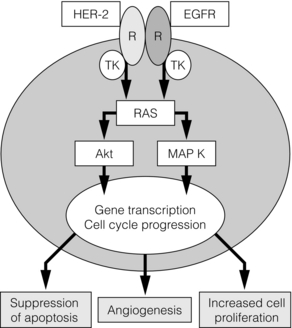

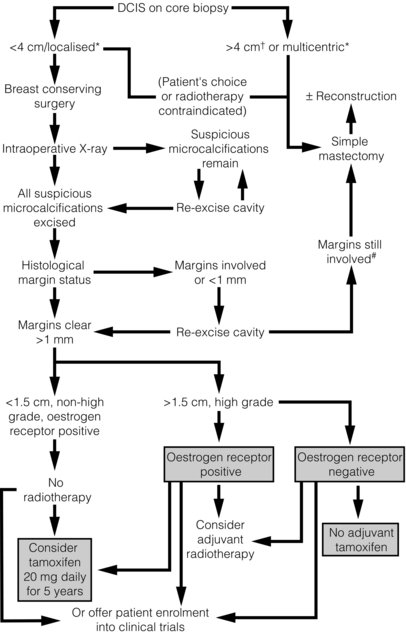

11 The introduction of screening mammography has resulted in a marked increase in the detection rates of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) from 2% of newly diagnosed breast cancers before national screening to 20% of all screen-detected tumours.1 DCIS is a preinvasive breast cancer; the proliferation of malignant ductal epithelial cells remains confined by an intact basement membrane, with no invasion into the surrounding stroma.2 Over 90% of DCIS lesions currently diagnosed are impalpable, asymptomatic and detected by screening. These screening-detected cases are frequently small (< 4 cm) and localised, and breast-conserving surgery is often possible. The remaining 10% present symptomatically, with a palpable breast lump, nipple discharge or Paget’s disease of the nipple. If these symptoms are present, the underlying disease is often extensive and usually requires mastectomy. Risk factors for the development of DCIS include a family history of breast cancer, older age at first childbirth and nulliparity.3 Although breast epithelial proliferation is increased by the use of the oral contraceptive pill4 and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), particularly combined oestrogen/progestogen HRT for over 5 years,5 there is little evidence to date that either the oral contraceptive pill or HRT increases the risk of DCIS.4 Two studies6,7 have reported a relative risk of 1.4 for the development of DCIS following oestrogen-only HRT preparations and a relative risk of 1.7–2.3 with oestrogen- and progestogen-containing preparations.8 In the Women’s Health Initiative study there were 47 cases of DCIS in the HRT group compared with 37 cases in the control group (hazard ratio 1.18; weighted P = 0.09). Other studies have shown no increased risk following HRT use.9,10 Although factors that pertain to an increased risk of developing DCIS have been identified, the natural history of this heterogeneous disease remains poorly understood. It is thought that developmental pathways for low- and intermediate-grade DCIS are distinct from the development of high-grade DCIS and can be explained partly by reference to biological markers. In the sequence of progression from normal breast to DCIS, there is a variable loss of chromosomal heterozygosity dependent on nuclear grade. Low- and intermediate-grade tumours show 16q loss, whereas there is 17q gain in high-grade lesions.11 It is likely that low-grade lesions arise from oestrogen receptor-positive atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) or lobular intra-epithelial neoplasia carcinoma and progress to low-grade oestrogen receptor-positive DCIS. High-grade lesions have no obvious precursor, unless they arise from usual ductal hyperplasia or ADH that expresses 17q gain. The progression of well-differentiated/low-grade DCIS to poorly differentiated/high-grade DCIS or high-grade invasive cancer is an uncommon event.12 Retrospective studies of low-grade DCIS misdiagnosed as benign conditions found that, 20 years after local excision, approximately 33% had developed an invasive cancer.14 As not all cases of DCIS progress to invasive disease, detection by mammographic screening may lead to over-treatment of ‘non-progressive DCIS’, i.e. DCIS that would not progress to invasive disease if left untreated. It was hoped that breast screening programmes would, after a lag phase, result in a decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer, secondary to an increase in detection and treatment of DCIS. This has not been demonstrated, as there has been no corresponding decrease in invasive disease in a recent review of American screening data although there appears to be a reduction in grade 3 cancers in women of screening age over time.15 There is therefore now concern that we may be over-treating DCIS and in particular ‘low-risk’ DCIS, and that such lesions may never pose a threat to a patient’s life. Suggestions for alternative management strategies for these patients range from endocrine therapy alone (no surgery)16 to, at the most extreme, ‘watchful waiting’.15 However, what constitutes ‘low-risk’ DCIS remains undefined. The recent MAP.3 trial showed that exemestane reduces DCIS development in a prevention setting.17 A study looking at ADH (which may be a precursor lesion of low-grade DCIS and has an approximately fivefold increase in risk of subsequent invasive cancer) showed that ADH (and by implication, low-grade DCIS) has become less common since women have stopped using as much HRT.18 The low-grade lesions are the ones that are being potentially over-treated. They are nearly always oestrogen dependent. Removing the oestrogenic drive, either following menopause or with the use of aromatase inhibitors, may allow control of these low-grade cases so they progress to invasive cancer only rarely. Recent evidence suggests that the breast has stem cells that can reconstitute the various cell types within the breast after trauma. Cancers (including DCIS) arise from accumulations of mutations within stem cells that disrupt their tightly controlled self-renewal and proliferation processes. Stem cells have recently been isolated from human DCIS. In this process, samples of human DCIS tissue have been separated into single cells and a subset of these cells (which are putative stem/progenitor cells) grows, in non-adherent culture conditions, to form three-dimensional branching structures (known as mammospheres). Mammosphere growth is dependent on growth simulation via the epidermal growth factor (EGF) and Notch receptor pathways.19 The DCIS stem cell paradigm could explain the development of both multifocal DCIS and local recurrence. Stem cells could potentially survive after wide local excision with clear margins and regrow, which would also explain the ‘identical’ receptor expression seen in recurrent DCIS as well as early recurrences seen most often in high-grade DCIS, as there are more stem cells found in these high-grade lesions. Potentially, therefore, targeted inhibition of stem cells could reduce the rate of DCIS recurrence. Non-comedo DCIS encompasses all other subtypes and includes the following types: • Solid – where tumour fills extended duct spaces. • Micropapillary – where tufts of cells project into the duct lumen perpendicular to the basement membrane. • Papillary – where the projecting tufts are larger than in the micropapillary type and contain a fibrovascular core. • Cribriform – where the tumour takes on a fenestrated/sieve-like appearance. • Clinging (flat) – where there are variable columnar cell alterations along the duct margins. (There remains controversy as to whether clinging DCIS is truly an in situ cancer or whether it should be considered as atypical hyperplasia rather than DCIS.) Rarer subtypes also exist, including neuroendocrine, encysted papillary, apocrine and signet cell. The UK- and EU-funded breast screening programmes classify DCIS as of low, intermediate and high nuclear grade. This definition is based on the characteristics of the lesion as seen with a high-power microscope lens (× 40) and uses a comparison of tumour cell size with normal epithelial and red blood cell size:20 • Low nuclear grade DCIS has evenly spaced cells with centrally placed small nuclei and few mitoses and nucleoli that are not easily seen. • High nuclear grade DCIS has pleomorphic irregularly spaced cells with large irregular nuclei (often three times the size of erythrocytes), prominent nucleoli and frequent mitoses. It is often solid with comedo necrosis and calcification. • Intermediate-grade DCIS has features between those seen in low- and high-grade DCIS. Most cases of DCIS are unicentric.21 Following extensive pathological sectioning of DCIS mastectomy specimens, only 1% show multicentric disease.21 A multicentric tumour is defined as separate foci of tumour found in more than one breast quadrant, or more than 5 cm away from the initial primary. A tumour is classified as multifocal if there are separate tumour foci in the same quadrant that are close to each other, although most such lesions have similar morphology and are linked.22 The local spread of DCIS is along branching ducts that form the glandular breast. The ducts, which are ill defined, often extend beyond the borders of a quadrant. Most DCIS is continuous along the branching ductal network. Poorly differentiated high-grade lesions are reported to be more frequently multifocal.23 Most DCIS recurrences are at or near the site of the initial tumour,24 but some recurrences are remote from the initial lesion yet exhibit similar genotypical and phenotypical characteristics to the primary lesion.12 As well as documenting pathological type and grade on the histology report, the pathologist should detail the presence or absence of microinvasion. If microinvasion is detected histologically, a thorough examination of the entire specimen should be undertaken to exclude other previously unnoticed areas of invasive cancer. Lesions that can be mistaken for microinvasion include DCIS involving lobules, branching of ducts, distortion of ducts by acini or fibrosis, crush or cautery artefacts, and DCIS involving a benign sclerosing process (e.g. radial scar).25–29 The current classification combines lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) into a single entity known as lobular intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN). Rather than a premalignant lesion, LIN is considered a marker of increased risk. It is often an incidental finding during breast biopsy and accounts for approximately 0.5% of symptomatic and 1% of screen-detected tumours. In situ ductal and lobular tumours show different pathological and clinical features. Compared with DCIS, patients developing LIN tend to be younger and premenopausal, and have bilateral and multicentric disease of lower grade and close to 100% oestrogen receptor expression (Table 11.1). There is an approximate eight- to ninefold increased risk of developing invasive carcinoma after a diagnosis of LCIS compared to the general population.30 Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish histologically between LCIS and DCIS, and the pathology report should state this. The clinical interpretation of the report should take into account the increased risks from both tumour subtypes. Table 11.1 Comparative clinicopathological features of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and tabular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) If LIN is detected at core biopsy, the area of suspicion is usually excised to confirm the diagnosis and exclude an adjacent invasive focus. If LIN is diagnosed coincidentally following excision of a coexisting lesion, no further surgical treatment is necessary (even if the area of lobular neoplasia is not fully excised) and the patient should undergo regular review on a ‘watch and wait’ basis or be considered for a preventional strategy. The NSABP P-1 prevention trial showed a 56% reduction in the risk of developing subsequent invasive cancer in women with LCIS who received tamoxifen.31 Further studies are ongoing with aromatase inhibitors in postmenopausal patients with LIN. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy have no place in the treatment of lobular neoplasia. A problem area is pleomorphic LCIS. The current perspective is that this should be treated like DCIS rather than lobular neoplasia but the scientific basis for this is minimal. Further studies and clarification of the behaviour and most appropriate treatment of pleomorphic LCIS is needed urgently. To advance our understanding of the development and behaviour of DCIS, there has been interest in cell receptor expression and signalling pathways controlling growth. These studies have been mainly based on immunohistochemical assessment and show that poorly differentiated high-grade comedo DCIS has low oestrogen receptor expression, high rates of cell proliferation32 (as expressed by Ki67, a nuclear antigen expressed in late G1 S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle but not in the quiescent G0),33 high rates of apoptosis,34 and over-expression of HER-2 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR (HER-1)).32 Low-grade lesions in contrast have high oestrogen receptor expression, with lower rates of cell proliferation32 and apoptosis than high-grade lesions,34 and they rarely overexpress HER-2.32 Progesterone receptor expression correlates with oestrogen receptor expression in both low- and high-grade tumours.32 In comparison, normal breast epithelium has low levels of expression of oestrogen receptor and progesterone receptor,35 and a very low rate of apoptosis and HER-2 expression. The increased rate of apoptosis seen in DCIS is lost on progression to invasive cancer, but the high proliferative rate is maintained.36 Cyclin D1, an oncogene responsible for G1 cell cycle proliferation/progression and induction of apoptosis, is overexpressed in approximately 90% of in situ and invasive ductal cancers.37 It also appears to be associated with a loss of differentiation (measured by p27Kip1).38 In oestrogen receptor-positive tumours, the driving force behind this increase in cell proliferation is the nuclear action of the activated oestrogen receptor, which increases growth-promoting gene transcription. In oestrogen receptor-negative DCIS, the driving pathway is thought to be predominantly via EGFR/HER-2/RAS/MAP kinase activation (Fig. 11.1). This leads to a subsequent increase in transcription of both proliferative and, via Akt, anti-apoptotic genes. Activation of this pathway also induces the expression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2), which is an inducible enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandins. It has been found to be overexpressed in up to 80% of DCIS.39 COX-2-positive DCIS shows increased cell proliferation, and is related to increased tumour recurrence and decreased survival in invasive cancer.40 Figure 11.1 The basic growth pathway in oestrogen receptor-negative breast tumour cells. The oestrogen receptor-positive signalling pathway is mediated via oestrogen attaching to its receptor, which then moves down its concentration gradient to the cell nucleus. The presence of oestrogen receptor in the cell nucleus subsequently increases gene transcription and expression of growth-promoting factors, leading to increased cell proliferation and tumour growth. In cells that do not express oestrogen receptors, the main signalling pathway for growth is via the epidermal growth factor (EGF)/c-erbB-2 receptor; this activates the RAS intracellular messenger, which increases cell proliferation and tumour growth via MAP kinase. RAS stimulation also leads to the suppression of the apoptosis cascade via Akt and BAD phosphorylation (an apoptotic protein). MAP K, MAP kinase; R, receptor; TK, tyrosine kinase. In addition to alterations in cell proliferation and apoptosis, the development of neovascularisation is necessary for the growth of solid tumours. It is driven in part by angiogenic factors expressed in hypoxic areas of the tumour. Hypoxic areas of DCIS show a less well differentiated, more malignant phenotype, with increased HIF-1α (a hypoxia-induced transcription factor), decreased oestrogen receptor expression and increased expression of cytokeratin-19 (a breast stem cell marker).27 It is felt that hypoxia-induced dedifferentiation could be a factor promoting tumour progression.41 Over 90% of DCIS is detected by mammographic screening. Approximately 70% of these mammographically detected cases present as microcalcifications with no associated mass lesion. Calcifications may be heterogeneous, fine, linear, branching, malignant or of indeterminate appearance. Microcalcifications with an associated mass lesion are seen in approximately 30% of DCIS diagnosed by screening.42 Circumscribed nodules, ill-defined masses, duct asymmetry and architectural distortion are sometimes seen in association with DCIS.43 When diagnosed clinically, DCIS is often extensive or associated with a concurrent invasive tumour. It may present as a palpable mass, Paget’s disease of the nipple or nipple discharge.44 In the NHS Breast Screening Programme, the primary method of diagnosis was formerly by stereotactic core biopsy with a 14 G needle. If image-guided core biopsy was inconclusive then vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) using a device such as a Mammotome, which takes several contiguous biopsies of a wider calibre (11 G) during a single pass, can be used. A metal clip can be inserted during the procedure to aid future localisation. VAB has a higher sensitivity and specificity than core biopsy and is now the biopsy technique of choice for microcalcification,45 but still underdiagnoses a coexisting invasive tumour in 10–20% of cases due to sampling error.46 Other factors that have been shown to underestimate the presence of associated invasive disease include high-grade lesions, imaging size > 2 cm, Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 or 5, a visable mass at mammography (versus only calcification) and a palpable abnormality.45 If the area of DCIS is extensive (> 4 cm in size), two or more areas should be biopsied preoperatively to increase the chance of detecting any associated invasive component. If a definitive histological diagnosis cannot be made with core biopsy or VAB, this due to failure to sample the calcification adequately, or doubt exists as to whether DCIS is present on histology, then open biopsy is necessary (see Chapter 1). The excised specimen should be sent for immediate radiography, after careful orientation with Liga-clips or metal markers, to confirm that all microcalcification of concern has been excised and is clear of margins. The guidelines of the Association of Breast Surgeons at BASO47 recommends that 90% of diagnostic guided biopsies for screen-detected abnormalities should weigh less than 20 g. Due to improved preoperative diagnosis, wire-guided localisation procedures are usually therapeutic rather than diagnostic. However, DCIS is often pathologically larger than mammographically suggested; this is especially true if magnification views are not used, and up to 30% of cases need re-excision to clear margins adequately.48 Accurate orientation of the specimen is essential to direct re-excision of the relevant margins and to minimise the volume of any re-excision. Ductoscopy: Ductoscopy (see Chapter 3) is an appealing option for DCIS. There has been interest in its use both in diagnosis and potential for treatment with direct instillation of chemotherapy into the ducts49 (see Chapter 3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI can be used to image DCIS and is currently being investigated in a number of trials. DCIS may identify occult multifocal or contralateral disease, but there are concerns about the potential of MRI to overestimate the extent of disease, leading to wider than necessary excisions, and unnecessary mastectomy or identifying high numbers of contralateral lesions that turn out to be benign. There are also concerns that MRI might detect biologically insignificant disease that could increase ‘over-treatment’. It therefore remains under investigation in trials and has no routine role in assessing DCIS. The long-term recurrence rate following mastectomy for DCIS is less than 1%.50 As current evidence (see p. 181) points to DCIS being predominantly unicentric in origin, it is now recognised that mastectomy is over-treatment for the majority of patients.50 In 1983 mastectomy was performed for 71% of cases of DCIS in the USA but this had dropped to 44% by 1992.51 Mastectomy is now reserved for patients with larger areas of DCIS (arbitrarily considered as > 4 cm), for multicentric disease and for patients where radiotherapy is contraindicated. Women should also be offered mastectomy if the excision margins are involved following breast-conserving surgery and the patient is not deemed suitable for re-excision. Rates of re-excision versus mastectomy vary widely in different units. Women with DCIS requiring mastectomy are excellent candidates for skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. The recommended treatment protocol for DCIS is shown in Fig. 11.2. Figure 11.2 Recommended treatment algorithm for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). *Determined mammographically. Shaded boxes indicate those treatments suggested by the results of recent trials.55,66 †Areas of DCIS > 4 cm can be treated by breast conservation if unifocal and patient has large breasts, or is suitable for an oncoplastic procedure. #A further re-excision can be attempted providing the final cosmetic result is acceptable to the patient. The incidence of macroscopic lymph node metastasis in DCIS is less than 1% and should prompt thorough pathological examination for occult invasion. Formal axillary staging in women with DCIS should not be performed alongside breast-conserving surgery.52 However, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that a sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed at the same time as mastectomy for DCIS52 and women should be counselled as to the indications for this. The rationale for performing sentinel lymph node biopsy with mastectomy is the potential of occult invasive disease that may be identified histologically in a large area of DCIS. This would subsequently require axillary staging. A sentinel lymph node biopsy cannot easily be performed after a mastectomy. Patients found to have positive lymph nodes have occult invasive disease and should be managed accordingly. A study by Veronesi et al. of 508 patients with pure DCIS found that nine patients (1.8%) had epithelial cells found in the sentinel node (five of these nine cases were micrometastases alone). None of the cases showed further lymph node involvement at formal axillary dissection.53 A further study that looked retrospectively at the NSABP B-17 and B-24 data, from patients who had undergone local excision of DCIS with clear margins (no axillary surgery at initial treatment), showed that the ipsilateral nodal recurrence rate was 0.83 per 1000 patient-years in the B-17 trial and 0.36 per 1000 patient-years in the B-24 trial. Meta-analysis of the published literature showed approximately 1.8% of DCIS (almost entirely G3 or high-grade disease) had involved sentinel nodes.54 No trial has specifically evaluated breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy in DCIS. The long-term recurrence rate following mastectomy is known to be very low at less than 1%.50 The majority of these recurrences are invasive disease. This reflects the fact that after mastectomy no imaging is performed routinely of the ipsilateral side and further disease is only detected when it becomes clinically apparent – at which stage it is most likely to be invasive. The recurrence rate for breast-conserving surgery alone has been reported to be up to 25% at 8 years follow-up, with up to 50% of recurrences (i.e. 12.5% of all cases) being invasive disease.13,48,55

Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ

Background

Risk factors, natural history, pathology and receptors

Natural history

Stem cells

Pathology

Lobular intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN)

Clinicopathological feature

DCIS

LCIS

Age at diagnosis (years)

54–58

44–47

Premenopausal

30%

70%

Absence of clinical signs

90%

99%

Mammographic findings

Microcalcifications

None

Multicentric disease

30%

90%

Bilateral disease

12–20%

90%

Histological grade

65% high grade

90% low grade

Oestrogen receptor status

65% positive

95% positive

Subsequent invasive disease

30–40%

25–30%

Ipsilateral–contralateral ratio

9:1

1:1

Receptors and markers

Presentation, investigation and diagnosis

Investigation and diagnosis

Stereotactic core biopsy and vacuum-assisted biopsy

Localisation-guided biopsy

Other diagnostic procedures

Treatment: mastectomy versus breast-conserving surgery

Mastectomy

Breast-conserving surgery

Axillary staging

Recurrence: rates and predictors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine