Figure 29-1 Epidermal nevus. The nevus lies in a fold of the external ear and has a papillary appearance.

Figure 29-2 Linear epidermal nevus. This example is pigmented and lies in the midline, on the back of the neck.

In the systematized type, papillomatous hyperkeratotic papules in a linear configuration are present not just as one linear lesion, as in the localized type, but as many linear lesions. These linear lesions often show a parallel arrangement, particularly on the trunk. They may be limited to one side of the patient or may have a bilateral, symmetric distribution. The term ichthyosis hystrix is occasionally used, perhaps unnecessarily, for instances of extensive bilateral lesions (9).

Localized and, more commonly, systematized linear epidermal nevi may be associated with skeletal deformities and central nervous system deficiencies, such as mental retardation, epilepsy, and neural deafness (10).

The presence of a basal cell epithelioma within a linear epidermal nevus has been observed occasionally, particularly on the head in cases in which the linear epidermal nevus has been associated with either a nevus sebaceous or a syringocystadenoma papilliferum (see Chapter 30) (11). In areas other than the head, it is very rare (12). Similarly, development of an SCC has been described only rarely (13,14), but in one instance the SCC had metastasized to a regional lymph node (15).

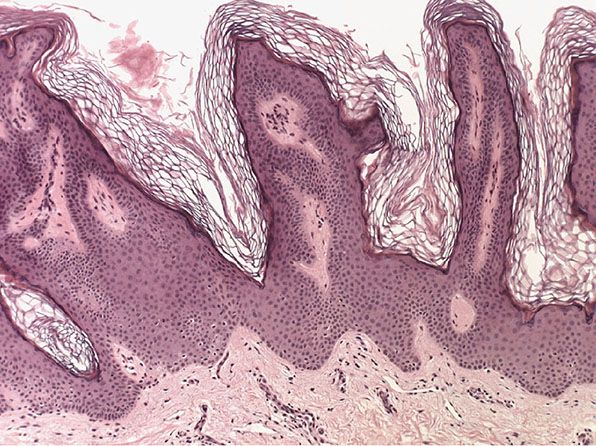

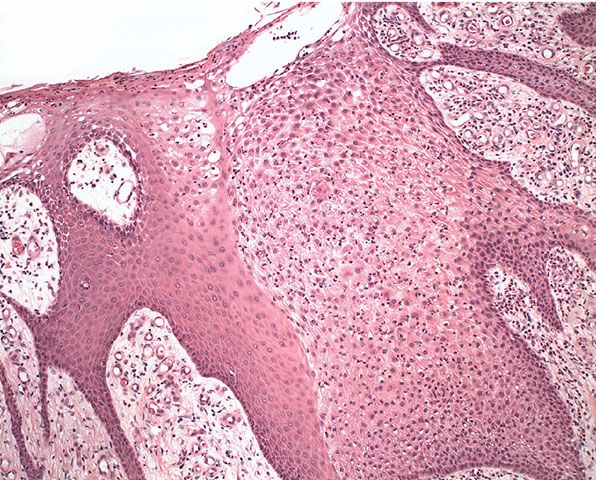

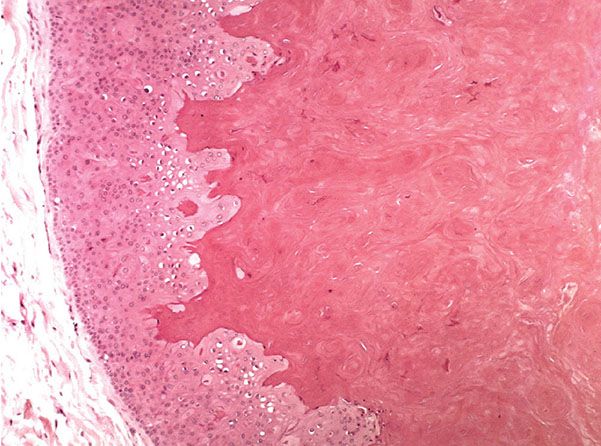

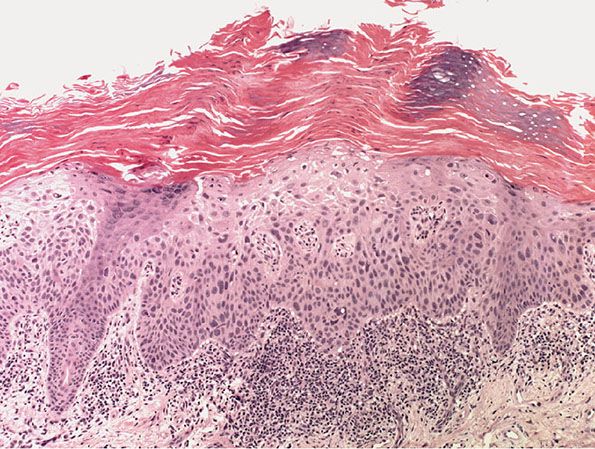

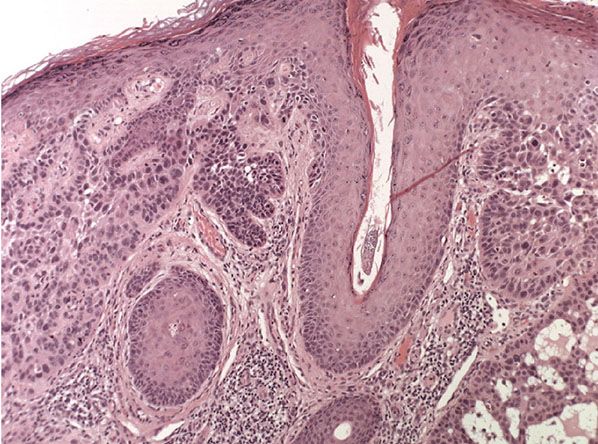

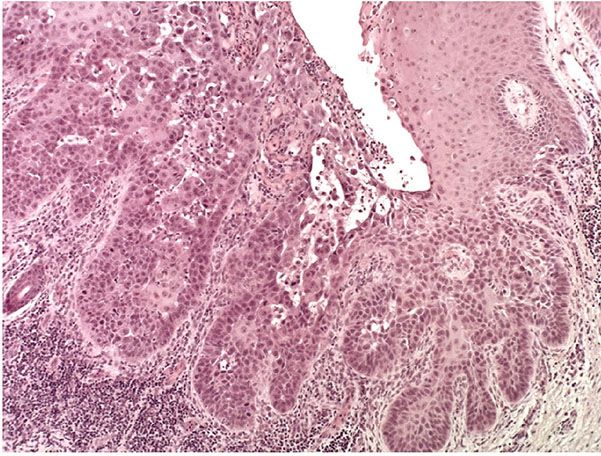

Histopathology. Nearly all cases of the localized type of linear epidermal nevus and some cases of the systematized type show the histologic picture of a benign papilloma (9,16). One observes considerable hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis with elongation of the rete ridges resembling seborrheic keratosis (Fig. 29-3).

Figure 29-3 Epidermal nevus. The nevus shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and flat-topped papillary projections.

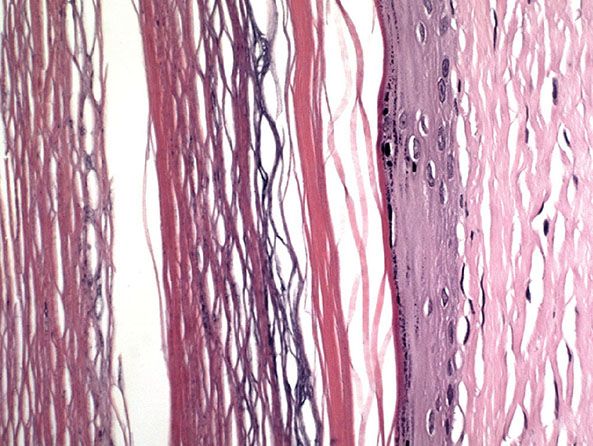

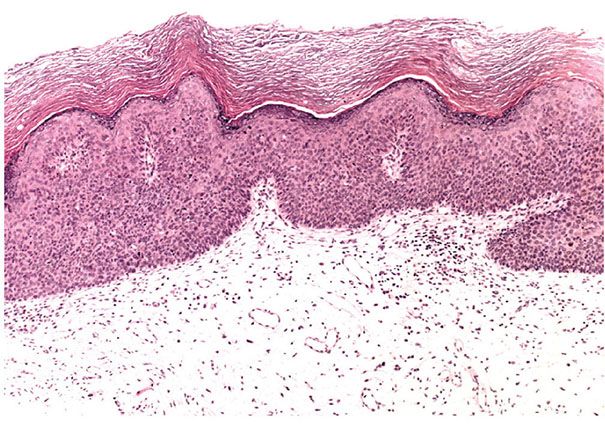

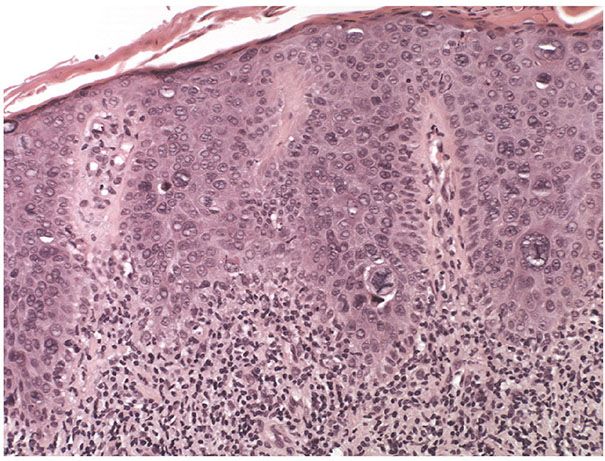

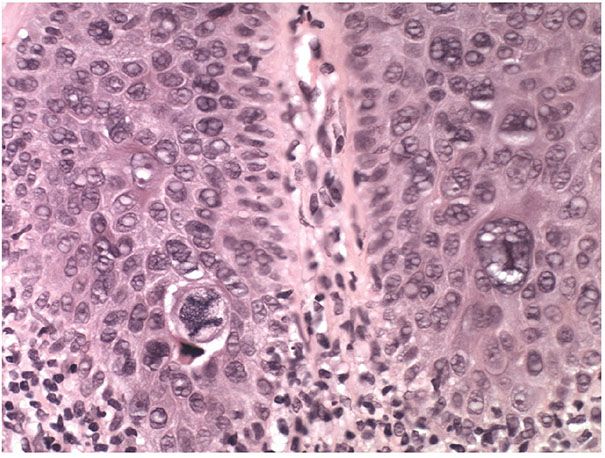

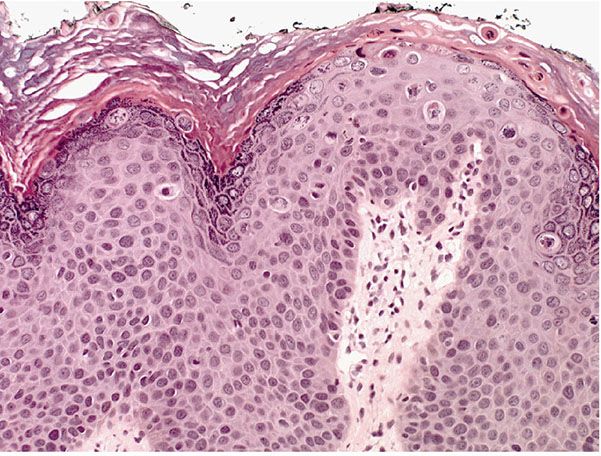

Occasionally in cases of the localized type, but quite frequently in cases of the systematized type, particularly those with a widespread distribution, one observes the rather striking histologic picture referred to either as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (17) or as granular degeneration of the epidermis (18). It is the same process that was first recognized in all cases of bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, a disorder that is often referred to as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (see Chapter 6). It has since been found to occur in several other conditions as well (see Isolated and Disseminated Epidermolytic Acanthoma section).

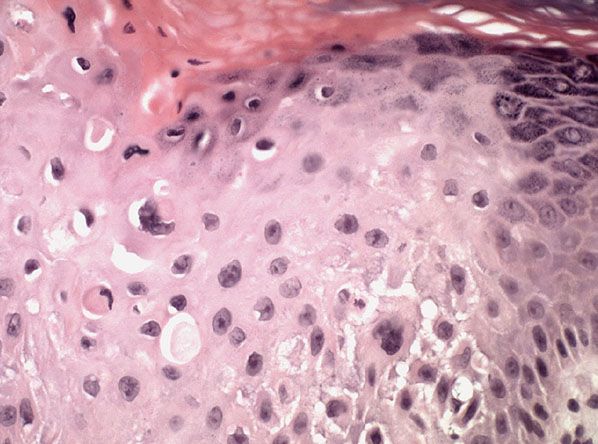

The salient histologic features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis are (a) perinuclear vacuolization of the cells in the stratum spinosum and in the stratum granulosum; (b) irregular cellular boundaries peripheral to the vacuolization; (c) an increased number of irregularly shaped, large keratohyaline granules; and (d) compact hyperkeratosis in the stratum corneum (18,19).

In some instances, histologic examination of unilateral linear lesions reveals features of acantholytic dyskeratosis as seen in Darier disease (see Chapter 6). In some patients, these linear lesions have been present since birth or infancy (20), but in most instances they have arisen in adult life (21). Because acantholytic dyskeratosis is not specific for Darier disease, the proposal has been made to designate such cases not as Darier disease but as acantholytic dyskeratotic epidermal nevus (21).

Differential Diagnosis. The histologic picture of a benign papilloma, as found in most cases of linear epidermal nevus, can also be seen in seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, and acanthosis nigricans. Even though these four conditions have in common hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis, they can be differentiated easily in typical cases; however, one is occasionally unable to make a diagnosis any more specific than benign papilloma, or verrucous keratosis. Thus, in the following three situations, clinical data are required for differentiation from linear epidermal nevus: (a) the hyperkeratotic type of seborrheic keratosis, which is characterized by the absence of basaloid cells and horn cysts and instead shows upward extension of epidermis-lined papillae; (b) old verrucae vulgares, which no longer show vacuolization of epidermal cells or columns of parakeratosis (see Chapter 25); and (c) acanthosis nigricans showing more pronounced acanthosis and greater elongation of the rete ridges than usual (see Chapter 17).

NEVOID HYPERKERATOSIS OF NIPPLE AND AREOLA

Clinical Summary. Nevoid hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis of nipples and areola presents as sharply demarcated papules and plaques, often appearing at puberty or during pregnancy and persisting unchanged. There are no associated systemic or dermatologic conditions. The main differential diagnosis is seborrheic keratosis (22).

Histopathology. There are papillomatous elongations of the epidermis with hyperkeratosis and areas of keratotic plugging (23). This condition represents a nevoid form of hyperkeratosis (24).

NEVUS COMEDONICUS

Clinical Summary. A nevus comedonicus consists of closely set, slightly elevated papules that have in their center a dark, firm, hyperkeratotic plug resembling a comedo. Nevus comedonicus, like linear epidermal nevus, usually has a linear configuration and occurs as a single lesion. In some instances, however, there are multiple bilateral linear lesions (25) or lesions that are randomly distributed rather than linear (26). Lesions may be present on the palms or soles in addition to other areas (27,28). Such cases may represent a combination of nevus comedonicus with a porokeratotic eccrine duct nevus (see the next section).

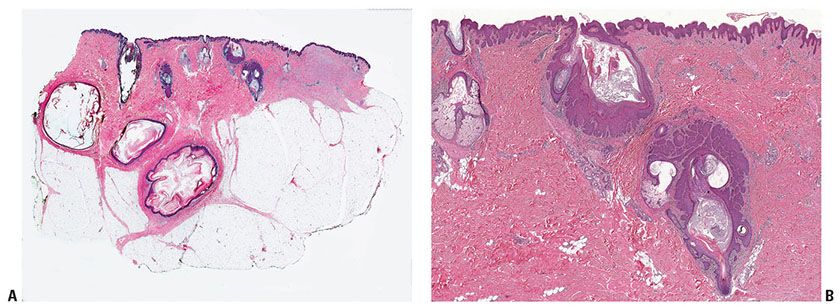

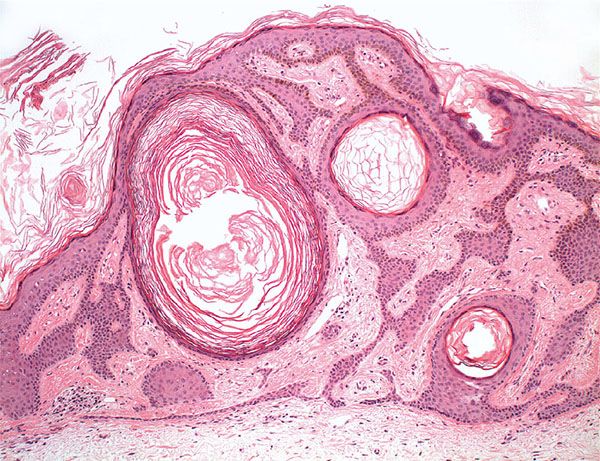

Histopathology. Each comedo is represented by a wide, deep invagination of the epidermis filled with keratin (Fig. 29-4). These invaginations resemble dilated hair follicles; in fact, as evidence that they actually represent rudimentary hair follicles, one occasionally finds in the lower portion of an invagination one or even several hair shafts (25). One or two small sebaceous gland lobules may also be seen opening into the lower pole of invaginations (26).

Figure 29-4 Nevus comedonicus. A: There is a deep invagination of the epidermis containing keratin, and there are several keratinous cysts in the dermis. This is a staged excision of a larger lesion (note scar at right of image). B: Two follicles from near the center of the specimen are dilated and filled with keratin. There is hamartomatous thickening of the epithelium of these follicles, and dermal papillae are elongated in the overlying epidermis.

In several instances, the keratinocytes composing the follicular epithelial wall have shown the typical changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (see the following section) (29), indicative of a relationship of nevus comedonicus to systematized nevus verrucosus (see Chapter 30).

POROKERATOTIC ECCRINE OSTIAL AND DERMAL DUCT NEVUS

Clinical Summary. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus may be limited to a palm (30) or to a sole (31) but may be present on both hands and feet and elsewhere (32,33). It may involve not only eccrine ducts, but also hair follicles on the hairy parts of the body (34).

Histopathology. In the porokeratotic eccrine duct nevus, each invagination consists of a dilated eccrine duct containing a parakeratotic plug. The absence of the granular layer at the base of the plug together with the presence of keratinocytes showing vacuolization of their cytoplasm results in a histologic picture resembling that of porokeratosis (see Chapter 6) (30–32).

ISOLATED AND DISSEMINATED EPIDERMOLYTIC ACANTHOMA

Clinical Summary. Isolated epidermolytic acanthoma, histologically characterized by the presence of “epidermolytic hyperkeratosis,” does not have a characteristic clinical appearance or location. Usually it occurs as a solitary papillomatous lesion less than 1 cm in diameter (35–38). Occasionally, several lesions are seen in a localized area (38,39). One case has been described that was probably secondary to trauma (40).

Disseminated epidermolytic acanthoma occurs as numerous discrete, flat, brownish papules 2 to 6 mm in diameter resembling seborrheic keratoses. The upper trunk, especially the back, is the site of predilection (41,42).

Histopathology. In addition to hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis, one observes pronounced epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, also referred to as granular degeneration, throughout the stratum malpighii, sparing only the basal layer, just as seen in linear epidermal nevi with epidermolytic changes. One observes both intracellular and intercellular edema of the epidermal cells and keratohyaline granules that are coarser than normal and extend to a greater depth in the stratum malpighii (35).

Differential Diagnosis. Myrmecia warts, caused by human papillomavirus type 1 (HPV-1), also show perinuclear vacuolization and an abundance of keratohyaline granules, representing a type of “granular degeneration” similar to that seen in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. However, in myrmecia warts, the keratohyaline granules are eosinophilic and coalesce in the upper layers of the epidermis to form large, homogeneous, eosinophilic “inclusion bodies.” In verrucae vulgares, usually caused by HPV-2, foci of vacuolated cells and clumped basophilic keratohyaline granules may be present, but these changes are limited to the upper layers of the epidermis. In addition, both myrmecia warts and verrucae vulgares show focal parakeratosis rather than orthokeratosis as seen in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (see Chapter 25).

INCIDENTAL EPIDERMOLYTIC HYPERKERATOSIS

Clinical Summary. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is seen not only in isolated and disseminated epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (see previous section), but also as a regular finding in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, or bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (see Chapter 6), and in epidermolytic keratosis palmaris et plantaris and as an occasional finding in linear epidermal nevus and nevus comedonicus. In addition, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may represent an incidental histologic finding in many different types of lesions, largely but not exclusively tumors. It has also been observed in normal oral mucosa adjacent to lesions of SCC and basal cell epithelioma (43).

Histopathology. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may be seen throughout an entire lesion of solar keratosis (44) and in the entire lining of trichilemmal cyst (45). More commonly, however, the histologic features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis are seen as a small focus, often limited to a single epidermal rete ridge, in such diverse lesions as sebaceous hyperplasia (46), intradermal nevus, hypertrophic scar (47), superficial basal cell epithelioma (48,49), seborrheic keratosis, the margin of an SCC, lichenoid amyloidosis, and granuloma annulare (17). In some instances, the process is limited to one or two intraepidermal sweat duct units (47). It is more frequently seen in dysplastic nevi than in ordinary melanocytic nevi (48).

ISOLATED AND DISSEMINATED ACANTHOLYTIC ACANTHOMA

Clinical Summary. This condition usually occurs as a solitary papule or small nodule (50), although there may be multiple lesions (51,52). No characteristic clinical appearance or location exists, although multiple lesions have been seen largely in the genital region (31,53).

Histopathology. Acantholysis is the most prominent feature. The pattern may resemble that of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus foliaceus, or benign familial pemphigus (50). Acantholysis may be combined with dyskeratosis, in which case the histologic picture resembles that of Darier disease as the result of the presence of corps ronds and grains (17,51,52). Because of this, the alternative name of dyskeratotic acanthoma has been suggested (54).

INCIDENTAL FOCAL ACANTHOLYTIC DYSKERATOSIS

Clinical Summary. Analogous to epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, acantholytic dyskeratosis is seen as a regular histologic feature in Darier disease (see Chapter 6), transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), and warty dyskeratoma. It is also an occasional finding in acantholytic dyskeratotic epidermal nevus, a variant of linear epidermal nevus. In addition, again like epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis is observed occasionally as an incidental histologic finding in a variety of lesions, including vascular nevi (55).

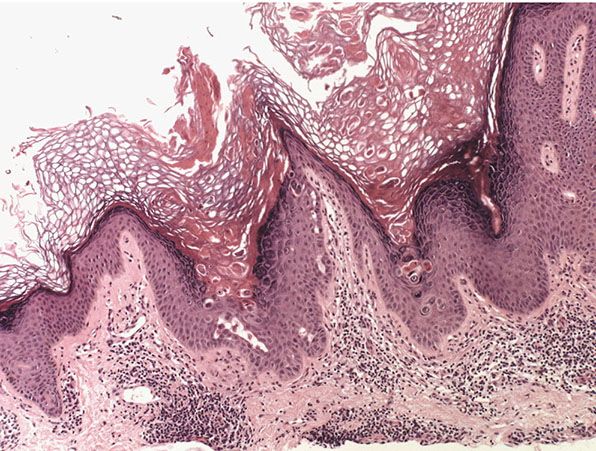

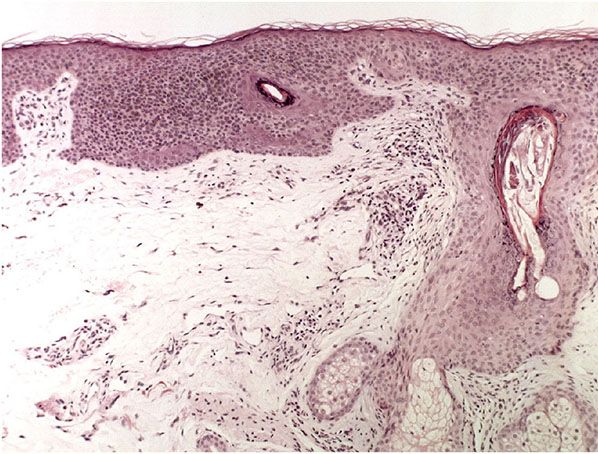

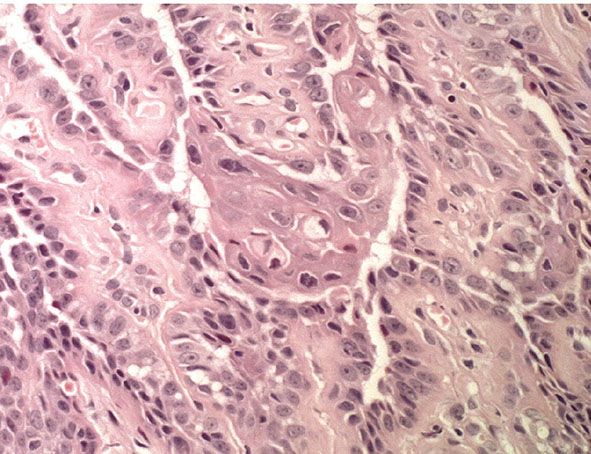

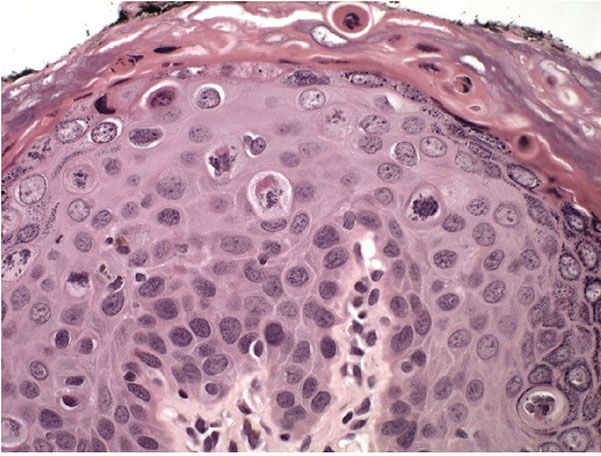

Histopathology. Focal suprabasal clefts with overlying acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells, some of which have the appearance of corps ronds (Fig. 29-5), have been seen as a single focus in the epidermis overlying such diverse lesions as dermatofibroma, basal cell epithelioma, melanocytic nevus, and chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (45), as well as in pityriasis rosea (56) and acral lentiginous malignant melanoma (Fig. 29-2) (57).

Figure 29-5 Incidental focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Focally, within the biopsy, there is suprabasal cleft formation with overlying dyskeratotic cells.

ORAL WHITE SPONGE NEVUS

Clinical Summary. First described in 1935 (58), oral white sponge nevus is a benign autosomal dominant disorder that affects noncornifying stratified squamous epithelia. It may be present at birth or have its onset in infancy, childhood, or adolescence (59). Extensive areas of the oral mucosa and sometimes the entire oral mucosa have a thickened, folded, creamy white appearance. In some instances, the rectal mucosa (58), vagina (60), nasal mucosa (61), or esophagus (62) is also involved. This distribution of lesions suggests that mutations in the epithelial keratins K4 and/or K13 may be responsible: A three-base-pair deletion in the helix initiation peptide of K4 has been reported in affected members of two families (63). Further studies of one large family suggested that a K13 gene was responsible (64).

The oral lesions seen in pachyonychia congenita are both clinically and histologically indistinguishable from a white sponge nevus (see Chapter 6) (61). Both leukoplakia and oral lichen planus are clinical differential diagnoses.

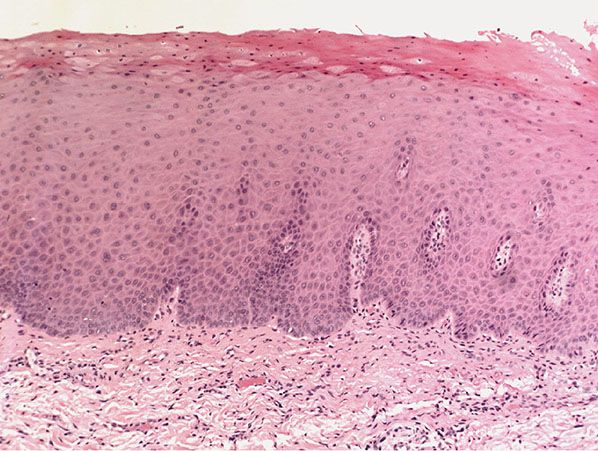

Histopathology. The oral epithelium shows hyperplasia with much more pronounced hydropic swelling of the epithelial cells than is normal for the oral mucosa. The swelling, though extensive, is focal (65). It extends into the rete ridges but spares the basal layer (66). The nuclei appear smaller than normal (59). The surface shows parakeratosis, as does the normal oral mucosa, and only rarely are there small accumulations of keratohyaline granules (60).

Pathogenesis. On electron microscopic examination, large cytoplasmic areas of the epithelial cells appear optically empty or contain only faint granular material. Tonofilaments are limited to the perinuclear and peripheral areas. The intercellular areas show irregular dilation, and large, irregularly shaped vacuoles are present within the cytoplasm (67). A possibly fundamental disturbance is the presence of numerous intracellular Odland bodies or membrane-coating granules (see Chapter 3), which are not extruded into the intercellular spaces (68).

Differential Diagnosis. The histologic picture of oral white sponge nevus is identical to that seen in pachyonychia congenita (see the preceding text) and to that of oral focal epithelial hyperplasia (67) and of leukoedema of the oral mucosa (see the following section).

Principles of Management. There is no standard treatment for this condition. Successful treatment with antifungals and antibiotics have been described.

LEUKOEDEMA OF THE ORAL MUCOSA

Clinical Summary. Leukoedema is a common benign condition that is significantly more prevalent in Afro-Caribbean individuals and is characterized by a blue, gray, or white appearance of the oral mucosa, in particular the buccal mucosa. When pronounced, it shows a clinical and histologic resemblance to oral white sponge nevus. However, leukoedema differs from white sponge nevus by being patchy rather than diffuse, by having exacerbations and remissions and adult onset, and by not being inherited (69). The exact etiology of the condition is unknown but it is thought to be caused by local irritation such as tobacco smoking. Thorough clinical examination should differentiate leukoedema from leukoplakia, lichen planus, and oral white sponge nevus (70).

Histopathology. In leukoedema of the oral mucosa, as in oral white sponge nevus, the suprabasal epithelial cells show marked intracellular edema. The nuclei appear smaller than normal.

Principles of Management. No treatment is required for this benign condition.

LINGUA GEOGRAPHICA

Clinical Summary. Geographic tongue, also referred to as superficial migratory glossitis, is a common benign clinical condition of unknown etiology. It typically presents on the dorsum of the tongue showing irregularly shaped red patches surrounded by a whitish, raised border a few millimeters wide (71). It is common, affecting 2% to 3% of the population (72). It is usually asymptomatic, with local loss of filiform papillae leading to the development of ulcer-like lesions that rapidly change color and size (73).

Histopathology. Whereas the dorsum of the tongue normally shows a granular and a horny layer, these layers are absent in the red patches of lingua geographica. Along the whitish border, the epithelium shows irregular thickening and infiltration of neutrophils. In its upper portion, the epithelium shows collections of neutrophils within the interstices of a sponge-like network formed by degenerated and thinned epithelial cells (74,75). The histologic picture thus shows Kogoj spongiform pustules, which are indistinguishable from those seen in pustular psoriasis.

Pathogenesis. The presence of spongiform pustules generally is regarded as diagnostic of pustular psoriasis and as almost specific for it (see Chapter 7), even though it rarely occurs in other pustules, such as those caused by Candida albicans (76). It has therefore been suggested that geographic tongue represents a localized form of pustular psoriasis (77). However, even though pustular psoriasis and lingua geographica may both show annular lesions on the tongue, pustular psoriasis of the mouth generally shows clinical evidence of pustules and is usually seen in other areas of the mouth also. It is therefore best to regard lingua geographica as a separate entity.

Principles of Management. Geographical tongue does not typically require any treatment. If it is associated with discomfort, corticosteroid ointments or rinses could be used.

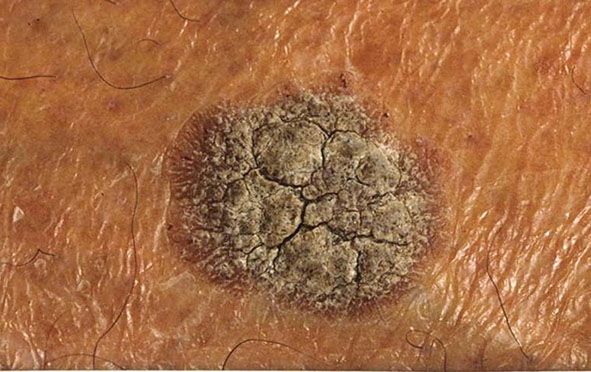

SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS

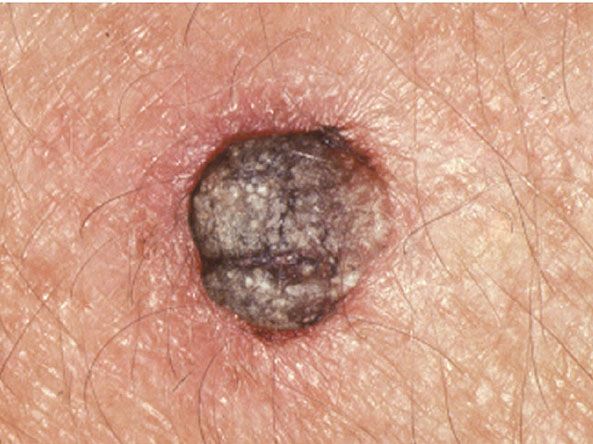

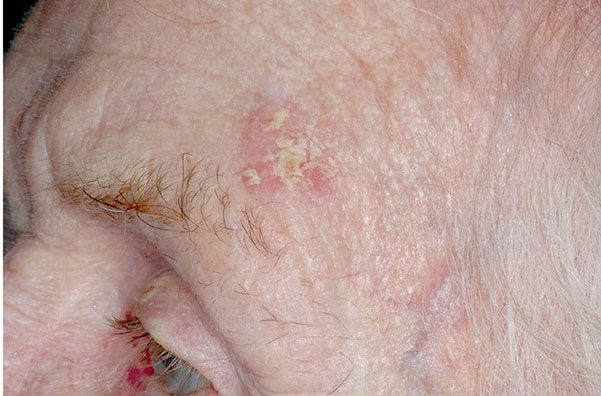

Clinical Summary. Seborrheic keratoses are very common: sometimes single but often multiple. They occur mainly on the trunk and face but also on the extremities, excluding palms and soles. They usually do not appear before middle age, but are present in about 20% of the elderly (77). They are sharply demarcated, often brownish in color, and slightly raised, often appearing as though stuck on the surface of the skin (Figs. 29-6 and 29-7). Most have a verrucous surface, and a soft, friable consistency. Some have a smooth surface but characteristically show keratotic plugs. Although most lesions measure only a few millimeters in diameter, some occasionally reach a size of several centimeters. Crusting and an inflammatory base are found if the lesion has been subjected to trauma. Occasionally, small examples are pedunculated, especially on the neck and upper chest, where they resemble soft fibromas (see Chapter 32). Malignant change is rare but has been reported in association with unusual clinical appearances to the seborrheic keratoses (78).

Figure 29-6 Seborrheic keratosis. The keratosis has a grayish, waxy appearance.

Figure 29-7 Seborrheic keratosis. Two keratoses lie close together and show variable pigmentation.

Histopathology. Seborrheic keratoses show a considerable variety of histologic appearances. Six types are generally recognized: irritated; adenoid or reticulated; plane; clonal; melanoacanthoma; inverted follicular keratosis; and benign squamous keratosis (Figs. 29-6 to 29-14). Often, more than one type is found in the same lesion. In addition, two clinical variants of seborrheic keratosis will be described—dermatosis papulosa nigra and stucco keratosis (Fig. 29-15).

Figure 29-8 Seborrheic keratosis. Low magnification. The keratosis is radially symmetric, has a flat base, and contains several horn cysts.

Figure 29-9 Seborrheic keratosis. High magnification. Most of the cells have a basaloid appearance, with interspersed horn cysts filled with keratin.

Figure 29-10 Pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Thin interwoven cords of basaloid cells show cytoplasmic melanin pigmentation and horn cysts.

Figure 29-11 Clonal seborrheic keratosis, showing focal variation in pigmentation.

Figure 29-12 Clonal seborrheic keratosis showing foci of basaloid cells surrounded by more eosinophilic squamous cells.

Figure 29-13 Irritated seborrheic keratosis showing inflammation of the adjacent skin.

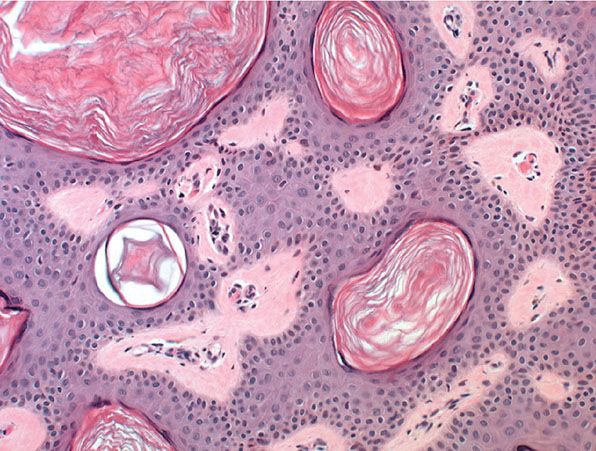

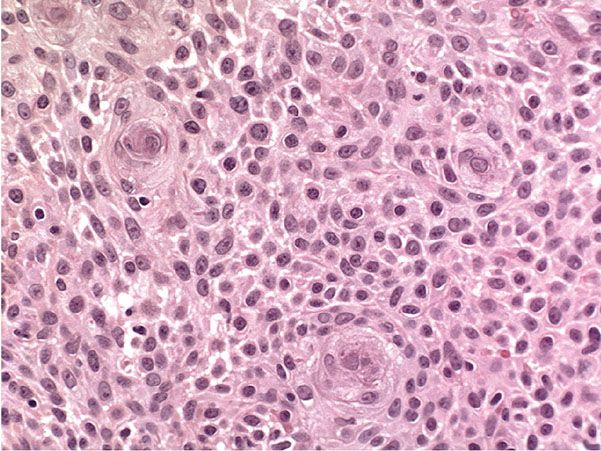

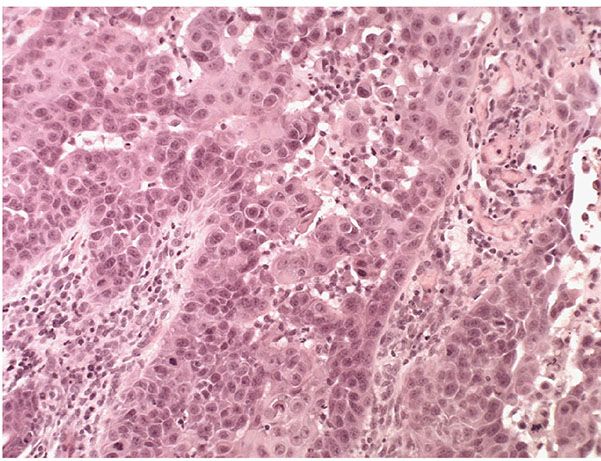

Figure 29-14 Inverted follicular keratosis. Squamous eddies are present, composed of whorls of squamous cells. There is no substantial cytologic atypia.

All types of seborrheic keratosis have in common hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. The acanthosis in most instances is due entirely to upward extension of the tumor. Thus, the lower border of the tumor is even, and generally lies on a straight line that may be drawn from the normal epidermis at one end of the tumor to the normal epidermis at the other end (see Fig. 29-8). Two types of cells are usually seen in the acanthotic epidermis: squamous cells and basaloid cells. The former have the appearance of squamous cells normally found in the epidermis; the basaloid cells are small and uniform in appearance and have a relatively large nucleus. In areas of slight intercellular edema, intercellular bridges can be easily recognized (79). Thus, they resemble the basal cells found normally in the basal layer of the epidermis.

Irritated Type and Inverted Follicular Keratosis

Clinical Summary. Irritated seborrheic keratosis will typically appear inflamed, with inflammation extending to involve the surrounding skin (Fig. 29-15).

Figure 29-15 Stucco keratoses: multiple small, white, and gray-white seborrheic keratoses.

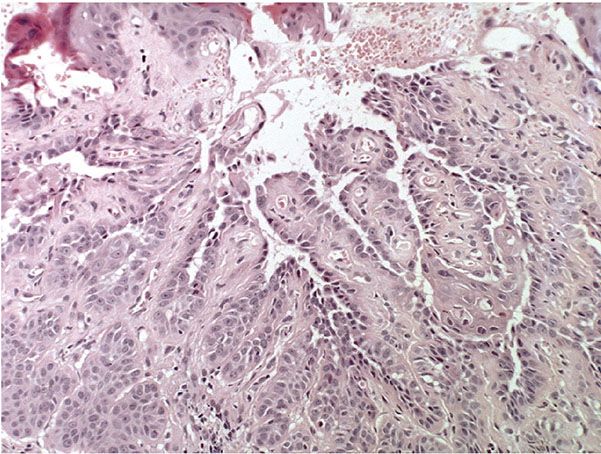

Histopathology. Squamous cells typically outnumber basaloid cells. The characteristic feature is the presence of numerous whorls or eddies composed of eosinophilic, flattened squamous cells arranged in an onion-peel fashion, resembling poorly differentiated horn pearls (Fig. 29-14). These “squamous eddies” are easily differentiated from the horn pearls of SCC by their large number, small size, and circumscribed configuration. Irritated seborrheic keratoses, in addition, may show areas of downward proliferation breaking through the horizontal demarcation generally present in nonirritated seborrheic keratoses (80,81). Frequently, some of these proliferations are seen to originate from the walls of keratin-filled invaginations. Inflammation beneath irritated seborrheic keratoses usually is mild or absent, indicating that irritated seborrheic keratoses are different from inflamed seborrheic keratoses.

In a few instances, acantholysis has been observed within tumor nests composed of squamous cells (82). These acantholytic changes differ from those occurring in incidental focal acantholytic dyskeratosis by not showing suprabasal location or dyskeratotic cells resembling corps ronds (83).

Pathogenesis. The formation of numerous squamous eddies is the result of the “activation” of resting basaloid cells into squamous cells. This unique and highly diagnostic feature of irritated or activated seborrheic keratoses, as well as their downward proliferation, is the result of irritation. This has been proved experimentally by the excision of seborrheic keratoses either after a previous biopsy (84) or after irritation with croton oil (85).

The identical histologic picture as seen in irritated seborrheic keratosis has been described under the designations of inverted follicular keratosis (86,87) and follicular poroma (88,89). As these terms indicate, the authors regard the keratin-filled invaginations as follicular infundibula and the proliferations arising from them as composed of cells of the follicular infundibulum. The follicular infundibulum consists of cells with the same type of keratinization as the surface epidermis, and there is evidence that seborrheic keratoses incorporate cells of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle and are partially derived from these cells. Seborrheic keratoses, like inverted follicular keratoses, occur exclusively on hair-bearing skin. Some seborrheic keratoses even contain aggregates of vellus hairs within the keratinous invaginations, an occurrence analogous to trichostasis spinulosa (see Chapter 18) (90). Although some authors merely concede that irritated seborrheic keratoses and inverted follicular keratoses may be histologically indistinguishable (81,91,92), others regard the two disorders as identical (80,90,93). Because of their histologic similarity and particularly because of the highly specific appearance of the squamous eddies that occur in these two conditions, they are best regarded as identical.

Adenoid or Reticulated Type

In the adenoid or reticulated type of seborrheic keratosis, numerous thin tracts of epidermal cells extend from the epidermis and show branching and interweaving in the dermis. Many tracts are composed of only a double row of basaloid cells. Horn cysts and pseudo–horn cysts are absent in purely reticulated lesions; however, the reticulated type often also shows areas of the acanthotic type, and horn cysts and pseudo–horn cysts are commonly seen in these areas. The basaloid cells of the reticulated type of seborrheic keratosis usually show marked hyperpigmentation.

There is both clinical and histologic evidence of a close relationship between solar or senile lentigo senilis and the reticulated type of seborrheic keratosis. A lesion of solar lentigo may even become a reticulated seborrheic keratosis through exaggeration of the process of downward budding of pigmented basaloid cells (see Chapter 28) (94).

Acanthotic Type

In the acanthotic type, the most common type of seborrheic keratosis, hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis often are slight, but the epidermis is greatly thickened. Although only narrow papillae are included in the thickened epidermis in some cases, one can see in other lesions a retiform pattern composed of thick, interwoven tracts of epithelial cells surrounding islands of connective tissue. Horny invaginations that on cross sections appear as pseudo–horn cysts are numerous. In addition, there are also true horn cysts, which, like the pseudo–horn cysts, show sudden and complete keratinization with only a very thin granular layer.

The true horn cysts begin as foci of orthokeratosis within the substance of the lesion (95). In time, they enlarge and are carried by the current of epidermal cells toward the surface of the lesion, where they unite with the invaginations of surface keratin. In the greatly thickened epidermis, basaloid cells usually outnumber squamous cells.

The amount of melanin in seborrheic keratoses of the acanthotic type is often greater than normal. Excess amounts of melanin are seen in about one-third of the specimens stained with hematoxylin–eosin (96); staining with silver reveals excess amounts in about two-thirds of the cases (97). In dopa-stained sections, melanocytes are limited to the dermal–epidermal junctional layer present at the base of the tumor and at the interfaces between the tumor tracts and the islands of dermal stroma (85). The melanin, largely present in keratinocytes, is in most instances also limited to keratinocytes located at the dermal–epidermal junction. Only deeply pigmented lesions show melanin widely distributed throughout the tumor within basaloid cells (98).

A mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate is seen quite frequently in the dermis underlying a seborrheic keratosis. The inflammation may impinge on the tumor in a lichenoid or eczematous pattern. In the lichenoid pattern, a bandlike infiltrate is seen hugging the basal cell layer of the tumor. In the eczematous pattern, there is exocytosis leading to spongiosis. Squamous eddies, typical of irritated seborrheic keratoses, are only rarely seen in inflamed seborrheic keratoses (99).

Formation of an in situ carcinoma within an acanthotic seborrheic keratosis, the so-called bowenoid transformation, is seen occasionally (78,100). It seems to occur predominantly in lesions located in sun-exposed areas of the skin; so sun damage may be a factor (101). In one reported case, a metastasis in a regional lymph node was found (102). On rare occasions, a basal cell epithelioma may form within an acanthotic seborrheic keratosis and may extend from there into the underlying dermis (103,104).

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination has confirmed the light microscopic impression that the small basaloid cells seen in the acanthotic type of seborrheic keratosis are related to cells of the epidermal basal cell layer rather than to the basaloma cells of basal cell epithelioma. They possess a fair number of desmosomes and a moderate number of tonofilaments that differ from those present in cells of the epidermal basal cell layer only by showing less orientation (105).

Hyperkeratotic Type

In the hyperkeratotic type, also referred to as the digitate or serrated type, hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis are pronounced, whereas acanthosis is not very conspicuous. The numerous digitate upward extensions of epidermis-lined papillae often resemble church spires. The histologic picture then resembles that seen in acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (see Chapter 6). The epidermis consists largely of squamous cells, although small aggregates of basaloid cells may be seen here and there. As a rule, no excess amounts of melanin are found.

Clonal Type

In the clonal, or nesting, type of seborrheic keratosis, well-defined nests of cells are located within the epidermis. In some instances, the nests resemble foci of basal cell epithelioma because the nuclei appear small and dark-staining and intercellular bridges are seen in only a few areas (see Figs. 29-11 and 29-12) (106). The histologic picture in such cases has been erroneously interpreted by some authors as representing an intraepidermal epithelioma of Borst–Jadassohn (see Chapter 30) (107). In other instances of clonal seborrheic keratosis, the nests are composed of fairly large cells showing distinct intercellular bridges, with the nests separated from one another by strands of cells exhibiting small, dark nuclei.

Melanoacanthoma

This rather rare variant of pigmented seborrheic keratosis (98) differs from the usual type of pigmented seborrheic keratosis by showing a marked increase in the concentration of melanocytes. Rather than being confined to the basal layer of the tumor lobules, many melanocytes are scattered throughout the tumor lobules (98,108). In some instances, well-defined islands of basaloid cells intermingled with many melanocytes are distributed through the tumor (109). The melanocytes are large and richly dendritic and contain variable amounts of melanin. The block in transfer of melanin from melanocytes to keratinocytes often is only partial (108), although in some instances nearly all the melanin is retained in the melanocytes (110).

Pathogenesis. Melanoacanthoma is a benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and keratinocytes (98).

Principles of Management. Treatment for asymptomatic seborrheic keratosis is largely carried out for cosmetic reasons. Symptomatic lesions are commonly removed by cryotherapy, curettage, or shave excision. Other methods for removal such as laser vaporization and electrodesiccation are also performed.

DERMATOSIS PAPULOSA NIGRA

Clinical Summary. Dermatosis papulosa nigra is a benign condition considered by some to be a type of seborrheic keratosis. It is found in about 35% of all adult blacks and often has its onset during adolescence (111), and has been described in a 3-year-old child (112). It also occurs among Asians, although the exact incidence in unknown. The lesions are located predominantly on the face, especially in the malar regions, but they also may occur on the neck and upper trunk. They usually consist of small, smooth, pigmented papules, except on the neck and trunk, where they may be pedunculated. Dermatosis papulosa nigra is likely to be genetically determined, with 40% to 50% of patients having a family history. It is thought to be due to a nevoid mutation of the hair follicle (111).

Histopathology. The lesions have the histologic appearance of seborrheic keratoses but are smaller. Most lesions are of the acanthotic type and show thick interwoven tracts of epithelial cells. The cells are largely squamous in appearance, with only a few basaloid cells (111). Horn cysts are quite common. An occasional lesion shows a reticulated pattern in which the tracts are composed of a double row of basaloid cells. Melanin pigmentation is pronounced in all lesions.

Principles of Management. Treatment for dermatosis papulosa nigra is usually carried out for cosmetic reasons. Hypopigmentation posttreatment is a concern, and it is advised to perform treatment on a small area of skin to begin with. Dermatosis papulosa nigra is commonly treated with snip excision, curettage, and light electrodesiccation.

STUCCO KERATOSIS

Clinical Summary. This entity was first described by Kocsard and Ofner in 1965 (113) and further elaborated later (113a). Stucco keratoses are benign small gray-white seborrheic keratoses measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter, located in symmetric arrangement on the distal portions of the extremities, especially the ankles (Fig. 29-15). They can easily be scraped off without any resultant bleeding.

The name stucco keratosis is derived from the “stuck-on” appearance of the lesions. No known cause has been found for their development, and they are not thought to be inherited genetically. However, DNA from HPV types 9, 16, 23b, DL322, and a variant of HPV 37 was detected with nested polymerase chain reaction analysis of lesional material from a 75-year-old man with extensive stucco keratoses (114).

Histopathology. Stucco keratoses have the appearance of the hyperkeratotic type of seborrheic keratosis, showing the church-spire pattern of upward-extending papillae (113,113a,115,116). Horn cysts and basaloid cells are usually absent (113,113a).

Principles of Management. As for seborrheic keratosis, treatment is performed for cosmetic reasons. Destruction with cryotherapy or curettage or simple excision can be used for removal.

LESER–TRÉLAT SIGN

Clinical Summary. The Leser–Trélat sign is characterized by the sudden appearance of numerous seborrheic keratoses in association with a malignant tumor. Although many reports have appeared in recent years concerning this sign and although its existence is accepted, it is not always easy to decide which cases should be included. In some instances, numerous seborrheic keratoses develop on inflamed skin, but this does not represent the Leser–Trélat sign (99). A review of 40 cases that were accepted as representing the Leser–Trélat sign (117) showed that 30% had “malignant” acanthosis nigricans (see Chapter 17) either accompanying (118) or following the sign (119). Thus, the Leser–Trélat sign has been interpreted as “an incomplete form of acanthosis nigricans” (120) or as “potentially representing an early stage of acanthosis nigricans” (119).

Although the malignant tumor in 67% of the reported cases consisted of an abdominal adenocarcinoma (117,121), the remaining 33% included many different types of malignancies, including leukemia (122) and mycosis fungoides (123). More controversially, a case–control study failed to demonstrate a specific association between eruptive seborrheic keratoses and internal cancer risk (124).

Histopathology. The seborrheic keratoses in the Leser–Trélat sign are the same as other seborrheic keratoses. The hyperkeratotic form is indistinguishable from malignant acanthosis nigricans (117,125).

LARGE CELL ACANTHOMA

Clinical Summary. Large cell acanthoma occurs as a slightly hyperkeratotic, sharply demarcated patch, usually on sun-exposed skin of the head or extremities. As a rule, it measures less than 1 cm in size. Generally, it is a solitary lesion; occasionally multiple lesions are observed (126–128).

Histopathology. Within a well-demarcated area of the epidermis, the scattered large keratinocytes are about twice the normal size and have proportionally large nuclei. There may be a disordered arrangement of the keratinocytes (Fig. 29-16). Unlike in an actinic keratosis, there is no parakeratosis.

Figure 29-16 Large cell acanthoma. Keratinocytes are increased in size and arranged in a disorderly manner.

Pathogenesis. The lesion is aneuploid, with various stages of development, and is probably related to stucco keratosis (126,128).

Principles of Management. Destruction or excision is the option for the treatment of this benign entity.

CLEAR CELL ACANTHOMA

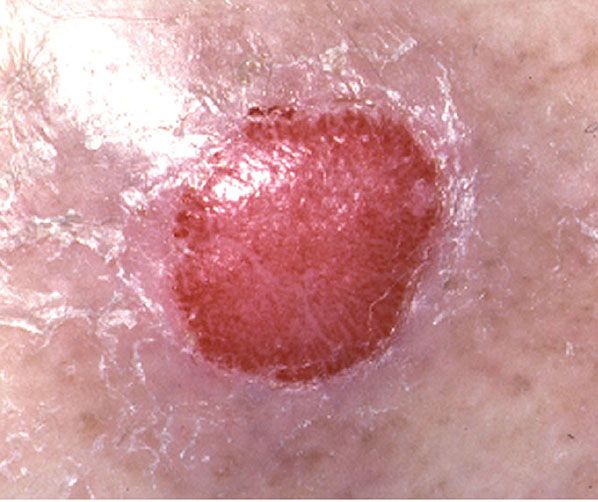

Clinical Summary. Clear cell acanthoma, a tumor that is clinically and histologically quite distinct, was first described in 1962 (129). It is not rare. Typically, the lesions are solitary and occur on the legs. They are slowly growing, sharply delineated, red nodules or plaques 1 to 2 cm in diameter and usually covered with a thin crust and exuding some moisture. A collarette is often seen at the periphery. It has been said that the lesion appears stuck-on, like a seborrheic keratosis, and is vascular, like a granuloma pyogenicum (Fig. 29-17) (130,131).

Figure 29-17 Clear cell acanthoma. A raised, sharply demarcated red patch.

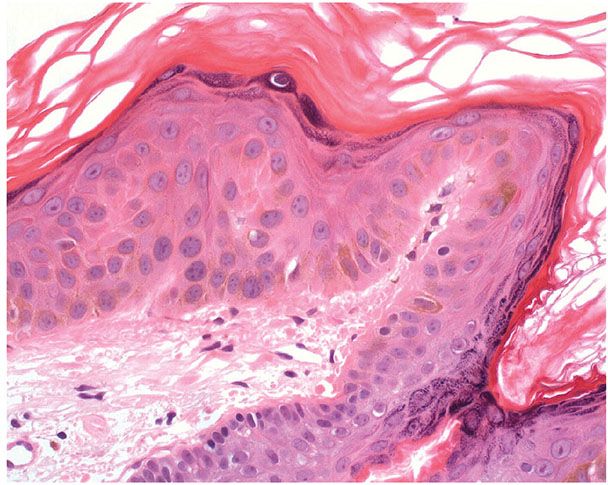

Histopathology. Within a sharply demarcated area of the epidermis, all epidermal cells, with the exception of cells of the basal cell layer, appear strikingly clear and slightly enlarged (Figs. 29-18 and 29-19). The nuclei of the clear epidermal cells appear normal. When staining is carried out with the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction, the presence of large amounts of glycogen is revealed within the cells (129,132).

Figure 29-18 Clear cell acanthoma. The cells within the lesion appear pale by comparison with the adjacent normal epidermis.

Figure 29-19 Clear cell acanthoma. High magnification. Neutrophils and nuclear dust are scattered through the clear cells of the lesion.

Slight spongiosis is present between the clear cells. The rete ridges are elongated and may show intertwining (133). The surface shows parakeratosis with few or no granular cells. The acrosyringia and acrotrichia within the tumor retain their normal stainability (132). There is an absence of melanin within the tumor cells, but dendritic melanocytes containing melanin are occasionally seen interspersed between the clear cells (132,134).

A conspicuous feature in most lesions is the presence throughout the epidermis of numerous neutrophils, many of which show fragmentation of their nuclei (Fig. 29-19). The neutrophils often form microabscesses in the parakeratotic horny layer (135,136). Dilated capillaries are seen in the elongated papillae and often also in the dermis underlying the tumor (132). In addition, a mild to moderately severe cellular infiltrate composed largely of lymphoid cells is present in the dermis. Some clear cell acanthomas appear papillomatous; so they have the configuration of a seborrheic keratosis (137).

Beneath the tumor, some cases have shown hyperplasia of sweat ducts (135) or syringoma-like proliferations (138).

Pathogenesis. On histochemical examination, phosphorylase is absent in clear cell acanthoma except for the basal cell layer. This enzyme normally is present in the epidermis and is necessary for the degradation of glycogen (139).

Electron microscopy reveals glycogen granules in the tumor cells, except in the cells of the basal cell layer. In the lower portion of the tumor, the glycogen granules are seen largely around the nuclei. In the upper portion, however, the amount of glycogen is increased, and the granules are seen to infiltrate between the tonofilaments (139).

Although the melanocytes, including their dendrites, contain melanosomes, hardly any melanosomes are present within the tumor cells, indicating a blockage in the transfer of melanosomes from the melanocytes to the tumor cells (140).

Principles of Management. Simple destruction or excision is adequate for removal and lesions do not usually recur.

EPIDERMAL OR INFUNDIBULAR CYST

Clinical Summary. Epidermal cysts are slowly growing, elevated, round, firm, intradermal or subcutaneous tumors that cease growing after having reached 1 to 5 cm in diameter. They occur most commonly on the face, scalp, neck, and trunk (Fig. 29-20). Although most epidermal cysts arise spontaneously in hair-bearing areas, occasionally they occur on the palms or soles (141,142) or form as the result of trauma (143). Usually a patient has only one or a few epidermal cysts, rarely many. In Gardner syndrome, however, numerous epidermal cysts occur, especially on the scalp and face (see Chapter 32).

Figure 29-20 Epidermal cyst. The cyst distends the overlying skin of the cheek.

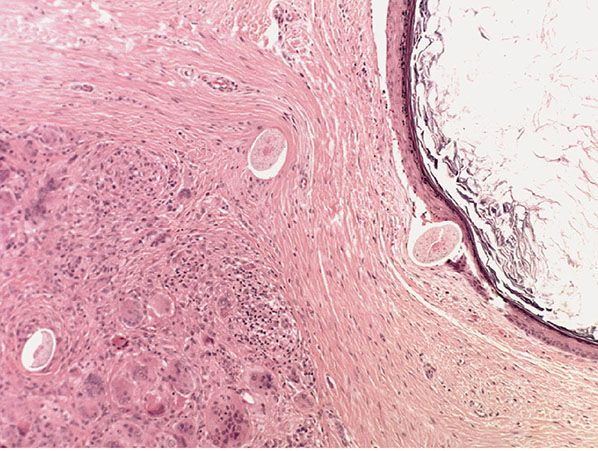

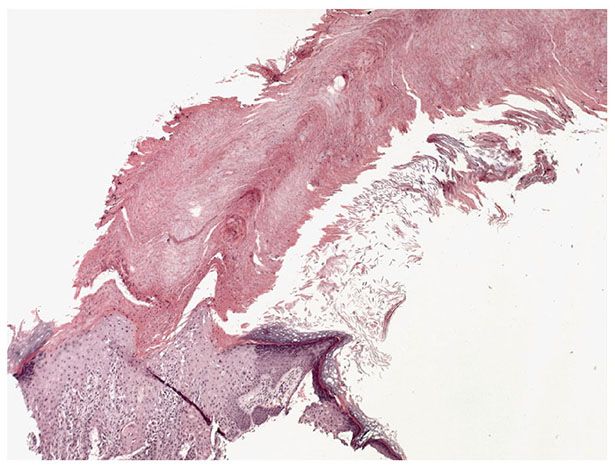

Histopathology. Epidermal cysts have a wall composed of true epidermis, as seen on the skin surface and in the infundibulum of hair follicles, the infundibulum being the uppermost part of the hair follicle that extends down to the entry of the sebaceous duct. In young epidermal cysts, several layers of squamous and granular cells can usually be recognized (Fig. 29-21). In older epidermal cysts, the wall often is markedly atrophic, either in some areas or in the entire cyst, and may consist of only one or two rows of greatly flattened cells. The cyst is filled with horny material arranged in laminated layers. In sections stained with hematoxylin–eosin, melanocytes and melanin pigmentation of keratinocytes can be seen only rarely in epidermal cysts of whites but frequently in epidermal cysts of blacks. Silver stains reveal that most of the melanin is located in the basal layer of the cyst lining, but some melanin is also seen in the contents of the cyst (144).

Figure 29-21 Epidermal cyst. The cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium with a granular layer. The cyst is filled with keratin flakes.

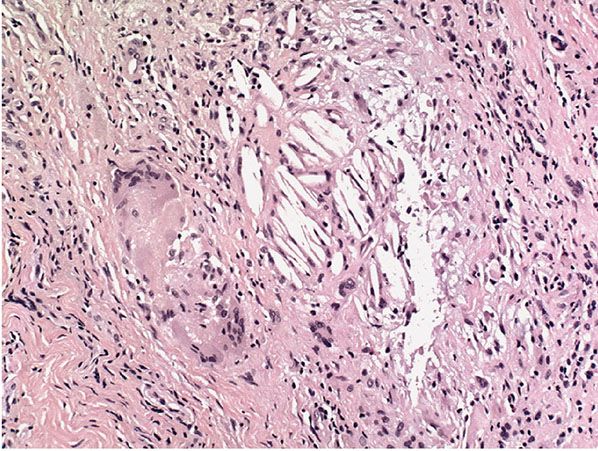

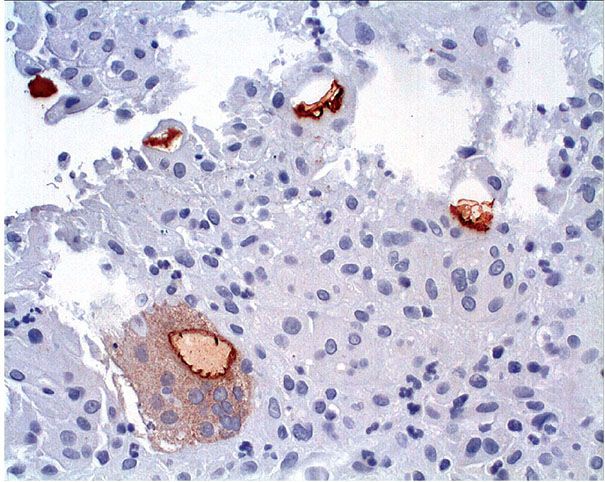

When an epidermal cyst ruptures and the contents of the cyst are released into the dermis, a considerable foreign-body reaction with numerous multinucleated giant cells results, forming a keratin granuloma (Figs. 29-22 and 29-23). The foreign-body reaction usually causes disintegration of the cyst wall. However, it may lead to a pseudocarcinomatous proliferation in remnants of the cyst wall, simulating an SCC (145). Melanocytes, melanin, and melanophages have been reported in the walls of epidermal cysts in some Indians (146) and a Japanese patient (147).

Figure 29-22 Keratin granuloma. At the edge of a partially ruptured cyst, cholesterol clefts form part of a keratin granuloma.

Figure 29-23 Keratin granuloma. Cytokeratin staining highlights keratin flakes in giant cells within a keratin granuloma.

Development of a basal cell epithelioma (148), a lesion of Bowen disease (149), or an SCC (150) in epidermal cysts is a rare event. In cases of SCC, the tumor is apt to be of low malignancy and does not metastasize. It is likely that some cases that were regarded in the past as malignant degeneration of epidermal cysts now are interpreted either as pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia in a ruptured epidermal cyst (145) or as proliferating trichilemmal tumor (see Chapter 30) (151).

Pathogenesis. It is widely assumed that most spontaneously arising epidermal cysts are related to the follicular infundibulum. The occurrence of hybrid cysts with partially epidermal and partially trichilemmal lining favors this assumption (152). Epidermal cysts in nonfollicular regions, such as the palms or soles, probably form as a result of the traumatic implantation of epidermis into the dermis or subcutis (141,142).

As seen by electron microscopy, the keratinization in epidermal cysts is identical to that in the surface epidermis and in the pilosebaceous infundibulum because the keratin located within the keratinized cells consists of relatively electron-lucent tonofilaments embedded in an electron-dense interfilamentous substance derived from keratohyaline granules. The keratinized cells of the cyst content have a markedly flattened, elongated appearance and are surrounded by a thick marginal band rather than by a plasma membrane. Desmosomes are no longer present (153).

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS–ASSOCIATED CYST (VERRUCOUS CYST)

Clinical Summary. These cysts are found most frequently on the soles of the feet but have also been reported on the scalp, face, back, and extremities. They may have the typical appearance of a cyst or possibly suggest dermatofibroma or BCC.

Histopathology. The cysts are lined by epidermal-type epithelium showing koilocytic changes and hypergranulosis suggestive of verrucous change.

Pathogenesis. HPV has been demonstrated in the epithelium by molecular methods. It is unclear whether these cysts are traumatic implantations of verrucae or represent epidermal cysts with secondary HPV infection (154).

MILIA

Clinical Summary. Milia are multiple, superficially located, white, globoid, firm lesions generally only 1 to 2 mm in diameter. A distinction is made between primary milia, which arise spontaneously on the face in predisposed individuals, and secondary milia, which occur either in diseases associated with subepidermal bullae, such as bullous pemphigoid, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (155,156), and porphyria cutanea tarda, or after dermabrasion (157) and other trauma.

Histopathology. Primary milia of the face are derived from the lowest portion of the infundibulum of vellus hairs at about the level of the sebaceous duct. The milia often are still connected with the vellus hair follicle by an epithelial pedicle. Primary milia are small cysts differing from epidermal cysts only in size. They are lined by a stratified epithelium a few cell layers thick and contain concentric lamellae of keratin (157).

Secondary milia have the same histologic appearance as primary milia (157). They may develop from any epithelial structure and on serial sections may still show a connection to the parent structure, whether a hair follicle, sweat duct, sebaceous duct, or epidermis (158). Secondary milia that follow blistering arise in most instances from the eccrine sweat duct and very rarely from a hair follicle. In a certain percentage of cases, however, no connection is found with any skin appendage, suggesting that the milia have developed from aberrant epidermis (159). In milia derived from eccrine sweat ducts, the sweat ducts are frequently seen to enter the cyst wall at the bottom of the milium (157,159).

Pathogenesis. Primary milia of the face represent a keratinizing type of benign tumor (157). In contrast, secondary milia represent retention cysts caused by proliferative tendencies of the epithelium after injury (160).

Principles of Management. Milia are benign and can be left untreated. Surgical treatment is usually performed for cosmetic reasons. An incision with a cutting-edge needle and manual expression of the contents is an easy and cost-effective treatment. Treatments with electrodesiccation, laser, dermabrasion, and cryosurgery have been reported to be effective.

PILAR OR TRICHILEMMAL CYST

Clinical Summary. Pilar or trichilemmal cysts are clinically indistinguishable from epidermal cysts but differ from them in frequency and distribution. They are less common than epidermal cysts, constituting only about 25% of the combined material; about 90% occur on the scalp (Fig. 29-24). Pilar cysts often show an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and are solitary in only 30% of the cases, with 10% of patients having more than 10 cysts (161). Furthermore, in contrast to epidermal cysts, pilar cysts are easily enucleated and appear as firm, smooth, white-walled cysts (Fig. 29-25) (162).

Figure 29-24 Pilar cyst. Clinically similar to an epidermal cyst, but more frequently seen on the scalp.

Figure 29-25 Pilar cyst. The cyst has a well-defined margin, as seen at the time of excision.

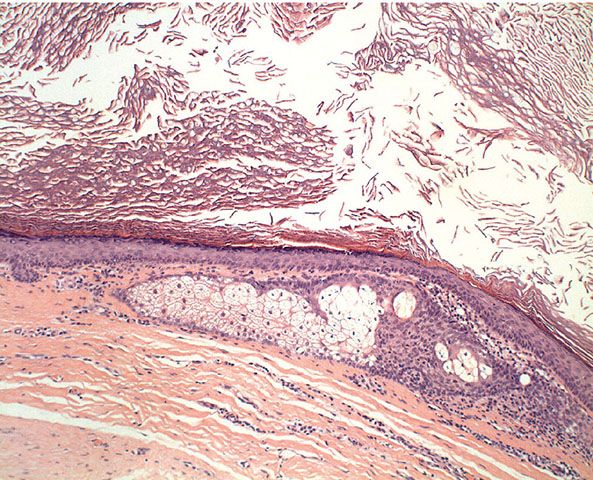

Histopathology. The wall of trichilemmal cysts is composed of epithelial cells possessing no clearly visible intercellular bridges. The peripheral layer of cells shows a distinct palisade arrangement not seen in epidermal cysts. The epithelial cells close to the cystic cavity appear swollen and are filled with pale cytoplasm (Fig. 29-26). These swollen cells do not produce a granular layer but generally undergo abrupt keratinization, although nuclear remnants are occasionally retained in a few cells. The content of the cysts consists of homogeneous eosinophilic material (153).

Figure 29-26 Pilar cyst. The cyst is lined by a squamous epithelium without a granular layer and with swelling of the cells close to the cyst cavity that is filled with homogeneous keratin.

Whereas focal calcification of the cyst content does not occur in epidermal cysts, foci of calcification are seen in approximately one-fourth of trichilemmal cysts (146). A considerable foreign-body reaction results when the wall of a trichilemmal cyst ruptures, and the cyst may then undergo partial or complete disintegration.

Trichilemmal cysts frequently disclose small, acanthotic foci in their walls that are indistinguishable from solid areas, as seen in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (163). The association of a trichilemmal cyst with tumor lobules of a proliferating trichilemmal cyst is also seen occasionally (see Chapter 30) (161).

Pathogenesis. Pilar cysts were originally called sebaceous cysts. The name was changed when it became apparent that the keratinization in them is analogous to the keratinization that takes place in the outer root sheath of the hair, or trichilemma (164). The outer root sheath of the hair does not keratinize wherever it covers the inner root sheath. It keratinizes normally in two areas—the follicular isthmus of anagen hairs and the sac surrounding catagen and telogen hairs—because in these two regions the inner root sheath has disappeared. The follicular isthmus of anagen hairs is the short, middle portion of the hair follicle, extending upward from the attachment of the arrector pili muscle to the entrance of the sebaceous duct. At the lower end of the follicular isthmus, the inner root sheath sloughs off, exposing the outer root sheath, which, in its exposed portion, undergoes a specific type of homogeneous keratinization without the interposition of a granular layer. This type of trichilemmal keratinization also takes place in the sac surrounding catagen and telogen hairs because hairs in these stages have lost their inner root sheath. The differentiation toward hair keratin in trichilemmal cysts has been confirmed by immunohistochemical staining because they stain with antikeratin antibodies derived from human hair, in contrast to epidermal cysts, which stain with antikeratin antibodies obtained from human callus (165).

Electron microscopic examination of the epithelial lining of trichilemmal cysts shows that, on their way from the peripheral layer toward the center, the epithelial cells have an increasing number of filaments in their cytoplasm. The transition from nucleate to anucleate cells is abrupt and is associated with the loss of all cytoplasmic organelles. The junction between the keratinizing and keratinized cells shows interdigitations (166). The keratinized cells are filled with tonofilaments and, unlike those in epidermal cysts, retain their desmosomal connections (153).

Differential Diagnosis. Even though both the pilar cyst and the proliferating trichilemmal cyst show trichilemmal types of keratinization and can occur together, one is essentially a cyst and the other essentially a solid, tumorlike proliferation. The latter is therefore discussed under the section Tumors with Differentiation toward Hair Follicle Components in Chapter 30.

STEATOCYSTOMA MULTIPLEX

Clinical Summary. Steatocystoma multiplex is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. One observes numerous small, rounded, moderately firm cystic nodules that are adherent to the overlying skin and usually measure 1 to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 29-27). When punctured, the cysts discharge an oily or creamy fluid and, in some instances, also small hairs (167–170). They are found most commonly in the axillae, in the sternal region, and on the arms. Steatocystoma also occurs occasionally as a solitary, noninherited tumor in adults, where it is referred to as steatocystoma simplex (171).

Figure 29-27 Steatocystoma multiplex. Multiple small, rounded cysts are present in the axilla.

Histopathology. The cysts have walls that are intricately folded with several layers of epithelial cells, although in atrophic areas only two or three layers of flat cells may be present. Elsewhere there is a basal layer in palisade arrangement, above which are two or three layers of swollen cells without recognizable intercellular bridges. Central to these cells, there is a thick, homogeneous, eosinophilic horny layer that forms without an intervening granular layer. It protrudes irregularly into the lumen in a fashion simulating the decapitation secretion of apocrine glands (Fig. 29-28) (172).

Figure 29-28 Steatocystoma multiplex. The cyst wall shows intricate folding. The lining stratified squamous epithelium has sebaceous gland lobules within and close to it.

A characteristic feature seen in most lesions of steatocystoma is the presence of flattened sebaceous gland lobules either within or close to the cyst wall (173). In some cysts, invaginations resembling hair follicles extend from the cyst wall into the surrounding stroma, and in rare instances, true hair shafts are seen within them, indicating that the invaginations represent the outer root sheath of hairs. In a few cysts, the lumen contains clusters of hair, mainly of lanugo size but partially of intermediate character (174). When stained with the PAS reaction, the cells of the cyst wall are found to be rich in glycogen.

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination has shown that the cyst wall consists of keratinizing cells. Nearest to the lumen, the cyst wall consists of several layers of flattened, very elongated horny cells interconnected by desmosomes.

It appears likely that differentiation in the cyst wall of steatocystoma multiplex is to a large extent in the direction of the sebaceous duct (175,176). The sebaceous duct and the outer root sheath are composed of similar cells, but undulation and thinning of the horny layer and the existence of sebaceous cells in the cyst wall are characteristic features of the sebaceous gland side of the sebaceous duct (176). Sebaceous duct cells, like outer root sheath cells, contain abundant glycogen and amylophosphorylase, keratinize without the interposition of keratohyaline granules, and, on electron microscopic examination, retain their desmosomes after keratinization (172).

PIGMENTED FOLLICULAR CYST

Clinical Summary. This is an uncommon pigmented lesion resembling a nevus.

Histopathology. The cyst wall consists of infundibular epidermis. The cyst contains, in addition to laminated keratin, numerous large pigmented hair shafts. One or two growing hair follicles are seen in the wall of the cyst (177).

DERMOID CYST

Clinical Summary. Dermoid cysts are subcutaneous cysts that usually are present at birth. They occur most commonly on the head, mainly around the eyes, and occasionally on the neck. When located on the head, they often are adherent to the periosteum. Usually they measure between 1 and 4 cm in diameter.

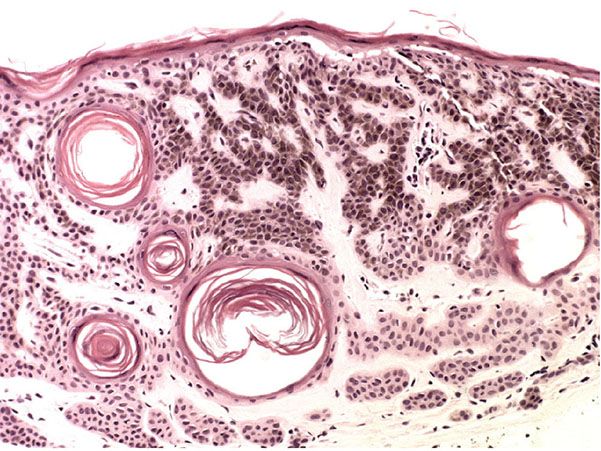

Histopathology. Dermoid cysts, in contrast to epidermal cysts, are lined by an epidermis that possesses various epidermal appendages that are usually fully matured (Figs. 29-29 and 29-30). Hair follicles containing hairs that project into the lumen of the cyst are often present. In addition, the dermis of dermoid cysts usually contains sebaceous glands, often eccrine glands, and, in about 20% of the cases, apocrine glands that have matured (178).

Figure 29-29 External angular dermoid cyst. The cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, with adnexal structures in the wall.

Figure 29-30 External angular dermoid cyst. In this example, the cyst has ruptured, producing an adjacent granuloma containing hair shafts derived from the cyst.

Pathogenesis. Dermoid cysts are a result of the sequestration of skin along the lines of embryonic closure.

BRONCHOGENIC AND THYROGLOSSAL DUCT CYSTS

Clinical Summary. Bronchogenic cysts are rare. They are small, solitary lesions seen most commonly in the skin or subcutaneous tissue just above the sternal notch. Rarely, they are located on the anterior aspect of the neck or on the chin. As a rule, they are discovered shortly after birth. They may show a draining sinus.

Thyroglossal duct cysts are clinically indistinguishable from bronchogenic cysts, except that they are usually located on the anterior aspect of the neck.

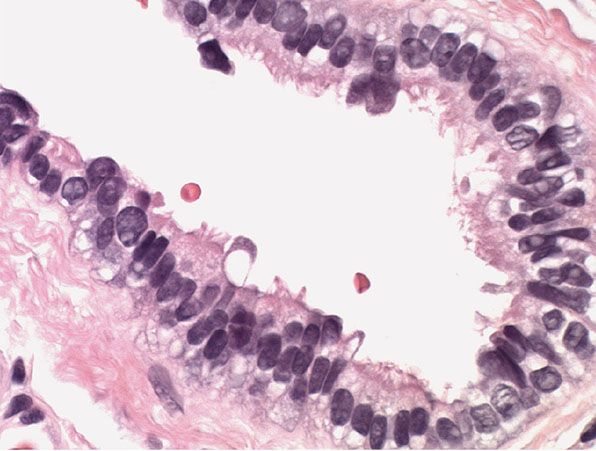

Histopathology. Bronchogenic cysts are lined by a mucosa consisting of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium (Fig. 29-31). Goblet cells may be interspersed. The wall frequently contains smooth muscle and mucous glands but only rarely contains cartilage (160).

Figure 29-31 Bronchogenic cyst. High magnification. The lining epithelium is columnar, with a ciliated surface.

Thyroglossal duct cysts differ from bronchogenic cysts in that they do not contain smooth muscle and they frequently contain thyroid follicles (179).

Pathogenesis. On electron microscopy, the cilia show two central microtubules surrounded by nine paired microtubules (180).

CUTANEOUS CILIATED CYST

Clinical Summary. Cutaneous ciliated cysts are found very rarely in females as a single lesion, largely on the lower extremities, and even more rarely in males and on the back (181–184). They usually measure several centimeters in diameter. They are either unilocular or multilocular and are filled with clear or amber fluid. The finding of one on the perineum led the authors to suggest a primitive tailgut origin to this cyst, probably from the embryonic remnants of cloacal membrane (185).

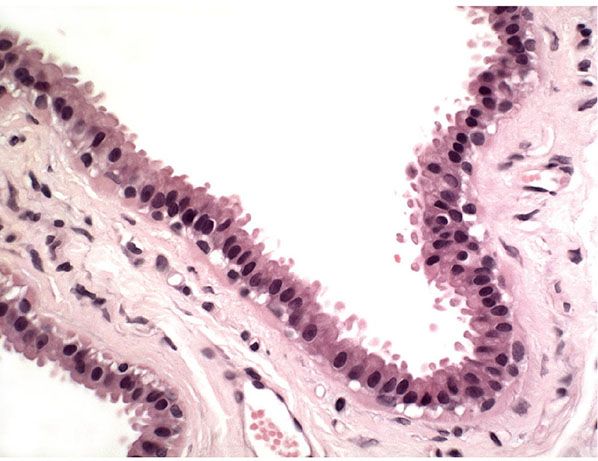

Histopathology. Cutaneous ciliated cysts show numerous papillary projections lined by a simple cuboidal or columnar ciliated epithelium. Mucin-secreting cells are absent (183).

Pathogenesis. The epithelial lining of the cysts resembles that seen in the fallopian tube. On electron microscopy, the cilia show two central filaments encircled by nine pairs of filaments (186).

MEDIAN RAPHE CYST OF THE PENIS

Clinical Summary. Median raphe cysts of the penis occur usually in young adults. They are located on the ventral aspect of the penis, most commonly on the glans. They are solitary and measure only a few millimeters in diameter (187). However, they may extend over several centimeters in a linear fashion (188). It seems that, in some instances, median raphe cysts have been erroneously reported as apocrine cystadenoma of the penis (Fig. 29-32; see also Chapter 31) (189,190).

Figure 29-32 Apocrine cyst. In this small dermal cyst, the lining epithelium forms a single layer with apocrine snouting secretion.

Histopathology. The cysts are lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium varying from one to four cells in thickness, mimicking the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Some of the epithelial cells have clear cytoplasm, mucin-containing cells are uncommon, and a case lined by ciliated epithelium has been described (191).

Pathogenesis. It is likely that median raphe cysts do not represent a defective closure of the median raphe but rather the anomalous budding and separation of urethral columnar epithelium from the urethra (192).

Principles of Management. This is a benign condition, and surgical treatment is considered only for symptomatic or cosmetic purposes.

ERUPTIVE VELLUS HAIR CYSTS

Clinical Summary. In eruptive vellus hair cysts, a condition first described in 1977 (193), asymptomatic follicular papules 1 to 2 mm in diameter occur, most commonly on the chest but in some instances elsewhere. Some of the papules have a crusted or umbilicated surface. The condition is usually seen in children and young adults but can develop at any age. Spontaneous clearing may take place in a few years. Autosomal dominant inheritance has been described (194,195). Cytokeratin studies have shown that epidermoid cysts expressed cytokeratin 10 and eruptive vellus hair cysts expressed cytokeratin 17, whereas trichilemmal cysts and steatocystoma multiplex showed expression of both cytokeratin 10 and cytokeratin 17, supporting the opinion that eruptive vellus hair cysts, which stained negative for cytokeratin 10, and steatocystoma multiplex are distinct entities and not variants of one disorder (196).

Histopathology. A cystic structure is usually seen in the mid-dermis lined by squamous epithelium. It contains laminated keratinous material and varying numbers of transversely and obliquely cut vellus hairs (193). In some cysts, vellus hairs are seen emerging from follicle-like invaginations of the cyst wall (197). In other cysts, a telogen hair follicle is seen extending from the lower surface toward the subcutis (193). Crusted or umbilicated lesions show either a cyst communicating with the surface and extruding its contents (195,198) or partial destruction of a cyst by a granulomatous infiltrate and elimination of vellus hairs to the surface of the skin (199).

Pathogenesis. Eruptive vellus hair cysts represent a developmental abnormality of vellus hair follicles that predisposes them to occlusion at their infundibular level. This results in retention of hairs, cystic dilation of the proximal part of the follicle, and secondary atrophy of the hair bulbs (193,198). There is a close relationship with steatocystoma multiplex (200). Both processes could be described as multiple pilosebaceous cysts (201).

WARTY DYSKERATOMA

Clinical Summary. Warty dyskeratoma, first described in 1957 (202), usually occurs as a solitary lesion, most commonly on the scalp, face, or neck, although a case with multiple lesions has been described (203). It has also been reported in non–sun-exposed skin, including the oral mucosa, usually on the hard palate or an alveolar ridge (204,205). Although its clinical appearance is not always distinctive, it often occurs as a slightly elevated papule or nodule with a keratotic umbilicated center (206). The lesion, after having reached a certain size, persists indefinitely.

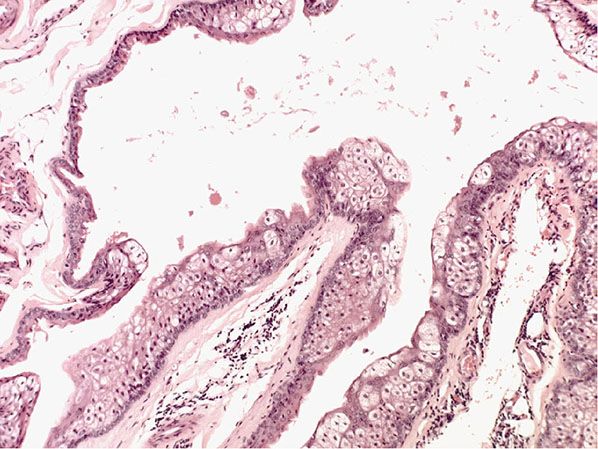

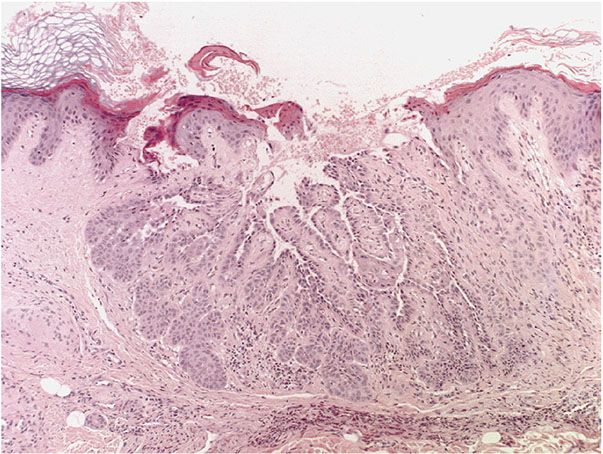

Histopathology. The center of the lesion is occupied by a large, cup-shaped invagination connected with the surface by a channel filled with keratinous material (Figs. 29-33 to 29-35). The large invagination contains numerous acantholytic, dyskeratotic cells in its upper portion. The lower portion of the invagination is occupied by numerous villi, that is, markedly elongated dermal papillae that are often lined with only a single layer of basal cells and project upward from the base of the cup-shaped invagination (Fig. 29-32) (202,207–209). Typical corps ronds can usually be seen in the thickened granular layer lining the channel at the entrance to the invagination (Figs. 29-34 and 29-35) (206,210).

Figure 29-33 Warty dyskeratoma. Low magnification. A large invagination is connected to the surface by a channel.

Figure 29-34 Warty dyskeratoma. The villi at the base of the invagination are covered with a single layer of cells. Acantholytic, dyskeratotic cells lie above the villi.

Figure 29-35 Warty dyskeratoma. High magnification. Acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells lie above the basal layer of epithelial cells.

Pathogenesis. The central cup-shaped invagination has been interpreted by several observers as a greatly dilated hair follicle because in early lesions a hair follicle or sebaceous gland is often connected with the invagination (207). Occasionally, two or three adjoining follicles seem to be involved (206). The fact, however, that warty dyskeratoma can arise on the oral mucosa indicates that, as in Darier disease, the dyskeratotic, acantholytic process is not always derived from a pilosebaceous structure.

Although attempts were made at first to correlate warty dyskeratoma with Darier disease, it is now generally agreed that warty dyskeratoma represents an entity—“a benign cutaneous tumor that resembles Darier disease microscopically” (202). Indeed, it has been proposed that the entity should be regarded as a benign follicular adnexal neoplasm and designated as “follicualr dyskeratoma” (211).

Principles of Management. This is a benign condition that does not require treatment. Surgical excision is performed for removal if desired or to obtain histologic diagnosis.

ACTINIC KERATOSIS (SOLAR KERATOSIS)

Clinical Summary. Solar keratoses are also known as actinic keratoses. The adjective solar is more specific because it refers to the sun as the cause, whereas the adjective actinic refers to a variety of rays (212). Even among the sun’s rays, action spectrum evaluations indicate that the ultraviolet B (UVB) rays (290 to 320 nm) are the most damaging (“carcinogenic”) rays, although UVA rays (320 to 400 nm) can augment the damaging effects of UVB rays (213).

Actinic keratoses are usually seen as multiple lesions in sun-exposed areas of the skin in persons in or past middle life who have fair complexions (Figs. 29-36 and 29-37). Excessive exposure to sunlight over many years and inadequate protection against it are the essential predisposing factors. Actinic keratoses are seen most commonly on the face and the dorsa of the hands and in the bald portions of the scalp in men (214).

Figure 29-36 Actinic keratosis. The lesion on the forehead is crusted and erythematous.

Figure 29-37 Actinic keratosis. Multiple lesions on this sun-damaged scalp.

Usually, the lesions measure less than 1 cm in diameter. They are erythematous, are often covered by adherent scales, and, except in their hypertrophic form, show little or no infiltration. Some actinic keratoses are pigmented and show peripheral spreading, making clinical differentiation from lentigo maligna difficult (215). Occasionally, lesions show marked hyperkeratosis and then have the clinical aspect of cutaneous horns. A lesion analogous to actinic keratosis occurs on the vermilion border of the lower lip as solar cheilitis and may show areas of erosion and hyperkeratosis (216–218).

Actinic keratosis and solar cheilitis can develop into an SCC. However, the incidence of this transformation is difficult to determine because the borderline between actinic keratosis and SCC is not clear-cut (see Histopathology). It has been estimated that in 20% of patients with actinic keratoses, SCC develops in one or more of the lesions (219). Usually, SCCs arising either in actinic keratoses or de novo in sun-damaged skin do not metastasize. The incidence of metastasis in different series varies from 0.5% (220) to 3% (221). In carcinoma of the vermilion border of the lip, however, metastases have been found in 11% of the cases (221).

Histopathology. Actinic keratoses are keratinocytic dysplasias or SCCs in situ. This definition is preferable to their designation as precancerous because most of them never progress to invasive cancers. Biologically, the lesions are still benign; invasion into the dermis, if present at all, is limited to the most superficial portion, the papillary dermis (see Differential Diagnosis) (222–235).

Five types of actinic keratosis can be recognized histologically: hypertrophic, atrophic, bowenoid, acantholytic, and pigmented (Figs. 29-38 to 29-47). Transitions and combinations among these five types occur. In addition, many cutaneous horns prove on histologic examination to be actinic keratoses.

Figure 29-38 Actinic keratosis. Tall columns of parakeratotic keratin alternate with bands of orthokeratotic keratin, with moderate atypia of the underlying keratinocytes.

Figure 29-39 Actinic keratosis. Beneath a thick layer of parakeratotic keratin, the epidermis shows cytologic atypia.

Figure 29-40 Actinic keratosis, hypertrophic type. The lesion shows hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis with prominent cytologic atypia. There is a moderate lymphocytic infiltrate in the underlying papillary dermis.

Figure 29-41 Bowenoid actinic keratosis. A crusted lesion on the ear helix.

Figure 29-42 Bowenoid actinic keratosis. Low magnification. Beneath a thick layer of parakeratotic keratin, the epidermis shows cytologic atypia.

Figure 29-43 Bowenoid actinic keratosis. Medium magnification. Marked cellular and nuclear pleomorphisms are present together with frequent and atypical mitoses in a bowenoid actinic keratosis (squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

Figure 29-44 Bowenoid actinic keratosis. High magnification. Large atypical mitoses are prominent in this bowenoid actinic keratosis.

Figure 29-45 Actinic keratosis, acantholytic type. Low magnification. The epidermis is markedly hyperkeratotic. In the dermis, there is a dense, lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate. The keratosis shows focal acantholytic change.

Figure 29-46 Actinic keratosis, acantholytic type. High magnification. Keratinocytes in the basal layer are crowded, with an increased nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio. They tend to become separated from one another and adopt a rounded configuration. This process of “secondary acantholysis” may in some instances result in the formation of pseudoglandular spaces that may mimic a glandular pattern of differentiation.

Figure 29-47 Cutaneous horn. The horn consists of a column of keratin arising on the sun-exposed skin of the ear.

In the hypertrophic type of actinic keratosis, hyperkeratosis is pronounced and is usually intermingled with areas of parakeratosis (222). This variety of keratosis, sometimes referred to as florid keratosis, may easily be overdiagnosed as invasive SCC by the unwary. Mild or moderate papillomatosis may be present. The epidermis is thickened in most areas and shows irregular downward proliferation that is limited to the uppermost dermis and does not represent frank invasion (Fig. 29-40). A varying proportion of the keratinocytes in the stratum malpighii show a loss of polarity and thus a disorderly arrangement. Some of these cells show pleomorphism and atypicality (“anaplasia”) of their nuclei, which appear large, irregular, and hyperchromatic. Often, the nuclei in the basal layer are closely crowded together. Some of the cells in the midportion of the epidermis show premature keratinization, resulting in dyskeratotic cells or apoptotic bodies characterized by homogeneous, eosinophilic cytoplasm with or without a nucleus. In contrast to the epidermal keratinocytes, the cells of the hair follicles and eccrine ducts that penetrate the epidermis within actinic keratoses retain their normal appearance and keratinize normally (223,224). Occasionally, cells of the normal adnexal epithelium extend over the atypical cells of the epidermis in an umbrella-like fashion. In these cases, the keratin overlying the hyperplastic adnexal epithelium may be orthokeratotic, resulting in a characteristic pattern of alternating hyperkeratosis (over the dysplastic clone of cells) and orthokeratosis. In some cases, abnormal keratinocytes extend downward on the outside of the follicular infundibulum to the level of the sebaceous duct and, less commonly, along the eccrine duct (224).

A variant of the hypertrophic type of actinic keratosis is the lichenoid actinic keratosis, which demonstrates nuclear atypia, irregular acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, the presence of basal cell liquefaction, degeneration of the basal cell layer, and a bandlike “lichenoid” infiltrate in close apposition to the epidermis (225). Fairly numerous eosinophilic, homogeneous apoptotic bodies are seen in the upper dermis as the so-called Civatte bodies. Aside from the presence of nuclear atypicality, there is considerable resemblance to lichen planus and benign lichenoid keratosis. An additional distinguishing feature may be the presence of plasma cells in the lichenoid infiltrate (see Chapter 7).

In rare instances of actinic keratosis of the hypertrophic type, in addition to finding anaplastic nuclei in the lower epidermis, one finds areas of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis in the upper epidermis. These changes are like those seen in bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, in linear epidermal nevus, and as incidental epidermolytic hyperkeratosis in a variety of lesions. In areas of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, one observes in the upper epidermis clear spaces around the nuclei and a thickened granular layer with large, irregularly shaped keratohyaline granules (44). Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may also occur in lesions of solar cheilitis (226).

In the atrophic type of actinic keratosis, hyperkeratosis usually is slight. The epidermis is thinned and devoid of rete ridges. Atypicality of the cells is found predominantly in the basal cell layer, which consists of cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei that lie close together. The atypical basal layer may proliferate into the dermis as buds and ductlike structures. It may also surround as cell mantles the upper portion of pilosebaceous follicles and sweat ducts, the epithelium of which otherwise appears normal (203).

The Bowenoid type of actinic keratosis is histologically indistinguishable from Bowen disease and may also be referred to as SCC in situ. As in Bowen disease, within the epidermis there is considerable disorder in the arrangement of the nuclei, as well as clumping of nuclei and dyskeratosis (Figs. 29-41 to 29-44).

In the acantholytic type of actinic keratosis, immediately above the atypical cells composing the basal cell layer there are clefts or lacunae similar to those seen in Darier disease (see Chapter 6) (227). These clefts form as a result of anaplastic changes in the lowermost epidermis, resulting in dyskeratosis and loss of the intercellular bridges (Fig. 29-45). A few acantholytic cells may be present within the clefts (Fig. 29-46). Because the acantholysis is preceded by cellular changes, it is referred to as secondary acantholysis, in contrast to the primary acantholysis seen in the “acantholytic” diseases, such as pemphigus vulgaris and Darier disease. Above the acantholytic clefts, the epidermis shows varying degrees of atypicality but generally less atypicality than is seen in the basal cell layer. The anaplastic cells of the basal cell layer frequently show extensions into the upper dermis as buds or short, ductlike structures. Suprabasal acantholysis may also be seen around hair follicles and sweat ducts in the upper dermis. When atypia is full thickness or high grade, the term acantholytic SCC in situ may be applied.

In the pigmented type of actinic keratosis, excessive amounts of melanin are present, especially in the basal cell layer. In some cases, the atypical keratinocytes are well melanized (228). In others, almost all of the melanin is retained within the cell bodies and dendrites of the melanocytes, indicating some block in melanin transfer. Numerous melanophages are seen in most cases in the superficial dermis (215).

In all five types of actinic keratosis, the upper dermis usually shows a fairly dense, chronic inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphoid cells but often also containing plasma cells. Solar cheilitis, more frequently than actinic keratosis of the skin, shows an inflammatory infiltrate in which plasma cells predominate (216). Although the upper dermis usually shows solar or basophilic degeneration, this may be absent in areas with a pronounced inflammatory reaction, probably because the inflammation has resulted in a regeneration of collagen.

In instances in which the histologic diagnosis is actinic keratosis but the clinical diagnosis is SCC, it is advisable to section more deeply into the block of tissue because progression into SCC may have taken place in another area. Because no sharp line of demarcation exists between the two conditions, it is not always possible to decide whether a lesion can still be regarded as actinic keratosis or should be classified as early SCC. Thus, some authors regard SCC as a lesion in which irregular aggregates of atypical keratinocytes are found in the papillary dermis, not in continuity with the overlying epidermis (229). Others call a lesion that does not extend downward to the level of the reticular dermis an actinic keratosis without qualification (229). This decision is rarely a vital one because early SCC arising in an actinic keratosis rarely causes metastases, although it may become deeply invasive and destructive through further growth. Because carcinomas arising in solar cheilitis have a significantly higher tendency to metastasize than carcinomas arising in actinic keratosis, and because invasion of the dermis in solar cheilitis may be focal, lesions of solar cheilitis require thorough examination by means of step sections (217).

Pathogenesis. On electron microscopic examination, only a difference in degree was found to exist between actinic keratosis and SCC (231). With the use of blood group antigens as indicators of malignancy to sections of actinic keratosis, areas of positive staining alternate with areas showing no staining, the lack of staining being indicative of anaplasia. Areas of irregular downward proliferation or early invasion are consistently negative (232).

Differential Diagnosis. In actinic keratoses showing relatively slight atypicality, or anaplasia, of the tumor cells, diagnosis may be difficult. Thus, a hypertrophic actinic keratosis with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate may show a close histologic resemblance to the lesion known as benign lichenoid keratosis. In fact, this lesion was at one time believed to be a variant of actinic keratosis (233). Benign lichenoid keratosis differs from actinic keratosis by showing dissolution rather than atypicality of the basal cell layer, analogous to lichen planus (see Chapter 7) (234,235).