The open brow lift procedure is discussed in terms of relevant surgical anatomy, preoperative evaluation, and detailed surgical technique for pretrichial coronal forehead lift with hair-bearing temporal lift, direct incisional brow lift, and coronal brow lift. Complications are discussed, and information is presented on patient evaluation and expectations, with a discussion of what patients can expect before and after brow lift surgery.

Key points

- •

The vast array of open brow lift techniques provides a durable correction to brow ptosis.

- •

Some open techniques are more powerful than others, with incisions closer to the brow (direct brow lift) offering a greater correction in brow height.

- •

The pretrichial open brow lift is the procedure of choice for brow elevation and treatment of forehead rhytids in patients with a high hairline or long forehead.

- •

With meticulous wound closure and proper patient selection, there is high postprocedure patient acceptance of the incisional scar after pretrichial open brow lift, mid-forehead brow lift, and direct brow lift.

- •

Direct brow lifting rarely results in sensory disturbances, provided that the depth of the excision remains above the frontalis medially.

Introduction

Open brow lifting has been performed for nearly a century and is a widely performed cosmetic procedure today. Open brow lifting encompasses a range of techniques including coronal hair-bearing approaches, frontal pretrichial approaches with or without temporal hair-bearing incisions, temporal hair-bearing approaches for lateral brow ptosis, mid-forehead approaches, and direct brow supraciliary approaches. Combined with small-incisional endoscopic brow elevation, transpalpebral brow elevation, and various forms of browpexy, a palette of options must be considered jointly by the surgeon and patient in determination of the appropriate procedure for each individual patient.

There is an ebb and flow in the approach to treatment of various surgical problems, cosmetic or otherwise. This trend is certainly present in oculoplastics, where today there are, for example, regional differences in the preferred surgical treatment of blepharoptosis. In the strongly consumer-driven markets of cosmetic surgery, these fluctuations can be massive. Some of this fluctuation is media driven, some patient driven, some surgeon driven, and some technology driven. Attaching words like endoscopic or laser-assisted to any procedure generally makes that procedure appealing to patients, as it implies that the procedure is somehow less invasive, less risky, or has less down time. It also implies that the surgeon is current in his or her skills and is at the forefront of the field, whether or not there is any merit to this assumption. How else can one explain laser-assisted blepharoplasty? This phenomenon likely contributed to the wide adoption of endoscopic small-incision brow lifting procedures in the 1990s. Vasconez and Isse first presented the small-incision endoscopic approach to brow lifting in 1992. Initial indications for endoscopic brow lifting were essentially the same as for open techniques, and the requisite small incisions were easily accepted by patients. After an initial upswell in endoscopic brow lifting, the technique is not performed as often today, although clearly in the proper patient with the proper technique, the results can be excellent. The reasons for the shift back to open techniques relate to durability, prevention of hairline elevation (or designed lowering of the hairline), and a desire for less dependence on technology.

Patient evaluation for brow lift

The first branch point in the brow lift decision-making process is determined by the patient’s goals. In the oculoplastic practice, where many patients are referred from general ophthalmologists, often the primary goal of treating brow ptosis and dermatochalasis is to improve vision, with the secondary goal being minimal out-of-pocket expense. In these patients, extended dissection in the region of the frontal branch of the facial nerve makes little sense, so the direct supraciliary brow lift and mid-forehead lift are the only surgeries offered. It is important in this functional population to assess eyelid position while the brow is at rest; it is not uncommon for true blepharoptosis to accompany dermatochalasis and brow ptosis. After performing a brow lift, the central drive to elevate tissue out of the visual axis is reduced, and a true blepharoptosis is unmasked ( Fig. 1 ).

Once the patient has indicated that cosmetic considerations predominate, the evaluation focuses on determining the most effective technique for brow lifting and forehead rhytidectomy that is consistent with the most acceptable risk profile for that particular individual. The clinical examination ( Table 1 ) focuses on the position and stability of the brow, the distance from the top of the brow to the pupil, the length of the forehead, the presence of baldness or anterior hairline thinning, the presence of “widow’s peaks” and other contour irregularities of the hairline, the quality of the forehead skin and depth and prominence of rhytids, heaviness of the tissue about the brow, and the thickness of the brow cilia.

| Hairline | Brow/Forehead | Periocular |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of thinning or male pattern baldness Presence of “widow’s peak” or other contour irregularities | Height of forehead from superior brow border to anterior hairline Quality of forehead skin: thick and sebaceous? Severity of forehead rhytids Thickness of brow cilia | Height of brow from superior cilia to center of the pupil Medial versus lateral brow ptosis Blepharoptosis? Lagophthalmos? Ocular surface disease? |

As a rough guide, it has been suggested that a brow-to-pupil distance of 2.5 cm (measured from the top of the brow cilia; Fig. 2 ) indicates that no further brow lifting be considered. A forehead height of approximately 5 cm (measured at the midline, the distance from the line connecting the top of the brow cilia to the frontal hairline) is considered average, and a forehead length of greater than approximately 6 cm has been used as a criterion in the decision to perform pretrichial open brow procedures instead of endoscopic or coronal procedures. For some surgeons, including the senior author, the pretrichial and coronal hair-bearing open approaches are the procedures of choice, with the pretrichial procedures far outweighing the coronal procedures in frequency. Occasionally a combined pretrichial and hair-bearing approach is indicated to reduce hairline contour abnormalities. In these instances, the path of the incision can span hair-bearing and pretrichial scalp to even out hairline irregularities such as the widow’s peak.

The brow configuration is a central consideration. In younger patients, early lateral hooding can be addressed with an isolated hair-bearing temporal lift. In these patients, it may not even be necessary to disrupt the temporal fusion line with this procedure. The temporal brow and lateral canthal region also need to be considered in the context of the other procedures that the surgeon is going to perform. For example, if a midface lift is part of the operative prescription, a temporal lift is often required to redistribute the excess tissue that normally would accumulate at the superolateral leading edge of the midface lift.

The ophthalmic history and physical examination focuses on the presence or absence of lagophthalmos, lid position at rest, and ocular surface disorders including dry-eye disorder. A history of refractive procedures, some of which can lead to temporary denervation of portions of cornea, is noted. If warranted, a slit-lamp examination of the ocular surface is performed. As noted earlier, subconscious brow elevation is often part of a compensatory mechanism for blepharoptosis. Therefore, eyelid position with the brow at rest must be documented, and an appropriate ptosis repair procedure may need to be included in the operative plan.

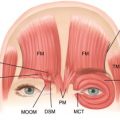

Surgical anatomy

The anatomy relevant to forehead lifting has been well described, particularly with respect to the facial nerve and supraorbital bundle. The most feared complication of brow lifting remains palsy of the temporal branch of the facial nerve. Above the zygomatic arch, the branch lies along the deep aspect of superficial temporal fascia (superficial to the deep temporal fascia). As dissection moves inferiorly, deep temporal fascia proper splits into two layers:

- 1.

Intermediate temporal fascia, inserting on the anterior aspect of the arch

- 2.

Deep temporal fascia, inserting on the posterior aspect of the arch

Dissection remains along the intermediate deep temporal fascia to avoid injury to the overlying temporal branch. As is widely appreciated, the temporal branch runs in a supermedial direction approximately 1 fingerbreadth above the lateral aspect of the brow.

The sentinel vein, where it perforates the temporalis fascia, is in close proximity to the temporal branch of the facial nerve. It passes from the subcutaneous plane through superficial temporalis fascia and then through the deep temporalis fascia, at the outer aspect of the superolateral orbital rim, near the tail of the nonptotic brow. Exercising the standard cautions during dissection in this region is prudent:

- 1.

Remain along the deep temporal fascia proper.

- 2.

Avoid aggressive flap elevation near the tail of the brow to avoid tractional injury to the facial nerve.

- 3.

Penetrate the temporal line of fusion from lateral to medial to avoid inadvertently choosing a plane that is too superficial, placing the nerve at risk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree