Fig. 35.1

(a) Gastric bypass. (b) Sleeve gastrectomy. (c) Adjustable gastric band. (d) Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

General Considerations

In current bariatric surgical practices, the potential assistive role of upper endoscopy occurs on a daily basis. Although colonic pathology exists in bariatric patients as it does in the general population, this chapter will focus on the role of endoscopy involving bariatric surgical anatomy of the foregut. The role of endoscopy in bariatric surgery begins well before a patient undergoes an index surgical procedure. Four roles of upper endoscopy in the care of the bariatric surgical patient will be discussed here:

1.

Preoperative

2.

Intraoperative

3.

Postoperative

4.

Forensic endoscopy

Emerging roles for flexible endoscopy in the development of new bariatric surgical approaches will also be addressed.

Preprocedure Setup and Upper Endoscopy Technique

Patient positioning and room setup vary according to the needs of the particular procedure being performed. Complex revisional endoscopic procedures often require general anesthesia and may be performed in a formal operative theater. Most endoscopic suites, however, are appropriate for the majority of preoperative and postoperative diagnostic and minor therapeutic interventions.

The standard protocol requires that the patient is monitored appropriately for conscious sedation including electrocardiogram monitor, blood pressure and heart rate, and oxygen saturation. Some endoscopists utilize topical anesthetics in the posterior hypopharynx prior to initiating sedation. Under conscious sedation most procedures are performed with the patient in a left lateral position with head support to allow airway structures to shift forward, thus providing minimal resistance when accessing the hypopharynx and esophageal orifice. This position also allows for improved suctioning of airway and gastrointestinal secretions as well as quick removal of any regurgitated material to avoid potential aspiration. When endoscopy is performed under general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient’s airway is better protected and the patient may be in supine position and the endoscopist may stay above the head in the case of intraoperative endoscopy or on the left side as needed for optimized ergonomics while performing specific procedures. The nursing team assists with monitoring and medication administration and a technician is present to watch for equipment issues or assist with minor procedures such as biopsy collection, dilation, and other interventions.

When performing endoscopy in the bariatric patient, one must be especially cautious if this is done under conscious sedation. Obstructive sleep apnea in a bariatric patient can lead to apnea with low doses of sedative medication. Careful and slow titration of these medications is recommended. Availability of opiate and benzodiazepine reversal agents is essential. Avoidance of other sedating medications, such as somnolence inducing antihistamines, is advised since an antidote is not readily available.

Awake small caliber transnasal endoscopy is one potential solution for patients who are at high risk while undergoing sedation. Two clinical trials are pending, which will assess the feasibility of in-office awake transnasal endoscopy to assess surgical anatomy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. This may offer a cost and logistically efficient method for endoscopically assessing potential bariatric surgical patients with and without gastrointestinal symptoms.

History and physical examination prior to sedation helps to identify potentially unforeseen factors that may increase sedative risks. Comorbidities and medications are considered when deciding upon the sedation regimen, identifying potential drug interactions or conditions that may affect the drug metabolism or excretion. In bariatric endoscopy, most procedures are done in the endoscopy suite under moderate sedation. In this setting, the patient is able to respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by tactile stimulation. No interventions should be required to maintain the airway, and patients should maintain spontaneous ventilation. For more advanced procedures, or those with anticipated longer intervention times, or in those patients with very high sedation medication requirements, it is optimal to perform these in the operative theater under general anesthesia.

When introducing the endoscope, the most common technique used is the direct vision introduction. The scope is advanced over the tongue to visualize the vocal cords flexing the tip slightly. There is a crease of mucosal tissue formed by the ridge of tissue beneath the cords. Gentle pressure on this spot, asking the patient to swallow if under sedation, or having the anesthesiologist perform a jaw thrust if the patient is under general anesthesia facilitates the passage of the scope [2].

Preoperative Endoscopy

After undergoing index malabsorptive procedures such as the gastric bypass or the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, the remnant stomach and/or duodenum is not easily accessible from a standard transoral endoscopic approach. With the exception of technically challenging small bowel enteroscopy to course through the Roux limb, across the intestinal anastomosis, and back up the bypassed intestinal segment, standard endoscopic approaches to the biliopancreatic tree are not feasible. For this reason, it is suggested that preoperative upper endoscopy be performed in all patients undergoing these procedures if there is any potential concern for pathology in this region. This includes patients that have unexplained iron deficiency, suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding, or suspected Helicobacter pylori infection [3]. The observance of a previously undetected hiatal hernia with associated Cameron’s ulcers and resultant anemia will prompt the bariatric surgeon to counsel the patient appropriately for hernia repair prior to or during the proposed bariatric surgery. Helicobacter pylori infection has been associated with postoperative marginal ulcers, but positive routine testing does not necessarily require endoscopy unless the patient is symptomatic [4]. In the case of gastroesophageal reflux disease, if symptoms have not resolved or progress after appropriate medical therapy, upper endoscopy should be strongly considered [3]. Since only 3–5 % of asymptomatic patients undergo a change in surgical planning when endoscopy is routinely performed, many surgeons are proponents of selective preoperative endoscopy [5, 6]. The most frequent change in management is simply a delay in surgery until the abnormal finding can be clarified; a radical change in surgical approach is rarely the scenario. Due to logistics and costs involved with preoperative screening endoscopy and the relative rarity of significant findings, surgeons must decide for each patient what criteria necessitates additional preoperative endoscopic workup to optimize surgical planning.

Intraoperative Endoscopy

The use of intraoperative upper endoscopy during bariatric surgical procedures offers diagnostic as well as therapeutic options. While performing bariatric surgical procedures, intraoperative endoscopy can be used to assess staple line integrity during gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; it can serve to calibrate sleeve gastrectomy diameter and can confirm appropriate band positioning during gastric band placement procedures.

Intraoperative Leaks and Hemorrhage

During resectional procedures, endoscopy allows for visualization of staple lines to assess for bleeding or leakage. An endoscopic air leak test with an anastomotic or sleeve staple line submerged under saline can identify leaks in many cases. This method of leak testing has been found superior to methylene blue infusion via an orogastric tube with laparoscopic visualization [7]. Haddad et al. reviewed 2,311 gastric bypass cases at their institution from 2002 to 2011, in which 2,308 (99.9 %) successfully underwent intraoperative upper endoscopy to assess the gastrojejunostomy; 46 (2 %) clinically significant leaks were noted and received immediate intraoperative surgical repair. Forty-four required no additional intervention and two of the 46 initial leaks recurred and required additional treatment postoperatively. Twenty-five (1.1 %) patients developed early strictures, which were detected and treated with endoscopic dilation within 90 days of the index operation. No major complications occurred as a result of the endoscopies [8].

In addition to leaks, intraoperative and early postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage can be detected and treated endoscopically. Clinically relevant endolumenal bleeding occurs in 1–4 % of patients undergoing gastric bypass. Hematemesis and hematochezia are common presenting signs. Although some bleeding occurs from sites inaccessible to upper endoscopy requiring conservative or reconstructive approaches, when the bleeding originates from an accessible single staple line, an anastomotic staple line, or postoperatively from marginal ulcers, treatment can be accomplished utilizing endoscopic hemostatic injection or clip application in addition to guidance for laparoscopic oversewing of the suspect area. Energy sources are generally avoided to prevent delayed thermal injury and perforation. When the hemorrhage originates from bypassed gastrointestinal segments, inaccessibility of the bypassed anatomy adds additional diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The threshold for operative intervention is lower and remnant gastrectomy may be necessary to remove the entire source. Therapeutic endoscopy for gastrointestinal bleeding is optimally performed in an operative theater under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation to reduce the risk of aspiration as well as to allow for prompt formal operative intervention if necessary. Hemorrhage originating from a marginal ulcer can be addressed in a similar fashion as peptic ulcers utilizing the techniques described previously. Complications of therapeutic intervention for bleeding include those related to airway management, aspiration, and pulmonary complications. Obtaining hemodynamic stability is imperative prior to proceeding with a minimally invasive approach, such as therapeutic endoscopy, and blood products should be immediately available. Awareness that rebleeding occurs in up to 50 % of cases when a blood vessel is visible is important and surveillance endoscopy prior to patient discharge may be useful in preventing urgent repeat endoscopy thereafter in those patients [2, 9].

The endoscopic techniques described previously for gastric bypass are also applicable in treating complications of the single staple line of the gastric sleeve as well as the multiple staple lines of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.

Sleeve Calibration

In some circumstances, the endoscope can serve as a calibration tool during bariatric surgery. Sleeve gastrectomy is often performed with a transorally placed bougie of 32–38 French diameter to calibrate the diameter of the gastrectomized stomach and guide stapler placement. A 10–12 mm outside diameter (31.4–37.7 French) endoscope can also be used to calibrate a sleeve gastrectomy in place of a bougie. This technique potentially reduces the risk of esophageal injury during insertion of the bougie through direct visualization [10]. Reduced visceral trauma is also appreciated as the endoscope is introduced a single time to serve in the role of sleeve calibration as well as intraoperative inspection of the sleeve staple line.

Postoperative Endoscopy

The presence of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms after bariatric surgery and the management of surgical complications are the most common indications for postoperative endoscopy. Often these symptoms present in the first six postoperative months. These include abdominal pain, unrelenting nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, heartburn, regurgitation, diarrhea, bleeding, anemia, and weight regain. Complications of diagnostic endoscopy are rare (0.4 %) and most commonly involve those related to conscious sedation [2]. These include phlebitis, hypoxemia, hypoventilation, airway obstruction, hypotension, vasovagal episodes, arrhythmias, and aspiration [11]. Patients who are at higher risk for these complications include the elderly, patients with pulmonary compromise, and those with sleep apnea. Bleeding, infection, and reaction to medications are reported in less than 1 % of cases and perforation is exceedingly rare.

The goal of short-term postoperative endoscopy is to assess for structural pathology, such as ulcers or strictures. The most common diagnoses found with upper endoscopy after bariatric surgery are marginal ulcer, anastomotic stricture, staple line dehiscence, band erosion or slippage, gastroesophageal reflux sequelae, and choledocholithiasis [3]. Esophageal dilatation is frequently detected after gastric band, most commonly occurring because of chronic obstruction. Gastric outlet obstruction can be encountered secondary to anastomotic stenosis following bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch and structural kink following sleeve gastrectomy or due to a slipped gastric band.

The etiology of each of these conditions is multifactorial, including local tissue ischemia, anastomotic tension, technical error, and noncompliance with postoperative dietary and lifestyle modifications.

Marginal Ulcer

Marginal ulcers typically present as severe epigastric discomfort, which is temporarily resolved with gastrointestinal cocktails consisting of anesthetic and mucosal coating agents such as viscous lidocaine and sucralfate along with antisecretory medication (Fig. 35.2a, b). These ulcers will often heal with conservative management over the course of several weeks. On rare occasion, recurrent and refractory marginal ulcers require anastomotic revision involving healthier adjacent small bowel and stomach for definitive treatment.

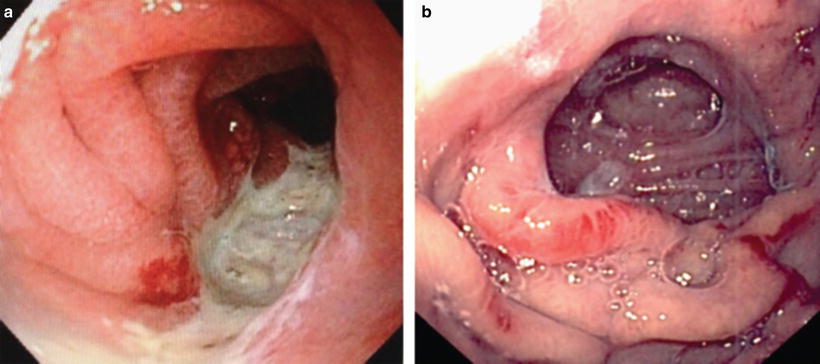

Fig. 35.2

(a) Marginal ulcer. (b) Healed marginal ulcer (Photos courtesy of Kevin Reavis, MD)

Stricture

After gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, progressive food intolerance 3 or more weeks after surgery suggests stenosis of the proximal anastomosis. The reported incidence is 3–12 % and is typically hallmarked by dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting [3]. Endoscopic balloon dilatation with a 12–20 mm balloon is the preferred initial treatment modality, although this can also be achieved via wire-guided bougie dilatation as well. The balloon is inserted 2 cm or less into the stenosis and it is dilated to allow a smaller bore scope with a working channel through the stenosis. When this is achieved, the mid aspect of the balloon is positioned at the stenosis and fully inflated for 60 s. This can be done two or three times during the endoscopy for more effectiveness. If needed, the procedure can be repeated 2 weeks later and serially thereafter. The success rate reported is around 90 %. The presence of a marginal ulcer will complicate dilatory treatment. In this case, medical therapy is most appropriate as long as the anastomosis is patent. Complications associated with balloon dilation are associated with blind insertion. The placement of covered stents has limited value in the treatment of anastomotic stricture, but may be used in select refractory cases [2]. Surgical revision for stenosis is rarely necessary.

Stenosis after sleeve gastrectomy is less common but usually presents acutely. Balloon dilatation and stenting are feasible, with the risk of perforation or stent migration. Conversion of the sleeve to a formal Roux-en-Y gastric bypass serves as definitive treatment in the case of failed repeated endoscopic treatments.

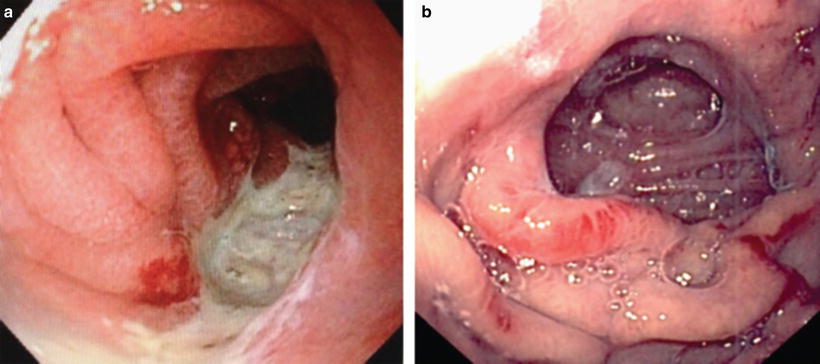

Postoperative Leaks

Although rare, one of the more concerning perioperative complications following gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, and sleeve gastrectomy includes staple line leak. Leaks after gastric bypass and duodenal switch typically occur at the proximal anastomosis. Following sleeve gastrectomy, they most commonly occur along the most proximal staple line near the esophagogastric junction and often present within the first or second week following surgery. The mainstay of the treatment of an anastomotic or staple line leak is source control using wide drainage and distal enteral access for nutrition. The use of fully covered stents to assist with source control and divert enteral flow downstream is gaining favor in that this allows the surrounding tissues to heal and close the leak over the course of 6–8 weeks. Fully covered stent migration is a familiar problem for endoscopists who frequently treat patients with sleeve-related leaks. Although the initial stent is deployed thus covering the leak, distal migration into the sleeved portion of the stomach with the distal landing zone resting against the pylorus results in uncovering of the leak proximally. Deploying an identical stent above and inside the initial stent often results in telescoping of the stents with both resting below the leak. Attempts to secure proximal stents in place with clips and sutures have been marginally successful. The use of partially covered stents results in rapid ingrowth of the esophagogastric mucosa through the stent interstices resulting in significant difficulty in stent removal thereafter. Nesting two different fully covered stents, however, utilizes the structure of each to benefit the combination of the two. Deploying a distal stent with “dumbbell”-shaped proximal and distal landing zones and then deploying a proximal stent (of similar diameter) with simple flared ends allow for the distal flared end to nest within the proximal “dumbbell” of the distal stent, essentially stacking the stents and locking them in place until the leak has healed and proximal removal is indicated (Fig. 35.3).

Fig. 35.3

Nested fully covered stents (Photo courtesy of Kevin Reavis, MD)

In addition to source control and distal feeding to treat leaks, the leak itself can be plugged or closed at the time of initial endoscopy. To augment healing of the tissues involved in the leak, endoscopic coagulation can be used to freshen the involved surfaces, followed by endoscopic suturing, or the placement of fibrin glue, hemoclips, or transmural clips. A French clinical trial is currently enrolling patients with sleeve-based leaks to determine the effectiveness of large transmural clips to reduce the healing time of these leaks.

Band Erosion and Slippage

Although leak following adjustable gastric banding is of minimal concern, the likelihood of band erosion into the stomach after several years becomes a reality in approximately 1 % of patients. Once this is diagnosed, the band is no longer functional and removal is necessary. Endoscopic removal involves cutting the band endoscopically with transoral removal of the band and tubing following abdominal wall disconnection of the port.

For patients who have undergone adjustable gastric banding and present with sudden intolerance to per oral intake, band slippage is a concerning possibility. Endoscopic findings typically include an enlarged gastric pouch with a very narrow or acutely tilted passage into the distal stomach. Mucosa ischemia may be present. This is also easily identified via upper gastrointestinal radiographic studies. Prompt treatment includes surgical repositioning of the band in the correct position on the gastric cardia.

As previously discussed, although some complications following index bariatric surgeries will require immediate surgical revision, many can be approached using definitive transoral flexible endoscopy with or without laparoscopic assistance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree