IN THIS CHAPTER

- •

Introduction 141

- •

Surgical approach 142

- •

Reconstruction 150

- •

Umbilical stenosis 151

- •

Umbilical flattening 152

- •

Umbilical delay 152

The umbilicus is an aesthetically important component of the abdomen. Extra care should be taken in planning and executing the release and inset of the umbilicus during abdominoplasty procedures to provide the best result possible. The size, shape, contour, position, and appearance of the umbilicus and umbilical scars should be carefully planned to optimize the final aesthetic appearance of the umbilicus.

Introduction

The umbilicus is the central focus of the abdomen and an important aesthetic component of the body. It has been represented throughout history and across cultures as a sign of youth and beauty. The eye is naturally drawn to this point of the abdomen, which makes the appearance and location of the umbilicus critical. As such, an aesthetically pleasing umbilicus is necessary for an attractive abdomen, and vice versa. Far too often, great effort is made to keep the abdominoplasty incisions hidden only to have an umbilicus that is left unrejuvenated, with poor visible scars, or with a displeasing shape.

In order to create an aesthetically pleasing umbilicus one must first identify the characteristics that define it ( Table 12.1 ). Despite anatomical variability among patients, as well as particular surgeon and patient preference, there is a general consensus as to the characteristics that add to the aesthetic beauty of an umbilicus as well as those that detract from it. The vertical position of the umbilicus, the amount of depression compared to the periumbilical soft tissue, and the shape and size of the umbilicus should all be taken into account in abdominal contouring surgery.

| Small is preferable to large |

| A vertical ellipse is preferable to a circle |

| An ‘inny’ is more desirable than an ‘outie’ |

The vertical position of the umbilicus varies according to the length of the patient’s torso and the degree of soft-tissue laxity associated with aging and weight loss. An aesthetically pleasing umbilicus should have a shape that is vertically oriented and located in the midline, just cephalad to an imaginary line connecting the superiormost portions of the iliac crests. That said, in traditional abdominoplasty procedures, where the umbilicus is released from the surrounding soft tissue and inset into the abdominal flap, there is only a limited ability to change the vertical position of the umbilicus. This small variation is determined largely by the length of the umbilical stalk. As most abdominoplasty procedures involve some form of myofascial plication, the umbilical stalk is usually shortened and the variability in the vertical position of the umbilical inset is further reduced, essentially making it a relatively fixed position. Attempting to inset the umbilicus at a point much further cephalad or caudal from this will result in an unnatural shape and appearance and potentially lead to poor healing.

The umbilicus can present with a diverse variety of shapes and sizes in the body contouring population. Many factors combine to create each individual umbilical shape, including skin quality, soft-tissue laxity, body type, weight gain and loss, amount of adiposity, age, previous surgery/trauma, and genetics. Despite this variety, there are general characteristics of umbilical size, shape, and periumbilical contour that are more consistent with youth and beauty.

The youthful umbilicus is often vertically oval or jewel-shaped ( Fig. 12.1 ). The ideal size should match the patient’s body and preference, and therefore an exact measurement cannot be used for all patients. However, when the opportunity allows, it is better to err on the small side since, as aging and weight fluctuation usually result in an umbilicus that appears wider and larger than desired. A smaller umbilicus is usually judged to be more youthful in appearance.

A woman with a thin, toned abdomen usually presents with an umbilicus that also has a mild amount of superior hooding and a faint but appreciable depression or ‘washout’ area at the inferior pole ( Fig. 12.2 ). The superior hooding is largely a result of gravity pulling inferiorly on the upper skin and soft tissue when the patient is standing, leading to gathering of the skin and soft tissue at the superior portion of the umbilicus, which is firmly anchored by its stalk. This can easily be verified when patients are placed supine with a little Trendelenburg position. With reversal of the direction of the pull of gravity on the abdominal skin and soft tissue, the superior hooding is reduced or eliminated and inferior umbilical hooding becomes evident.

Introduction

The umbilicus is the central focus of the abdomen and an important aesthetic component of the body. It has been represented throughout history and across cultures as a sign of youth and beauty. The eye is naturally drawn to this point of the abdomen, which makes the appearance and location of the umbilicus critical. As such, an aesthetically pleasing umbilicus is necessary for an attractive abdomen, and vice versa. Far too often, great effort is made to keep the abdominoplasty incisions hidden only to have an umbilicus that is left unrejuvenated, with poor visible scars, or with a displeasing shape.

In order to create an aesthetically pleasing umbilicus one must first identify the characteristics that define it ( Table 12.1 ). Despite anatomical variability among patients, as well as particular surgeon and patient preference, there is a general consensus as to the characteristics that add to the aesthetic beauty of an umbilicus as well as those that detract from it. The vertical position of the umbilicus, the amount of depression compared to the periumbilical soft tissue, and the shape and size of the umbilicus should all be taken into account in abdominal contouring surgery.

| Small is preferable to large |

| A vertical ellipse is preferable to a circle |

| An ‘inny’ is more desirable than an ‘outie’ |

The vertical position of the umbilicus varies according to the length of the patient’s torso and the degree of soft-tissue laxity associated with aging and weight loss. An aesthetically pleasing umbilicus should have a shape that is vertically oriented and located in the midline, just cephalad to an imaginary line connecting the superiormost portions of the iliac crests. That said, in traditional abdominoplasty procedures, where the umbilicus is released from the surrounding soft tissue and inset into the abdominal flap, there is only a limited ability to change the vertical position of the umbilicus. This small variation is determined largely by the length of the umbilical stalk. As most abdominoplasty procedures involve some form of myofascial plication, the umbilical stalk is usually shortened and the variability in the vertical position of the umbilical inset is further reduced, essentially making it a relatively fixed position. Attempting to inset the umbilicus at a point much further cephalad or caudal from this will result in an unnatural shape and appearance and potentially lead to poor healing.

The umbilicus can present with a diverse variety of shapes and sizes in the body contouring population. Many factors combine to create each individual umbilical shape, including skin quality, soft-tissue laxity, body type, weight gain and loss, amount of adiposity, age, previous surgery/trauma, and genetics. Despite this variety, there are general characteristics of umbilical size, shape, and periumbilical contour that are more consistent with youth and beauty.

The youthful umbilicus is often vertically oval or jewel-shaped ( Fig. 12.1 ). The ideal size should match the patient’s body and preference, and therefore an exact measurement cannot be used for all patients. However, when the opportunity allows, it is better to err on the small side since, as aging and weight fluctuation usually result in an umbilicus that appears wider and larger than desired. A smaller umbilicus is usually judged to be more youthful in appearance.

A woman with a thin, toned abdomen usually presents with an umbilicus that also has a mild amount of superior hooding and a faint but appreciable depression or ‘washout’ area at the inferior pole ( Fig. 12.2 ). The superior hooding is largely a result of gravity pulling inferiorly on the upper skin and soft tissue when the patient is standing, leading to gathering of the skin and soft tissue at the superior portion of the umbilicus, which is firmly anchored by its stalk. This can easily be verified when patients are placed supine with a little Trendelenburg position. With reversal of the direction of the pull of gravity on the abdominal skin and soft tissue, the superior hooding is reduced or eliminated and inferior umbilical hooding becomes evident.

Surgical Approach ( Box 12.1 )

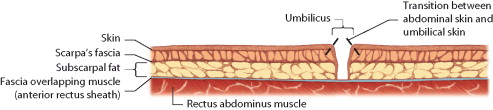

The umbilicus can be released in various ways, depending on surgeon preference and patient needs. The goal of release is to create a symmetric cutaneous component and to release it from the surrounding tissue in a manner that protects the blood supply but does not leave a large amount of excess adipose tissue. The size of the cutaneous component created when the umbilicus is released can be varied to suit the patient. Often, there is a transition zone where the umbilical skin becomes the abdominal skin, in a dorsoventral direction from the umbilicus to the coronal plane of the abdominal skin ( Fig. 12.3 ).

- •

The skin of the umbilicus should be released at the junction of the umbilicus with the abdominal skin

- •

The use of skin hooks and a number 11 blade facilitates skin incision

- •

Dissection down to the anterior rectus sheath is performed sharply with scissors

- •

The remainder of the umbilical release is performed with electrocautery after the lower abdominal flap is transected

The skin incision can be marked, or the umbilical opening can be placed on stretch using skin hooks to create the folds delineating the area to be incised ( Fig. 12.4 ). Using a methylene blue tattoo placed at the 12 o’clock position will identify this location during insetting ( Fig. 12.5 ). The incision can be made with either a number 15 or a number 11 scalpel. The number 11 is best used via a pushing motion ( Fig. 12.6 ). Once the skin has been incised, curved Metzenbaum scissors are used to sharply release the soft tissue around the umbilicus down to the deep fascia ( Fig. 12.7 ). The periumbilical perforators are usually within a centimeter or so from the umbilical stalk, so scissor dissection is performed down to the abdominal wall fascia near the stalk ( Fig. 12.8 ). The remainder of the periumbilical soft-tissue release is performed with electrocautery under direct vision once the abdominal soft-tissue apron inferior to the umbilicus has been transected ( Fig. 12.9 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree