis, and consideration should be given to Doppler ultrasonography when clinically indicated.

Mondor Disease

Clinical Summary. This condition is often manifested clinically by a cordlike induration, often on the chest (27). Generalized symptoms are usually not a feature, and resolution within weeks is the norm. Ultrasonography usually provides the diagnosis.

Pathogenesis. Mondor disease is a thrombophlebitis of the subcutaneous veins of the chest region or dorsal vein of the penis (formerly termed sclerosing lymphangiitis). In a majority of cases, the etiology is unknown; however, local interference with venous flow may be a factor. Trauma, connective tissue disease, breast carcinoma (in rare cases), and a variety of other conditions have been associated.

Histopathology. In early lesions, a polymorphonuclear infiltrate may be present. Later, a sparse inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells can be observed. Most biopsied lesions show prominent subcutaneous vessels with plump endothelial cells. Characteristic organizing thrombi and thickened fibrous walls give these vessels a cordlike appearance at scanning magnification (28).

Principles of Management. Management is with warm compresses and NSAIDs.

Thromboangiitis Obliterans (Buerger Disease)

Clinical Summary. Buerger disease is a distinctive condition characterized by a segmental, thrombosing inflammatory process affecting intermediate and small arteries and sometimes veins. It may be closely related to STP (26). The vessels of the upper and lower extremities are most commonly involved. Distal extremity disease is characteristic. The condition almost exclusively affects smokers of tobacco and cannabis under 50 with the cannabis smokers tending to be younger. Cutaneous findings are manifestations of ischemic injury.

Pathogenesis. The specific cause is unknown, but it is believed that tobacco or related products may trigger an immune response in susceptible individuals, leading to vasculopathic changes and occlusion in fingers and toes.

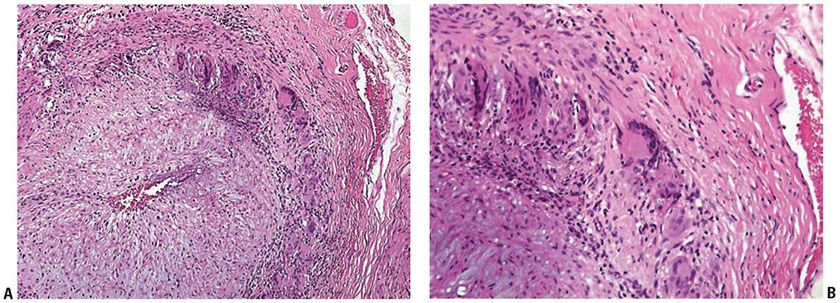

Histopathology. Active lesions are characterized by luminal thrombotic occlusion and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate of the vessel wall, characteristically with microabscesses. Later, the thrombus is organized and its lumen may be recanalized (Fig. 8-4). A granulomatous reaction may be present as well.

Figure 8-4 Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger disease). A mixed inflammatory infiltrate is present in the wall of a large vein, and its lumen is recanalized in a 35-year-old man (A, B) with associated ischemic ulceration in the distal extremity (C).

Differential Diagnosis. The histologic findings in Buerger disease are nonspecific and knowledge of the clinical scenario would most likely be required to trigger consideration of a diagnosis of Buerger disease. As smoking cessation may dramatically reverse symptoms, Buerger disease represents another example of the importance of an adequate supply of clinical information to the dermatopathologist. If extensive neutrophilia is present, infection should be excluded.

Principles of Management. Smoking cessation is essential, but may not lead to resolution of the symptoms. Notably there is some concern that nicotine replacement therapy can continue the vascular process. Drugs and procedures to help with vasodilation may be effective. Anticoagulation has not been found to be effective.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Clinical Summary. In 1866, Kussmaul and Maier (29) reported the case of a 27-year-old man with fever, abdominal pain, muscle weakness, peripheral neuropathy, and renal disease. They termed the fatal illness periarteritis nodosa, referring to nodular protuberances along the course of medium-sized muscular arteries, which histologically were characterized by inflammation predominantly at the periphery of the vessel walls with vessel-wall destruction. Ferrari noted in 1903 the more characteristic presence of inflammatory cells within all levels of the affected vessels and suggested the term polyarteritis instead of periarteritis (30). The term PAN is believed to subsume three entities: (a) classic systemic PAN, (b) cutaneous PAN, and (c) MPA (31,32). Classic PAN is a multisystem disorder characterized by inflammatory vasculitis involving arterioles and small and medium-sized arteries. According to some authors, cutaneous PAN is the only variety of PAN consistently involving the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat with diagnostic features of arteritis. Some authors maintain that if there is no evidence of systemic involvement by (skin-limited) PAN at the time of initial diagnosis, then the condition will remain confined to the skin despite a potentially prolonged clinical course with multiple recurrences (33).

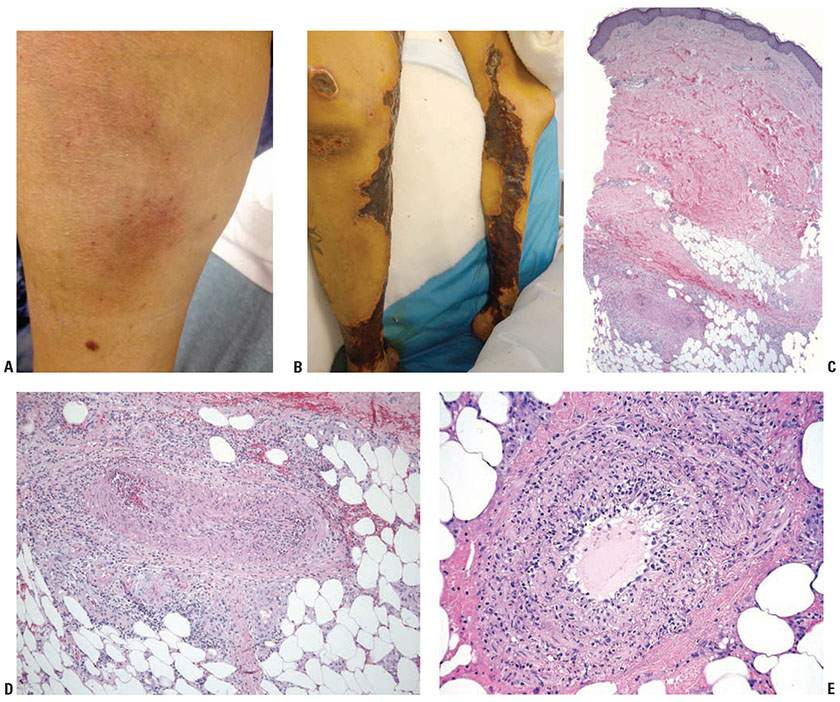

Clinical Features. PAN is more common in men than women and usually occurs between the ages of 20 and 60 years. Clinical manifestations may be dramatic and protean. Fever, malaise, weight loss, weakness, myalgias, arthralgias, and anorexia are common symptoms, reflecting the systemic nature of the disease. Other findings may reflect infarction of specific organs. Renal involvement, present in about 75% of patients, is the most common cause of death. Hematuria, proteinuria, hypertension, and azotemia may result from both infarction owing to disease of renal arteries and sometimes focal, segmental necrotizing glomerular lesions suggesting involvement of small vessels. Acute abdominal crises, strokes, myocardial infarction, and mononeuritis multiplex result from involvement of the relevant arteries. Arteriography of visceral arteries often shows multiple aneurysms that are highly suggestive of PAN. ANCAs are generally absent in patients with predominately medium-sized vessel involvement. Symptoms such as asthma, Löffler syndrome, and rashes may be related to the hypereosinophilia sometimes seen in these patients. Cutaneous manifestations include nondescript subcutaneous nodules (Fig. 8-5A) that may rarely pulsate or ulcerate, ecchymoses, livedo reticularis, bullae, papules, scarlatiniform lesions, atrophie blanche-like lesions (34), and urticaria. End-stage lesions include gangrene of toes and fingers (Fig. 8-5B). A limited form of PAN without visceral involvement may exist, but this concept is controversial (31–33). The so-called cutaneous polyarteritis nodosum may not be limited to the skin but may also affect muscle, peripheral nerve, and joints. The course of disease is described as benign but protracted with steroid dependence.

Figure 8-5 Polyarteritis nodosa. A: Early-stage lesion showing subcutaneous nodules with overlying color change probably related to telangiectasias and/or hemorrhage. B: Late-stage lesion showing epidermal necrosis and eschar formation. C: A small artery in the subcutis is surrounded and partially obliterated by a cellular inflammatory infiltrate. D: Necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis, with eosinophilic change of the vessel wall, neutrophilic infiltration, and leukocytoclasia. E: Another example of neutrophil-rich, medium-sized vasculitis with focal necrotizing features in a subcutaneous vessel in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of classic PAN is poorly understood. Direct immunofluorescence testing of skin lesions of PAN shows some immune deposits in dermal vessels. However, they may reflect a secondary event after vascular injury from another cause. ANCAs are generally absent in patients with predominantly medium-sized vessel involvement and thus are not involved in the pathogenesis of all cases of PAN.

Histopathology. The characteristic lesion of classic PAN is a panarteritis involving medium-sized and small arteries, and arterioles (22) (Fig. 8-5B,C). Even though in classic PAN the arteries show the characteristic changes in many visceral sites, affected skin often shows only small-vessel disease, and arterial involvement is typically focal. The changes affecting cutaneous small vessels are usually those of a necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). If there is a clinical presentation of cutaneous nodules, panarteritis similar to visceral lesions is usually detected. In classic PAN, the lesions typically are in different stages of development (i.e., fresh and old). Early lesions show degeneration of the arterial wall with deposition of fibrinoid material. There is partial to complete destruction of the external and internal elastic laminae. An infiltrate present within and around the arterial wall is composed largely of neutrophils, showing evidence of leukocytoclasis, although it often contains eosinophils. At a later stage, intimal proliferation and thrombosis lead to complete occlusion of the lumen with subsequent ischemia and possibly ulceration. The infiltrate also may contain a significant number of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and some plasma cells, which may extend far into the surrounding perivascular tissue and may be predominant at a certain stage. In the healing stage, there is fibroblastic proliferation extending into the perivascular area. The small vessels of the middle and upper dermis often exhibit a nonspecific lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate.

Differential Diagnosis. Vasculitis indistinguishable from PAN may be observed in infections (bacterial, e.g., pseudomonas; viral, e.g., hepatitis B or HIV), connective tissue diseases (lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis), TA, GPA (WG), EGPA (CSS), and other settings—for example, acute myelogenous leukemia. MPA can overlap considerably with PAN, as discussed later.

Principles of Management. As with all potentially systemic vasculitides, the first step is determining which organs are involved and making treatment decisions based on the severity of internal organ involvement. First-line treatments include oral corticosteroids as well as cyclophosphamide, although other immunosuppressants have been shown to be effective.

Microscopic Polyangiitis

Clinical Summary. Davson et al. (35) distinguished classic PAN from MPA. Classic PAN is to a greater degree a disease of medium-sized vessels so that ischemic glomerular lesions are common but glomerulonephritis is rare. MPA refers to a systemic small-vessel vasculitis primarily affecting arterioles and capillaries that is typically associated with focal crescentic necrotizing glomerulonephritis and presence of serum p-ANCA autoantibodies. Involvement of the small vessels of the kidneys, lungs, and skin gives MPA a particular clinical picture and separates MPA from classic polyarteritis nodosum (35–41).

Clinical Features. The majority of patients with MPA are men older than 50 years of age. Prodromal symptoms include fever, myalgias, arthralgias, and sore throat. The most common clinical feature is renal disease, manifesting as micro-hematuria, proteinuria, or acute oliguric renal failure. Although cutaneous involvement is rare in classic PAN, at least 30% to 40% of patients with MPA have skin changes. These include erythematous macules (100% in one study), livedo reticularis, palpable purpura, splinter hemorrhages, and ulcerations. Tender erythematous nodules are exceedingly rare in MPA. Pulmonary involvement without granulomatous tissue reaction occurs in approximately one third of patients. Other organ systems (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, serosal and articular surfaces) may also be affected, but this is less common. Serious clinical complications usually arise from renal and pulmonary disease.

Pathogenesis. The exact mechanism has not been elucidated, but it is believed that an overproduction of p-ANCA attracts neutrophils, which then degranulate and injure endothelial cells.

Histopathology. An LCV primarily affecting arterioles, venules, and capillaries is observed. Necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized arteries typical of classic PAN is present on occasion. Cutaneous palisading granulomatous inflammation may be seen rarely.

Differential Diagnosis. MPA and classic PAN may not be distinguishable in every case, practically speaking. Glomerulonephritis, typical skin signs, ANCA positivity, and lack of arteriography findings (aneurysms and stenoses reflecting medium-sized vessel involvement) favor MPA over classic PAN (36). MPA also tends not to be associated with viral hepatitis, in contrast to some cases of classic PAN. Biopsy findings are less useful in distinguishing between these two syndromes because the size of diseased vessels detected is highly dependent on biopsy site, size of specimens, and number of tissue samples. Thus, lack of medium-size vessel involvement in a biopsy by no means excludes classic PAN. Conversely, detection of small-vessel involvement also does not exclude classic PAN, which may show small-vessel disease. A number of cases of vasculitis show overlapping features, leading to the introduction of the term “overlapping syndrome of vasculitis” to encompass vasculitides affecting both small and medium-sized arteries (36). The differential diagnosis also includes GPA (Wegener) and other small-vessel vasculitides that are occasionally ANCA-positive, such as certain drug reactions. The granulomatous inflammation of GPA should be lacking in MPA; however, these two entities share many features, and some researchers believe that the distinction of MPA from GPA is largely artificial (37).

Principles of Management. Oral corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab have proven useful in the treatment of this condition.

GRANULOMATOUS VASCULITIS AND GRANULOMATOUS VASCULAR REACTIONS

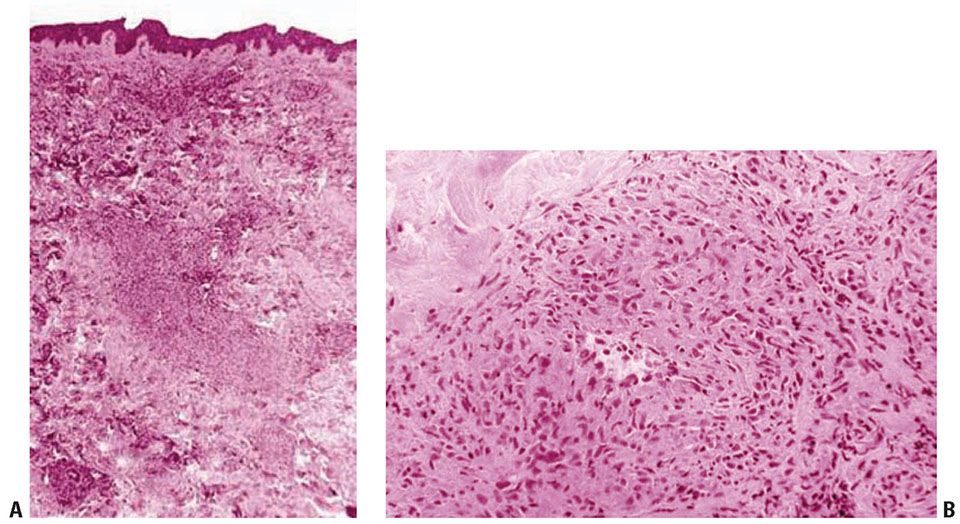

Granulomatous inflammation may be a part of many inflammatory cutaneous infiltrates and some of the granulomas may occur around blood vessels (Fig. 8-6) (1,4). When fibrinoid degeneration of the vessel wall is also observed, the process is termed granulomatous vasculitis. The main disease entities that need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a granulomatous vascular reaction are listed in Table 8-5.

Figure 8-6 Granulomatous vasculitis. Note perivascular histiocytic/granulomatous infiltrate (A) and focal vascular damage (B).

Differential Diagnosis of Granulomatous Vascular Reactions

Infection |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener syndrome) |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome) |

Polyarteritis nodosa |

Cutaneous Crohn disease |

Drug reaction |

Connective tissue disease |

Granuloma annulare |

Necrobiosis lipoidica |

Paraneoplastic phenomena |

Angiocentric T-cell lymphoma (lymphomatoid granulomatosis) |

Erythema nodosum and erythema nodosum–like reactions |

The two main disease processes in which granulomatous vasculitis has been described as prominent and fairly characteristic are GPA (Wegener) and EGPA (Churg–Strauss), which are discussed in more detail here. However, the most common cutaneous histologic finding in both diseases is LCV. The granulomatous inflammation seen in the skin in these conditions is usually is not angio-destructive.

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss Syndrome)

Clinical Summary. The classic clinicopathologic syndrome of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss), or EGPA (CSS), is characterized by asthma, fever, hypereosinophilia, eosinophilic tissue infiltrates, necrotizing vasculitis, and extravascular granuloma formation. Short of an autopsy, the classic pathologic triad of necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic tissue infiltration, and extravascular granulomas is extremely difficult to demonstrate because of the focality of the process (42). A broader definition of EGPA requiring asthma, hypereosinophilia greater than 1.5 × 109/L, and systemic vasculitis involving two or more extrapulmonary organs has been suggested. Considerable overlap with other systemic vasculitides and with other inflammatory disorders associated with eosinophils, such as eosinophilic pneumonitis, has brought the legitimacy of the EGPA into question.

Clinical Features. Despite multiple reports, EGPA appears to be rare. Between 1950 and 1995, only 120 cases were identified at the Mayo clinic (43). The incidence of EGPA is similar in males and females. It typically presents in the third or fourth decade of life. Patients tend to display several phases of disease development, from nonspecific symptoms of asthma and allergic rhinitis (prodromal phase) to a phase of hypereosinophilia with eosinophilic pneumonitis or gastroenteritis (second phase) and, finally, to systemic vasculitis (third phase). The internal organs most commonly involved are the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, and, less commonly, the peripheral nerves and heart. In contrast to PAN, renal failure is rare. The three disease phases do not always occur sequentially but may on occasion present simultaneously. There is also a limited form of allergic granulomatosis in which, in addition to preexisting asthma, the lesions are confined to the conjunctiva, the skin, and subcutaneous tissue.

Two types of cutaneous lesions occur in about two thirds of all patients: (a) hemorrhagic lesions varying from petechiae or extensive ecchymoses to palpable purpura and necrotic ulcers with associated areas of erythema (similar to Henoch–Schönlein purpura), and (b) cutaneous–subcutaneous nodules. The most common sites of skin lesions are the extremities, but the trunk may also show involvement. In some instances, the petechiae and ecchymoses are generalized. Other skin manifestations include urticaria, erythematous macules, and livedo reticularis.

Diagnostically helpful laboratory findings include an elevated peripheral eosinophil count. EPGA is also associated with ANCA positivity. Serum samples from patients with EGPA obtained during an active phase of the disease contain anti-MPO (p-ANCA) in the majority of cases (approximately 70%). The levels of anti-MPO have been found to correlate with disease activity. Anti-MPO is found less often in patients with limited forms of the disease. Anti-serine proteinase antibodies (c-ANCA) may infrequently be found in patients with CSS (approximately 7%).

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis is currently unknown. The vascular damage is secondary to deposition of antibodies in the vessel walls with subsequent migration of neutrophils, which then degranulate and damage the endothelium.

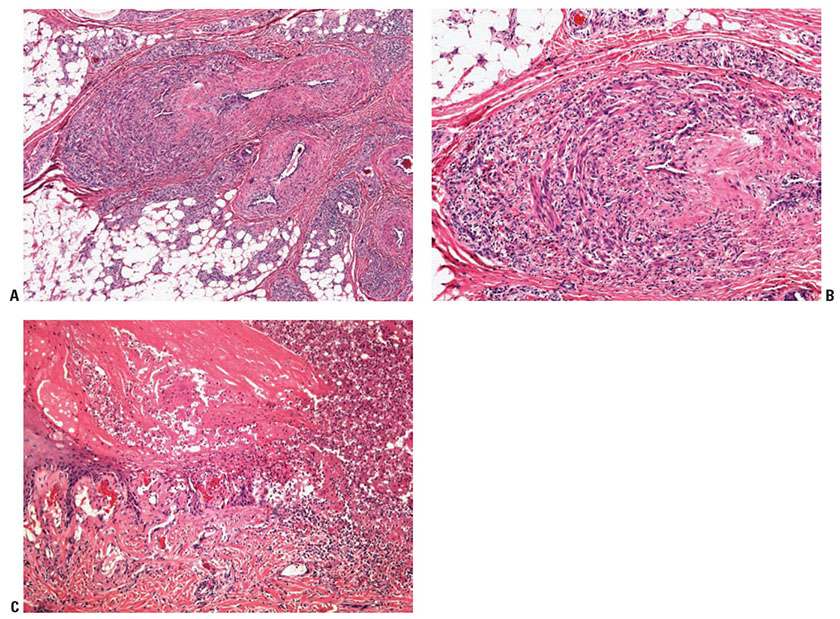

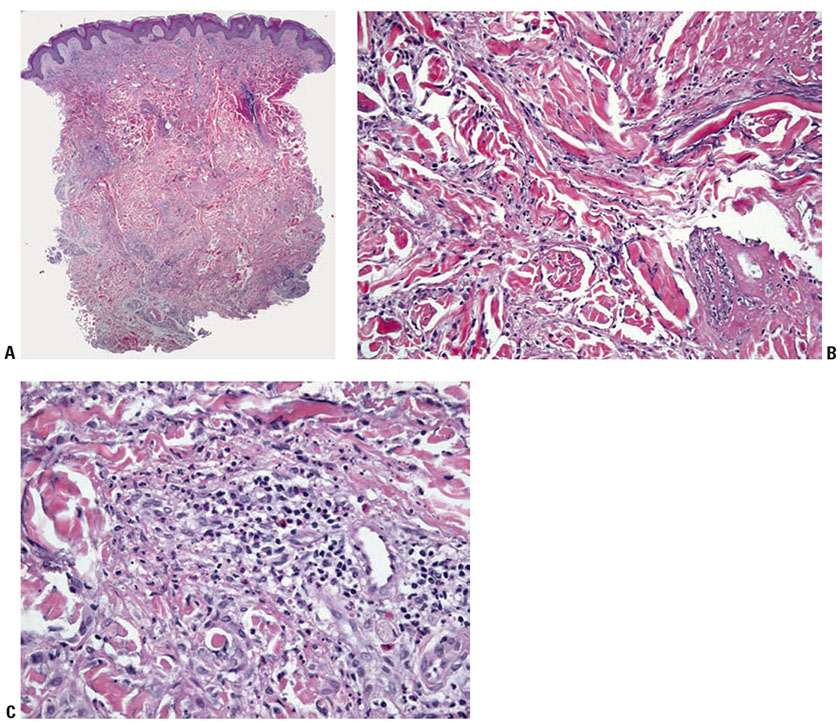

Histopathology. The areas of cutaneous hemorrhage typically show LCV. However, eosinophils may be conspicuous. In some instances, the dermis contains palisading necrotizing granulomas composed predominantly of radially arranged histiocytes and, frequently, multinucleated giant cells centered around degenerated collagen fibers (Fig. 8-7). The central portions of the granulomas contain degenerated collagen fibers and disintegrated cells, particularly eosinophils, in great numbers—the so-called “red” palisading granulomas. These palisading granulomas can be embedded in a diffuse inflammatory exudate rich in eosinophils. In the subcutaneous tissue, the granulomas may attain considerable size through expansion and confluence, giving rise to the clinically apparent cutaneous–subcutaneous nodules. Initially believed to be characteristic histologic features, these granulomas were referred to as Churg–Strauss granulomas. However, they are not always present and are not a prerequisite for the diagnosis. Moreover, more recent studies have shown that similar findings can also be observed in other disease processes, such as connective tissue diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus), GPA (Wegener), PAN, lymphoproliferative disorders, subacute bacterial endocarditis, chronic active hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis) (44). Despite the common occurrence of LCV and CS granulomas in EGPA, granulomatous arteritis may also be observed (45,46).

Figure 8-7 Palisading necrotizing granuloma. A: Scanning magnification shows a moderately dense cellular infiltrate with an ill-defined palisading pattern around areas of collagen degeneration. B: The infiltrate comprises mainly histiocytes, and collagen degeneration is prominent. C: Degenerating cells including eosinophils are present in some foci. This lesion, formerly called Churg–Strauss granuloma, is not diagnostic of any particular entity, and, in addition to granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener), may also be seen in connective tissue diseases, polyarteritis nodosa, lymphoproliferative disorders, subacute bacterial endocarditis, chronic active hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease (see text).

Differential Diagnosis. EGPA is a clinicopathologic entity. As such, a diagnosis of EGPA depends on the clinical picture of respiratory disease, particularly a history of asthma, p-ANCA positivity, and histology compatible and supportive of this diagnosis, especially granulomatous inflammation, necrotizing angiitis, and eosinophilia. The principal differential diagnosis is PAN, MPA, GPA (WG), and the conditions mentioned previously that sometimes demonstrate extravascular necrotizing granulomas. There appears to be significant overlap with GPA and PAN. Particular patients may shift from one disease category to another over time.

Principles of Management. As with all potentially systemic vasculitides, the first step is determining which organs are involved and making treatment decisions based on the severity of internal organ involvement. Like many vasculitides, high-dose corticosteroid is first-line treatment. In more severe cases, pulsed cyclophosphamide should be initiated. The management of systemic vasculitides is an area of active investigation, and an up-to-date review of the literature is recommended when treating patients with these potentially life-threatening systemic inflammatory syndromes.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Wegener Granulomatosis)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) (GPA, WG) was first recognized as a distinct clinicopathologic disease process in 1936, when Wegener reported three patients with a “peculiar rhinogenic granulomatosis.” Goodman and Churg summarized postmortem studies in 1954, from which evolved the classic triad of this clinicopathologic complex characterized by (a) necrotizing and granulomatous inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, (b) glomerulonephritis, and (c) systemic vasculitis (47). Liebow and Carrington (42) and later Deremee et al. (48) described limited variants of the disease involving the respiratory tract only.

With the recognition of an association between ANCAs and GPA, the concept of GPA has been modified and the necessity of demonstrating granulomatous inflammation as a prerequisite for the diagnosis of GPA has been challenged. A less-restrictive definition was proposed in the Third International Workshop on ANCA in 1991 (3) as Wegener vasculitis. Subsumed under this less-restrictive category are ANCA-positive patients with clinical presentations of GPA, such as sinusitis, pulmonary infiltrates, and nephritis, and documented necrotizing vasculitis, but without biopsy-proven granulomatous inflammation. Both classic WG and Wegener vasculitis are considered different manifestations of Wegener syndrome, a more generic term, which has recently been renamed “granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener),” or GPA (WG) (49).

Two thirds of patients with GPA are male, and the mean age of diagnosis is 35 to 54 years. The vast majority of patients are white. The clinical presentation is extremely variable, ranging from an insidious course with a prolonged period of nonspecific constitutional symptoms and upper respiratory tract findings to abrupt onset of severe pulmonary and renal disease. The most commonly involved anatomic sites include upper respiratory tract, lower respiratory tract, and kidneys. Other organ systems that are commonly affected include joints and skin. Migratory, polyarticular arthralgia of large and small joints is found in up to 85% of patients with GPA. Cutaneous involvement is extremely variable in different series, ranging from about 10% to more than 50% of patients. Skin involvement presents most commonly as palpable purpura. Other cutaneous manifestations include macular erythematous eruptions, papules, papulonecrotic lesions, subcutaneous nodules with and without ulceration, and PG-like ulcerations. Occasionally cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of GPA. However, because of their nonspecific appearance, they are infrequently recognized as presentations of GPA.

The development of assays for ANCA has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of GPA and the monitoring of disease activity. In a series of 106 patients with GPA, sera from 88% of the patients with active disease and 43% of the patients in remission were positive for antiserine proteinase (c-ANCA) (48).

Pathogenesis. ANCAs are believed to be the primary mediators of inflammation and result in neutrophil-mediated vessel damage. The cause of elevated ANCAs, however, remains unclear.

Histopathology. The majority of skin biopsies in patients with GPA show nonspecific histopathology, and not all of them are directly related to the pathophysiology of GPA (50–52). Such nonspecific reaction patterns include perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates. However, in about 25% to 50% of patients, cutaneous lesions have fairly characteristic histopathologic findings. The more frequent distinct reaction patterns include necrotizing/leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis and granulomatous inflammation. Minute foci of tissue necrosis are surrounded by histiocytes and are similar to lesions described in open lung biopsies from GPA patients. The palisading granulomas resembling those of EGPA (CSS) may occur, except that the center of the GPA granuloma contains necrobiotic collagen and basophilic fibrillar necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils (the “blue” palisading granulomas) (Fig. 8-7). True granulomatous vasculitis appears to be rare.

Differential Diagnosis. Other conditions causing LCV and granulomatous reactions include EGPA, metastatic Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis. Granulomatous vascular reactions may also be a manifestation of T-cell lymphomas such as angiocentric T-cell lymphoma or panniculitic T-cell lymphoma. The distinction between EGPA and GPA relies primarily on the clinical findings. In contrast to GPA, EGPA is associated with asthma, lacks lesions in the upper respiratory tract, rarely shows severe renal involvement, and typically is accompanied by eosinophilia or eosinophilic infiltrates and p-ANCA positivity. The distinction between MPA and GPA may be difficult clinically; however, MPA should lack granulomatous inflammation.

Principles of Management. Oral corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide are standard treatments, with newer data supporting use of rituximab as early therapy for patients with GPA. Plasmapheresis, azathioprine, and other immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies have been found to be beneficial as well.

SMALL-VESSEL NEUTROPHILIC/LEUKOCYTOCLASTIC VASCULITIS

A large number of different disease processes can be accompanied by small-vessel vasculitis with a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate. The clinical and histologic manifestations are thus fairly nonspecific (Fig. 8-8). The main diseases to be considered are listed in Table 8-6 (3–14,52,53).

Figure 8-8 A: Extensive palpable purpura associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. (Courtesy of Melvin Chiu, MD.) B: Close-up view of lesions of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. C: Hypersensitivity vasculitis showing an upper dermal small blood vessel with neutrophil-rich vasculitis and other adjacent postcapillary venules with a perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate without features of vasculitis. The specimen was obtained from a 6-day-old purpuric macule.

Differential Diagnosis of Cutaneous Neutrophilic Small-Vessel Vasculitis, Categorized on the Basis of Proposed Pathogenic Mechanisms

Infection |

Bacterial (gram-positive/gram-negative organisms, mycobacteria, spirochetes) |

Rickettsial |

Fungal |

Viral |