Figure 12-1 Polymorphic (polymorphous) light eruption. Erythematous confluent papules on sun-exposed skin.

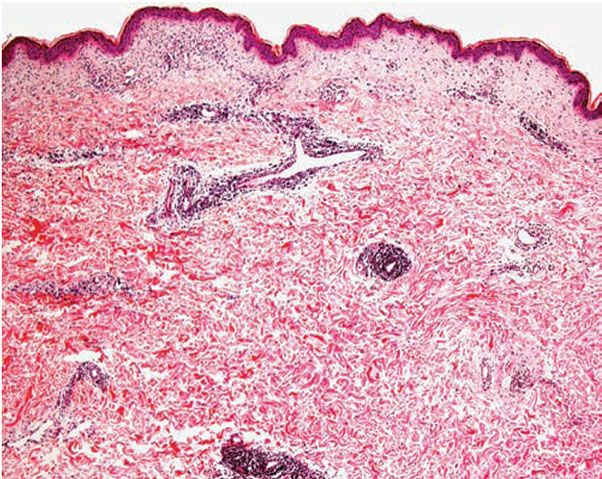

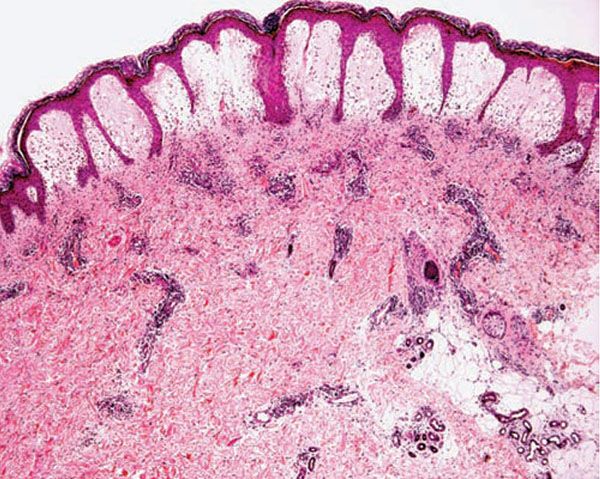

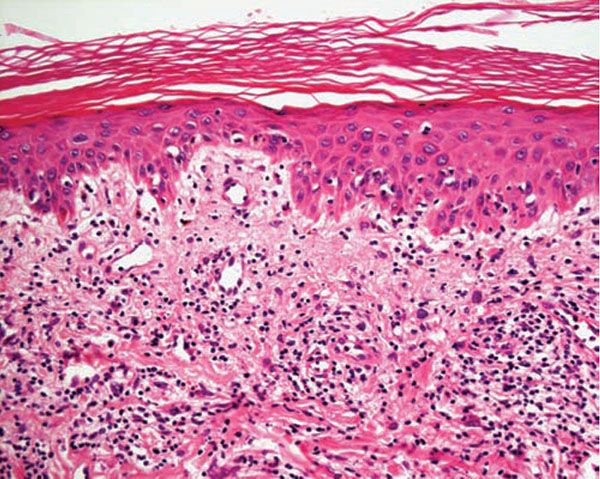

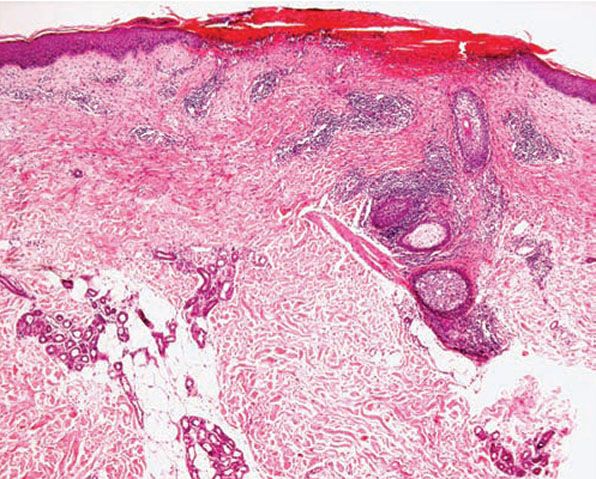

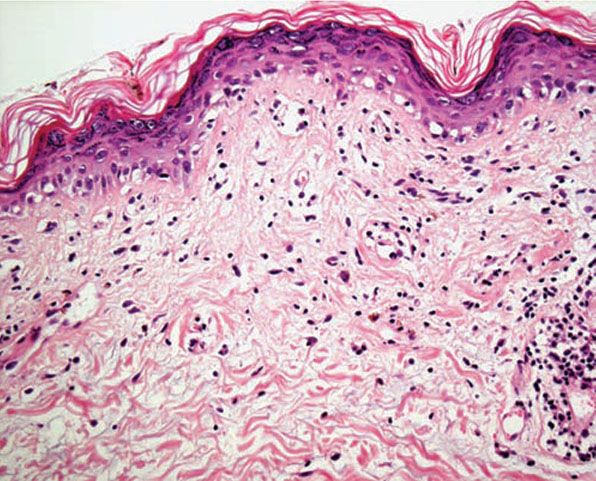

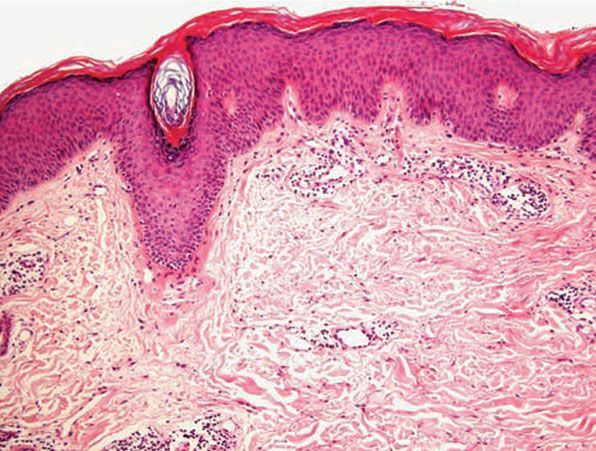

Histology. The histologic findings vary according to the age of the lesion sampled. Very early lesions show either a normal epidermis or mild spongiosis with focal lymphocyte exocytosis and an underlying mild or occasionally moderate, superficial and deep, perivascular and periadnexal, lymphohistiocytic inflammatory cell infiltrate (7–10) (Fig. 12-2); the lymphocytes have a T-helper phenotype (CD3/CD4 positive). Interestingly, in experimentally induced PMLE lesions, the infiltrate in the first 72 hours postinduction also has a predominant T-helper phenotype, but thereafter a mainly T-cytotoxic type (CD3/CD8 positive) (7). Occasional eosinophils and rare neutrophils may also be found. A more prominent neutrophilic infiltrate is exceptional. As lesions progress, there is marked edema of the papillary dermis and more prominent dermal inflammation (Fig. 12-3), along with focal interface change and mild hydropic basal cell degeneration in some biopsies (Fig. 12-4); in such cases, the histologic picture may resemble cutaneous lupus erythematosus (see next section). Exceptionally, a fairly prominent dermal infiltrate may raise the possibility of lymphoma. In a few cases, the histologic findings may be minimal despite the presence of prominent clinical changes (10).

Figure 12-2 Polymorphic (polymorphous) light eruption. Early lesion showing superficial and deep, perivascular and periappendageal, inflammatory infiltrate.

Figure 12-3 Polymorphic (polymorphous) light eruption. Established lesion showing prominent papillary dermal edema as well as moderately prominent, superficial and deep, perivascular and periadnexal, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 12-4 Polymorphic (polymorphous) light eruption. Mild spongiosis and focal interface change with hydropic degeneration of basal cells; the latter may suggest lupus.

Pathogenesis. The eruption of PMLE is induced by exposure to UVR, particularly from strong summer sunlight (2,3). Artificial reproduction is less easy, and exact action spectra have not been conclusively determined. Nevertheless, broadly speaking, the responsible wavelengths appear to be ultraviolet B (UVB) in around half of patients and ultraviolet A (UVA) in three quarters, which includes both in one quarter, while visible light has also rarely been incriminated. The eruption itself appears very likely to be a DTH response in view of its pattern of dermal cellular infiltration, cytokine production, and adhesion molecule expression, arguably to UVR-induced, endogenous, cutaneous autoantigen. Further, it appears that a genetically determined impairment of the normal UVR-induced suppression of induction, but interestingly not elicitation, of DTH reactions in the skin is responsible (11).

Differential Diagnosis. The diagnosis is generally apparent from the clinical history, in which sun exposure is nearly always clearly incriminated as the cause of typical eruption. While not always necessary, if the diagnosis is in doubt, laboratory testing will show that the circulating antinuclear and extractable nuclear antibody titers and urinary, stool, and blood porphyrin concentrations are normal. It may be confused in time course with light-exacerbated eczema but the morphology of the lesions, sites of predilection and histology of the eruption would normally allow distinction. Just histologically, PMLE must be differentiated from lupus erythematosus, the porphyrias, AP, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, chilblains, rosacea, and dermatophyte infections with prominent papillary dermal edema (7,9,12). In cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the interface change is more prominent not only in the epidermis but also in adnexal structures, apoptotic keratinocytes are often seen, and papillary dermal edema is not usually a feature. In addition, dermal mucin deposition may be seen in lupus and is absent in PMLE. A further finding that may aid in the differential diagnosis is that in lupus erythematosus there are numerous CD123 positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells while in PMLE they tend to be absent (13). AP usually displays changes secondary to excoriation, variable epidermal hyperplasia, and more prominent lymphocyte spongiosis and exocytosis; however, early lesions in both conditions may show very similar microscopic findings, except that dermal edema is usually absent in AP. In Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, epidermal changes are absent, there is no papillary dermal edema, and the dermal mononuclear cell infiltrate tends to be more prominent. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is only rarely included in the differential diagnosis of PMLE, mainly when the dermal infiltrate is prominent; however, the exocytosis of lymphocytes with irregular nuclear outlines is not a feature of the latter, which usually also shows variable spongiosis. The histology of chilblains is almost identical to that of PMLE, particularly when there is prominent papillary dermal edema, but fortunately the clinical setting of each disease usually allows distinction. Rosacea shows no epidermal change, dermal edema is absent, the dermal infiltrate is mild and surrounds superficial small blood vessels and adnexal structures, and focal lymphocytic exocytosis into hair follicles is often seen. In dermatophyte infections with prominent papillary dermal edema, a Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain allows identification of the fungal organisms in the stratum corneum.

Principles of Management. Treatment, either prophylactic or remedial, is for the most part effective. Often, the restriction of UVR exposure, use of appropriate clothing, and regular application of high-protection, broad-spectrum sunscreens during exposure are satisfactory preventive therapies for mild disease. In more severe instances, prior to the end of winter, before periods of increased sun exposure, four to six weekly courses of broadband or, more commonly, low-dose narrowband (311 to 312 nm) UVB phototherapy, or slightly more reliably, low-dose psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA), are usually effective in skin immunological tolerance and preventing the eruption of PMLE. If the eruption should develop despite these measures, a short course or several-day course of systemic steroid therapy (20 to 30 mg prednis(ol)one daily) usually abolishes it quickly. Azathioprine and cyclosporine have rarely been used with effect for very severe disease. The value of other previously advocated medications, such as antimalarials and beta-carotene, has not been supported in controlled trials.

ACTINIC PRURIGO

Clinical Summary. AP is an itchy, papular or nodular, excoriated, symmetrical, chronic eruption, usually much worse in summer. It affects the light-exposed and, to a lesser extent, covered skin of children, usually girls, occurring relatively rarely worldwide, although it is comparatively common among native and mixed-race Americans (2,3). It may often, but by no means always, resolve by early adulthood and most often affects the face and distal limbs, while the proximal limbs and forehead beneath the hair fringe, which are less often exposed, are mostly spared. However, the buttocks are sometimes involved through apparent sympathetic immunologic effect spread. Superficial, pitted, or linear scars may affect the face at sites of previous lesions, whereas chronic cheilitis and conjunctivitis, sometime severe, are also possible particularly in native and mixed-race Americans. In addition, some patients describe acute attacks of rash development following specific sunlight exposure similar to the eruption as occurs in PMLE.

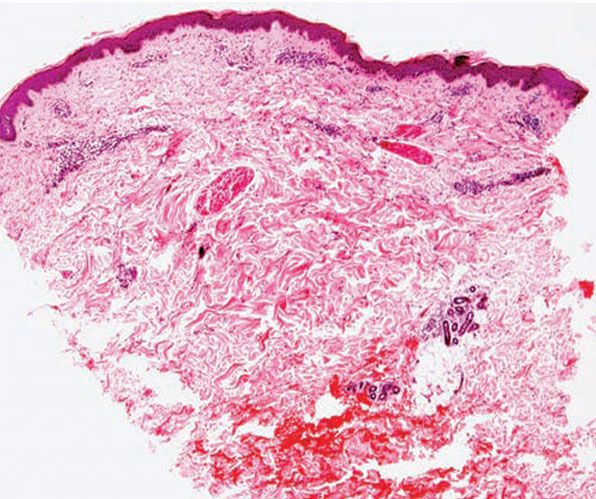

Histology. The histology varies according to the clinical evolution (9). Thus, early intact lesions show variable, often mild, epidermal spongiosis and a superficial and deep dermal, perivascular, mononuclear cell infiltration similar to that of PMLE but in the absence of substantial papillary dermal edema (Fig. 12-5). However, this latter finding may be seen in occasional biopsies, and histologic distinction from PMLE may then be impossible, requiring close clinicopathologic correlation (14). Occasional eosinophils are often seen. The lesions of AP are frequently excoriated, such that careful attention should be paid when biopsy is performed to avoid lesions with such prominent secondary changes (Fig. 12-6). Evolving lesions may also occasionally display focal interface change with hydropic degeneration of basal cells, such that distinction from cutaneous lupus may then be difficult (Fig. 12-7). In rare cases, there may be a heavy, superficial and deep dermal, mononuclear cell infiltrate with difficulty in distinction from lymphoma, especially if associated interface changes are present. In older lesions, there is usually variable lichenification (Fig. 12-8), focal papillary dermal fibrosis, a moderately heavy mononuclear cell infiltrate, and irregular epithelial hyperplasia similar to the features of chronic eczema, or even prurigo nodularis (2,3). The AP inflammatory cell infiltrate has a T-helper phenotype (CD3/CD4 positive). AP must thus be differentiated from the same disorders as PMLE in its more uncommon acute form and from other causes of chronic eczema or prurigo in its chronic forms. Finally, although AP histology may often be fairly nonspecific, the lesions of AP cheilitis characteristically show a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with frequent well-formed lymphoid follicles (15,16), a finding regarded as potentially very helpful in cases of diagnostic doubt. Conjunctival and lip lesions may very rarely display changes that mimic a cutaneous low-grade marginal zone lymphoma.

Figure 12-5 Actinic prurigo. Early lesion with absence of epidermal change, and mild to moderate, superficial and deep, perivascular and periadnexal, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 12-6 Actinic prurigo. Prominent superficial necrosis secondary to excoriation and fairly heavy perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 12-7 Actinic prurigo. Interface change may be more prominent than in PMLE, and histologic distinction from lupus more difficult.

Figure 12-8 Actinic prurigo. Older lesion showing lichenification.

Pathogenesis. UVR exposure appears to be of prime importance in the causation of AP, given the greater severity of the disorder in summer and after sun exposure as well as the relatively frequent abnormal erythemal or papular skin responses to monochromatic irradiation (2,3). Such reactions occur in one half to two thirds of patients, often to UVB wavelengths alone but sometimes also to UVA, while responses to broad-spectrum irradiation have not yet been reported. Further, the clinical behavior of acute attacks of AP, its histologic appearances, its marked familial association with PMLE, and its differentiation from PMLE in large part by the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) subtypes DRB1*04 (DR4) and more specifically DRB1*0407 (2,3,17), all strongly suggest that it is very likely a genetically prolonged form of PMLE. It is therefore most probably also a DTH reaction against UVR-induced, cutaneous autoantigen, but without the isolation so far of proven causative antigen, this statement must remain ultimately speculative.

Differential Diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree