Introduction668

EPIDERMAL AND OTHER NEVI

EPIDERMAL NEVUS

Histopathology

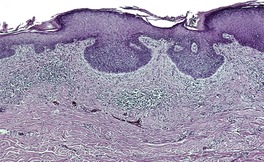

Fig. 31.1

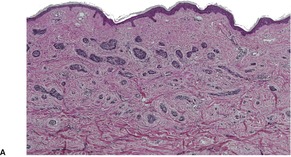

Fig. 31.2

INFLAMMATORY LINEAR VERRUCOUS EPIDERMAL NEVUS

Histopathology

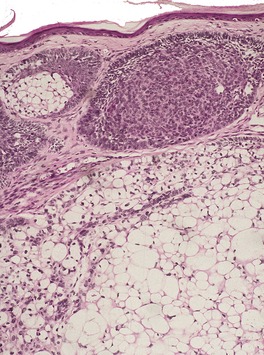

NEVUS COMEDONICUS

Histopathology

FAMILIAL DYSKERATOTIC COMEDONES

Histopathology

PSEUDOEPITHELIOMATOUS HYPERPLASIA

GRANULOMA FISSURATUM

Histopathology

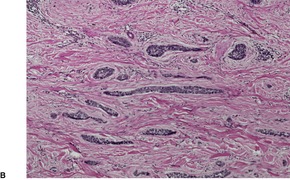

Fig. 31.3

PRURIGO NODULARIS

Histopathology165. and 181.

Fig. 31.4

Fig. 31.5

ACANTHOMAS

EPIDERMOLYTIC ACANTHOMA

WARTY DYSKERATOMA

ACANTHOLYTIC ACANTHOMA

Histopathology198

Fig. 31.6

SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS

Histopathology197. and 235.

Fig. 31.7

Fig. 31.8

Fig. 31.9

Electron microscopy

Leser–Trélat sign

Histopathology287

DERMATOSIS PAPULOSA NIGRA

Histopathology313

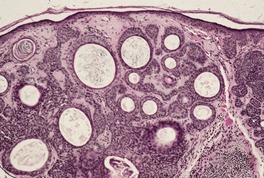

Fig. 31.10

MELANOACANTHOMA

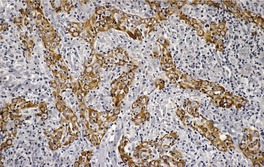

Histopathology316.319. and 323.

CLEAR CELL ACANTHOMA

Histopathology328.332. and 350.

Fig. 31.11

CLEAR CELL PAPULOSIS

Histopathology

LARGE CELL ACANTHOMA

Histopathology369. and 370.

Fig. 31.12

EPIDERMAL DYSPLASIAS

ACTINIC KERATOSIS

Treatment of actinic keratosis

Histopathology467

Fig. 31.13

Electron microscopy

ACTINIC CHEILITIS

Histopathology503. and 508.

ARSENICAL KERATOSES

Histopathology517. and 518.

Fig. 31.14

PUVA KERATOSIS

Histopathology

INTRAEPIDERMAL CARCINOMAS

BOWEN’S DISEASE

Treatment of Bowen’s disease

Histopathology379. and 653.

Fig. 31.15

Fig. 31.16

Fig. 31.17

Electron microscopy704

ERYTHROPLASIA OF QUEYRAT

INTRAEPIDERMAL EPITHELIOMA (JADASSOHN)

MALIGNANT TUMORS

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

Nomenclature

Clinical aspects

Etiology

Genetic aspects

Cell of origin

Treatment of basal cell carcinoma

Histopathology1035

Fig. 31.18

Nodular (solid) type

Micronodular type

Fig. 31.19

Cystic type

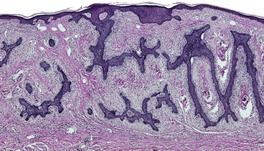

Superficial (multifocal) type

Fig. 31.20

Pigmented type

Adenoid type

Infiltrating type

Fig. 31.21

Sclerosing type

Keratotic type

Infundibulocystic type

Fig. 31.22

Metatypical type

Fig. 31.23

Basosquamous carcinoma

Fibroepithelioma

Fig. 31.24

Miscellaneous variants

Fig. 31.25

Electron microscopy

Recurrences

Metastases

NEVOID BASAL CELL CARCINOMA SYNDROME

Histopathology1349

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Clinical aspects

Occurrence in organ transplant recipients

Etiology

Genetic aspects

Unitarian theory of squamous cell carcinoma

Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma

Histopathology

Fig. 31.26

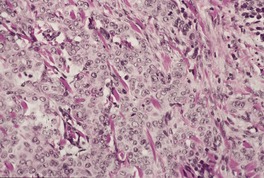

Spindle-cell squamous carcinoma

Fig. 31.27

Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 31.28

Pseudovascular squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 31.29

Other variants of squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 31.30

Fig. 31.31

Fig. 31.32

Electron microscopy

Recurrences and metastases

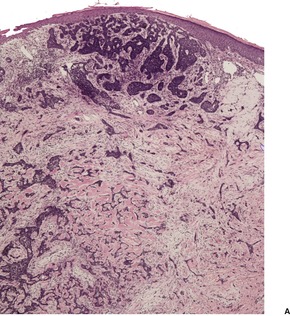

VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA

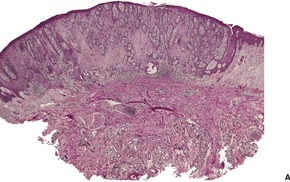

Histopathology1735.1744.1748. and 1772.

Fig. 31.33

ADENOSQUAMOUS CARCINOMA

Histopathology1789. and 1790.

Fig. 31.34

MUCOEPIDERMOID CARCINOMA

Histopathology

CARCINOSARCOMA (METAPLASTIC CARCINOMA)

Histopathology

Fig. 31.35

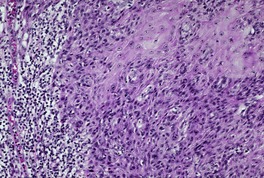

LYMPHOEPITHELIOMA-LIKE CARCINOMA

Histopathology1829

Fig. 31.36

Fig. 31.37

MISCELLANEOUS ‘TUMORS’

CUTANEOUS HORN

Histopathology

STUCCO KERATOSIS

Histopathology1869.1870. and 1873.

CLAVUS (CORN)

Histopathology

Fig. 31.38

CALLUS

Histopathology

ONYCHOMATRIXOMA

Histopathology

KERATOACANTHOMA

Giant keratoacanthoma

Abortive keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum (multinodular keratoacanthoma)

Subungual keratoacanthoma

Multiple keratoacanthomas

Etiology

Treatment of keratoacanthoma

Histopathology

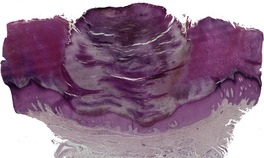

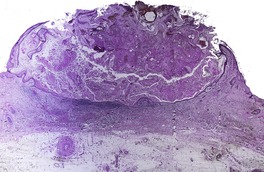

Fig. 31.39

Fig. 31.40

Fig. 31.41

Fig. 31.42

Fig. 31.43

Fig. 31.44

Fig. 31.45

Fig. 31.46

Fig. 31.47

Distinction of keratoacanthoma from squamous cell carcinoma

Behavior of keratoacanthomas

Metastasis

Regression

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Tumors of the epidermis

Some authors use the term ‘epithelial nevus’ or ‘epidermal nevus’ as a group generic term to cover malformations of adnexal epithelium, as well as those involving the epidermis alone (see below).1. and 2. The term ‘epidermal nevus’ is used here in a restricted sense and does not include organoid, sebaceous, eccrine, and pilar nevi. These are considered with the appendageal tumors in Chapter 33. An exception has been made for nevus comedonicus, an abnormality of the infundibulum of the hair follicle. It is considered here because its histological appearance suggests an abnormality of the epidermis, rather than of appendages. Furthermore, the report of the coexistence of nevus comedonicus and an epidermal nevus suggests that the two entities are closely related. 3 The nevus comedonicus syndrome is regarded as a variant of the epidermal nevus syndrome; it has also been grouped with the organoid nevus (see p. 806).

The nomenclature of epidermal nevi has become confusing with some authors using the term as a group generic expression to cover all hamartomatous lesions derived from epidermal components, and resulting from mutations in early embryonic stages of development. They are then subclassified on the basis of their main constituent. The term ‘epidermal nevus’, as used here, is called keratinocyte epidermal nevus (OMIM 162900) in this new system. 4 Some cases have several components (keratinocyte, sebaceous, and eccrine), highlighting the difficulties created by this new nomenclature. 5

An epidermal nevus is a developmental malformation of the epidermis in which an excess of keratinocytes, sometimes showing abnormal maturation, results in a visible lesion with a variety of clinical and histological patterns. 6 They are hamartomatous lesions with an incidence of approximately 1 in 1000 live newborns. 7 Such lesions are of early onset, with a predilection for the neck, trunk, and extremities.8. and 9. There may be one only, or a few small warty brown or pale plaques may be present. A facial variant that was bilateral and symmetric has been reported. 10 At other times the nevus takes the form of a linear or zosteriform lesion, or just a slightly scaly area of discoloration.6.11. and 12. The acanthosis nigricans form of epidermal nevus, which may be zosteriform or oriented along Blaschko’s lines, appears to be a mosaic form of acanthosis nigricans. 13 Various terms have been applied, not always in a consistent manner, to the different clinical patterns. 12 The term ‘nevus verrucosus’ (verrucous epidermal nevus) has been used for localized wart-like variants,14.15. and 16. and ‘nevus unius lateris’ for long, linear, usually unilateral lesions on the extremities. 17‘Ichthyosis hystrix’ refers to large, often disfiguring nevi with a bilateral distribution on the trunk.18. and 19. Mosaicism for chromosome 6 has been found in skin fibroblasts from skin attached to an epidermal nevus. 20 Much more common are mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), an abnormality found also in acanthosis nigricans and some seborrheic keratoses. 21

Various tumors have been reported arising in epidermal nevi, as a rare complication. These include basal cell22 and squamous cell carcinomas,23.24. and 25. as well as a keratoacanthoma. 26 Acne developed at puberty in one epidermal nevus. 27 Verrucous epidermal nevus (nevus verrucosus) has been reported in association with an organoid nevus (nevus sebaceus). 28 Colocalization with psoriasis has also been reported. 29

The term ‘epidermal nevus syndrome’ (OMIM 163200) refers to the association of epidermal nevi with neurological, ocular, and skeletal abnormalities, such as epilepsy, learning disability, hypophosphatemic vitamin D-resistant rickets, 30 cardiac arrhythmia, 31 cataracts, kyphoscoliosis, and limb hypertrophy; there may also be cutaneous hemangiomas.2.7.32.33.34.35.36.37.38.39.40.41.42. and 43. There are potentially many different epidermal nevus syndromes based on variable genetic mosaicism.9.44. and 45. The nevus comedonicus syndrome, CHILD syndrome (see p. 256), Proteus syndrome (see below), Becker’s nevus syndrome (OMIM 604919), and Schimmelpenning syndrome (OMIM 163200) have all been regarded as variants of epidermal nevus syndrome. 46 Cases with more traditional epidermal nevi have been called keratinocytic epidermal nevi. 47 Systemic cancers of various types may arise at a young age in those with the syndrome.48. and 49. The epidermal nevi, which are often particularly extensive in patients with the syndrome, may be of any histological type.50.51. and 52. Epidermal nevi have also been reported in association with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, 53 and with the Proteus syndrome (OMIM 176920), a very rare disorder with various mesodermal malformations.54.55.56.57.58. and 59. Other cutaneous manifestations of this disorder include lipomas, vascular malformations, cerebriform connective tissue nevi on the soles of the feet, and partial lipohypoplasia.60.61. and 62. It has been claimed that cases of Proteus syndrome with PTEN mutations63 are a separate entity and not Proteus syndrome. 59 Seven patients previously regarded as Proteus syndrome have been reclassified as a new syndrome. They featured congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations and epidermal nevi (CLOVE syndrome). 64

Topical treatments such as retinoic acid or 5-fluorouracil have been used to remove the keratotic surface of epidermal nevi and improve the cosmetic appearance. Cryotherapy is often followed by recurrence. Small lesions can be removed by surgical excision. Laser therapy can be used for larger lesions. Scarring may follow the use of the CO2 laser, but the pulsed erbium:YAG laser seems to give excellent cosmetic results. 65

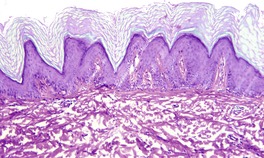

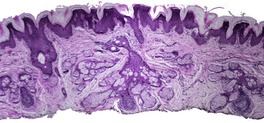

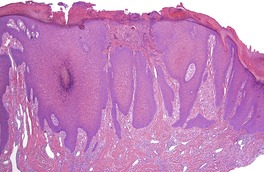

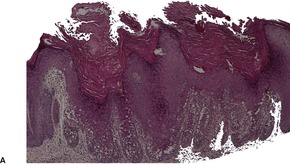

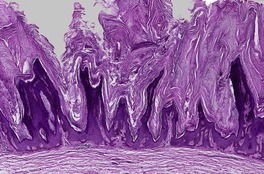

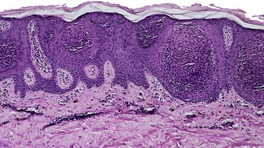

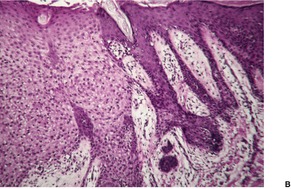

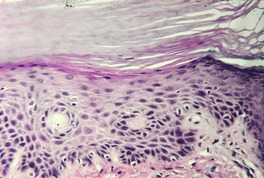

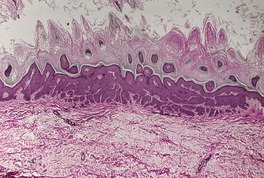

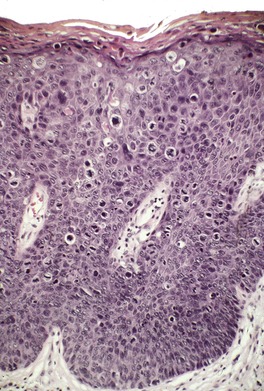

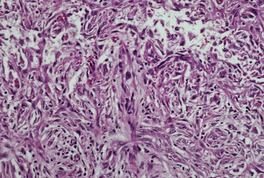

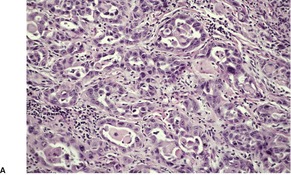

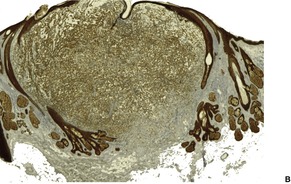

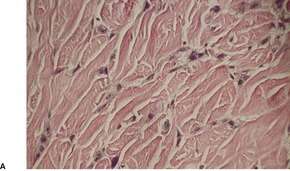

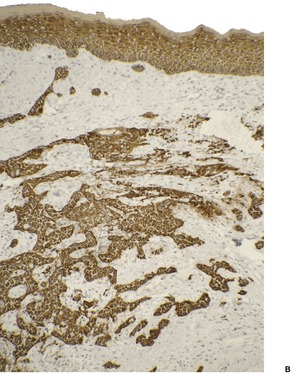

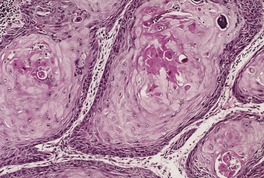

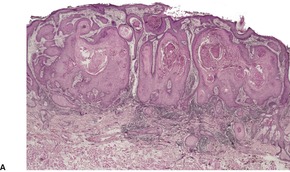

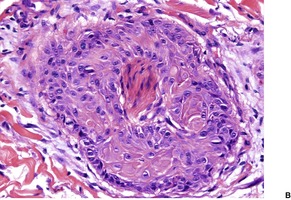

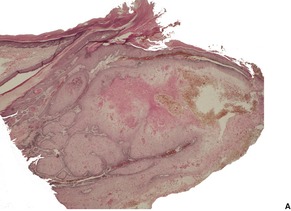

At least 10 different histological patterns have been found in epidermal nevi (Fig. 31.1 and Fig. 31.2).6. and 12. More than one such pattern may be present in a given example. In over 60% of cases the pattern is that of hyperkeratosis, with papillomatosis of relatively flat and broad type, together with acanthosis. There is thickening of the granular layer and often a slight increase in basal melanin pigment. This is the so-called ‘common type’ of epidermal nevus.

Epidermal nevus. There is papillomatosis and acanthosis with overlying laminated hyperkeratosis. (H & E)

Epidermal nevus. This variant resembles acanthosis nigricans. (H & E)

Less frequently the histological pattern resembles acrokeratosis verruciformis, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (OMIM 600648) or seborrheic keratosis.6. and 12. Epidermal nevi with a seborrheic keratosis-like pattern often have thin, elongated rete ridges with ‘flat bottoms’, a feature not usually seen in seborrheic keratoses. Rare patterns include the verrucoid, porokeratotic, focal acantholytic dyskeratotic,66.67.68.69. and 70. acanthosis nigricans-like,13. and 71. Hailey–Hailey disease-like, 72 and the incontinentia pigmenti-like (verrucous phase) variants. 73 A lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate has also been reported in an epidermal nevus, although usually the dermis is devoid of inflammatory cells. 74 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus and nevus comedonicus are regarded as distinct entities, although they are sometimes included as histological patterns of epidermal nevus.

The epidermis overlying an organoid nevus (see p. 806) frequently will show the histological picture of an epidermal nevus. In such cases this is usually of the common type.

Also known by the acronym of ILVEN, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a specific clinicopathological subgroup of epidermal nevi which most often presents as a pruritic linear eruption on the lower extremities.2.75.76.77.78. and 79. The lesions are usually arranged along the lines of Blaschko. 80 The condition is of early onset, usually in the first 6 months of life. 81 Familial occurrence is rare. 82 Asymptomatic variants and widespread bilateral distribution have been reported;83. and 84. most cases are unilateral. ILVEN has been described in association with the epidermal nevus syndrome (see above), 85 and in a burn scar. 86

The lesions resemble linear psoriasis both clinically and histologically; in this context it must be noted that the existence of a linear form of psoriasis has been questioned.87. and 88. Interestingly, the epidermal fibrous protein isolated from the scale in ILVEN is different from that found in psoriasis.89. and 90. Because of the similarities between these two conditions etanercept has been used to treat widespread ILVEN. 91

The most widely used treatment is intralesional or potent topical corticosteroids. Both provide temporary relief at best. 81 Topical calcipotriol may be of some benefit, but it should be used with caution in children. 81 Destructive therapies have also been disappointing. Small lesions can be surgically removed.

There is psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying areas of parakeratosis, alternating with orthokeratosis. Beneath the orthokeratotic areas of hyperkeratosis there is hypergranulosis, often with a depressed cup-like appearance; the parakeratosis overlies areas of agranulosis of the upper epidermis. 92 The zones of parakeratosis are usually much broader than in psoriasis. Focal mild spongiosis with some exocytosis and even vesiculation may be seen in some lesions. 93 There is also a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. A dense lichenoid infiltrate was present in one case, perhaps representing the attempted immunological regression of the lesion. 94

A case reported as ILVEN of the penis and scrotum, and associated with ipsilateral undescended testicle is probably a variant of epidermal nevus with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, based on the published photomicrographs. 95

The immunohistochemical features of ILVEN differ from those found in epidermal nevi. 96 This may simply be a reflection of the inflammatory component of ILVEN.

Nevus comedonicus (comedo nevus) is a rare abnormality of the infundibulum of the hair follicle in which grouped or linear comedonal papules develop at any time from birth to middle age.97.98. and 99. Approximately 50% of cases are evident at birth. 100 They are usually restricted to one side of the body, particularly the face, trunk, and neck.101.102. and 103. Rare clinical presentations have included penile, 104 scalp, 105 palmar,106.107. and 108. bilateral, 109 and verrucous lesions. 106 Extensive lesions are an uncommon manifestation. 110 Rarely, abnormalities of other systems such as the skeletal and neurological systems are present, indicating that a nevus comedonicus syndrome, akin to the epidermal nevus syndrome, occurs.81.111.112.113.114. and 115. It is regarded as a subset of the epidermal nevus syndrome. 47 Accessory breast tissue was present in one patient. 116 Nevus comedonicus has been reported in association with hidradenoma papilliferum and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. 117 All lesions were in the female genital area. 117 Inflammation of the lesions is an important complication, resulting in scarring.109.118.119. and 120.

Topical ammonium lactate, urea, and retinoids have all been tried at some time to treat nevus comedonicus. 115 Antibiotics are required for infected lesions. Small lesions can be excised. For large lesions the treatment of choice remains to be determined. 115 The erbium:YAG laser is a possibility for these larger lesions. 121

There are dilated keratin-filled invaginations of the epidermis. An atrophic sebaceous or pilar structure sometimes opens into the lower pole of the invagination. 122 A small lanugo hair is occasionally present in the keratinous material. Filaggrin expression is increased in the closed comedones seen in this condition. 123 Inflammation and subsequent dermal scarring are a feature in some cases. A tricholemmal cyst has also been reported arising in a comedo nevus. 124

The epithelial invagination in some cases of palmar involvement has opened into a recognizable eccrine duct.107. and 125. Cornoid lamellae have also been present.126.127. and 128. It has been suggested that these are cases of eccrine hamartomas, akin to nevus comedonicus and unrelated to porokeratosis. 129

Rare histological patterns associated with comedo nevus-like lesions have included a basal cell nevus, 130 a linear variant with underlying tumors of sweat gland origin, 131 and a variant with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis in the wall of the invaginations. 132 Epithelial proliferation, resembling that seen in the dilated pore of Winer, has been noted. 133 A form with dyskeratosis, accompanied often by acantholysis in the wall, is regarded as a distinct entity – familial dyskeratotic comedones (see below).

Familial dyskeratotic comedones is a rare autosomal dominant condition in which multiple comedones develop in childhood or adolescence, sometimes in association with acne.134.135.136. and 137. Sites of involvement include the trunk and extremities and, uncommonly, the palms and soles, the scrotum and the penis.134. and 138. This entity appears to be distinct from nevus comedonicus, and also from the rare condition of familial comedones.139. and 140.

A follicle-like invagination in the epidermis is filled with laminated keratinous material. Dyskeratotic cells are present in the wall of the invagination, particularly in the base. This is associated with acantholysis, which may, however, be mild or inapparent. 135

Pseudoepitheliomatous (pseudocarcinomatous) hyperplasia is a histopathological reaction pattern rather than a disease sui generis.141.142. and 143. It is characterized by irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis which also involves follicular infundibula and acrosyringia.141. and 144. This proliferation occurs in response to a wide range of stimuli comprising chronic irritation, including around urostomy and colostomy sites, 145 trauma, the use of permanent make-up, 146 a tattoo site, 147 cryotherapy, chronic lymphedema, and various dermal inflammatory processes such as chromomycosis, sporotrichosis, aspergillosis, pyodermas, bacillary angiomatosis, and actinomycosis.142.143.148. and 149. The lesions occurring around urostomy and colostomy sites take the form of pseudoverrucous papules and nodules. 150 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV)-related human papillomaviruses have been reported in these lesions, but specifically excluded in other cases. 151 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia has been reported in the chronic verrucous lesions that develop in immunocompromised patients who develop herpes zoster/varicella infection (see p. 618). It may also develop in the halogenodermas and in association with chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis, 152 Spitz nevi, malignant melanomas, overlying granular cell tumors, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, 153 and CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. 154 The term ‘pseudorecidivism’ has been used for the pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that sometimes develops a few weeks after treatment, by various methods, 155 of a cutaneous tumor.

On microscopic examination there are prominent, somewhat bulbous, acanthotic downgrowths which in many instances represent expanded follicular infundibula. 141 Ackerman stresses that these structures are epidermal in origin and not follicular. 156 The hyperplasia is not as regular as that seen in psoriasiform hyperplasia. The cells have abundant cytoplasm, which is sometimes pale staining. Unlike squamous cell carcinoma there are few mitoses and only minimal cytological atypia. Aneuploidy is present in a small number of cases. 157 Where the process overlies dermal inflammation, transepidermal elimination of the inflammatory debris may occur, resulting in intraepidermal microabscesses.

In addition to those conditions already mentioned, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia occurs in granuloma fissuratum and prurigo nodularis: these conditions are discussed below.

Granuloma fissuratum158 (acanthoma fissuratum, 159 spectacle-frame acanthoma160) is a firm, flesh-colored or pink nodule with a grooved central depression which develops at the site of focal pressure and friction from poorly fitting prostheses such as spectacles.159. and 161. Accordingly, such lesions are found on the lateral aspect of the bridge of the nose near the inner canthus, 162 in the retroauricular region, 158 and, rarely, on the cheeks.

A similar lesion develops in the mouth as a result of poorly fitting dentures. The lesions are painful or tender and they may ulcerate. Clinically they resemble basal cell carcinomas, although the central groove corresponding to the point of contact with the spectacle frame usually allows a correct diagnosis to be made. 163 Lesions heal within weeks of correction of the ill-fitting prosthesis.

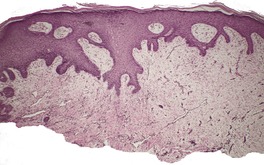

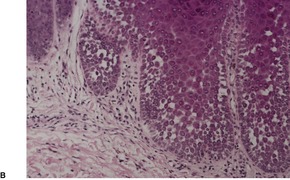

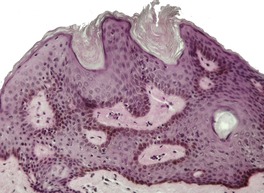

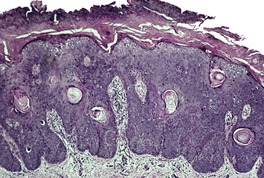

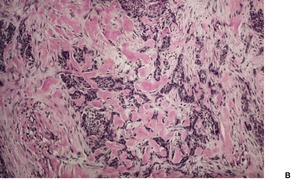

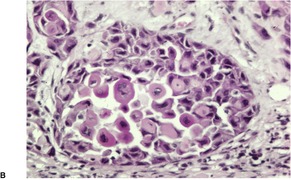

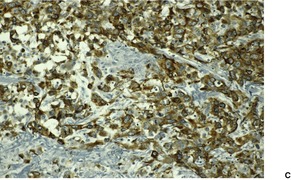

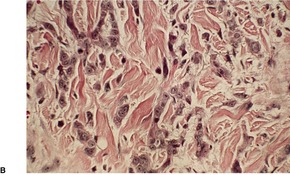

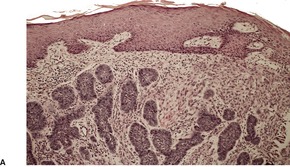

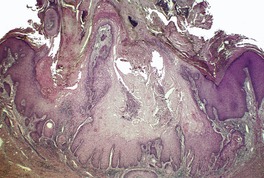

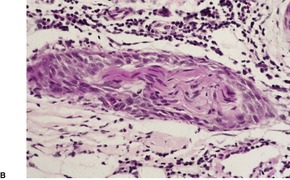

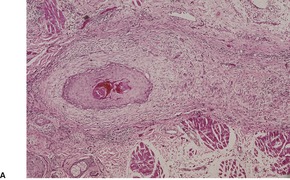

The lesion is characterized by marked acanthosis of the epidermis with broad and elongated rete pegs (Fig. 31.3). There is a central depression, corresponding with the groove noted macroscopically, and here the epidermis is attenuated and sometimes ulcerated.158. and 160. There is mild hyperkeratosis and often a prominent granular layer overlying the acanthotic epidermis; there may be parakeratosis and mild spongiosis in the region of the groove or adjacent to it.

Granuloma fissuratum. There is focal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. (H & E)

The dermis shows telangiectasia of the small blood vessels with an accompanying chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, which is usually mild and patchy. The infiltrate includes plasma cells, lymphocytes, and some histiocytes. There is focal fibroblastic activity and focal dermal fibrosis, with mild hyalinization of collagen beneath the groove. There may be mild edema of the superficial dermis.

Prurigo nodularis is an uncommon disorder in which there are usually numerous persistent, intensely pruritic nodules. There is a female predominance. In a recent series of 72 cases, the ages ranged from 15 to 92 years, with a median age at presentation of 55 years. 164 They involve predominantly the extensor aspects of the limbs, often symmetrically, but they may also develop on the trunk, face, scalp, and neck.165.166.167. and 168. The nodules are firm, pink, and sometimes verrucous or focally excoriated. They are approximately 5–12 mm in diameter and range from few in number to over 100. 165 Solitary lesions also occur. The intervening skin may be normal or xerotic; sometimes there is a lichenified eczema. 165 There may be an underlying cause for the pruritus, such as a metabolic disorder, 164 bites, folliculitis, the pruritic eruption of HIV infection,169. and 170. or atopic state.165. and 171. It has arisen in a healed herpes zoster scar, an isotopic response. 172 Mycobacteria have been cultured from, or demonstrated in, tissue sections in nearly one-quarter of cases in one study. 173 The significance of this finding is uncertain; it has not been confirmed. The tretinoin derivative etretinate, used in the treatment of a range of skin conditions, has been incriminated in several cases. 174 Stress is sometimes a factor, although psychological factors may have been overstressed in the past. 175 Prurigo nodularis is regarded by some authors as an exaggerated form of lichen simplex chronicus (see p. 86). Substance P-immunoreactive nerves, and calcitonin gene-related peptide are markedly increased in lesions of prurigo nodularis. 176

Capsaicin, an alkaloid which interferes with the perception of pruritus and pain by depletion of neuropeptides in small sensory nerves in the skin, has been used successfully in the treatment of prurigo nodularis. 177 Thalidomide has also been used, but care should be taken to exclude an underlying peripheral neuropathy before commencing this drug.178.179. and 180. Topical and intralesional steroids, emollients, topical antipruritics, doxepin, and cryotherapy are other treatments that have been used.164. and 176.

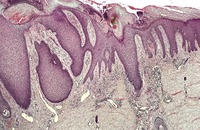

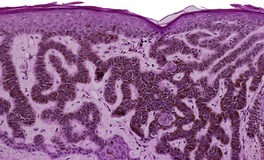

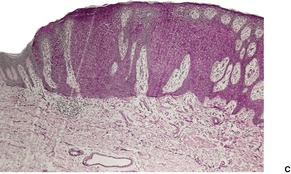

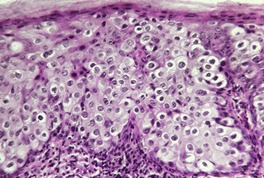

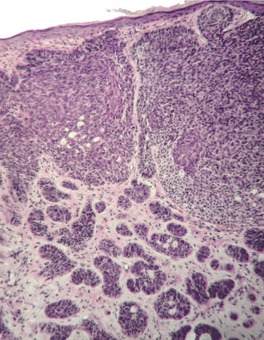

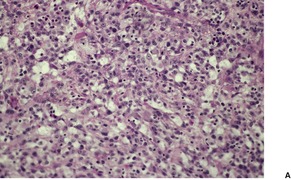

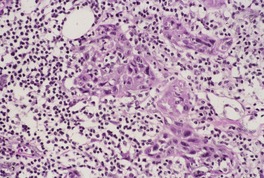

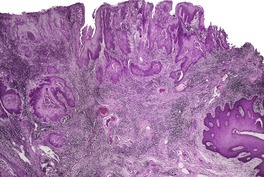

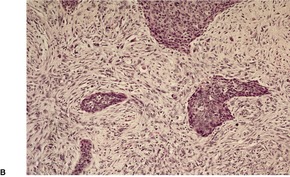

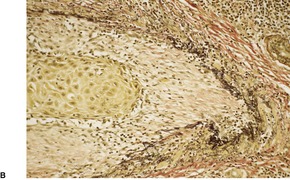

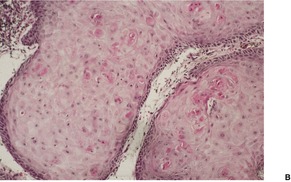

There is prominent hyperkeratosis, often focal parakeratosis, and marked irregular acanthosis that often is of pseudoepitheliomatous proportions (Fig. 31.4). Sometimes the hyperplasia is more regular and vaguely psoriasiform in type. There may be pinpoint ulceration from excoriation. Mitoses are usually increased among the keratinocytes. A hair follicle is often present in the center of each acanthotic downgrowth (Fig. 31.5). 182

Prurigo nodularis. There is marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. (H & E)

Prurigo nodularis. There is focal excoriation and bulbous rete pegs. (H & E)

The upper dermis shows an increase in small blood vessels, and there is often an increase in the numbers of dermal fibroblasts, some of which may be stellate. There are usually fine collagen bundles in a vertical orientation in the papillary dermis. The arrectores pilorum muscles may be prominent. A syringomatous proliferation of eccrine sweat ducts is a rare finding. 183 The inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis is usually only mild and includes lymphocytes, mast cells, histiocytes, and sometimes eosinophils. Extracellular deposition of eosinophil granule protein is usually present. 184 Epidermal mast cells and Merkel cells may be seen.181. and 185. The mast cells are increased in size and become more dendritic. 186 They are seen in close vicinity to nerves which functionally express increased amounts of nerve growth factor receptor (NGFr). 186

Hypertrophy and proliferation of dermal nerve fibers has been emphasized by most,187.188.189. and 190. but it was not a prominent feature in two large series of cases.181. and 191. Small neuroid nodules with numerous Schwann cells have been reported in the dermis.192. and 193. Immunohistochemistry has revealed that calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is expressed in increased amounts in nerve fibers in prurigo nodularis; this may be of significance in the recruitment of eosinophils and mast cells into lesional tissue. 194 The CD10 preparation shows an onion skin-like cuff of positively staining dermal cells surrounding the hyperplastic downgrowths of epidermis. 195

Acanthomas are benign tumors of epidermal keratinocytes. 197 The proliferating cells may show normal epidermoid keratinization or a wide range of aberrant keratinization, including epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (epidermolytic acanthoma), dyskeratosis with acantholysis (warty dyskeratoma), or acantholysis alone (acantholytic acanthoma). 197 These abnormal forms of keratinization occur in a much broader context and have already been discussed in Chapter 9 (pp. 264–267). Brief mention of these forms of acanthoma is made again for completeness. Keratoacanthomas (see p. 702) are not usually considered in this category, although there is no logical reason for their exclusion. The following acanthomas are discussed below:

• epidermolytic acanthoma

• warty dyskeratoma

• acantholytic acanthoma

• seborrheic keratosis

• dermatosis papulosa nigra

• melanoacanthoma

• clear cell acanthoma

• clear cell papulosis

• large cell acanthoma.

Epidermolytic acanthoma is an uncommon lesion which may be solitary, resembling a wart, or multiple. It shows the histopathological changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis and is therefore considered in Chapter 9 with other lesions showing this disorder of epidermal maturation and keratinization (see p. 265).

Warty dyskeratomas are rare, usually solitary, papulonodular lesions with a predilection for the head and neck of middle-aged and elderly individuals (see p. 271). They show suprabasilar clefting, with numerous acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells within the cleft and an overlying keratinous plug.

Acantholytic acanthoma is a solitary tumor with a predilection for the trunk of older individuals.198. and 199. It usually presents as an asymptomatic keratotic papule or nodule. Uncommonly it may resemble a molluscum contagiosum clinically. 200 Multiple lesions have been reported in a renal transplant recipient. 201

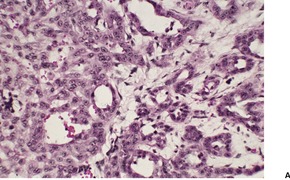

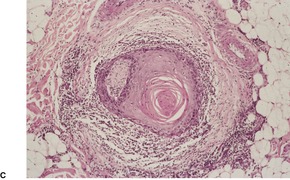

The features include variable hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis and acanthosis, together with prominent acantholysis, most often involving multiple levels of the epidermis (Fig. 31.6). There is sometimes suprabasilar or subcorneal cleft formation, but there is no dyskeratosis. The pattern resembles that seen in pemphigus or Hailey–Hailey disease, but there has been no evidence of these diseases in the cases reported.

(A), (B) Acantholytic acanthoma. Acantholysis involves the lower layers of the hyperplastic epidermis. There is a thick, orthokeratotic stratum corneum. (H & E)

Seborrheic keratoses (senile warts, basal cell papillomas) are common, often multiple, benign tumors which usually first appear in middle life.202. and 203. They may occur on any part of the body except the palms and soles, although there is a predilection for the chest, interscapular region, waistline, and forehead. Seborrheic keratoses are sharply demarcated gray-brown to black lesions, which are slightly raised. They may be covered with greasy scales. Most lesions are no more than a centimeter or so in diameter, but larger variants, sometimes even pedunculated, have been reported.204.205. and 206. A flat plaque-like form is sometimes found on the buttocks or thighs. This should not be confused with the lightly pigmented plaques of unwashed skin which have variously been called keratoderma simplex, 207 dermatitis artefacta, and ‘terra firma-forme’ dermatosis (see p. 299). Rarely it arises in a nevus sebaceus. 208

Rare clinical variants include a familial form, which may be of early or late onset,209.210. and 211. and a halo variant with a depigmented halo around each lesion. 212 The Meyerson phenomenon (eczematous halo) may rarely involve a seborrheic keratosis. 213 Multiple seborrheic keratoses may sometimes assume a patterned arrangement along lines of cleavage214 or a linear (‘raindrop’) pattern. 215 A keratin horn is sometimes present, particularly in the elderly. 216 The eruptive form associated with internal cancer (sign of Leser and Trélat) is discussed below. Inflammation has developed in seborrheic keratoses after docetaxel treatment. 217

The nature of seborrheic keratoses is still disputed. A follicular origin has been proposed. They have also been regarded as a late-onset nevoid disturbance, or the result of a local arrest of maturation of keratinocytes. 218 Of interest is the recent finding of somatic mutations in fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3) in a subset of patients with adenoid and flat seborrheic keratoses.219. and 220. Increased age appears to be a risk factor for these mutations. Furthermore, their preferential occurrence in seborrheic keratoses of the head and neck suggests a causative role for cumulative lifetime ultraviolet light exposure. 220 Mutations in FGFR3 are also found in epidermal nevi and acanthosis nigricans. Somatic mutations in PIK3CA have also been reported. 211 Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been detected in a small number of cases, 221 particularly from the genital region. 222 It has also been found in the seborrheic keratoses of patients who have epidermodysplasia verruciformis.223. and 224. The DNA of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomaviruses has been detected in non-genital seborrheic keratoses. 225 Several cases of necrotizing herpesvirus infection complicating a seborrheic keratosis have been reported. 226 Endothelin-1, a keratinocyte-derived cytokine with a stimulatory effect on melanocytes, is thought to be involved in the melanization of seborrheic keratoses.227. and 228. The basosquamous cell acanthoma of Lund, the inverted follicular keratosis, and the stucco keratosis have all been regarded, at some time, as variants of seborrheic keratosis.197. and 229.

Dermoscopy is a reliable method of distinguishing these lesions from malignant melanoma and other pigmented lesions. The classic criteria – milia-like cysts and comedo-like openings – have a high prevalence but other features such as fissures, hairpin blood vessels, sharp demarcation, moth-eaten borders, and ‘fat fingers’ may also be present.230. and 231.

A case can be made for submitting all suspected seborrheic keratoses for histological examination as clinical misdiagnosis can occur.232. and 233.

Shave excision, curette and cautery, and cryotherapy have all been used to treat seborrheic keratoses. In Australia, excision is sometimes used but there is no Medicare reimbursement for such excisions. Tazarotene cream 0.1% was found to be cosmetically acceptable in a trial comparing cryosurgery, tazarotene, topical imiquimod, and topical calcipotriene. 234

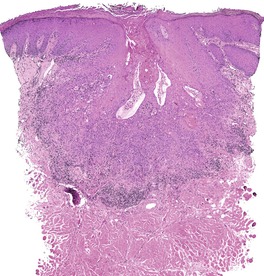

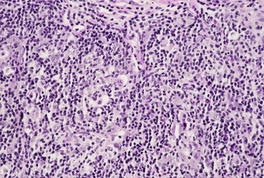

Seborrheic keratoses are sharply defined tumors which may be endophytic or exophytic. 235 They are composed of basaloid cells with a varying admixture of squamoid cells. Keratin-filled invaginations and small cysts (horn cysts) are a characteristic feature. Nests of squamous cells (squamous eddies) may be present, particularly in the irritated type. The squamous eddies of irritated seborrheic keratoses are anatomically related to acrotrichia. 236 Approximately one-third of seborrheic keratoses appear hyperpigmented in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections. 205

At least nine distinct histological patterns have been recognized: acanthotic (solid), reticulated (adenoid), hyperkeratotic (papillomatous), clonal, irritated, inflamed, desmoplastic, adamantinoid, and with pseudorosettes.235.237. and 238. Overlapping features are quite common. The acanthotic type is composed of broad columns or sheets of basaloid cells with intervening horn cysts. The reticulated (adenoid) type has interlacing thin strands of basaloid cells, often pigmented, enclosing small horn cysts (Fig. 31.7). This variant often evolves from a solar lentigo. 235 The hyperkeratotic type is exophytic, with varying degrees of hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Fig. 31.8). There are both basaloid and squamous cells. Clonal seborrheic keratoses (Fig. 31.9) have intraepidermal nests of basaloid cells resembling the Borst–Jadassohn phenomenon (see p. 682). 239 In the irritated variant there is a heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate, with lichenoid features, in the upper dermis. Apoptotic cells are present in the base of the lesion and in areas of squamous differentiation. 240 This represents the attempted immunological regression of a seborrheic keratosis.241. and 242. The term lichenoid seborrheic keratosis is a preferable term to irritated seborrheic keratosis. Kamino bodies (see p. 721) are rarely found in this type. 243 Sometimes there is a heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate without lichenoid qualities; 244 rarely neutrophils are abundant in the infiltrate. 205 This may be regarded as a true inflammatory variant, although often lesions with features overlapping with those of the irritated (lichenoid) type are found. 244 In the desmoplastic variant there are irregular squamous nests and cords of cells extending into a desmoplastic stroma. The trapped cells may mimic a squamous cell carcinoma. 237 This variant is analogous to the desmoplastic tricholemmoma. A variant with intercellular mucin and small basaloid keratinoyctes with spindled cytoplasm has been called an adamantinoid seborrheic keratosis. 238 In the variant with pseudorosettes, basaloid cells are radially arranged around central, small empty spaces. The lesion is acanthotic with occasional horn cysts. 238

Reticulated (adenoid) seborrheic keratosis. There are irregular, acanthotic downgrowths. (H & E)

Seborrheic keratosis of hyperkeratotic type with marked papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis. (H & E)

Clonal seborrheic keratosis. Nests of keratinocytes show the Borst–Jadassohn phenomenon. (H & E)

Tricholemmal differentiation with glycogen-rich cells is an uncommon, usually focal, change.245. and 246. So too is sebaceous differentiation. 247 Acantholysis is another uncommon histological feature.248. and 249. Basal clear cells are sometimes present in seborrheic keratoses. These cells express keratin markers, often at the periphery of the cells, but not S100 or melan-A. They may mimic melanoma in situ on H & E sections. 250 Trichostasis spinulosa with multiple retained hair shafts has also been reported. 251 Amyloid in the underlying dermis is another incidental finding. 235 A verruciform xanthoma-like lesion has also developed in a seborrheic keratosis. 252

The development of a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma or a keratoacanthoma in a seborrheic keratosis is a rare event.253.254.255.256.257.258.259.260. and 261. More common is the juxtaposition or ‘collision’ of these lesions.262. and 263. Another finding is epidermal atypia of varying severity in the cells of a seborrheic keratosis; a progressive transformation to in-situ squamous cell carcinoma (bowenoid transformation) may occur.264.265.266.267.268.269.270. and 271. Rarely, a malignant melanoma may develop in a seborrheic keratosis.260. and 272. In a recent study of 639 consecutive seborrheic keratoses, an associated (adjacent to or contiguous with) lesion was present in 85 cases (9%). 261

The sign of Leser and Trélat is defined as the sudden increase in the number and size of seborrheic keratoses associated with an internal cancer.276.277. and 278. Approximately 100 such cases have been reported,279.280.281. and 282. although some of them are poorly documented as genuine examples of the sign.283. and 284. Other cutaneous paraneoplastic conditions, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertrichosis lanuginosa, and acquired ichthyosis, are sometimes present as well.285.286.287. and 288. Pruritus is also common. 279 A gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinoma is the most frequent accompanying cancer,289. and 290. followed by lymphoproliferative disorders.291.292.293. and 294. The various cancers reported with this sign are analyzed in several reviews and case reports.280.286.287. and 295. Metastases are frequently present and most patients have a poor prognosis.285. and 287.

The seborrheic keratoses may precede, 296 follow, or develop concurrently with the onset of symptoms of the cancer.287. and 297. Cases purporting to represent chemotherapy-induced lesions have been reported. 298 Involution of the seborrheic keratoses has followed treatment of the cancer. The sign has also occurred during the course of the disease. 299 The lesions are most frequent on the trunk. A variant in which they were linear in distribution has been reported. 300

The mechanism responsible for the appearance of these keratoses is not known. Epidermal growth factor does not appear to be increased, 290 although the structurally related α-transforming growth factor was increased in one report. 280 Elevated insulin-like growth factor was present in a patient with eruptive seborrheic keratoses and solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. 301

Eruptive seborrheic keratoses have rarely been reported during the course of an erythrodermic condition.302. and 303. Transient, eruptive seborrheic keratoses have developed in patients with erythrodermic pityriasis rubra pilaris, 304 erythrodermic psoriasis, and an erythrodermic drug eruption. 305 They have also been reported in a patient with acromegaly, 306 in one with HIV infection, 307 and also in a heart transplant recipient. 308

Histological examination of the skin lesions has only been made in isolated cases. 309 In some reports typical seborrheic keratoses have been present. In other instances non-specific hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis without acanthosis have been noted. 287 Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis has also been described. 310 The regression of lesions following treatment of the underlying cancer appears to be associated with a mononuclear cell infiltrate in the upper dermis and lower epidermis. 303

Although regarded by some as a variant of seborrheic keratosis, 205 dermatosis papulosa nigra is a clinically distinctive entity, found almost exclusively in black adults, with a female preponderance. 311 A familial predisposition is often present. 312 There are multiple small pigmented papules, with a predilection for the malar area of the face. The neck and upper part of the trunk may also be involved. Lesions have been found in from 10% to 35% of the black population in the United States. 313 An eruptive form has been reported in association with an adenocarcinoma of the colon. 314

Electrodesiccation is the treatment of choice, particularly if multiple lesions are present. 312

Dermatosis papulosa nigra is characterized by hyperkeratosis, elongated and interconnected rete ridges, and hyperpigmentation of the basal layer (Fig. 31.10). There are often keratin-filled invaginations of the epidermis. The picture is similar to that of the reticulate type of seborrheic keratosis. In contrast to seborrheic keratoses, the epithelial proliferation in dermatosis papulosa nigra is not usually composed of basaloid cells.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra. There are interconnected rete pegs and hyperpigmentation of the basal layer. (H & E)

The term ‘melanoacanthoma’ was introduced in 1960 for a rare benign pigmented lesion which is composed of both melanocytes and keratinocytes. 315 The lesion is a slowly growing, usually solitary, tumor of the head and neck, or trunk, of older people.316.317. and 318. Clinically, a melanoacanthoma resembles a seborrheic keratosis or a melanoma, and may grow to 3 cm or more in diameter. 319 It is best regarded as a variant of seborrheic keratosis. Melanoacanthoma has been recorded as arising from mucous membranes: such lesions represent an unrelated disorder.320.321. and 322.

There is some resemblance to a seborrheic keratosis, with an acanthotic, slightly verrucous epidermis composed of both basaloid and spinous cells. 323 The basaloid cells sometimes form islands, whereas the spinous cells form foci with central keratinization and horn pearl formation (endokeratinization). Numerous dendritic melanocytes are scattered throughout the lesion. 316 The melanocytes contain mature melanosomes and are heavily pigmented. The neighboring keratinocytes are only sparsely pigmented. 324 There is usually pigment in macrophages in the upper dermis. The dendritic melanocytes express S100 protein and HMB-45. 322

Clear cell acanthoma (pale cell acanthoma) is an uncommon firm brown-red dome-shaped nodule or papule, 5–10 mm or more in diameter, with a predilection for the lower part of the legs of middle-aged and elderly individuals.325.326.327.328. and 329. Giant forms have been described.330. and 331. Rarely, other sites have been involved;332.333. and 334. onset in younger patients has also been recorded. 335 Although usually solitary, multiple tumors have been described and a few patients with multiple clear cell acanthomas have also had varicose veins and/or ichthyosis.336.337.338.339. and 340. In one case, the lesion developed over a melanocytic nevus. 341 Associated conditions, both adjacent to and underlying a clear cell acanthoma, are common. 342 The lesions may have a crusted surface and may bleed with minor trauma. A scaly collarette and vascular puncta on the surface of the lesion are common.325.343. and 344. Growth is slow and the tumor may persist for many years. Spontaneous involution has been reported. 345

The exact nosological position of this lesion is uncertain, but it has generally been considered to be a benign epidermal neoplasm (as originally proposed by Degos) rather than a reactive hyperplasia of inflammatory origin.332. and 346. It does not show tricholemmal differentiation. 342 However, the expression of cytokeratins is similar to that seen in some inflammatory dermatoses. 347 Furthermore, clear cell acanthoma has developed in a psoriatic plaque. 348

On dermoscopy, there is some resemblance to psoriasis, with a squamous surface and translucid collarette. 349 There are dilated capillary loops, with a mainly perpendicular orientation to the skin surface. 349

Clear cell acanthomas may be treated with excision, shave excision, cryotherapy, and curettage and electrofulguration. 334 Cryotherapy usually requires three to four courses. As many cases are misdiagnosed clinically as basal cell carcinomas, they are often surgically removed.

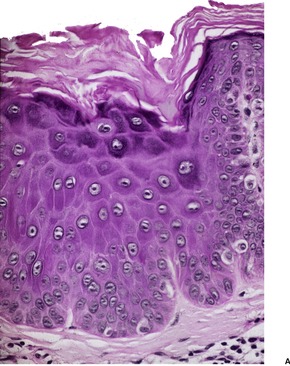

Histological examination shows a well-demarcated area of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia in which the keratinocytes have pale-staining cytoplasm. The epithelium of the adnexa is spared. There are intermittent broad and slender rete pegs, and a tendency for the acanthosis to be more prominent centrally. There may be fusion of the acanthotic downgrowths. Usually there is slight acanthosis of the epidermis, involving one or two rete ridges bordering the area of pale acanthosis (Fig. 31.11). 350

(A) Clear cell acanthoma. (B) The lesion is acanthotic, with pale-staining keratinocytes, except at the periphery of the lesion where they appear normal. (H & E) (C) The cells stain with the PAS stain.

Other epidermal changes include mild spongiosis, exocytosis of neutrophils which may form tiny intraepidermal microabscesses, and thinning of the suprapapillary plates. The epidermal surface shows parakeratotic scale and sometimes focal pustulation. The cytoplasm of the basal cells may not be as pale as that of the other keratinocytes: it is often devoid of melanin pigment, although melanocytes are present. 351 A pigmented variant with dendritic melanocytes has been reported. 352 Cellular atypia is a rare occurrence. 353

The dermal papillae are edematous, with increased vascularity and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate which includes a variable proportion of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. In several cases the sweat ducts have been dilated, and rarely they may be hyperplastic.

A PAS stain, with and without diastase, will confirm the presence of abundant glycogen in the pale cells. Electron microscopy has also confirmed that the keratinocytes contain glycogen.354. and 355. Langerhans cells are also abundant.338. and 356. Immunohistochemistry shows that the cells contain keratin and involucrin, but not carcinoembryonic antigen. 357

It has been suggested that there is a distinct tissue reaction, pale cell acanthosis (clear cell acanthosis), characterized by the presence of pale cells in an acanthotic epidermis. 358 This histological pattern can be seen not only in clear cell acanthoma but also in some seborrheic keratoses, usually the clonal subtype, and rarely in verruca vulgaris. The lesion reported as a cystic clear cell acanthoma may represent this tissue reaction occurring in an epidermal cyst or dilated follicle. 359

Clear cell papulosis is an exceedingly rare condition characterized by multiple white papules on the face, chest, abdomen, or lumbar region of young women and boys.360.361.362.363.364. and 365. There is a predisposition for persons of Asian or Hispanic descent. 366 Some lesions may develop along the ‘milk lines’. The lesions measure 2–10 mm in size. The number of lesions has ranged from 5 to more than 100. It has been suggested that there may be some histogenetic relationship with Toker’s clear cells of the nipple and that cases reported away from the ‘milk lines’ may be a different entity. 367

There is no known treatment. 365

The epidermis is mildly acanthotic with a slightly disorganized arrangement of the epidermal cells. The characteristic feature is the presence of clear cells scattered mainly among the basal cells, with a few cells in the malpighian layer. The cells are larger than the adjacent keratinocytes. The clear cells are variably stained by the PAS, mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and colloidal iron methods. A characteristic feature is the positive immunostaining for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP). 360 They also stain positively for cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), but they are negative for CD1a and S100 protein.366. and 368.

The clear cells in pagetoid dyskeratosis, an incidental histological finding in a variety of lesions, are found at a higher level in the epidermis (see p. 272). They do not stain with the PAS or mucicarmine methods.

Large cell acanthoma occurs as a sharply demarcated, scaly, often lightly pigmented patch, approximately 3–10 mm in diameter, on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged and elderly individuals.369.370. and 371. It is usually solitary. Clinically, it resembles a seborrheic or actinic keratosis. Large cell acanthoma is thought to comprise sunlight-induced clones of abnormal cells, without a tendency to malignancy.369. and 372. However, the author has seen several cases with bowenoid transformation (see below). As such it is a distinctive condition373.374. and 375. and not a variant of solar lentigo, as proposed by Roewert and Ackerman, 376 and others. 377 Human papillomavirus type 6 (HPV-6) has been isolated from lesional skin in a patient with multiple large cell acanthomas. 378

There is epidermal thickening caused by the enlargement of keratinocytes to about twice their normal size (Fig. 31.12). There is also a proportional increase in nuclear size. The lesions are sharply demarcated from the adjacent normal keratinocytes; the adnexal epithelium within a lesion is usually spared. Other features include orthokeratosis, a prominent granular layer, mild papillomatosis, mild basal pigmentation, and some downward budding of the rete ridges. 375 Occasionally there is a focal lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate. Atypia may develop in large cell acanthoma; only rarely is this bowenoid.

Large cell acanthoma. (A) The keratinocytes are larger than usual and the granular layer is thickened. Normal epidermis is present at the edge of the photograph. (B) There is mild basal cell atypia. There would be parakeratosis overlying a solar keratosis. There is orthokeratosis here. (H & E)

The epidermal dysplasias have the potential for malignant transformation. This group includes actinic (solar) keratosis, actinic cheilitis, arsenical keratoses, and PUVA keratosis.

Actinic (solar) keratoses present clinically as circumscribed scaly erythematous lesions, usually less than 1 cm in diameter, on the sun-exposed skin of older individuals.379.380.381. and 382. The face, ears, scalp, hands, and forearms are sites of predilection. 383 In sunbed users, punctate dysplastic keratoses have developed, predominantly on the plantar aspect of the feet. 384 In Australia, actinic keratoses are found in 40–60% of people aged 40 years and over.385. and 386. They develop most often in those with a fair complexion, who do not tan readily. 387 They may also develop in lesions of vitiligo. 388 In contrast, in England the prevalence of actinic keratoses is approximately 15% for men and 6% for women. 389 The prevalence is also low in Italy and Japan. 390

Actinic keratoses may remit, or remain unchanged for many years.391.392.393. and 394. It has been stated that 8–20% gradually transform into squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated.379.395. and 396. The hyperplastic variant appears to have a relatively high rate of malignant transformation. 397 In one study the annual incidence rate of malignant transformation of a solar keratosis was less than 0.25% for each keratosis, 398 but this study has been criticized on several grounds.399. and 400. Patients with solar keratoses on the trunk or lower extremities are at high risk for skin cancer development. 401

Ackerman and others have proposed that actinic keratoses are morphological expressions of squamous cell carcinoma (see p. 693),402.403.404. and 405. while Cockerell has suggested that actinic (solar) keratoses be renamed ‘keratinocytic intraepidermal neoplasia’ or ‘solar keratotic intraepidermal SCC’.406. and 407. It is difficult to envisage clinicians embracing this latter terminology. This trend to abandon precursor diagnoses in favor of the worst scenario outcome has important implications for patient management and their peace of mind, not to mention its conflict with traditional views of the stepwise (multistage) progression of neoplasia.408.409.410.411.412. and 413. Recent work (2008) suggests that Bowen’s disease and actinic keratoses are derived from different cells. Basal cells appear to play a role in the histogenesis of actinic keratosis but not Bowen’s disease. 414

Several clinical variants of actinic keratosis have been described. In the hyperplastic (hypertrophic) form, found almost exclusively on the dorsum of the hands and the forearms, individual lesions are quite thick.415. and 416. The changes probably result in part from the superadded changes caused by rubbing and scratching. They may be overdiagnosed clinically as squamous cell carcinoma. 415 The acantholytic variant clinically mimics a basal cell carcinoma. It is sometimes present in lesions not responding to local therapy but whether it is the cause of the treatment failure or the result of treatment is speculative. The spreading pigmented actinic keratosis is a brown patch or plaque, usually greater than 1 cm in diameter, that tends to spread centrifugally.417. and 418. Some cases appear to represent the collision of an actinic keratosis and solar lentigo. 419 The cheeks and forehead are sites of predilection. Dermoscopy of the pigmented actinic keratosis has a striking similarity to lentigo maligna.420. and 421. The lichenoid actinic keratosis (not to be confused with the lichen planus-like keratosis) is not usually distinctive, although sometimes local irritation is noted. 422

Cumulative exposure to sunlight appears to be important in the etiology. Intermittent, intense ultraviolet (UV) exposure in childhood, manifest as sunburn, is also strongly associated with the prevalence of actinic keratoses. 423 It has been regarded as an ‘occupational and environmental disorder’. 424 Despite educational programs, a significant number of individuals still experience sunburns. 425 It remains to be seen whether the use of sunless tanning products will result in safer sun protection strategies. 426 Recent work has demonstrated that Betapapillomavirus infection in combination with key risk factors increases the risk of actinic keratoses. 389 These viruses were previously categorized as epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) – HPV types. Abnormalities in DNA synthesis in keratinocytes in the skin around the lesion suggest that there is a gradual stepwise progression from sun-damaged epidermis to clinically obvious keratoses, and eventually to squamous cell carcinoma.427. and 428. This occurs at both the morphological and molecular level. 429 The long-term use of hydroxyurea can also produce squamous dysplasia which may be a precursor of multiple squamous cell carcinomas. 430 The keratinocytes in solar keratoses, like those in squamous cell carcinomas, lose various surface carbohydrates. 431

Approximately 50% of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas show overexpression of cyclin D protein as well as p53 positivity.432.433.434.435.436. and 437. Bcl-2 may be increased in actinic keratoses. 438 The presence of these regulatory markers correlates with the severity of the solar elastosis, suggesting that the grade of solar elastosis is a helpful marker of epithelial UV damage. 439 Tenascin expression is increased in the stroma beneath actinic keratoses and this increases with the atypia. 440 Activated ras genes are found in a small percentage of cases. 441 There is also diminished expression of tumor suppressor genes. 442 However, no genetic susceptibility to actinic keratoses has been found. 436

Treatment guidelines, prepared on behalf of the British Association of Dermatologists, were published in 2007. They are, where possible, evidence based. They are too complex to summarize here as the preferred therapy differs, based on the number of lesions, the type of lesions, response to previous therapies, the location of the lesions, and characteristics of the patient. 443 The therapies listed include cryosurgery,444. and 445. 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac, imiquimod (not licensed for this purpose in some countries), resiquimod, 446 curettage, and photodynamic therapy. 443 Some patients show adverse reactions to diclofenac. 447 Plastic surgeons are more likely to use excisional biopsies and dermatologists shave biopsies to make the diagnosis of actinic keratosis. 448 Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is effective in up to 91% of actinic keratoses in trials comparing it with cryotherapy. Although more expensive, it is particularly useful when multiple keratoses are present.443.449. and 450. However, a randomized trial published just recently found PDT to have inferior efficacy for treatment of multiple actinic keratoses on the extremities when compared with cryotherapy. 451 Stabbing headaches are experienced by some patients receiving cryotherapy for lesions on the face. 452 Another trial has found that continuous activation of porphyrins by daylight is as effective as conventional PDT. 453 Photodynamic therapy results in apoptosis of atypical keratinocytes. 454 Imiquimod cream 5% is another effective treatment,455.456.457. and 458. but the duration of treatment required sometimes results in poor patient compliance. Imiquimod stimulates a cutaneous immune response characterized by increases in activated dendritic cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. 456 It also favorably influences the expression of genes in actinic keratoses, 459 but squamous cell carcinoma may still arise subsequently in a treatment site.460. and 461. Resiquimod, which is more potent than imiquimod, is still undergoing evaluation. 446 Other treatment reviews have been published.382. and 462.

Long-term treatment of photoaged human skin with topical retinoic acid improves epidermal cell atypia, consistent with its ability to act as a chemopreventive agent in epithelial carcinogenesis.463. and 464. It also thickens the collagen band in the papillary dermis. 464 Facial resurfacing using the carbon dioxide laser, a 30% trichloroacetic acid peel, or 5% fluorouracil cream have been shown to reduce the subsequent development of actinic keratoses and skin cancers compared with a control group. 465

Little has been written on the recurrence rate of actinic keratoses following biopsy with incomplete margins. In one recently published study, of 85 incompletely removed actinic keratoses not subjected to further treatment, 48.2% recurred. All recurred as actinic keratoses except one case, which recurred as a squamous cell carcinoma. 466

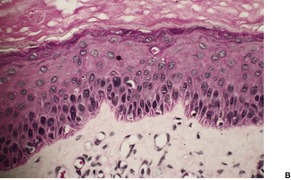

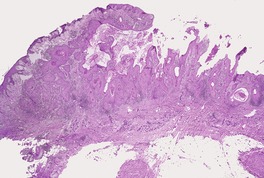

Diagnostic biopsy is undertaken in only a small percentage of actinic keratoses diagnosed clinically. 385 The clinical accuracy in the recognition of actinic keratoses varies from 74 to 94%. 468 The usual actinic keratosis is characterized by focal parakeratosis, with loss of the underlying granular layer and a slightly thickened epidermis with some irregular downward buds (Fig. 31.13). Uncommonly, the epidermis is thinner than normal. In all cases there is variable loss of the normal orderly stratified arrangement of the epidermis; this is associated with cytological atypia of keratinocytes, which varies from slight to extreme. The term ‘bowenoid keratosis’ may be used when the atypia is close to full thickness. 417 This variant differs markedly from the ‘de novo’ form of Bowen’s disease (see below). Sometimes the dysplastic epithelium shows suprabasal cleft formation (see below).379.469. and 470. There is often a sharp slanting border between the normal epidermis of the acrotrichia and acrosyringia and the parakeratotic atypical epithelium of the keratosis. 471 However, dysplastic epithelium may involve the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.471.472. and 473. The parakeratotic scale may sometimes pile up to form a cutaneous horn. 379 Large keratohyaline granules are sometimes present in actinic keratoses. 474

Solar keratosis. There is mild to moderate atypia of keratinocytes and some pallor of cells. There is overlying parakeratosis. (H & E)

Actinic keratoses must be distinguished from the epidermal dysmaturation that may be seen following chemotherapy or transplantation. 475 It is a histological diagnosis characterized by disruption of keratinocyte maturation, loss of polarity, widened intercellular spaces, irregular large nuclei, mid-epidermal mitotic figures, and apoptosis.476. and 477. Colchicine intoxication can also result in dysmaturation with metaphase-arrested keratinocytes and basal vacuolar change. 478

The dermal changes include actinic elastosis, which is usually quite severe, and a variable, but usually mild, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. 379 As mentioned above, the grade of solar elastosis is a marker of epithelial UV damage. 439 Inflammatory keratoses may develop during chemotherapy of malignant disease with fluorouracil and its analogues.479.480.481. and 482. There is vascular telangiectasia and a moderately heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the upper dermis. Inflammation of actinic keratoses has also been reported following therapy with sorafenib, a multitargeted tyrosine-kinase inhibitor. 483 Some actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma with this therapy. 483 An inflammatory response is also present in actinic keratoses before they progress to squamous cell carcinomas, unrelated to any therapies. 484 The inflammation subsides rapidly following this conversion. 484

In the hyperplastic (hypertrophic) form there is prominent orthokeratosis with alternating parakeratosis. 415 The epidermis usually shows irregular psoriasiform hyperplasia, and sometimes there is mild papillomatosis. Dysplastic changes are sometimes minimal and confined to the basal layer. 416 The presence of vertical collagen bundles and some dilated vessels in the papillary dermis is evidence that these lesions represent actinic keratoses, with superimposed changes due to rubbing or scratching (lichen simplex chronicus). 415 Hyperplastic (hypertrophic) forms have a higher resistance to apoptotic stimuli compared to atrophic variants. 485

In the closely-related proliferative variant, there is a strong propensity to transform into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma. 486 Nests of atypical cells extend as finger-like projections into the upper dermis. It has a pseudo-infiltrative appearance. Extension down hair follicles and, less frequently, acrosyringia may be present. A heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes and some plasma cells is often present. 486

In the atrophic actinic keratosis, the epidermis is thin with only several layers of keratinocytes. Atypia is usually limited to the basal layer. There is usually overlying hyperkeratosis and focal parakeratosis.

In the acantholytic variant, there are clefts, usually suprabasal in location, although the change may be more widespread with acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells resulting from anaplastic/atypical changes producing disrupted intercellular bridges. 382

In the pigmented variant there is excess melanin in the lower epidermis, usually in both keratinocytes and melanocytes, but sometimes only in one or the other. 417 Melanophages are usually found in the papillary dermis. 417

The bowenoid actinic keratosis is a controversial entity. It is usually a focal change, indistinguishable from Bowen’s disease. Overlying parakeratosis is often present. The author rarely uses the term these days, and only as a ‘fence-sitting’ diagnosis on 2 mm biopsies (or smaller). The pagetoid variant of actinic keratosis is closely related. 487

In lichenoid actinic keratoses there is a superficial, often band-like, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, with occasional apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer and some basal vacuolar change. 422 The acral keratotic lesions with a lichenoid infiltrate, reported as a possible manifestation of graft-versus-host disease, may have been a manifestation of HPV infection, as wart-virus features sometimes remit in the presence of a lichenoid infiltrate. 488

The lymphomatoid keratosis is mentioned here for completeness although it does not have epidermal atypia or lichenoid (interface) changes. 489 It is an epidermotropic subtype of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia with a dense, band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes beneath a sometimes hyperplastic epidermis. It looks like a lichen planus-like keratosis but with epidermotropism rather than basal cell death. 489

In all types of actinic keratoses in immunosuppressed patients there is usually marked atypia of the keratinocytes; 490 multinucleate forms may be present. 490 Confluent parakeratosis and verruciform changes may also occur.491. and 492.

It is sometimes a matter of personal judgment whether a lesion is considered to show early squamous cell carcinomatous change or not. 493 The protrusion of atypical cells into the reticular dermis and the detachment of individual nests of keratinocytes from the lower layers of the epidermis are criteria used to diagnose invasive transformation. 493 Step sections are important in small biopsies initially regarded as solar keratosis. More significant pathology may emerge in the deeper sections.494. and 495. Despite these difficulties there is a good concordance in the diagnosis of these borderline cases among dermatopathologists. 496 An AgNOR analysis (see p. 723) may identify actinic keratoses with high proliferative activity and an increased tendency to develop into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. 497

Confocal laser microscopic imaging of actinic keratoses has been used. 498 A diagnosis of actinic keratosis can often be made by this technique. 499 Fluorescence techniques are not a suitable method of distinguishing keratinocytic atypias from normal skin. 500

Ultrastructural studies suggest that the hyperpigmentation in the pigmented variant is due to enhanced melanosome formation and distribution, and not to a block in the transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes. 418

Actinic cheilitis (solar cheilosis, actinic keratosis of the lip) is a premalignant condition seen predominantly on the vermilion part of the lower lip. It results from chronic exposure to sunlight, 501 although smoking and chronic irritation may also contribute. 502 There are dry, whitish-gray scaly plaques in which areas of erythema, erosions, and ulceration may develop. 501 The whitish areas were known in the past as leukoplakia. 503 Large areas of the lower lip may be affected. Squamous cell carcinoma may develop after a latent period of 20–30 years,504. and 505. although the incidence of this transformation is difficult to quantify. 502 This transformation appears to be related to dysregulation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT-3), a protein involved in the control of cell proliferation and apoptosis. 506

An acute form of actinic cheilitis, characterized by edema, erythema, and erosions, has been recognized. 503 It is an uncommon response to prolonged exposure to sunlight.

Treatment usually parallels that given for actinic keratoses at other sites and includes cryotherapy, electrosurgery, imiquimod, retinoids, carbon dioxide laser ablation, and surgical excision. 507 Photodynamic therapy has also been used successfully. 507

The lesions show alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis. The epidermis may be hyperplastic or atrophic. Other features are disordered maturation of epidermal cells, increased mitotic activity, and variable cytological atypia. 504 Sometimes foci of severe atypia are found when the entire vermilion is removed even though the biopsy showed milder changes. 509 Squamous cell carcinoma may develop in areas of marked atypia. Cytokeratin expression in actinic cheilitis is not related to the degree of dysplasia. 510

There is prominent solar elastosis of the submucosal connective tissue, some vascular telangiectasia, and a mild to moderate infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells. Plasma cells are usually prominent, particularly beneath areas of ulceration. 508 An intense inflammatory cell infiltrate is often predictive of an adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinoma. 511

Actinic cheilitis and Bowen’s disease both need to be distinguished from pagetoid dyskeratosis, which has been found as an incidental histological feature in over 40% of specimens from the lip. 512 It is composed of large keratinocytes with a condensed nucleus, a clear halo, and abundant pale cytoplasm. 512 This change is not confined to the lips (see p. 272).513. and 514.

For more than a century inorganic arsenic was used in the treatment of many diverse conditions. 515 The recognition of its adverse effects, and its replacement by more effective therapeutic agents, has led to a marked reduction in the incidence of arsenic-related conditions. 516 However, there is a high arsenic content in some drinking waters and naturopathic medicines.517.518.519.520.521.522. and 523. Chronic arsenic poisoning is a worldwide public health problem. 524

The best-known effect of chronic arsenicism is cutaneous pigmentation, which may be diffuse or of ‘raindrop’ type. 525 More than 40% of affected individuals develop keratoses on the palms and soles, and sometimes this is associated with a mild diffuse keratoderma. 525 Hyperkeratosis on the sole is the most sensitive marker for the detection of arsenicism at an early stage. 526 There is an increased incidence of multiple skin cancers, which include Bowen’s disease, basal cell carcinomas, and squamous cell carcinomas.521.527. and 528. The lesions are sometimes quite exophytic in appearance. Visceral cancers, particularly involving the lung and genitourinary system, may also be found. 529

Many arsenical skin cancers express p53, although arsenic-related basal cell carcinomas express it less intensely than sporadic ones. 530 It is also found in perilesional skin.531. and 532. The expression of p53 is reduced after UVB therapy. 533 Arsenic also appears to produce defective expression of β1-integrins in arsenical keratoses. 534

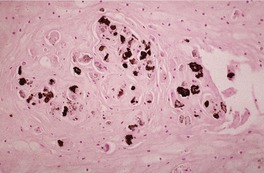

Arsenical keratoses are of the hyperkeratotic type. Sometimes there is prominent hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis, but no atypia. These lesions have a superficial resemblance to the hyperkeratotic type of seborrheic keratosis. Similar lesions follow exposure to tar (Fig. 31.14). 535 In other cases there is mild atypia resembling the hyperkeratotic variant of actinic keratosis.

Tar keratosis. There is pronounced hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis and acanthosis. (H & E)

In some lesions of Bowen’s disease related to exposure to arsenic there may be areas resembling seborrheic keratosis, superficial basal cell carcinoma, or intraepidermal epithelioma of Jadassohn. Invasive carcinomas arising in Bowen’s disease show the non-keratinizing pattern of squamous cell carcinoma, sometimes with areas of appendageal differentiation (see below).

The basal cell carcinomas that develop may be of solid or (multifocal) superficial type.

A PUVA keratosis is a distinctive form of keratosis, often found on non-sun-exposed skin of patients who have received long-term treatment with psoralens and ultraviolet-A radiation (PUVA). 536 It is a raised papule with a broad base and a scaly surface, often with a warty appearance. There is an increased risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer, particularly with long-term, high-dose exposure.537.538. and 539. Punctate keratoses on the hands and feet are a rare complication of PUVA therapy. 540

There is a variable degree of acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and parakeratosis. Papillomatosis is present in one-half of the lesions. PUVA keratoses differ from actinic keratoses by their paucity of atypical cells and an absence of solar elastosis. 536 The lesions reported as disseminated hypopigmented keratoses developed in young patients who had previously received PUVA therapy. 541 They had some histological resemblance to stucco keratoses (see p. 701). 541

Although the term ‘intraepidermal carcinoma’ is often used synonymously with Bowen’s disease, it is used here in a broader sense to include not only carcinoma in situ of the skin (Bowen’s disease), and penis (erythroplasia of Queyrat), but also intraepidermal epithelioma of Jadassohn, a controversial entity of disputed histogenesis. Paget’s disease is sometimes included in this category because of the presence of cytologically malignant cells within the epidermis. Paget’s disease is discussed with the appendageal tumors on page 788.

Bowen’s disease is a clinical expression of squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin. 542 It presents as an asymptomatic well-defined erythematous scaly plaque, which expands centrifugally. Verrucous, nodular, eroded, and pigmented variants occur.543.544.545.546. and 547. Many of the pigmented lesions reported in the anogenital area as Bowen’s disease548.549. and 550. would now be regarded as examples of bowenoid papulosis551 (see p. 625).

Bowen’s disease has a predilection for the sun-exposed areas (particularly the face and legs) of fair-skinned older individuals.552.553. and 554. It is uncommon in black people, 555 in whom it is found more often on areas of the skin that are not exposed to the sun. 556 Its incidence in the Canadian province of Alberta, in the 5-year period from 1996 to 2000, was 22.4 lesions per 100 000 women and 27.8 per 100 000 men. 557 Lesions may also develop on the trunk, 558 and the vulva, and rarely on the nail bed,559.560.561.562.563.564.565. and 566. where it may be polydactylous, 567 lip, 568 nipple, 569 palm,570.571. and 572. sole, 573 web-spaces of the feet, 574 and the margin of an eyelid.575. and 576. In one case Bowen’s disease of the nail bed presented as a longitudinal melanonychia. 577 In another there was periungual Bowen’s disease and vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) concordant for the same HPV types (HPV-34 and HPV-21). 578 Bowen’s disease has been reported in the wall of an epidermoid, and a follicular cyst,579. and 580. in a lesion of porokeratosis of Mibelli, 581 above a scar, 582 in erythema ab igne, 583in a smallpox vaccination scar, 584 and in seborrheic keratoses (see p. 672).

Several investigators have proposed that Bowen’s disease should be considered a skin marker for internal malignant disease,585.586.587.588. and 589. although more recent studies have shown no evidence for this association.590.591. and 592. However, patients with Bowen’s disease have the same increased risk of developing a subsequent skin cancer as do those with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. 593

Invasive carcinoma develops in up to 8% of untreated cases.594. and 595. This complication, which is not well recognized, is characterized by the development of a rapidly growing tumor, 1–15 cm in diameter, in a pre-existing scaly lesion. 595 It appears to be more common in older people, and in immunocompromised patients. 596 Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is a not uncommon complication of the diffuse variant of Bowen’s disease, associated with extensive adnexal extension of the disease. 597 The invasive tumor has metastatic potential, which has been stated to be as high as 13%, 595 although this would appear to be an overestimation of the risk.594.598.599. and 600. Spontaneous complete regression of Bowen’s disease has also been reported. 601

Several factors have been implicated in the etiology of Bowen’s disease. They include prolonged exposure to solar radiation, the ingestion of arsenic,525.585. and 602. and infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV). 603 Whereas HPV type 16 (HPV-16) and HPV-18, and to a lesser extent HPV-18, 31, 33, 39, 52, 67, and 82 have been detected in Bowen’s disease of the genital region and its precursors,604.605. and 606. there are now several reports of non-genital Bowen’s disease related to infections with HPV-2, 607 HPV-16,608.609.610.611. and 612. HPV-27, 613 HPV-33, 613 HPV-34,614. and 615. HPV-56,616. and 617. HPV-58, 618 HPV-59, 619 and HPV-76. 613 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-related HPV types (Betapapillomavirus) are associated with the pathogenesis of Bowen’s disease as well as the better known mucosal strains of HPV. 620 There is a clear association between anal intraepithelial neoplasia and high-risk HPV types in patients with HIV infection.621. and 622. It is an important precursor of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.623. and 624. Bowen’s disease is a rare complication of the treatment of psoriasis with psoralens and ultraviolet-A radiation (PUVA).625.626. and 627. It has been reported in a patient who performed arc welding. 628

Dermoscopy can be helpful for diagnosing Bowen’s disease. It is characterized by glomerular vessels and a scaly surface. 629 In pigmented lesions, small brown globules and/or homogeneous pigmentation are also present. 629

Bowenoid papulosis (see p. 625) consists of one or more indolent, verrucous papules on the genitalia with a clinical resemblance to condyloma acuminatum and a histological resemblance to Bowen’s disease. HPV-16 is the most frequently detected HPV subtype detected in this condition. 630 It usually responds to local therapies, but recurrences and the development of invasive carcinoma have been reported. 605 The term ‘penile intraepithelial neoplasia’ (PIN) has been coined to encompass the three preinvasive clinical entities of penile Bowen’s disease, erythroplasia of Queyrat, and bowenoid papulosis. 631

No single therapeutic option is unequivocally superior to any other and the treatment used often depends on patient preference, cost, the clinical situation, and the clinician’s experience/preference for a particular therapy.632.633.634.635.636.637. and 638. Cryotherapy is most commonly used. Recurrences occur particularly when adnexal structures are involved. Curettage ± cautery gives cure rates of 93–98%. 638 It is also cost effective. 639 Imiquimod cream 5% produces clearance in about 80% of cases.640.641.642.643. and 644. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma has developed in several cases treated with this therapy. 645 Some patients discontinue imiquimod because of a local reaction.

Photodynamic therapy, usually in conjunction with topical 5-aminolevulinic acid, is effective for large or multiple lesions.646. and 647. It has also been used for subungual lesions. 648 Extensive vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) has been treated using photodynamic therapy with meta-tetrahydroxychlorin. 649

Radiation therapy is now used less often. 650 Acitretin has been used to treat multiple arsenical keratoses and Bowen’s disease. 651 Surgery is often used. Recurrence rates are usually less than 5%. 557 A 5-year recurrence rate of 6.3% was obtained in 270 cases treated with Mohs surgery, but the majority of cases were on the head and neck where standard surgery is associated with higher recurrence rates. 652